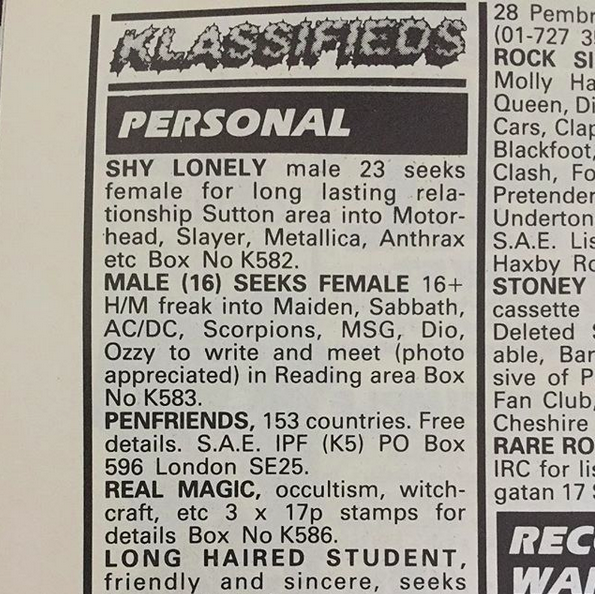

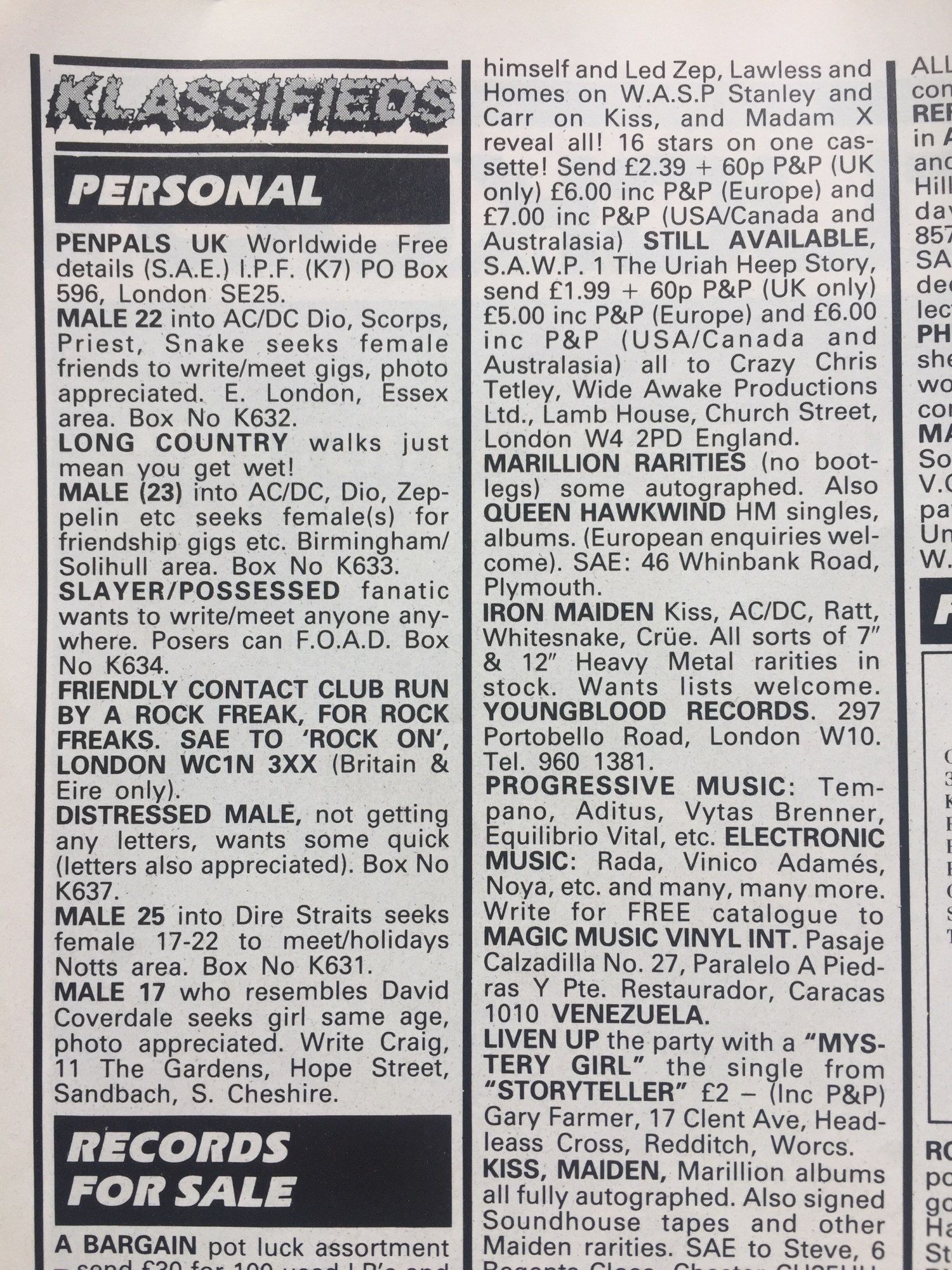

“Male 17, who resembles David Coverdale seeks girl same age, photo appreciated,” reads one ad in the classified section of an old metal mag. Then there’s a Whitesnake fan looking for “female friends to write/meet gigs” in east London and Essex, while a Scorpions and Mötley Crüe fan in Edinburgh looks for “penfriends” outside of Britain. A touching insight into what it was like to be a fan in the 80s — with classifieds and lonely hearts columns once a vital source of companionship for a lonely metal kid in a small town. They have feelings too, you know.

Justin Quirk, a former music journalist and now author and curator, has been pouring over old metal magazines and archives, researching for his new book, Nothing but a Good Time. It charts the rise, fall — and the outrageous stuff in between — of glam metal. Starting in 83 (with bands like Mötley Crüe and Shout at the Devil) and ending in 91 — when Guns N’ Roses’ Use Your Illusion and Nirvana’s Nevermind came out within weeks of each other — Justin will explore glam metal one year per chapter, taking in groups like Dokken, Skid Row, Van Halen, Guns N’ Roses, Def Leppard, Warrant, Cinderella, Vixen, LA Guns, Poison and WASP. Justin has managed to track down peripheral figures, obsessive fans from the time, people who were in the crowd in 88 during the fatal crush at a Guns N’ Roses set, and the designer who drew the cover of Def Leppard’s Hysteria.

