The belief that with the right instruction manual and enough grit and determination we can all become smarter, hotter, richer, more likeable versions of ourselves — or better yet, completely different people entirely — is nothing new. It fuels the multi-billion-dollar self-help industry. The dangling carrot of an elusive best self, always just around the corner but perpetually out of reach, compels us to read books with alluringly delusional titles such as The 4-Hour Workweek and Breaking the Habit of Being Yourself.

In recent years, the self-help industry has been dominated less by calls for ruthless, shameless striving, and more by softer but equally grating assertions that to achieve true salvation, we must all learn to love and accept ourselves, warts and all. And yet, given the opportunity, most people would trade their flawed, existing self in for an undeniably improved model in a heartbeat. While, as of yet, there is no shop where you can buy a better you, what if all it took to go from NPC to MVP was to disappear for a month?

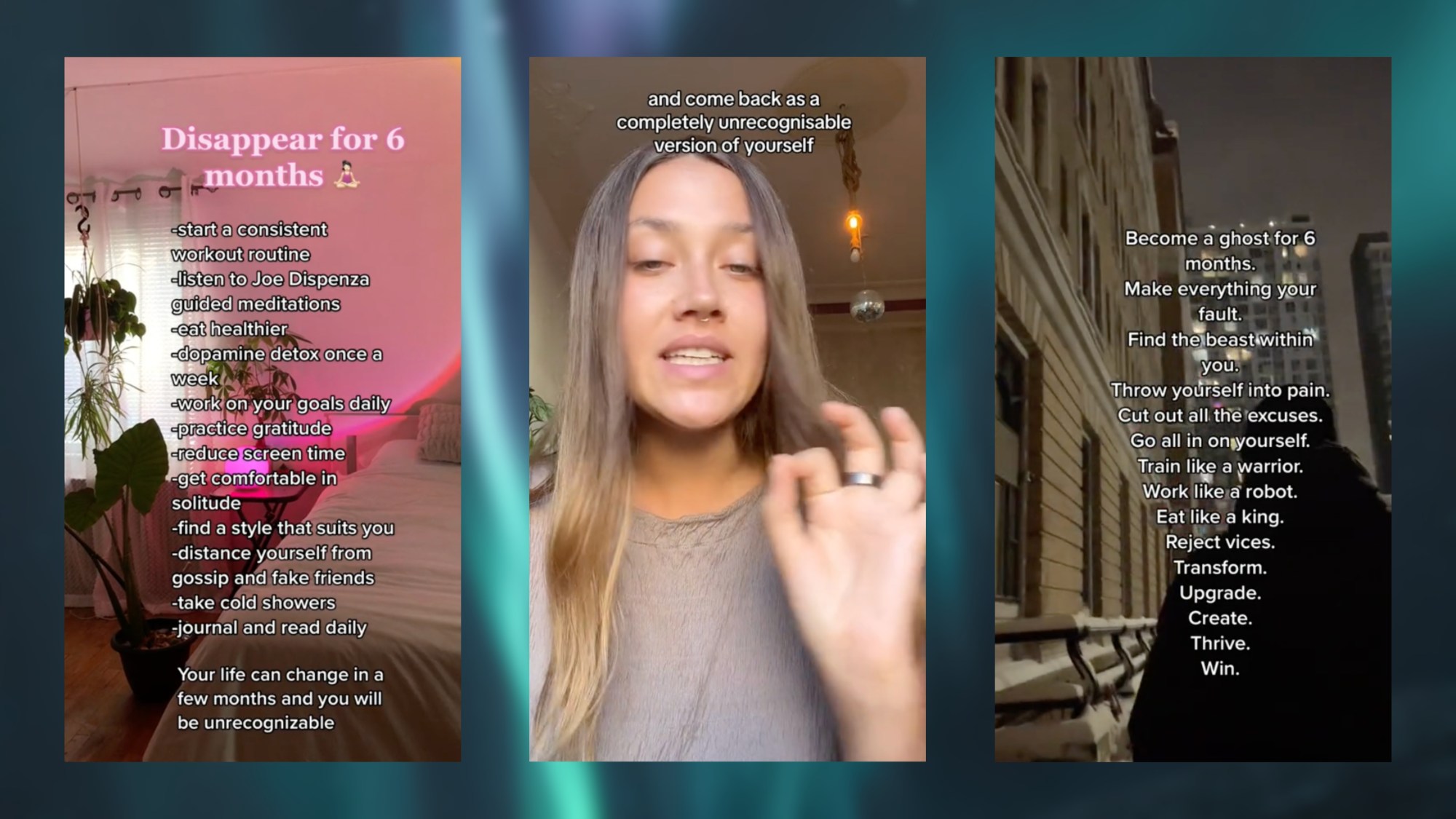

On TikTok, manifestation girls and body boys are imploring their followers to “disappear” for one to six months and “come back completely unrecognisable” to “shock them all”. Their advice on how to emerge, butterfly-like from the chrysalis, ranges from the seemingly sensible (exercise, go offline, stop drinking alcohol, avoid toxic people) to dubious (swap tap for remineralised water, make everything your fault, make yourself scarce to become more valuable, practice “semen retention” to attract women) and hilariously vague (start a scalable business). Disappearing women showcase their journeys through pastel tones, manicured hands clutching journals, ample butts bouncing on treadmills, and millennial interiors, while their masc counterparts rise in the darkness to wash their faces in the sink, pound the pavement and lift weights in solitude. Many videos are soundtracked by a voiceover directive to “go to war against the girl/man in the mirror and don’t come back until you win”.

