Late one night in August 2013 in a park in the centre of Kiev, a 20-year-old Ukrainian named Dimitri gave Brooklyn-based photographer Dan King a stick-and-poke tattoo by the light of an iPhone. Looking at it now, you can just about tell it’s a wombat, but it helps if you imagine you’re halfway through a bottle of Soviet-proof vodka.

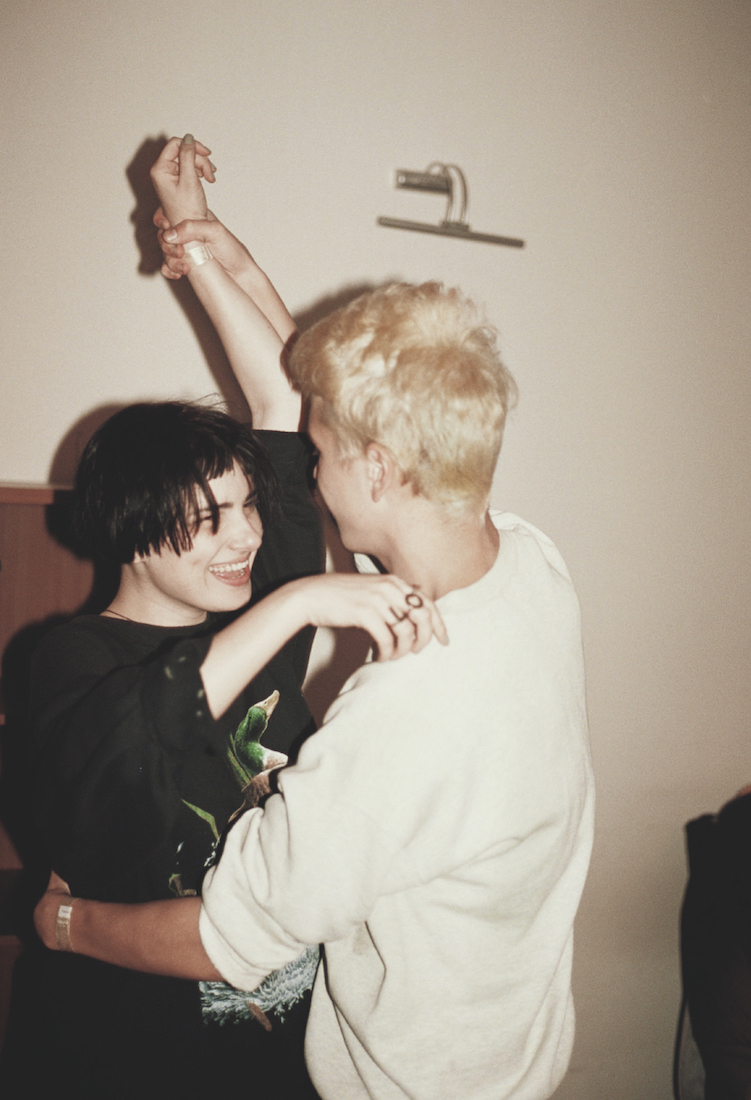

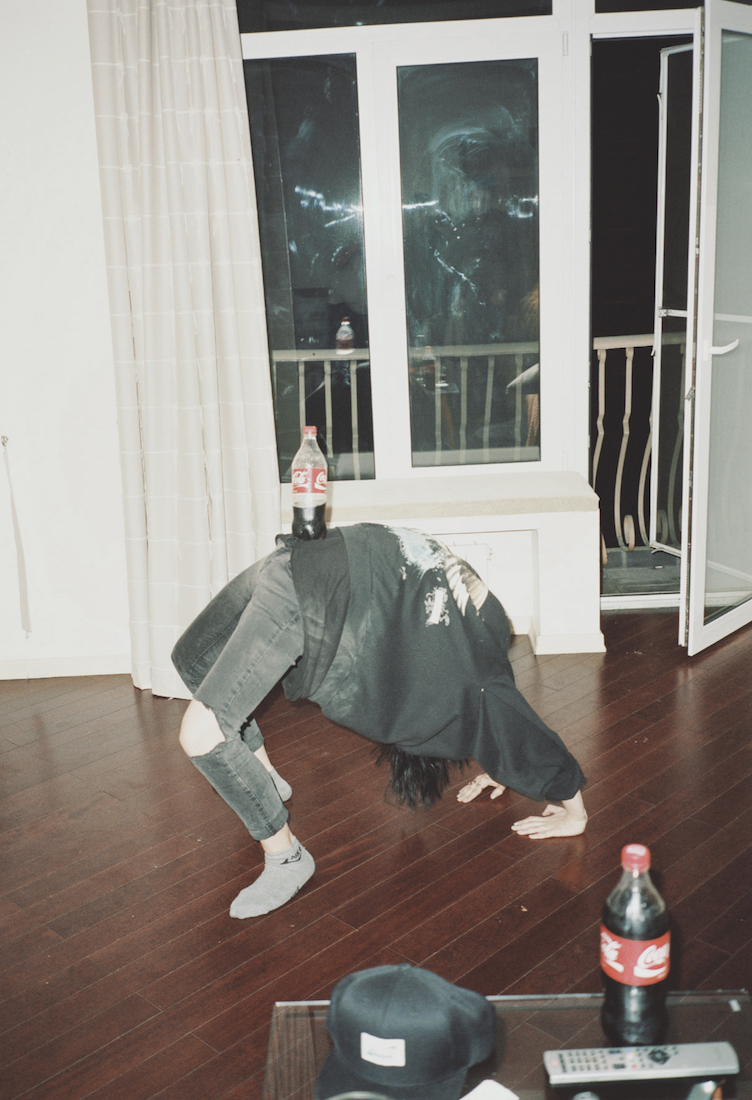

King had traveled to Ukraine right before the political situation between Russia and Ukraine erupted, in the fall of 2013, to document the last moments of calm. He went alone (meeting a local translator there) and stayed in a cheap hotel, then an apartment right on Independence Square, where three months later student-led anti-government demonstrations would mark the true beginning of the crisis. His photographs of the capital’s teenagers, who he met in parks, outside train stations and in local McDonalds, capture the strange, anxiety-laced sense of freedom that hung in the air that summer.

Dimitri, and a group of his friends, star on the cover of King’s new book, Ukraine Youth, which comes out next month through Damiani.

Did you choose to go to Ukraine because you knew the political situation was about to explode?

It wasn’t meant to be a political book but I could see signs in the media. I just thought it was a fascinating country — you could tell it was either going to slip to Mother Russia or the EU. Everyone was rooting for the EU. But when Russia first got wind of the talks Ukraine was having with the EU, they cut off the natural gas to the country for a whole week. The photos are a snapshot of a quiet time in Ukraine’s history that won’t be repeated.

Why did you want to photograph young people in particular?

The kids really are the future of the country and they have no help from anyone. Most of their parents work in factories and after 91 [when Ukraine achieved independence], they make no money and they have no skills. These kids can’t go to their parents and ask, “How do we start a revolution?”

How did you meet people?

It was all street cast. When I first arrived, I didn’t realize that Kiev is the sex tourism capital of the world. So street casting there was super hard. For the first few days, we’d say “Come to a casting at our studio, it’s for an art project,” and everyone would just tell us to fuck off. Then we got the translator’s girlfriend to help us and it snowballed.

How old were most of the kids, and what were they doing?