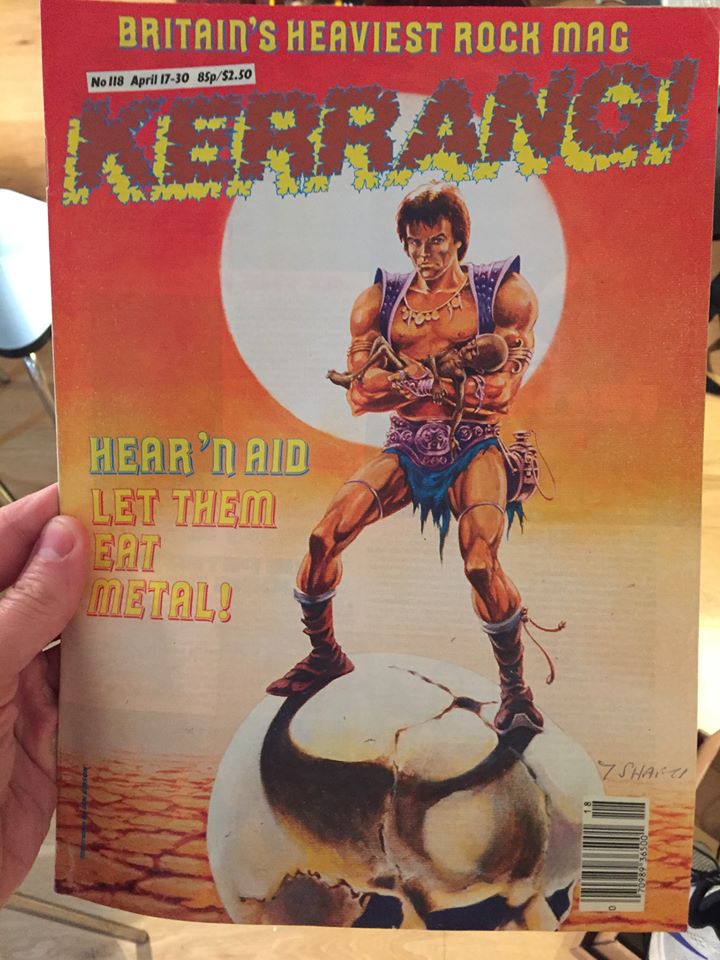

“It was such a weird genre — an enormous spectacle — that in some ways it functioned as the musical wing of the whole rebirth of America through that decade,” Justin says. “Reagan, the big bang, the defeat of communism… before turning in on itself and becoming something much darker.” It was a weird genre that Justin himself was pretty immersed in as a kid in the late 80s and early 90s. “I used to go to a lot of gigs, read stuff like Kerrang! and Metal Hammer every week, listen to the few metal radio shows there were, and I worked in guitar shops.” So plenty of the research for the book was done back then, but he’s also been using memoirs and autobiographies (Seb Hunter’s Hell Bent For Leather for the fan perspective, for example, and Slash’s book from the celebrity standpoint), as well as old back issues of Kerrang! and the US mag Circus.

Specialist magazines were a treasure trove of information for fans wanting to order zines and join fanclubs. In a world before smartphones and map apps, record stores would even include directions to their doors, to help wannabe crate diggers find their way to the shop.

“It’s like a really strange time capsule of the world before the internet,” says Justin. “People who run bands’ fan clubs in Europe placing adverts to find out if there’s a UK fan club, and if someone can put them in touch; people looking for one particular record. Then there’s the personal classified ads — all of them seem to be from people who are the only metaller in their little town, and are desperate to meet a girlfriend, or a pen pal, or even just anyone who’s into the same sort of stuff as them.” He’s unearthing individual stories too, like the man he found via an old festivals site who was in the crowd at the Monsters of Rock festival in 88: “Guns N’ Roses had just become huge but were still very low down the bill, which contributed to a huge crush in the crowd. The weather was awful, and a number of kids were trampled to death as they played. It was an awful event. It’s been kind of forgotten about, but it led to a lot of changes in the way that those big outdoor gigs were organised. This guy wrote an account of it online, as he lost one of his friends that day. I’m interested in telling this story from the ground, rather than the more well-trodden superstar angle, so people who lived through those kind of moments are a great source.” Justin is interested in why the genre that spawned such dedicated fans essentially came to an abrupt end in 1991. People often cite the rise of grunge — as well as the emergence more music-driven metal bands such as Guns N’ Roses — but he says it might have been destined to happen anyway, and fits into a wider musical context. “Taking a longer view, I think the whole glam scene was a kind of end point of an entire era of white American guitar music,” he says. “It used elements from different styles of the previous 40 years — cowboy music, blues, glam, punk, musicals — and crushed them all together without context.”

“What really interests me is the increasing pace that the genre gathered in those last years leading up to 91 — it was a strange time in American culture: the economy was rebuilding after the recessions of the late 70s and early 80s, everything was deregulating and becoming bigger, more shocking, more inflated (art, advertising, action films). It was like the whole culture was on steroids, and glam metal was the musical arm of this — but like all artificial highs, eventually there’s a crash.” Michael Hann, freelance music writer and former music editor of The Guardian, agrees with the “artificial” analysis of glam metal. “For me, it is one of those genres that took something great — in this case Van Halen, one of the most important bands ever — but amplified all the cheap and nasty bits of it, and without the same finesse and humour that the originators had.”

