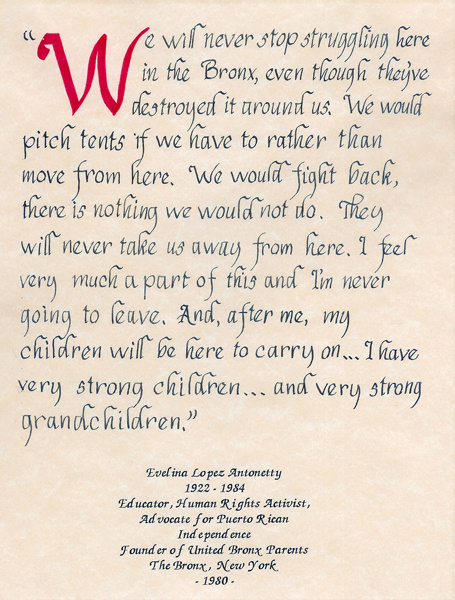

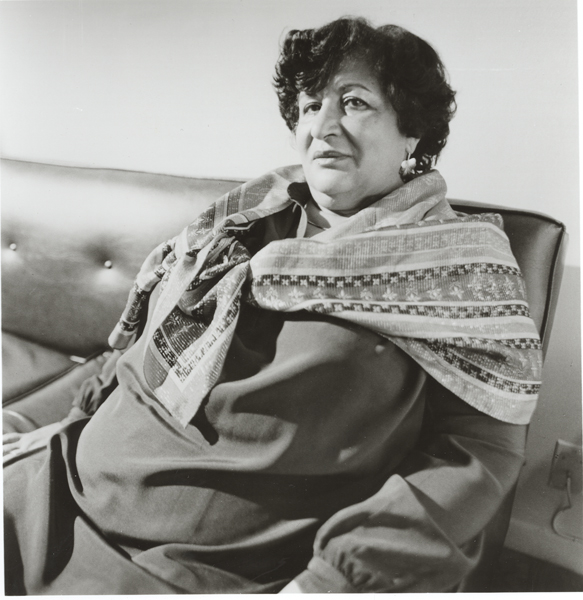

Back when the Bronx was burning, one woman struck fear in the hearts of the establishment: Dr. Evelina López Antonetty (1922-1984), the legendary Puerto Rican activist famously dubbed “The Hell Lady of the Bronx” by a member of the New York Police Department brass. An educator, organiser, and activist, Evelina inspired thousands to rise up and demand their rights. She fearlessly spoke truth to power, making sure politicians understood: “I don’t work for you. You work for me. You do for us first and then we will do for you.”

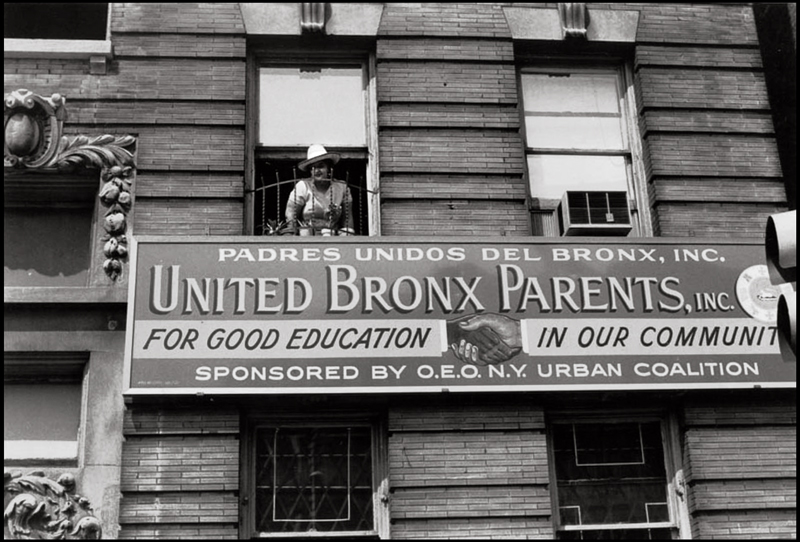

Coming of age during one of the most pivotal eras in Puerto Rican history, Evelina was an agent for change, working with the local community to ultimately reshape the national landscape. In 1965, Evelina founded the grassroots coalition United Bronx Parents (UBP) to oust a teacher sexually abusing children. Six decades later, the non-profit organisation continues its mission to support the community, providing family counselling and social services for women, children and people dealing with housing insecurity and addiction.