They were mainly 15 to 22. It was summer, so they were just kicking around. One night some of them took me to a small town near Donetsk, where all the crazy shit is happening now. It was pretty wild; we rented a Soviet-bloc house for 50 Euros from an old lady with no teeth and we just hung out. It was about getting to know the kids, getting their trust, having a good time and learning about their culture.

What was their interest in being involved, do you think?

I hadn’t had a book published or anything, so it was more of a respect thing. And it was just something interesting to do.

What surprised you most about the kids you met?

Just how similar they are. How smart they are. And how connected they are to their country and their government. Also, their powerlessness.

Do you think they’re more politically aware than young people in the US?

Yes, 100 percent.

Is that because there are more obvious political issues? Or are they just more interested?

I think it’s because they grew up with it. They’ve seen the aftermath of the Soviet era, and the dark side of it. The kid who gave me the tattoo works one day a week as a graphic designer and he makes more money on that one day than his dad does working full time in a month. His dad had a job at a factory, doing one menial task — when communism ends, and that’s been your whole life, it’s like, “What are your skills?” But these kids feel a kind of freedom. They want to be part of the EU, they want more for their country.

Have you stayed in touch with them?

Yeah, on Instagram it’s really easy. This one girl shaved her head after I left, during the demonstrations. One of the couples I met has split up, I think. I speak to the producer, Yevgeny, quite a lot. Because I was there alone, I became really good friends with these people. It wasn’t like turning up with a crew, and assistants, which can feel exploitative. They became friends.

What have they told you about the situation now?

At the time, I think they really didn’t want to burden me with that stuff. But after I left, they were scared shitless. The first few months after, I’d ask, “How are you?” and they’d say, “It’s fine, it’s fine.” Then six months into it, they were like, “How the fuck do I get out of here?” But they can’t come to America or go anywhere in Europe. It was when the military started drafting people and some of their friends were being sent off to Eastern border that I saw things change from “It’s cool” to fear.

What do they want to do?

They all want to leave. But they can’t, so they’re just making the most of it. When I was there, what I liked about the project was that it was a time of not prosperity but quiet, where they could be carefree. Now they’re all trying to make hard decisions.

Credits

Text Alice Newell-Hanson

Photography Daniel King