Today it might be the habitat of hordes of tourists clutching €7 pints of Guinness, but in the 80s, Dublin’s Fownes Street in Temple Bar was filled with ravers heading to Flikkers – one of Ireland’s first electronic music warehouses and LGBTQ+ venues. Back then, clubs had not yet been commodified or forced to shut early and Asylum, the ecstasy fuelled epicentre of the Irish 90s rave scene, was yet to reach its notorious heyday.

Flikkers remains one of the capital’s most iconic gay venues in its history, but it tragically burned down in 1987. Asylum’s tenure ended early too (it closed in 1994 after five undercover Gardai officers were offered ecstasy on arrival). Their fate is sad but also, sadly, not uncommon. Over the last 20 years, over 80% of Irish nightclubs have disappeared, with a host of systemic issues — and the lingering effects of the pandemic — shouldering the blame. Down from about 522 across the country in the year 2000, including 100 in Dublin, there are only 85 dance venues in Ireland today, according to research from Give Us The Night, a group campaigning for modernisation in Irish nightlife laws.

From archaic licensing laws — under current rules in the Republic of Ireland, nightclubs must close by 2.30am, and obtain a Special Exemption Order (SEO) to open later, at a cost of up to €410 per night — to soaring prices and the endless commodification of public space, it’s difficult to find a venue amongst the tourist pubs of Temple Bar and chart-blaring clubs of Harcourt Street which are reminiscent of the legacy Asylum and Flikkers should have left. But that doesn’t mean the hunger for raves in Dublin is by any means jaded or faded. It’s still there: it’s just coming from the bottom up.

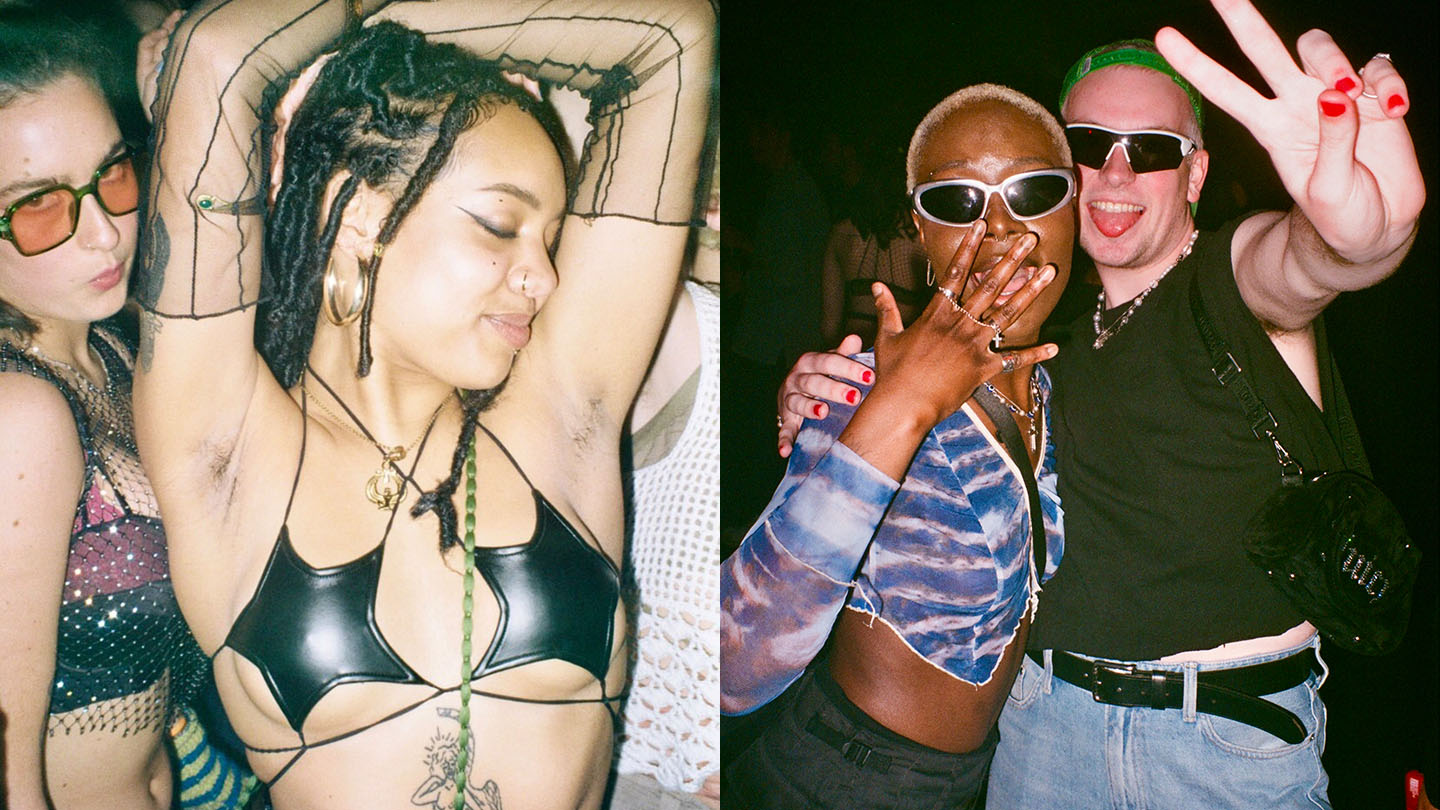

21 year old Dublin-based film photographer Isabel Farrington has captured the yearning for an active rave scene amongst young people in the city. Through collaborations with multiple collectives, Isabel has seen first-hand how the cogs of the nightlife world are being turned by creatives her own age — not for profit, but purely out of a love for it. “The passion these collectives have for creating spaces in a city that seems to be wrung of all culture and amnesties is unparalleled,” she says. “I’ve taken great joy in being a small part of these events and seeing the creation of new spaces with a revitalised energy.”