That’s not to say he dismisses its impact though, on both fans and the music industry: “What’s interesting about glam metal though, is how long and significant its reign was. It tends to be regarded as an aberration, but if so, it was a hell of a long aberration — basically, the whole of the 80s. For most of that decade, if you were a rock band and you wanted to make an impact in America you had to dress up in the clothes of glam metal. And they did. Everyone did. The exemplar of that is David Coverdale sacking all his old blues blokes from Whitesnake and getting in the tousled young guys for the 87 line-up. You had to go glam. If you look at a Billboard album chart from the mid-to-late 80s, you’ll see scores of albums that even if not definitively glam, are by bands who’ve taken on some of the trappings.” This ubiquity was part of the genre’s demise: episode 5 of documentary series Metal Evolution shows how glam metal sort of ate itself by the end of the decade, with the LA scene reaching ridiculous levels of excess, bands were encouraged to release power ballad after power ballad, and label executives flooded the market with identikit hair-metal boy bands. For Michael, the music itself was also part of the problem (more so than the rise of grunge) and why the genre isn’t taken seriously today. “Because it wasn’t serious. I mean, who’s going to write a lyrical exegesis on Animal (Fuck Like a Beast)?” he says. “Second, because it was mostly rubbish. In large part, at least. I mean, it really was. There are plenty of fun glam metal singles — and lots of amazing stories, which is why people still like writing and reading about it — but there’s not a lot to really cling onto there. It was so formulaic, so unreal, that I completely understand why no critics were going to bat for it.” “It was not a genre built for longevity: there just isn’t much development you can make from the template those bands adopted, and they were so purposefully shallow that when they did try to evolve no one believed them. Nevertheless, the shallowness and silliness made them perfect for the rehabilitation of nostalgia, which is why I think so many of those bands became big draws again.” And there are still many, many fans out there, and plenty of them are too young to have been glam metal heads the first time round. Srdjan Bilić, in his 20s, plays guitar in the house band at Shot Through the Heart — a regular glam metal and hard rock party in London, as well as in a heavy metal band called Primitai, influenced by acts like Iron Maiden, AC/DC, Kiss, Mötley Crüe, Saxon, and Judas Priest.

