“The music would literally shake your internal organs,” says Bill Bernstein of the sound system at Studio 54. The speakers, designed by legendary sound engineer Richard Long, were supposedly shaped so that dancers would feel the bass notes in their flesh as much as their eardrums.

Bernstein first made it inside Studio 54 in December 1977, as a freelance photojournalist for The Village Voice. He was in his 20s and had not sufficiently impressed the doorman on an earlier attempt (“I wasn’t cool enough”). His assignment that night was to photograph a black tie event, in honor of President Carter’s mother Lillian, that had temporarily stopped up the dance floor with banquet tables. When the tables were cleared away and regulars began to trickle in, Bernstein decided to stick around, out of curiosity and “because I thought I’d never be able to get back in.”

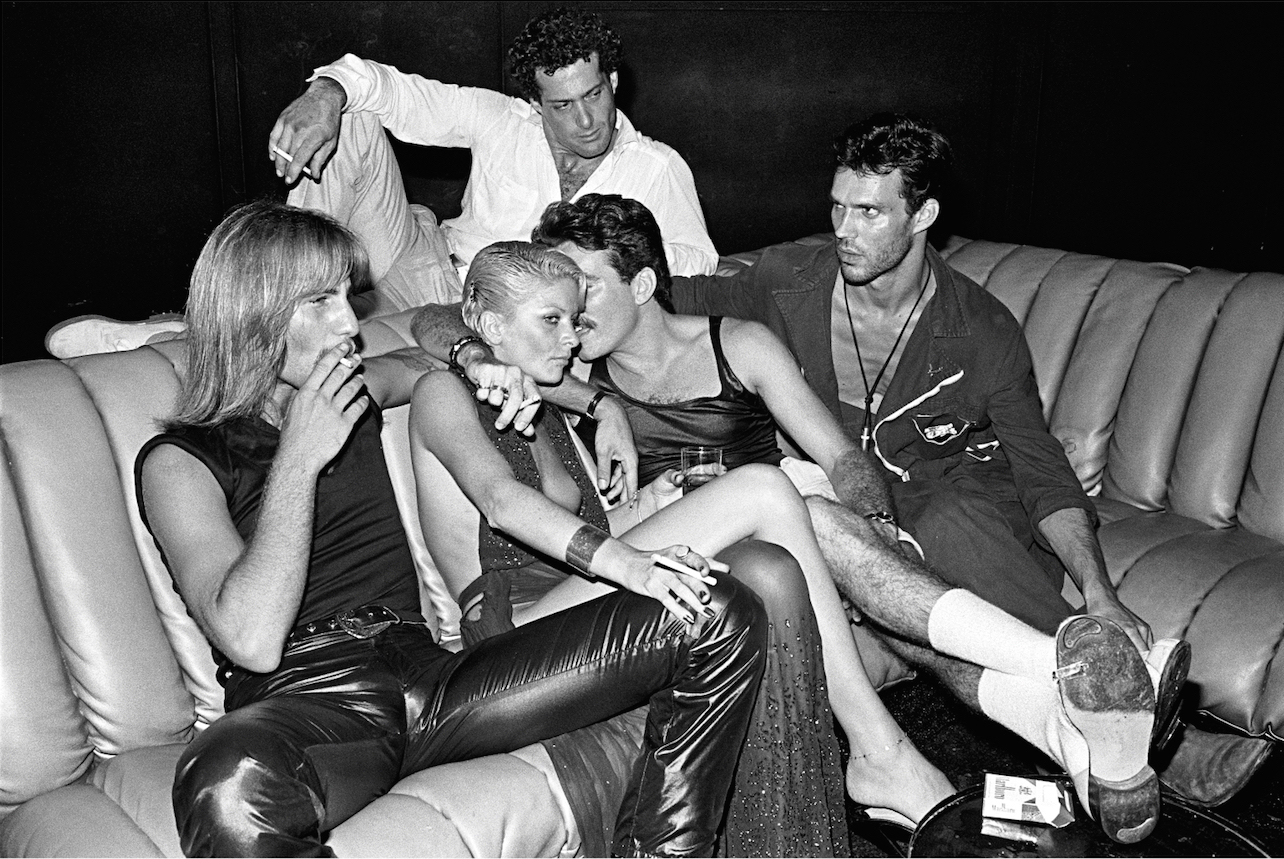

“That night my eyes were blown wide open,” he says, “by the inclusiveness, by the crowd that came in — it was just such an amazing mix of people. They weren’t in cliques, in different corners of the room, they were all mixed together, all dancing together, all partying together.”

