Jim Jocoy was a student at UC Santa Cruz when he first saw The Ramones play at San Francisco’s Savoy Tivoli Theater in 1976. That April, the New York native four-piece had released its incendiary debut album, and set off on a nationwide tour that changed American music and culture forever. “The Ramones were sort of like Johnny Appleseeds in that every town they went to, bands formed, people created zines, and zines fertilized a kind of fashion culture,” Jocoy recalls. “Together, it created this wonderful energy that I got swept up into.”

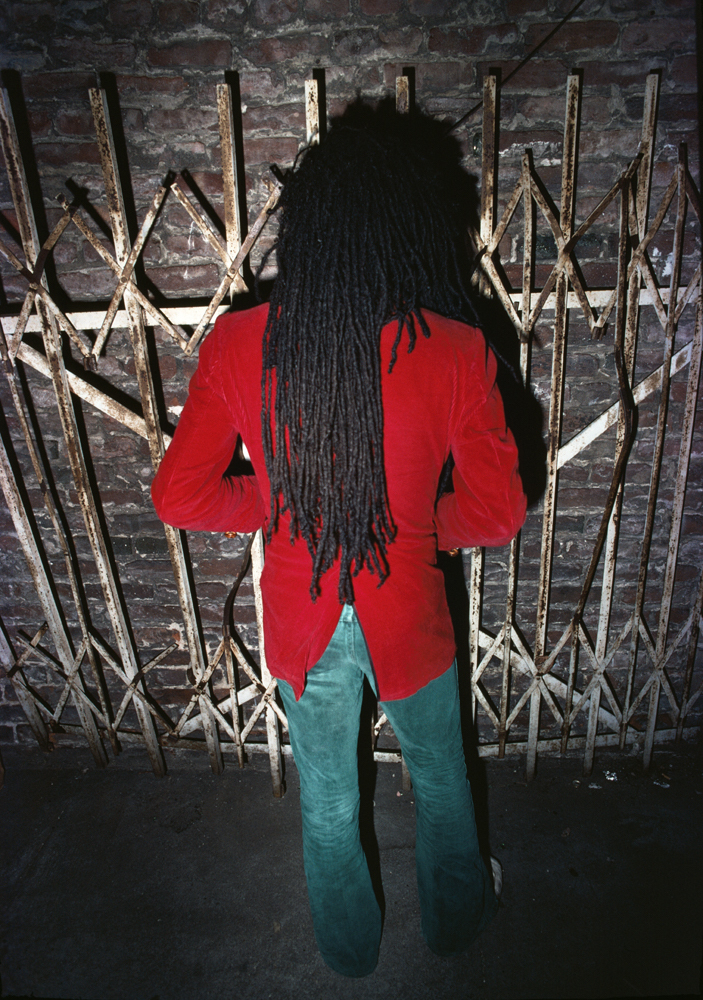

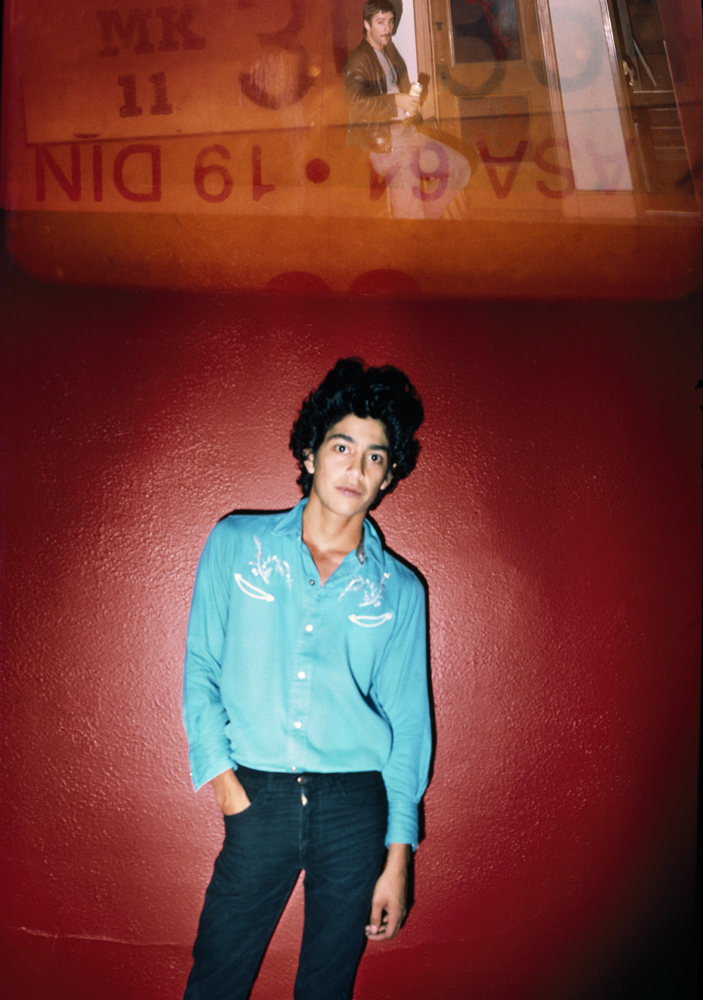

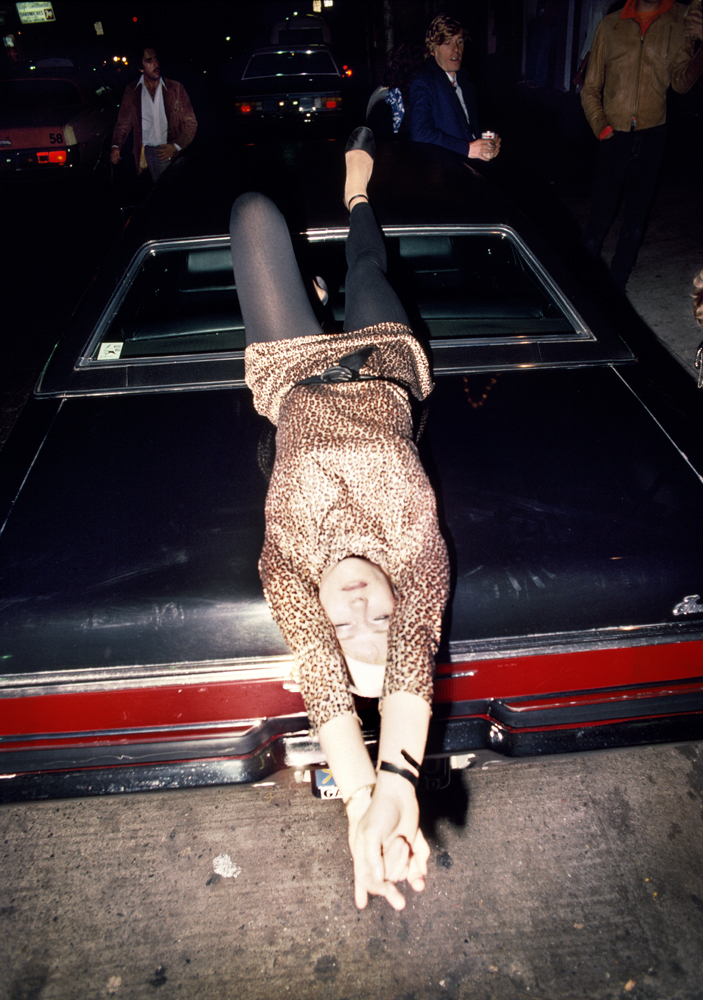

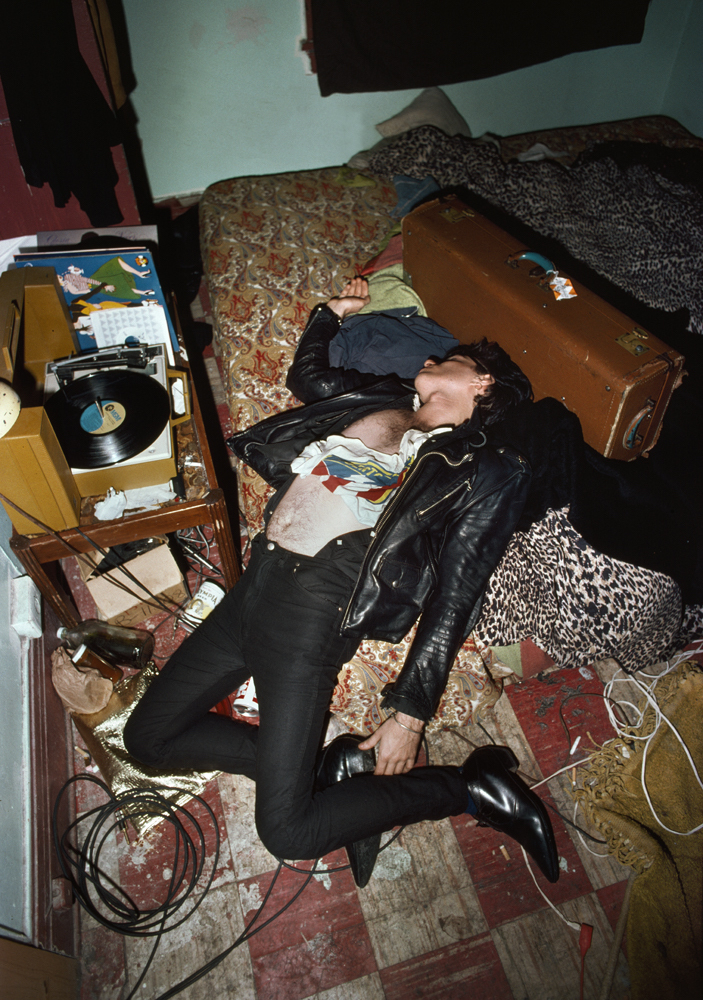

By the following year, he’d left school and was photographing San Francisco’s flourishing punk scene. Jocoy took candid snaps while getting ready for a night out at a show or a club, shot seminal bands like X and The Nuns playing live sets, and made documentary-cum-fashion portraits of this new culture’s cast of nocturnal players.

While others photographers across the country captured their local punk scenes in gritty black and white, Jocoy made vibrant color pictures using color transparency slide film. If his hues recall the kind of saturation, light, and shadow found in Nan Goldin and William Eggleston’s photography of this same period, it’s because the NYC chronicler and Memphis-born master shot with slide film, too. In each case, even the most quotidian object or quiet scene comes alive with rich, evocative color.