“We were all born with PhDs — degrees in poverty, hunger, and determination,” Evelina said. Her relentless crusade on behalf of those in need laid the groundwork for bilingual education across the US school meal programs for impoverished children, and minority hiring in public schools. She established close relations with Civil Rights leaders including Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., understanding that the fight for equality in a nation born of slavery and genocide required broad coalitions across all racial, ethnic and religious divides.

“United Bronx Parents was made up of Latinos, Blacks, Asians, Jews, you name it,” says Evelina’s grandson, photographer Joe Conzo. “It wasn’t about your skin colour, it was about basic human necessity. If there was an issue, she was on the frontlines letting it be known: ‘You’re not closing down this school or this fire department. You’re not going to take this away from my community.’ She would open up her Rolodex, call people, and get a thousand people to show up. She surrounded herself with good people who could move others, and if she were here today, she wouldn’t take credit for anything — she would give it to the people around her.”

During the 1970s, the Nixon White House established a policy of “benign neglect”, denying basic government services to Black and Latino communities nationwide in the wake of more than 100 uprisings following the 1968 assassination of Dr. King. At the same time, the Nixon government launched the “War on Drugs” to systematically destroy those same communities. Evelina became the voice of beleaguered people struggling to survive as her beloved South Bronx began to crumble before her very eyes, under the weight of federal policy further compounded by landlord-sponsored arson. In the space of just one decade, the neighbourhood was torched and reduced to rubble akin to a war zone. She courageously put her freedom on the line, organising protests and sit-ins only to be arrested, and do it all over again.

In 1980, Evelina took on Hollywood when the producers of Fort Apache, The Bronx arrived on her streets. The film, starring Paul Newman, Ed Asner, Danny Aiello, and Pam Grier, combined the neo-realistic pathos of ‘copaganda’ with the campy drama of Blaxploitation films in a lurid portrait of the South Bronx inspired by the 1976 nonfiction blockbuster Fort Apache: New York’s Most Violent Precinct. The film employed the usual trope of racist stereotypes, casting Black and Latino people as murders, junkies and prostitutes, while the cops were portrayed as white saviours, albeit hardened anti-heroes who refused to operate by the book. Dr. Antonetty led the charge against the producers, organising protests and threatening to file suit, defending the people of the Bronx against those who would profit off desecration of the community — and won.

In celebration of her 100th birthday, 19 New York City cultural and academic institutions have come together to create EVELINA 100: A Celebration of the Life and Times of Dr. Evelina Antonetty, 1922–1982, a week-long series of concerts, exhibitions, readings, panel discussions, and teleconference connecting community activists in New York and Puerto Rico starting September 12, 2022.

Evelina’s sister, Elba Cabrera, who at 89 is now the matriarch of the family, will be among the luminaries at the events. Known as La Madrina de Arte for her work at the Association of Hispanic Arts during the 1980s, Elba’s dedication to the community began at home, as the youngest member of a family filled with strong women. “I was born in 1933, [and arrived here] the same way that Evelina came to New York,” Elba says from her home in the Bronx, where she still lives. After Elba was born, Evelina, then 11, went down to the docks of San Juan and boarded a boat destined for Manhattan, where she would live with an aunt in Spanish Harlem. Two years later, Elba, their sister Lily, and mother followed.

A single mother raising three daughters, their mother worked in the sub-basement of the Hotel New Yorker in midtown, doing laundry for six dollars a week. “She never took a day off because if she didn’t come in, she would lose her job,” Elba remembers. “She couldn’t go to parent-teacher visits, take off to visit the doctor, or take care of us when we were sick. Evelina was the one who used to go to school to see how I was doing. She was the leader. She was already married and convinced our mom to move near her.”

