Minimalism is arguably the most misunderstood term in fashion. Of course it connotes simplicity: clean lines, monochrome palettes, the absence of filigree. But there’s something else to it, Minimalism promises anonymity. Clothes without identifying features makes their wearer hard to pin down, and difficult to remember, you could be anyone. In 2016, that proposition is perhaps more appealing than ever before.

Designers took to minimalism differently around the world. The Europeans, the Japanese, the Americans all diverged. The New Yorkers — Donna Karen, Calvin Klein — are certainly responsible for commercially popularising the look, but the Europeans incubated the movement. They went high-concept — Jil Sander, Margiela, Helmut Lang — re-contextualising the women in their clothes, designing from the inside out.

Across the ocean Japanese designers played with the concept; pushing minimalism further and further away from what other designers had accustomed their audiences to — often, Rei Kawakubo didn’t want the women in her clothes to look human at all. With every successive show, she seemed to ask, “Does this count as minimalism? How about this? Are you sure?” She played a delightful game with editors and audiences.

Every minimalist school has its charm: here we recount the seminal shows that came to define the movement the world over.

Maison Martin Margiela spring/summer 1993

No story on minimalism would be complete without him: the magical man behind the curtain. Margiela wasn’t necessarily obsessed with clothes, he was obsessed with making them. He liked to tear them apart and rebuild them: process was paramount, he was fascinated by construction. Thus, Margiela’s minimalism never abandoned tailoring or fine construction. The designer’s spring/summer 1993 presentation perfectly married the decade’s minimal staples — silk slips, sheer tanks — with more elaborate renaissance vests and billowing bell sleeves. A young Kate Moss wore a bolero crafted from ivy. His models were Shakespearean heroines transported from a Midsummer Night’s Dream to the inner-city streets of Paris. Though his minimalism would never saturate the market in the same way as Calvin Klein’s, the enduring significance of Margiela’s high-concept approach cannot be overstated.

Calvin Klein spring/summer 1994

For a time, rumours swirled that Klein was lifting designs from Helmut Lang, but the Bronx native took great pains to prove that wasn’t the case. Indeed, the timeline of the accusation wasn’t right. In fact, some of designs that critics pointed to as evidence of plagiarism had come out of Klein’s studio slightly before Lang’s. At the end of the day, the two men had simultaneously intuited exactly what people wanted to wear in the 90s — less. Klein’s spring/summer 1994 collection proved him as a singular designer, a man at the height of his craft. It was the smallest details — a slight tulip-shaped flair of a skirt — that elevated the collection to such great heights. The colours weren’t just beige, but variants on the colour of women’s skin. “Face powder-y colours,” Klein told CNN. In the years following, few designers have managed to cut a slip quite so right.

