August, 1989. The National Union Of Students, still a politically radical organisation railing against the Thatcher government, is trying to get young people to campaign the abolition University maintenance grants. They put an advert in the NME with the headline “STUDENT LOANS – HOW WILL IT AFFECT YOU?” It reads:

“Last November the Government announced that it intended to put an end to the system of student financial support and introduce student loans. The proposals will mean that from 1990 students will face a debt of £420 per year.”

How quaint that now sounds. Most graduates today leave with a total debt of £44,000. By the time it’s paid back, the debt will have risen to around £65,000. Some estimates suggest 85% of people will never pay back their student debt. Most of us are prepared to rack up such a massive IOU because we believe the high cost of university is an investment: graduates receive better paid jobs than non-graduates. Fine, if you want to be a vet or a lawyer, but what about if you want a job in the creative industries?

Almost half of graduates under 30 are working in non-graduate jobs in areas like catering or hospitality, and the highest number of these are graduates with a degree in the arts, humanities or media. These subjects also have the highest rate of unemployment and the lowest average wage.

When jobs in the creative industries do become available candidates often have to compete into what one LSE report called “tournaments for entry” – multi-round interviews, essays and activities that can take months to complete and have very little relation to their degree.

Do you need a three year English lit degree and a feminist-marxist reading of Simone de Beauvoir if you want to be an A&R for a record label, or just a decent taste in music and the number of a dealer who delivers?

Is it any wonder then, that many are questioning whether a degree is such a good idea. Do you have to pay to go on a menswear course to be a menswear designer? Or would your time be better spent interning and learning on the job? Do you need a three year English lit degree and a feminist-marxist reading of Simone de Beauvoir if you want to be an A&R for a record label, or just a decent taste in music and the number of a dealer who delivers?

Creative jobs need skills, of course they do. The question is whether you’d be better equipped learning those skills at a university or whether you’d be better learning on the job. Sure, lots of creative courses offer work experience, but that’s not the same as getting dropped in the deep end on the job and learning on the job.

Babak Ganjel spent four years studying art at St. Martins. He loved the degree, but, since graduating almost a decade ago, has struggled to find work. “Every time I hit rock bottom I wish I had just gotten a job instead of going to university,” he says. “But I don’t regret the benefits and freedom experienced at Art School, as it allows me to contextualise every stupid job I say yes too. I don’t fear doing any shitty small time jobs I have to do to pay the rent, your creative brain works much better when it isn’t chasing money.”

Colin Roberts went the other route, moving to London after secondary school he got a job on the London Underground, working on ticket barriers. He did some freelance writing on the side and eventually got a job editing the music website Drowned In Sound. He’s now 28 and works at Big Life Management, co-managing London Grammar and Chloe Howl. Does he see any point in getting a degree if you want to work in music?

“If you’re not doing something specialist within music (skilled/technical jobs like sound engineering or accounting) then no. The best way of getting in is just doing that – getting in. I got lucky, I’m co-managing artists with people who took me under their wings years ago and taught me a great deal about the industry. I’m 99% sure that the key points I’ve picked up from doing my job could have never been taught in a university. The main thing I guess I missed out on from doing a three year stint at a uni was the partying and ‘growing up’, but I’d argue that nothing matures you more than being thrust into the middle of London on shit salary and having to deal with everything that comes along with it.”

If university teaches you anything it’s that two people’s personal experiences doesn’t make for any bold conclusions. And of course, getting a job in the creative industries, even a shitty, low-paid, tea-making, laundry-doing, boss brown-nosing job is getting harder all the time, whether you went to uni or not. But it does seem that if a creative job is your goal, going to university might not be the right way to go about it. In fact one fashion lecturer I spoke to thinks that certain types of creative degree are ripping students off. She asked not to be named for fear of being fired, but says she feels sorry for thousands of students taking masters degrees in the hope of getting a job in the creative industries. “In the last few years, universities have had to widen their intake for masters degrees because the amount they can get for undergraduate courses has been capped. This means that people who are not equipped for master level study – whose English isn’t great or aren’t especially passionate for the field – are being let on to courses in huge numbers. At the same time I have hundreds of students on my BA course and it’s just not realistic that most of them will get jobs when they leave, even if they work hard and get firsts. Most will have to intern for up to two years after graduating to stand a chance. If they heard the way some of their lecturers talk about their prospects behind their backs, they’d feel lied to. Universities are offering these courses to make money, but there is no other product which you could charge £27,000 for with no guarantee of the thing you’re basically selling – employability.”