With few venues to choose from, an imbalance of power can be created between club owners and event collectives who, at times, can barely break even with their costs. Dublin-based electronic rave collective, The Shed Residents, made their mark on the scene after hosting a series of illegal raves last summer. Their rapid success reflected the huge demand for an underground rave scene unrestricted by the pandemic rules or bureaucracy inherent in booking venues.

Following their history of releasing secret locations just an hour before events were due to start, pulling hundreds to forests scattered outside the city, The Shed Residents have adjusted to a more traditional route of booking venues for their nights in the capital. But it’s not been without issue. “Selling out clubs is a great experience, but we have demand for the illegal raves, despite clubs being open,” the Collective say. “It is because Dublin nightlife is so restricted still. Club owners and managers don’t really take collectives that seriously, we’ve been fucked over a few times by venues.”

“It’s about filling the shows, it doesn’t matter to them what kind of collective has the momentum or whether they deserve space or not.”

George Guinness is the co-founder of Thump Techno, another Dublin-based collective dedicated to giving emerging techno artists a platform in the city through the creation and promotion of underground raves and club events. “We have so much talent in our country, but we struggle to keep it here because of better clubs and better scenes elsewhere,” George explains. “The government needs to realise that electronic music is a staple for young people.”

Despite the disconnect between venue owners, the government and young event organisers, there is a cautious optimism amongst the young creatives and collectives at the centre of a burgeoning rave renaissance. The sense of community is strong, and full of passionate collectives working together and pushing to keep Dublin’s electronic music scene alive through a celebration of all the variety Ireland has to offer. The Midnight Disco, for instance, puts on monthly parties centred around an emphasis on contrast, inviting as many artists who play techno as disco, and frequently selling out some of Ireland’s largest and best regarded clubs, as well as abroad.

The collective’s founder Matt Dundon, wants to see more support from the very top. “Unlike cities like Amsterdam or Tbilisi, we have virtually no purpose built nightclubs in Ireland, with some of the best occupying restaurants, theatres or community centres after service hours,” Matt says. “There’s a lot of young people working very hard to make something special in Dublin, but we’re not being provided the necessary support from the state. Support isn’t just about grants for venues and later licensing laws, but also about funding for artists from all disciplines.”

The consistent lack of support from those in power is forcing some Irish creatives to turn towards abstract methods to preserve nightlife. Temporary Pleasure is a collective comprised of architects, event producers and club creatives who believe that the clubbing system is broken. In their largest project to date, the collective are currently raising funds to transform a vacant inner-city space into a venue for six weeks later this year, to host over 40 late-night fringe events that will stage over 100 Irish artists. The project aims to blur the lines between sculpture, venue and community centre as it reimagines the Irish nightclub from the inside out, and change the narrative from over-commercialised to community-based.

Despite the long ignored calls for reform from creatives and collectives across the city, change to the nightlife scene is at last slowly being made thanks to extensive campaigning from Give Us The Night, who’ve helped bring in new legislation allowing for 6am closes over the coming weeks. Made up mostly of DJs and club promoters, the organisation’s founder, legendary Irish DJ Sunil Sharpe, wants to give the artists leaving due to the cultural crisis a good reason to stay. “Ireland places way too much emphasis on its cultural history and heritage in comparison to supporting what’s happening right now,” argues Sunil. “Culturally the city is predominantly a shrine to dead writers, and that’s fine, but let’s start believing more in artists and organisations who are alive too.”

“Give Us The Night are doing a fantastic job making awareness to the government in a hope to change night-time laws,” says Space Collective, another nightlife creative group borne out of a love of electronic music, have demonstrated the demand for late night techno and house events in Dublin through their sold out parties and collaborations with other collectives and labels. They see the new closing times as a game changer for organisations like themselves. “The extension of opening hours is a step in the right direction for Ireland to match the standards of other European cities.”

As one of Europe’s most renowned techno DJs, Sunil has seen first-hand how nightlife regulations have limited the potential for nightlife in Ireland. “Ireland has approached nightlife in a very conservative and basic way in the past, and the failure to reform our licensing laws really caught up with us after the last financial crash,” he says. “The idea that dancing in a nightclub is a form of culture has been a hard sell to authorities here but it definitely feels like the point has landed and been accepted now.”

Noise is being made by talented Irish artists and Dublin-based collectives are working against the odds to showcase this talent, but it’s time that genuine support was provided from above. For Give Us The Night, this begins with an open acknowledgement that culture happens after 10 pm. “Dublin needs access to space, for both permanent and temporary venues,” Sunil argues. “We need new things happening on a regular basis to capture the imagination of those living in and visiting the city.

“If things aren’t changing and refreshing themselves, cities become stale, and that’s what happened here in recent years. The Government can make things like this happen, but again, how committed are they? Time will tell.”

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more on nightlife and clubbing.