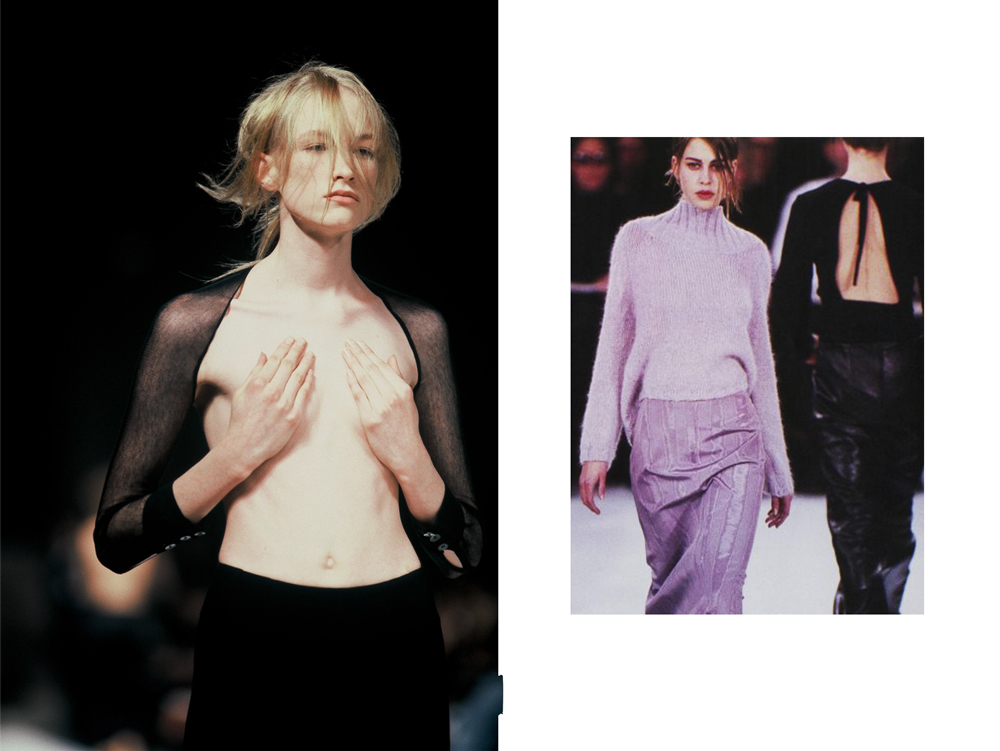

Ann Demeulemeester autumn/winter 1995

Ever since her debut in 1987 Demeulemeester had worked with a very restrained monochromatic colour palette. In fact, her very first collection was shown as a gallery exhibition of black and white photographs. By the mid-nineties, Demeulemeester’s aesthetic was well established and loyal buyers would fill department store floors with her collections. With her legacy and commercial success secure, the Belgian designer began to experiment with flashes of more playful shades — lilacs, umbers. In this collection, she cut swathes of fabric away from model’s bodies, most memorably exposing the entire torso of one. It was, by her standards, a bold step forward.

Jil Sander autumn/winter 1995

Sander was one of the first — and last — minimalists. She adhered to the aesthetic for well over 30 years, always guided by the principle that she designed for women like herself: enterprising, ambitious and selective. After all, Sander was the first female chair of a publicly-owned business in her home country, Germany. The designer would alway try on her own clothes to see how they felt on the body; it was this approach that separated her from others. She conceived of clothing differently, perhaps more purely. That steadfast pursuit of simplicity drew occasional criticism — editors felt Sander wasn’t evolving, and her designs were too austere. Of course, she never wavered, and today is celebrated as one of minimalism’s great heroines. A cursory look at her autumn/winter 1995 collection shows us a woman ahead of her time. She sent models of colour down the runway with their natural hair — and we’d love to get our hands on one of those shining metallic suits right about now.

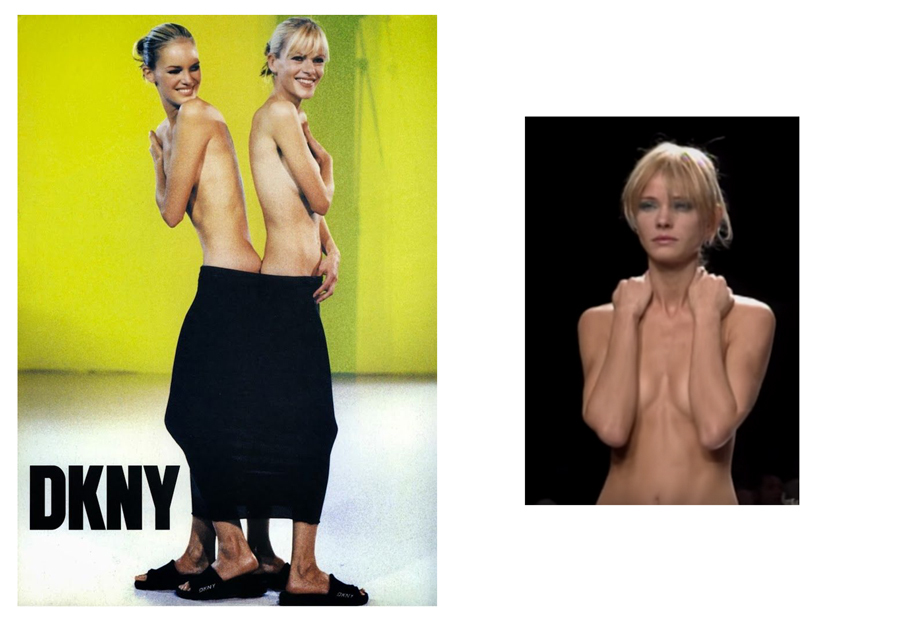

DKNY spring/summer 1995

Donna Karan has always insisted she isn’t a fashion designer: she makes clothes. Much like her New York counterpart Calvin Klein, Karan’s minimalism wasn’t conceptual or esoteric. She just wanted to make easy clothes that would satisfy the desperate “I don’t know what to wear” feeling. She succeeded — her clothes were useful and beautiful. Karan’s spring/summer 1995 collection soared especially high. Every model she sent down the runway was wearing the purest iteration of their garment: the simplest silk slip, the perfect sheer tank. She was the queen of basics. This collection is also notable for its opening; Karan, usually not one to pull stunts, sent the first four models down the runway topless in low slung tube skirts, hands guarding their chests. The according campaign became better known than the collection itself. Peter Lindbergh photographed two models squeezed into a single skirt, giggling. It summed up DKNY well: more fun than fashion.