Not Going To Uni is an organisation that have been making the case that a degree might not be necessary for years. Sarah Clover, who helps run the organisation, working with young people to discuss their future, says she’s seeing a shift in the cultural value given to a university degree.

“We have a stand at career fairs, and a few years ago parents would be dragging their kids away if they came over to talk to us. Now it’s the opposite, parents want their kids to see the benefits of apprenticeships and other training. You can get apprenticeships right now at Sky television, in theatres. One major label offered an A&R apprenticeship. Instead of studying for a degree that might not help you and getting into huge debt, you can get paid to learn on the job and gain the experience you need to get employed.”

So with mounting debts, no guarantee of a job, poor courses and a number of better routes available. Is there any point of getting a degree if you want to work in the creative industries?

I think so.

If you want to work a job in the creative industries, which – let’s be honest – is a job where you can follow your interests and personal ambitions and, if it all goes well, where you’ll get to see the world on someone else’s expense card, meet the people you admire and sleep with a more attractive class of people, then you should pay your dues for what is basically a self-interested life choice.

Doing a course in media studies might be a waste of time if you want to work at the BBC, but doing a course in history or biology or politics or engineering or even media studies – if it is truly the study of the media that interests you – is valuable in and of itself. There is a line in Zadie Smith’s novel The Autograph Man, “I saw the best minds of my generation accept jobs on the fringes of the entertainment industry.” This is stingingly true. Too often brilliant people spend too long PRing no-hope indie bands, fetching the lunch of a once-successful visual artist, buying props for a reality TV show.

These people have not made the bad choices, some of them will end up having lives that are more glamorous and more exciting than any civil servant or scientist. But even if they make a success of themselves, we can’t pretend that a job in the creative industries is the same as a job in the UN. We try of course, with awards and Twitter back-patting, making it seem like culture is all there is. But it isn’t, and studying alongside people who haven’t got a clue who Henry Holland is one helpful way to remind us of that.

University is not the only place you can learn about the world, and there are plenty of hyper-intelligent and wildly knowledgeable people that left school at 16. But University is the one point in your adult life where you can receive some shelter from the economic and social imperative to earn money so that you can live. Yes, you end up paying for it down the line, and your student loan isn’t enough to cover basic living costs so you’ll have to get a weekend job, but for a few years you are still afforded the opportunity to do something that doesn’t necessarily have any bearing on your future ability to support yourself.

Not everyone can afford to go university in Britain. As a result of the socially regressive privatisation of higher education that’s taken place since that NUS advert was printed, there are many people that can’t afford a three year journey of academic realisation in a subject that might not help them find work. That is something that some people outside the creative industries are fighting hard to change. But if you are one of the lucky ones that has the privilege to be isolated, for a few years at least, from economic pressures and endeavour to do something for the sake of it – whether that be study, protest, netball or drinking – then you should. You won’t have another opportunity for the next 50 years to do so, and when you do enter the world of work you’ll likely be richer for it.

The main thing university taught me was that I know nothing about anything.

The main thing university taught me was that I know nothing about anything. That any subject I may have thought I had the most basic handle was infinitely more complex, an infinitely more multi-faceted than my shamefully pickled brain could ever understood. As an undergraduate, I was at the bottom of a centuries old ladder of understanding, and almost every accepted explanation of what is true has been challenged and rethought a thousand times.

A staffer at Buzzfeed hilariously claimed the other day that listicles can be an important as investigative, high-quality journalism or study and there’s not necessarily “a direct correlation between word count and quality, and word count and impact” . Anyone who has read hundreds of books for a dissertation and still felt like they don’t understand anything knows that this is not the case.

But it also gave me the tools to acquire knowledge. When there is a paradox or phenomenon I need to understand, I feel like I can find the right things to read and the right people to speak to, how I can approach their perspectives critically and then realise I was asking the wrong question and start all over again.

The kicker is of course that a degree, whether artistic or not, always ends up influencing your creative work. Art, fashion and film are the much richer for a deeper understanding of their context and influence. The most iconic fashion innovations of the 20th century came not from designers but from the world outside: the modern bikini was invented by a car engineer, the iconic style of Vivienne Westwood came from street punks re-appropriation of everyday objects.

