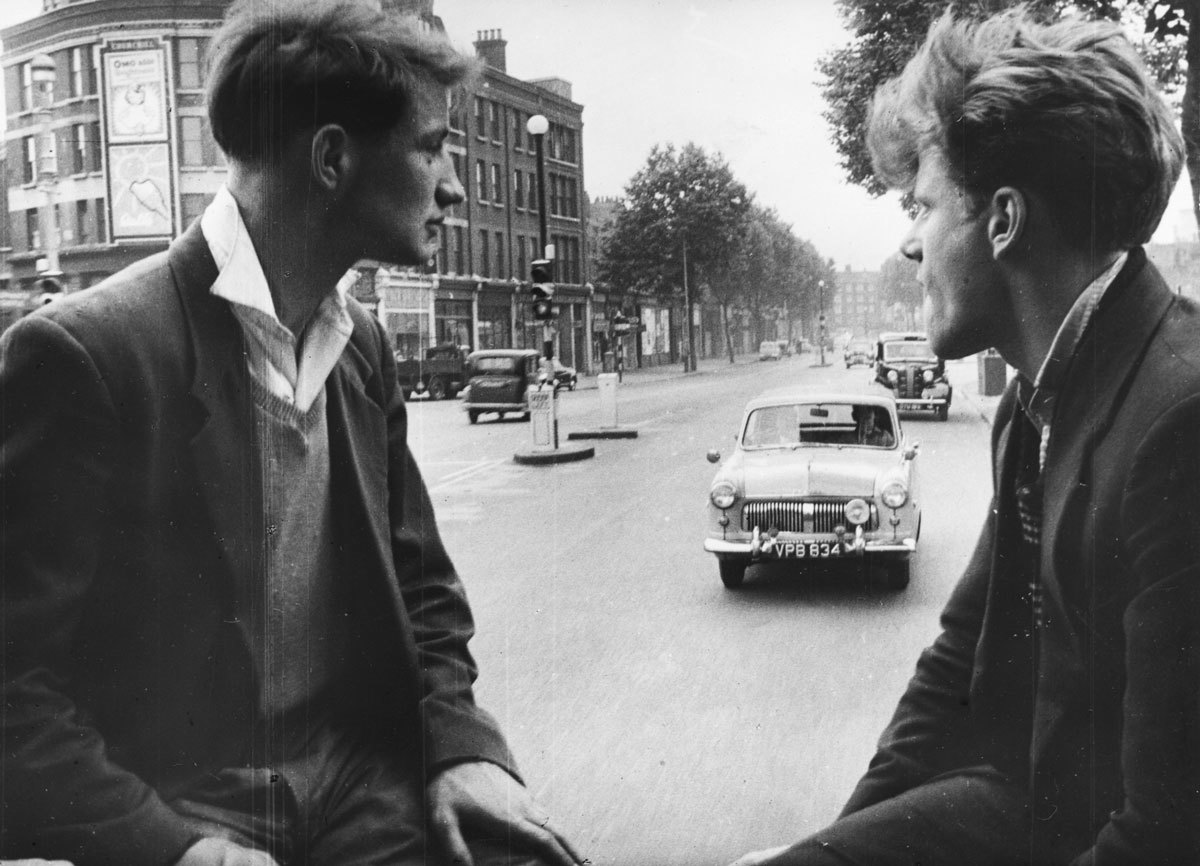

Talking, drinking, dancing. Going to the club, leaving the club, going somewhere else, going home — the promise of the evening and the empty space of the morning after. You spend your days thinking about the nights. You want to go where there’s music and there’s people and they’re young and alive. If this is true now, well, it’s probably been true forever.

The nights — and what young people do with them — are the subject of Karel Reisz’s We Are the Lambeth Boys, which came out in 1959, as the Teddy Boy movement was dying but before the Mod movement had really arrived. On Tuesday October 13, the film shows as part of DocHouse’s Rule-Breakers series, which brings together ten films that have significantly influenced the art of documentary making.