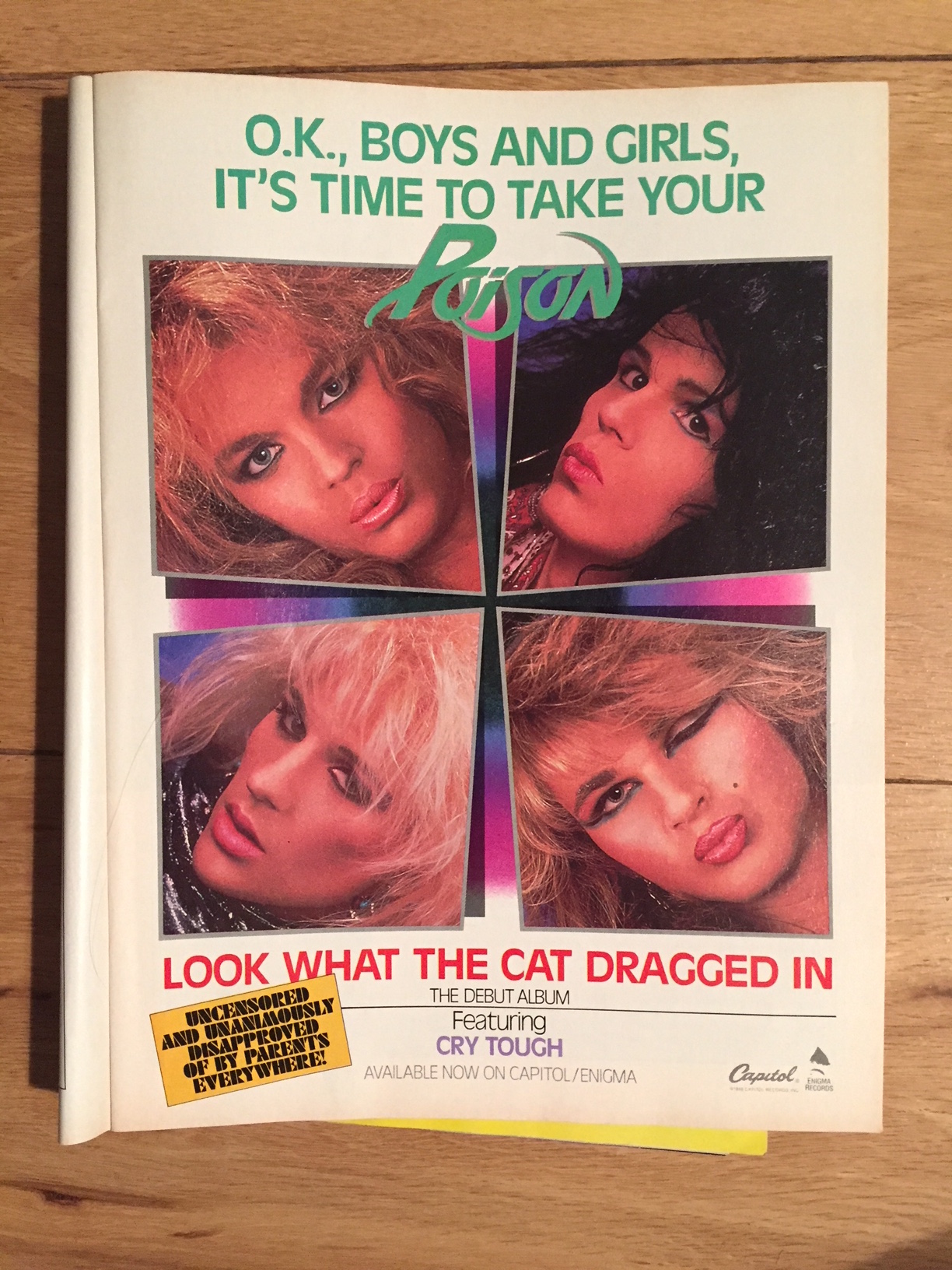

For Srdjan there’s something about the community around glam metal that draws him in. He says there’s a positive energy to it, and an unapologetic approach to just partying to music you love: “The fact that the music is to be enjoyed and have a good time to. That’s what glam metal is. At any gig or gathering with that music, people are having a great time and socialising.” Carrie King is another all-out fan, namely of Mötley Crüe, Poison, Skid Row, Def Leppard, Kiss, Guns N’ Roses, Van Halen, Ratt and Whitesnake, as well as Thunder and Twisted Sister. “I just love the whole craziness of it all. I don’t know if it was ever meant to be taken seriously, but as a fan I’ve always seen it as quite a light-hearted type of music, in contrast to a lot of the serious, straight-faced stuff that was around at the time.” Despite being accused of being shallow, glam metal was also pretty subversive, with men in spandex and a lot of permed hair, “I love the fashion, love the fact that the frontmen were so confident in both their stage presence and their fashion. Men wearing make-up! And tighter trousers than the women! Brilliant! I love the guitars, huge amps and self-indulgent drum solos. I find it funny that there is snobbery. You show me one person who doesn’t sing their heart out when Livin’ on a Prayer comes on during a night out!”

One of the major characteristics of glam metal, and what makes many wary of it, is the genuine don’t-give-a-shit attitude, in a world of irritatingly earnest or smugly ironic music scenes. As Justin says, there is a “s total lack of irony” with glam metal. “From grunge onwards, music is very self-referential, but glam metal — while aware of how ludicrous it could be — was quite straightforward and un-ironic. I think that kind of sincerity is what makes people feel distanced from it as much as anything musical or stylistic.” Not that many hair metalheads are particularly bothered about in-depth analyses like this: they’re just here for a good time.

Nothing but a Good Time will be published later in the year. To help this happen and pledge to the project go to unbound.com/books/good-time where you’ll also find more information and the film trailer.