You don’t need a degree to work in the creative industries. but the creative industries do need people with degrees, people who want to challenge structures, that want to use depth of knowledge to create complex and spectacular art and find a way to make culture more responsive to the bristles of the real world.

Credits

Text Sam Wolfson

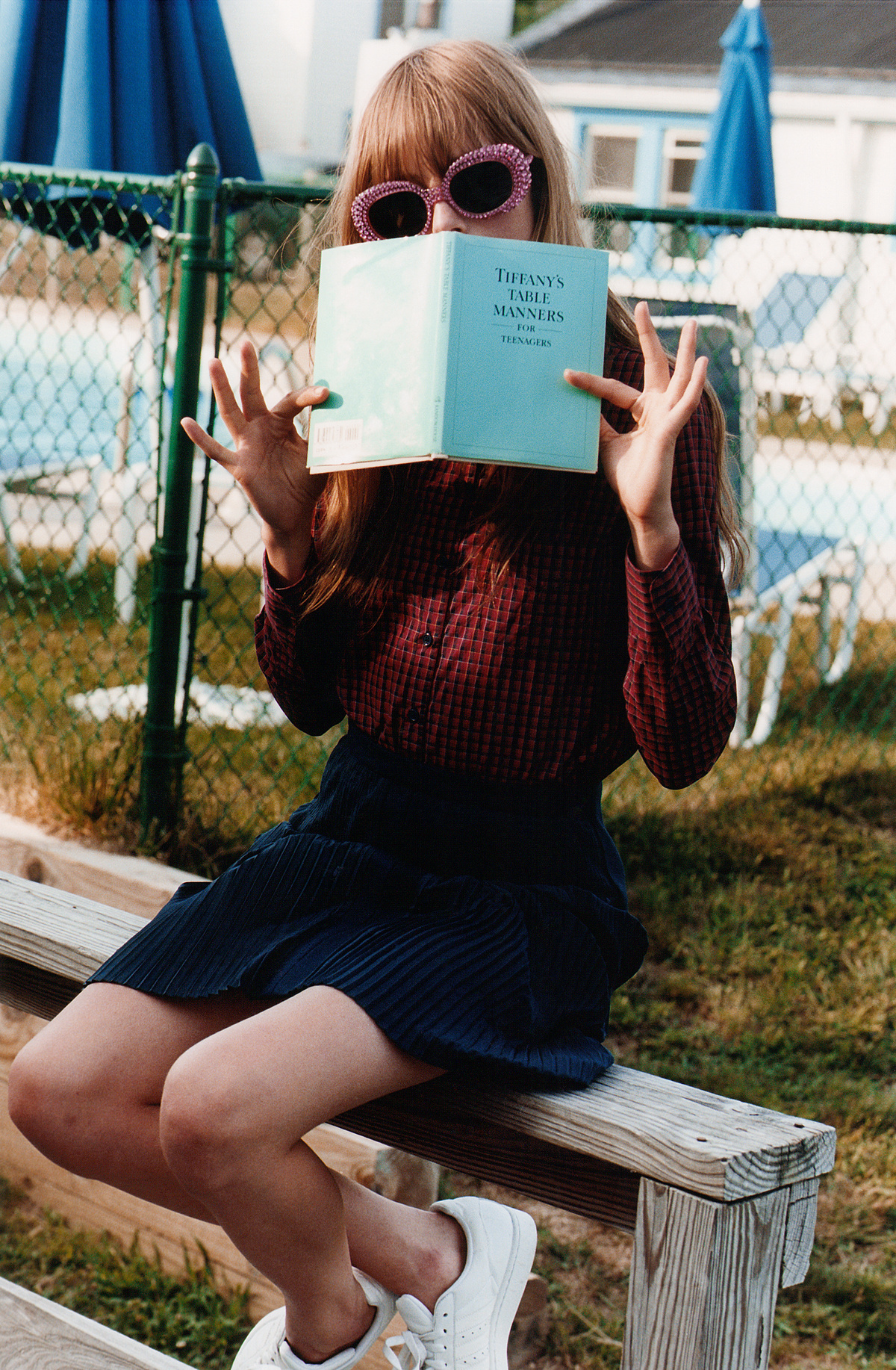

Photography Matt Jones