Shot in the summer of 1958 in and around Alford House, a youth club in Oval, South London, We are the Lambeth Boys was sponsored by a car company – Ford – and was part of its Look at Britain series. If Ford’s involvement has you thinking of bludgeoning pieces of branded content, think again. This series of films, which included work by Reisz’s collaborators Lindsay Anderson and Tony Richardson, showed the lives of ordinary British people in a new, sympathetic light. We are the Lambeth Boys isn’t a cartoonish hatchet job on knife-wielding Teddy Boys, it’s a wry and sympathetic depiction of what it’s like to be young and working-class in London.

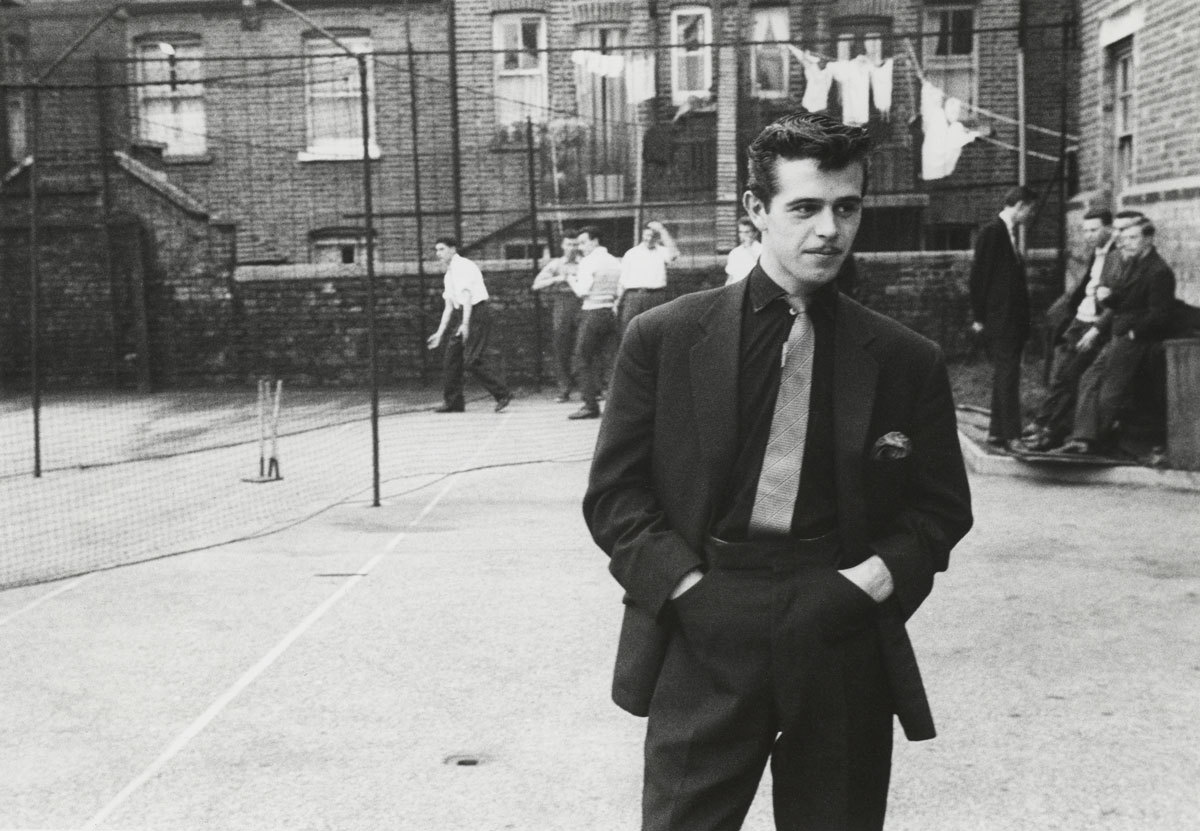

The main characters in the film – save two – are all out of school and in work. There are butchers, dressmakers, and people working in factories. One lad works for the post office, where “life can be dull”, but “he’ll drive a van soon”. Their social lives still orientate around the youth club. The camera observes them and the clipped but empathetic voiceover comments on them. The evenings begin with cricket in the nets for the boys and a “giggle and a chat” for the girls. Everyone mingles, everyone talks – “it’s something to do”, we’re told. It’s really just hanging out, same as it ever was – we just don’t see much cricket being played in youth clubs these days.