Jocoy was able to make so many slides in the late-70s thanks to his day job at a copy shop in San Francisco’s South Bay. That shop was home to the first color Xerox machine, which could produce color images through a carousel slide projector attachment. Management had an arrangement with Xerox that stipulated after making a certain number of copies, they’d be billed for the services differently. “So I made an agreement with my manager that if we hadn’t hit that amount, I could use up the rest of it,” Jocoy explains. “That’s how I generated volumes and volumes of images, and it’s what drove me so strongly to take pictures. After I stopped working there, I couldn’t afford to make them anymore!”

The photographs were exhibited only twice during the period in which they were taken: at a show at San Francisco State University that featured the prints he’d made at the copy shop, and at William Burrough’s 70th birthday party, where they were presented as a slide show. Now, these photographs form Order of Appearance, a new book published by TBW Books. This Friday, an exhibition of its photographs will open at San Francisco’s Casemore Kirkeby Gallery. We spoke with Jocoy to learn more about how San Francisco’s urgent punk scene reacted against its historical hippie era, and why it’s critical that creative people come together.

How did you first begin taking photographs?

My dad always had cameras around the house, and was very okay with me handling them. So I’ve always been comfortable with a camera in-hand. When I was in high school, I took some courses about how to develop black and white in a dark room. But I never really studied photography other than my own interest. I’m self-taught, and I like to think of myself as an artist rather than a professional photographer. The camera is a tool among various mediums including drawings and collage work.