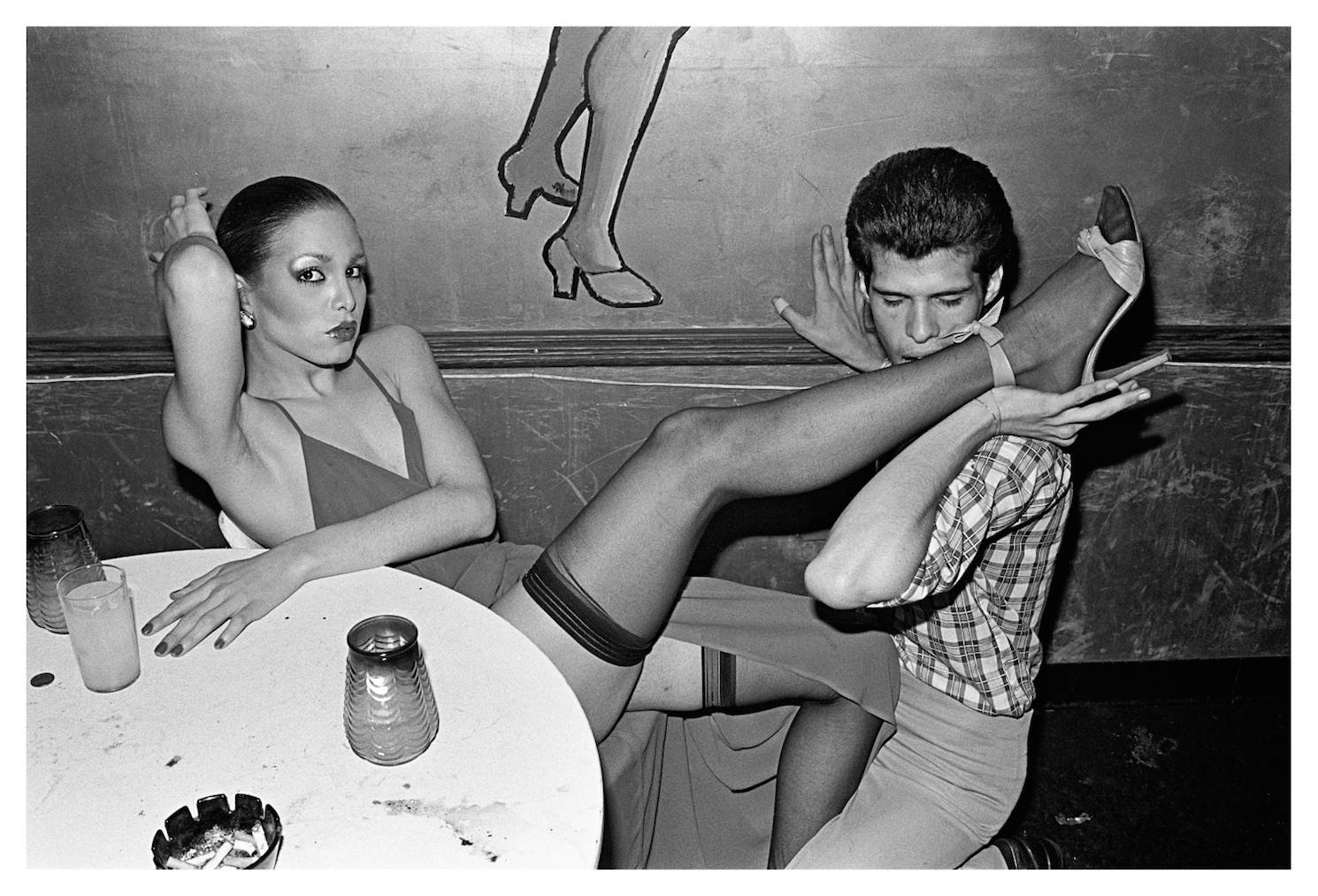

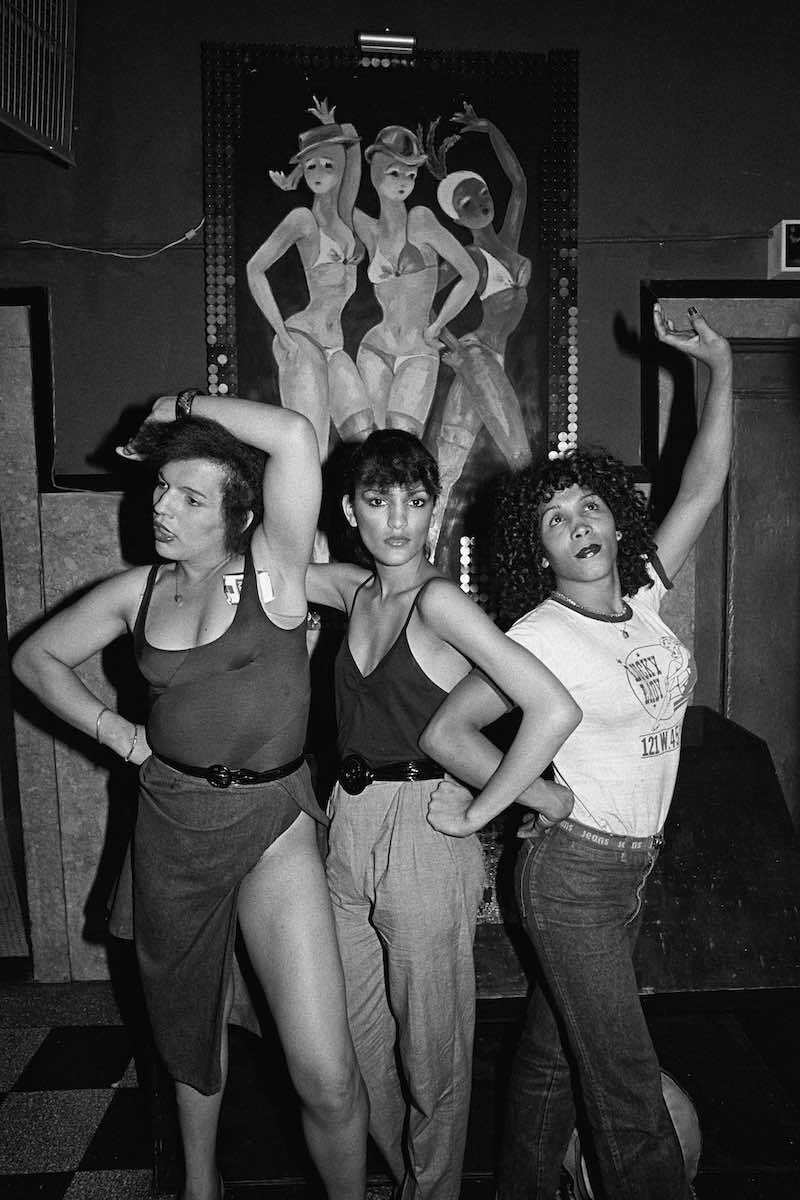

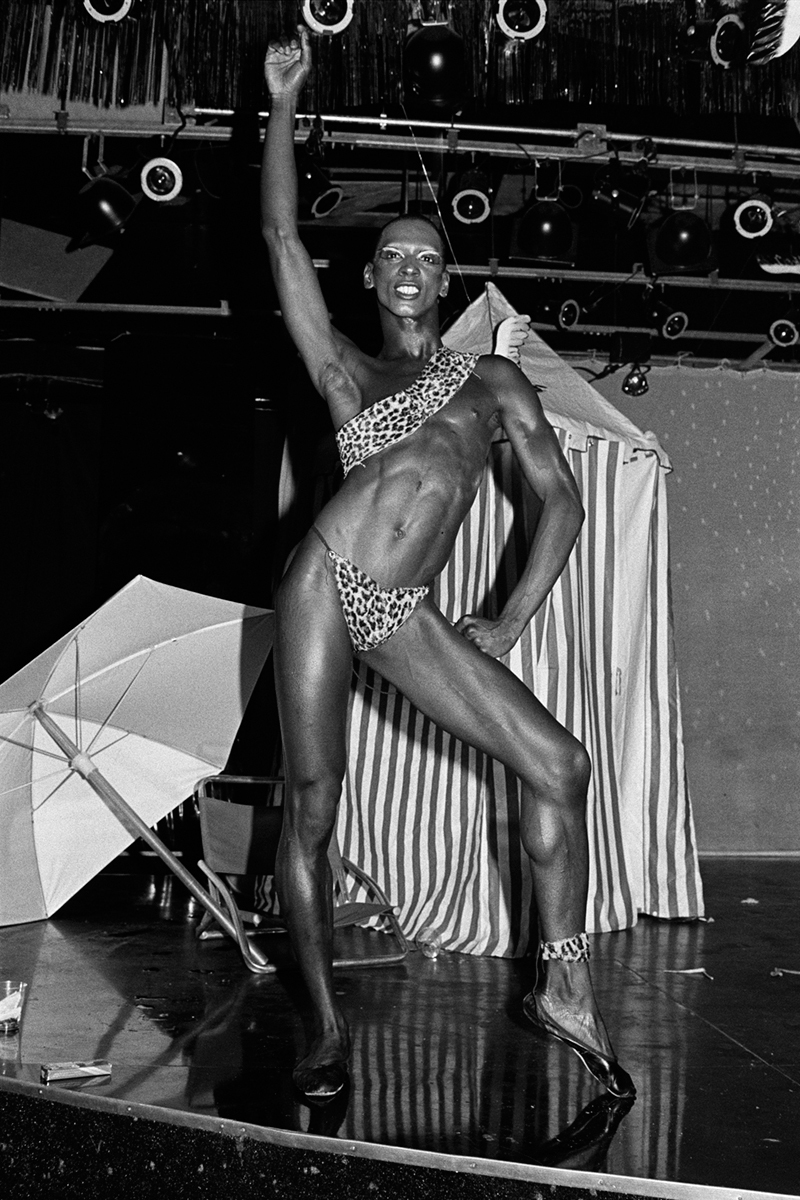

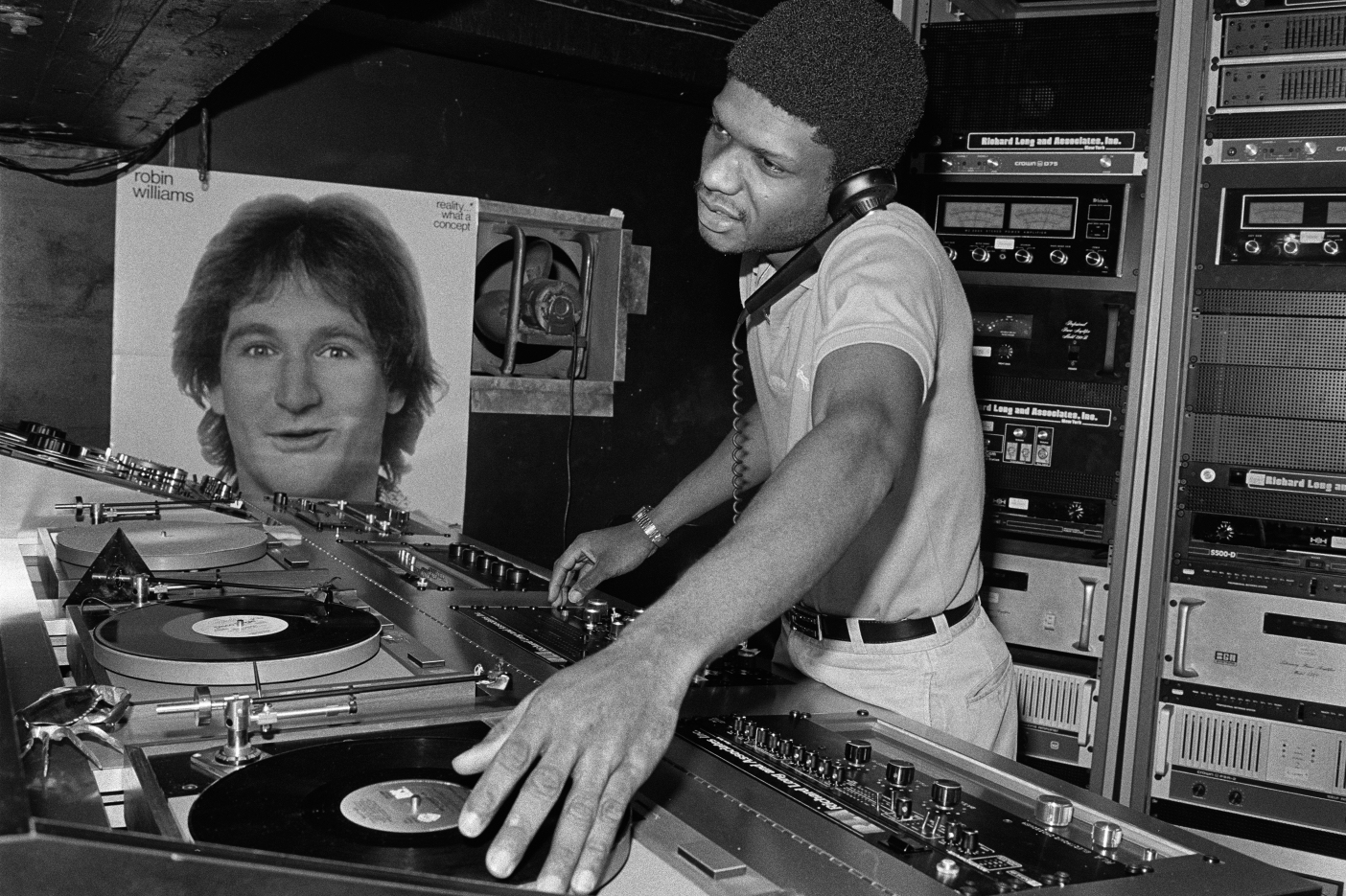

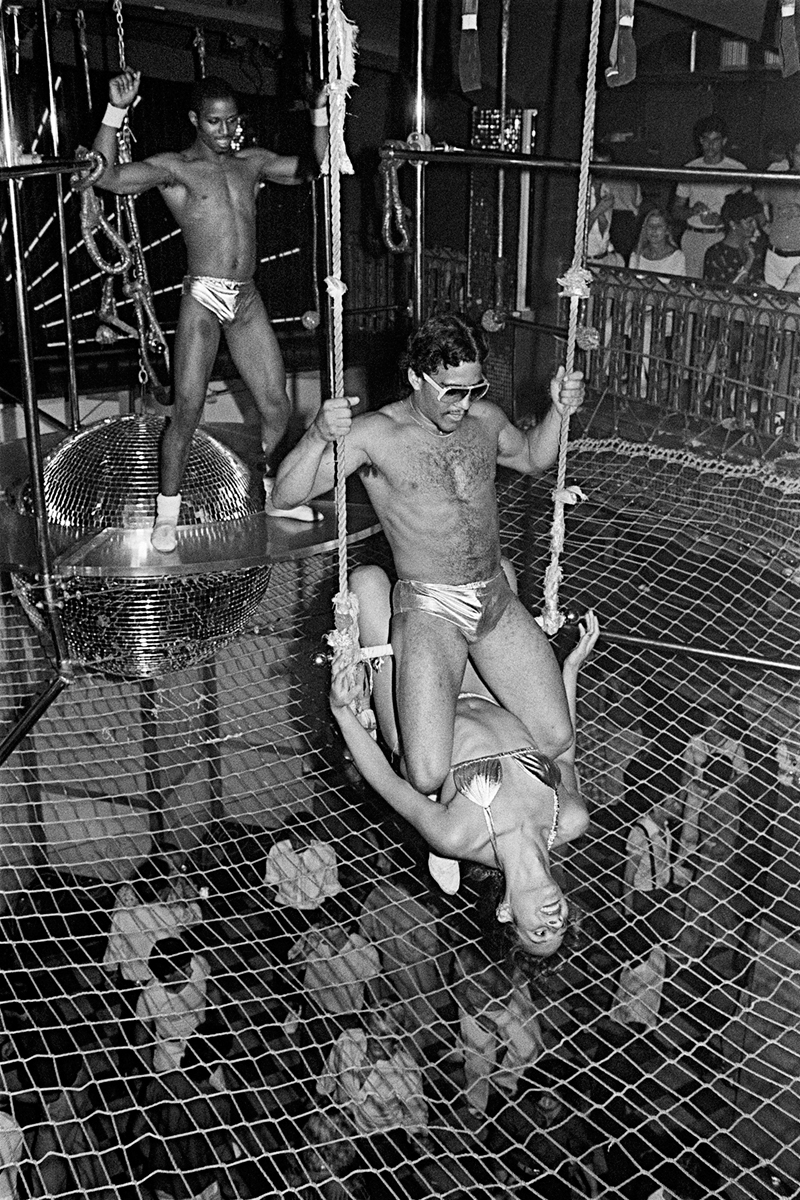

Over the next two years, Bernstein visited, he guesses, over 26 different disco clubs in New York, Long Island, and New Jersey. He captured the glittering people at Le