The voiceover tells us that this is, “the rowdy generation, that’s forever in the headlines”. The film’s mission is to show us – subjectively and with humor – that this kind of Daily Mail hysteria is bullshit. It’s a film that exemplifies the increasing interest young artists showed in “ordinary” life in 50s Britain. The whole country had won the Second World War and the Clement Attlee government that was voted in by a landslide after created the NHS and established the Welfare State. These things would not have been possible without “ordinary” people.

Politically and culturally, Britain was becoming a more democratic place, and this was reflected in its art. This new democracy resulted in an attack on the staid, middle and upper class work that had gone before it. In the theatre, “angry young men” like John Osborne and Harold Pinter were ripping things up and starting again. The same can be said of the “Kitchen Sink Painters”, a group of young artists that included John Bratby. The complacent privilege of the old world was being exploded. British artists were (metaphorically) killing their parents. Something similar, if more nuanced, can be said of the democratising affect that the work of more quietly radical 50s figures like the feminist sociologist Viola Klein, the academic Raymond Williams and the psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott, had: that here, among other things, was a group of people interested in equality for all, both in society and in ideas.

came out of the Free Cinema manifesto produced in February 1956 by a group of young film directors, including Reisz, which spoke of a belief in freedom, people and the “significance of the everyday”. The everyday is all over the film. The kids talk about fashion, money, dating etiquette and the death penalty. The guys care about their looks just as much as the girls: a good suit costs 15 guineas and will last you for eight months. When it comes to dating, one bloke says that if a girl wants to go dancing, she has to pay, because he’d rather not. Hello, equality for women!

The young men want to be noticed. There’s a scene in which the Lambeth boys go up to Mill Hill in North London, play cricket, swim and then return back south through the West End in a truck. They sing, “We are the Lambeth boys”, as they come back through town. They notice a well-dressed woman and call out to her, “Oi, Sabrina!” “When the boys pass through the West End, the West End remembers for a while that they passed through”, the voiceover says. “And that’s how the boys want it”. These are working class boys letting their city know they are here. The space for this somehow feels freer, in late 50s London, on a rising tide of social democracy, than it does in atomized, 21st century Britain, with its rising inequality and its marginalized communities.

It’s in the anatomy of a night out that the film feels most familiar, most strangely contemporary, even if the dances of the 50s, with their set steps, are quite a long way from the clubs of today. That doesn’t stop the emotional process from being the same, though. “Being young in the morning is different from being young at night. For one thing, there’s no crowd about”, the voiceover tells us as the camera follows some of the characters to work. As the characters work, we’re told that, “In the working hours, thoughts about the evening have time to pile up – pleasant thoughts, maybe, or frightening” – frightening because there is some gang violence in the area and fights do occur.

Later on, we’re at the youth club for the night out. “A good evening starts with talking, and ends with dancing”, we’re told, and we can see the characters out at a dance, hanging out, watching, then dancing and then, when it closes at 10 or 10:30, heading off to Tony’s Fish Bar – the 1950s equivalent of a kebab shop – for some chips or a sit down meal. People in the area complain about the kids going out but then, as the voiceover points out, “there’s more traffic in the streets now, and more lights, and more people”.

As the cigarette smoke rises, as the chips are eaten, as the dancing goes on, the film comes back to its point, as true now as it was then:

“A good evening for young people is much as it’s always been. It’s for being together with friends, dancing and shouting when you feel like it – things we’d all like to do”.

Credits

Text Oscar Rickett

Photography courtesy of the BFI National Archive