In the early 1940s, the family moved to Jackson Avenue in the South Bronx, where they would build their lives and legacies throughout the twentieth century. At the time, there weren’t many Puerto Ricans in the neighbourhood, but the community was otherwise a broad mix of African Americans and Jewish, Irish and Italian immigrants — including a young Colin Powell. “We lived in a building with different people and we all got along,” Elba says. “I have very good memories of the community that cared for each other. We grew up wanting to be public servants and help each other as we were coming up. We come from a family of strong women who were doing things and it just became a part of who we were.”

After graduating high school in 1951, Elba remembers having a difficult time getting a job despite her qualifications. “That’s when I found out what it was to be a person of colour,” she says. “I wound up going to the union where Evelina worked and got my first job. I did exceptionally well.” But despite her professional success, Elba came up against housing discrimination, an issue that has long run rampant throughout New York. She and her husband were fortunate to get on the list with the Housing Authority and secure a home in the Bronx where they lived comfortably.

In the interim, Evelina put the organising skills she had mastered while working for Union District 65 to use and started up UBP. “Evelina was at home with two young children and didn’t want to be bored in the house,” Elba says. “She started talking to people in the neighbourhood, helping them out with things that weren’t being done properly. She realised this was something she wanted to do and that’s when United Bronx Parents was born. She called me and said, ‘I’m going to start and organisation and I need you’.”

Together, the sisters launched UBP in a storefront on Union Avenue and it quickly began to grow. Evelina became a pivotal force in local politics, operating from the outside and using leverage to foster change. She helped transform Elba’s former elementary school, P.S. 25, into the first public school in the US to offer classes in both English and Spanish — a blueprint that quickly spread far and wide. With each success, her impact grew. Today, dozens of schools, libraries, daycares, playgrounds, and streets now bear her name.

In fact, the streets outside United Bronx Parents HQ are named after Evelina and her daughter, Lorraine Montenegro, who ran UPB after her mother’s passing in 1984. “It’s the only mother/daughter street corner in the country. It’s amazing to be part of that legacy,” says Joe, Lorraine’s son. In addition to being the first photographer to document hip-hop as it emerged on the streets of the Bronx during the 1970s, Joe also served in the Army, where he trained as a combat medic before becoming a member of New York’s Emergency Medical Services.

In 2001, Joe picked up the mantle, working as a union delegate at the Fire Department of New York, putting his life on the line when planes hit the Twin Towers. After being buried alive in the rubble, Joe emerged, as so many others did, wrestling with PTSD and survivor’s guilt. But fate had other plans for him, as his then-little known photo archive documenting the birth of hip-hop — as well as Latin legends including Tito Puente, Celia Cruz, and Ray Baretto — was rediscovered by photographer and filmmaker Henry Chalfant for the 2006 documentary film, From Mambo to Hip Hop: A South Bronx Tale.

But it was Evelina who supported Joe’s passion for photography long before the possibility of working professionally existed, nurturing his love and making sure he was on the scene, ready to document community actions. “I will always give credit to her — not that I had a choice where I was going on any particular day,” Joe says with a laugh. He recounts the story of travelling to Washington D.C. to fight for the release of Puerto Rican political prisoners, Lolita Lebrón and Rafael Cancel Miranda. Evelina’s efforts on their behalf helped to liberate them from prison after serving 25 years for an armed attack on the U.S. Capitol in 1954.

Although Evelina has passed, her legacy lives on in the work of UBP and the countless young men and women she helped nurture along the way. “A few years ago, I was giving a lift to a young woman and the other person I was driving told her, ‘This is Evelina’s sister,’” Elba says. “The woman said, ‘Oh my God, do you know what your sister did for me?’ While she was a student, she told Evelina how she wished she could go to a conference in Puerto Rico. After they finished talking, Evelina handed her a check, and said, ‘Just remember to give this forward’. That’s the kind of thing she used to do — and nobody knew.”

EVELINA 100: A Celebration of the Life and Times of Dr. Evelina Antonetty, 1922–1982 takes place in 19 locations across NYC, from 12-19 September 2022.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more on activism.

Credits

Images courtesy of the Evelina 100 Centennial