Clique, Hurrah, and Xenon in Manhattan, the legendary Ice Palace in Fire Island. His images show the lamé-clad flying acrobats at GG’s Barnum Club, legendary DJ Larry Levan playing at Paradise Garage, the leather couches at Studio 54, spilling over with tight-panted party people. “Underneath all the trappings and tinsel and mirrored balls, and even the music, there was something else going on,” he says. “It was like a victory dance for gay people post-Stonewall, for the women’s movement, for African Americans and Latinos, for equal rights. It was like, ‘We did it and here we are and we’re having a good time!'”

Night Fever: New York Disco 1977-1979, The Bill Bernstein Photographs, a new exhibition at the Museum of Sex, celebrates disco’s all-inclusive attitude towards sexuality. A selection of images from Bernstein’s 2015 book Disco goes on show tomorrow inside an immersive club environment complete with thumping Richard Long speakers.

What was disco’s reputation when you started documenting it, at the end of 1977?

It was seen as a fad. But disco was happening very much underground throughout the 70s. It’s important now to look at and remember this idea of an inclusive culture. Aside from the fact that economically New York was in terrible shape, homophobia was rampant, transgender men and women were not really accepted, they were seen more as the exception, as oddities even. So to have a unique place that everyone could go to regardless of color or any orientation, and celebrate and dance was unique. It was a unique period.