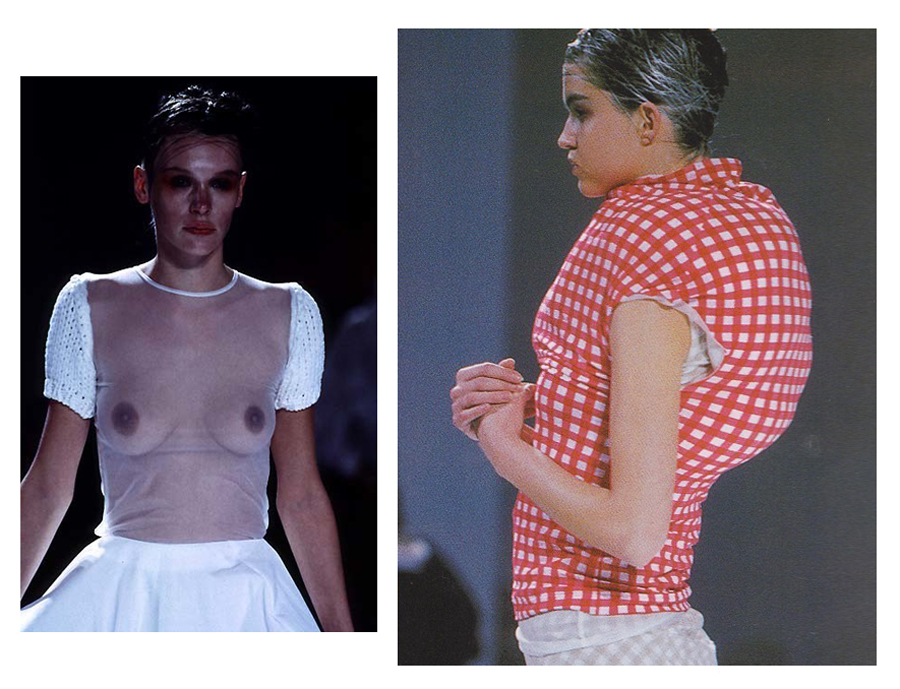

Comme des Garçons spring/summer 1997

A hit with critics, a flop with buyers: that’s how Rei Kawakubo’s ‘Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body’ collection was received. It’s little surprise — the designer’s dresses redrew the shape of model’s bodies, clinging tight in uncomfortable places, using padding to swell their backs in hunches, attaching growths to their hips. The silhouettes were deliberately unflattering. Today, it’s colloquially known as the Lumps and Bumps collection. Kawakubo shied away from any adornment: there were no diamantes, embroidery or beading, just experimental forms and simple patterns. In the years since, the collection has sparked essays on disability, scoliosis, and beauty — it is a testament to Kawakubo that she could gesture towards such complex concepts with so little fabric. The dresses are now held by major museums around the world.

Helmut Lang autumn/winter 1999

In the 1990s Helmut Lang’s influence over the fashion world was utterly unparalleled. When he moved to New York in 1997 he decided he’d show his collections before the city held fashion week (at the time, the order of fashion month ran Milan, London, Paris, and finally, New York). Donna Karan and Calvin Klein followed suit, rescheduling their own shows to coincide with Lang’s. Singlehandedly Lang upended fashion month, and today, New York is still first on the calendar. We could select any of his collections from the decade for this story; they were all masterful examples of imbuing minimalist garments with a secondary layer of meaning, something naughtier, darker — latex winking at BDSM, vests cut like bulletproof jackets. Let’s settle at his autumn/winter 1999 collection, distinguished by the flashes of silver and orange. Lang had made motorcycle pants for a ride into space — the entire cast was ready to take off into the new millennium.

Junya Watanabe autumn/winter 2000

Junya Watanabe called this collection “techno-couture” — a meeting of traditional craftsmanship and man-made fabrics which behaved in strange, exciting ways that no natural fibres could. The promise of this new technology excited Junya, who focussed this show on the malleability of these new fabrics; building sculptures, not dresses. On models, the garments were masses of perfectly symmetrical honeycomb shapes which blossomed off their bodies; but when taken off, each could be collapsed and folded into a simple rectangle of fabric, some small enough to fit into an envelope. The show, in its basic palette of blue and cream, was an incredible feat of design. It proved the Japanese designer’s self titled line, Junya Watanabe Comme Des Garçons, was as influential as its parent brand, and Junya himself an equal to his mentor, Rei Kawakubo.

Credits

Photography Junya Wantanabe via, Comme des Garçons via, Calvin Klein via, Helmut Lang by Juergen Teller courtesy Helmut Lang Studio, Ann Demeulemeester courtesy of Ann Demeulemeester Archive, DKNY via Peter Lindbergh and YouTube, Jil Sander via YouTube, Margiela by Tatsuya Kitayamat via.