To simply “disappear” in the face of adversity recalls the listless, pill-popping narrator of Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation, or a fake-your-own-death-with-the-aid-of-supermarket-hair-dye scenario a la Gone Girl. However, in the self-help lexicon of 2023, to disappear suggests a rebrand more in line with Reputation-era Taylor Swift, who in 2017 famously went dark amid a feud with Kanye West and Kim Kardashian, only to reappear with a new, cunty disposition, crooning “Nobody’s heard from me in months / I’m doing better than I ever was.” Less psychotic break, more triumphant return to show the haters who you really are.

Dr. Riki Thompson is an associate professor of writing studies and digital rhetoric at the University of Washington Tacoma who specialises in communication and connection online, with a focus on mental health and self-improvement. She sees the disappear trend as the next iteration of reality TV transformation shows such as The Biggest Loser, Extreme Makeover, What Not To Wear and Queer Eye for the Straight Guy. “In these shows, the hosts come in and do an extreme makeover on a person’s wardrobe, hair and makeup, and then there’s a big reveal and everybody’s like, ‘Oh god, I don’t even recognise you!’” says Dr. Thompson. “Extreme transformation is the indicator of success… Now, TikTok has become the new reality show where there’s that big reveal.”

Some groups have been disappearing long before it was a trend. People with substance abuse issues go to rehab to physically and emotionally heal outside of their normal environment, with a view to eventually reentering society and implementing what they learned in isolation. Within Buddhism, group or solo retreats are commonplace, and can span anything from a few days to literal years and include meditation, chanting, sobriety, clean-eating, fasting, celibacy, and silence.

Tenzin Tsapel, a Buddhist nun living in Bendigo, Australia, did her first retreat in Dharamshala, India, in 1982. “Three months seemed so long to me then,” she recalls. “It was with a group and it was hard work, but we achieved an incredible stillness meditating together. It was a temporary way of seeing what is possible with the mind. Afterwards, I noticed a huge change in my mental relaxation, openness and appreciation.” Three years later, she was ordained as a nun by the Dalai Lama.

While a monastic life is not for the fainthearted, Tsapel believes that anyone can benefit from a disappearance of sorts. “If you never try withdrawing from habits that have increased over time, you never know how they’re affecting you,” she says. “The more we can learn, examine and just experience who we are, who we want to be and how we are going with that, as well as our dark sides, is so valuable… I don’t see a problem with a solitary, isolated way of doing that.”

During the pandemic, Hali Christou was living alone and processing the death of her cousin, when she cut herself off from “virtually everyone” and went hard on exercise and self-help. “I started therapy, read lots of classic, trendy self-help books — Marianne Williamson, Louise Hay, The Body Keeps the Score, and that stupid attachment theory one — and got really into astrology tarot readings on YouTube for constant, droning reassurance,” she explains. After her work as a fashion stylist stalled due to lockdowns, she started “a really shit tote bag store on Etsy”, which eventually led to more fulfilling work and a move to Paris to work for a large fashion house. While Christou has since reappeared, so to speak, that period of intense isolation gave her the space to start a post-production and design business that has provided new financial and creative freedom.

For others, a period of downtime is empowering, but not life-changing. “This September, I did a full-on cleanse,” says Julianne, who lives in New York and works in the music industry. “I had just turned 30, was feeling super gross, and wanted to prove to myself that I could do it. I have addiction issues on both sides of my family and kept telling myself I was going to take a break from weed and make all these changes. I finally did everything at once — no weed, alcohol, Instagram, gluten or cow dairy.” While for Julianne, it felt good to abstain and remind herself that most of her “vices” are more about the ritual than the substance, she’s mainly resumed her old habits. “I don’t need this stuff, but I end up doing it anyway, because I’m a hedonist!”

Since quitting drinking, Instagram and unfulfilling socialising, New York-based creative director Lauren spends more time “being moisturised, hydrated and in my lane” and less time on things she previously felt obliged to do to qualify as an active participant in the world, such as going to the pub or to gigs. “I always felt like I was on a hamster wheel that I couldn’t get off,” she recalls. While she loves her new, more intentional life, it can be lonely: “When I’m consuming media — like Sex and the City — that’s really dominated by themes of female friendship and community, sometimes I worry that I’m not fulfilled in that respect.”

While the disappear trend draws from more established isolation frameworks such as rehab and religious retreats, those experiences exist within a supportive, structured community of people with shared goals. In contrast, disappearance advocates emphasise the need to ghost and show no signs of life and position isolation as imperative to success, with friends and community just a trifling impediment to self-actualisation. Their messaging largely fails to acknowledge that whatever toxic relationships are severed must eventually be replaced with something more nourishing. When these content creators do mention other people, it’s to remind potential disappearers that all this rising and grinding will ultimately leave an unnamed audience speechless at how far they’ve come. While success may be the best revenge, the desire to prove one’s perceived detractors and doubters wrong is not the most noble or sustainable basis for personal transformation.

Even so, drastic action can be both thrilling and necessary and is undoubtedly more entertaining than a slow and steady march towards betterment. There’s a reason that reality TV transformation shows and their promise of radical metamorphosis are so compelling: no one is above a good makeover. Perhaps there’s a psychic solution that lies somewhere between touchy-feely, saccharine notions of radical self-acceptance and the aggressive desire to metaphorically murder your life and come back a completely different, nebulously improved person. While we might all dream of disappearing sometimes, to do so would rob us of the hard but rewarding task of figuring out how to bearably exist in the world as our enduring, fundamental selves.