I just read an article in German Rolling Stone about disco, illustrated with pictures from my book, and it talked about the beginning of disco as being basically during Nazi Germany, like an underground place for people who hated Nazism. A place for them to go and turn it all out and dance. So it was very similar: a place to go and get away from the real world. An all-inclusive, democratic environment to party in.

Then disco became very mainstream when Saturday Night Fever happened, in December 1977. All of a sudden it went from being an underground scene, with places like The Loft, run by David Mancuso — who actually just passed away this week — and a place called The Gallery, with Nicky Siano, who later became the first DJ at Studio 54. Studio 54 was the first and sort of premiere disco club to appear on the scene. And of course it became legendary, infamous! It wasn’t the only disco in town. But it was the first I went to. I covered the whole range of clubs that were happening in that period.

How did you decide which club to go to on which night?

I really didn’t go to special event nights. To me, that was maybe when the celebrities were going to be there. I was more fascinated by the people who weren’t celebrities but who would transform themselves for the night.

Who were some personalities you got to know and photograph?

There was Rollerena, who was at Studio 54 and Xenon and appeared all over the place. I heard that she was a Wall Street banker during the day and lived as this kind of fantasy fairy princess with a wand at night, on roller skates. She was so much a part of the night scene, and also the West Village scene. She used to roller skate down the street and bless people with her wand. Then there was Disco Sally, who was 76 years old. Her husband had died and she was heartbroken, so she went out to a disco one night and became a regular at Xenon and Studio 54. She was born again, in a way, into that lifestyle. The couple on the cover of my book I would see at different times. They were like performance artists almost. One night they dressed up in safari gear and set up a tent in the middle of Studio 54.

Was it clear already in 1977 that disco had a time limit?

I didn’t know what was going to happen. I thought, “How much bigger can this get?” Because it was everything for a couple of years. Radio stations were all disco. There was rock and roll happening concurrently, but disco was just so, so big. My timing was kind of perfect, by sheer coincidence: Studio 54 opened in 1977 and closed in 1979, and that’s the period that I photographed in. Not that Studio 54 was the only place for disco, but it was a huge force behind it. The real thing that I think brought disco to a turning point was AIDS. When I started shooting at discos it was called “the gay cancer.” People would talk about their friends dying of this disease and that there was something going on, but it was a big question mark. Then finally in, I think, early 1981, they announced that AIDS was a virus. There was so much fear and panic around it — that you could be talking to someone with AIDS and they’d accidentally spit on you and you’d get it, or if they were sweating and shook your hand. The scene really changed. It continued, but it changed.

How else would you explain why disco died in the early 80s?

There was the famous cultural backlash against the music itself, with the demolition night in Comiskey Park in Chicago, where people burned their disco records. I think people were getting tired of the music and they wanted rock and roll back. All of these stations had gone from rock to disco overnight and stayed that way for a couple of years, just because it was such a powerful economic driver. But then people got tired of it. It was like the hula-hoop, you know? After a while it’s like, “Ok, I did that.” But it was also much more significant than the hula-hoop, culturally and socially.

How do you think that spirit of inclusivity and progress compares to today’s political climate?

When my book came out in 2015, the equal marriage amendment had just passed, and there was a conversation about how confederate flags were not a good thing in the South, trans people were allowed in the military, all these things were happening. All the things that I was really amazed by back in the 70s were all of a sudden becoming part of our culture. I think that every time something like that happens, you have a backlash, and that’s part of what we’re experiencing right now. But I do think the majority of people want to be inclusive, where everyone is accepted. I think inclusiveness will overpower and overcome.

“Night Fever: New York Disco 1977-1979, The Bill Bernstein Photographs” is on show at the Museum of Sex from November 18, 2016 to February 19, 2017.

Credits

Text Alice Newell-Hanson

Photography Bill Bernstein