Back in the 70s when The Ramones were touring around, I thought it’d be fun to go to a thrift store and buy a toy camera to take to the show. So after that, when I was going out taking photographs of things that I’ve become recognized for, much of the time, I was using those toy cameras. I had the vision of what I wanted to do, and I just kind of made whatever camera I had work for me.

I’ve always been interested in music; it’s something that’s fundamental as to why I started taking pictures at clubs and shows. I would hear American rock music on military base radio stations when I was younger, and I must have been 11 or 12 when I saw Little Richard, The Everly Brothers, and The Beatles in the early 60s. I remember sneaking out in middle school to see a James Brown concert in El Paso in 1967.

What drew you to San Francisco?

My dad was in the military and retired here, so we’ve lived in the Bay Area since the late 60s. When we moved here, the hippie era was kind of dying off where it had really flourished just a few seasons earlier. I think the Summer of Love contributes more to the popular imagination of what the city was like, but San Francisco then was kind of dark, and heavier. And when we moved here, punk rock was on the horizon. My friends asked me if I wanted to go see The Ramones back in 1976. That was what started my interest in punk rock, and the fashion and culture it engaged with. I was very driven to be around creative people and experience everything.

How did you see the city’s punk scene crystallize a decade after the Summer of Love?

I welcome and I’m open to alternative lifestyles in various manifestations, including the hippies. Although I wasn’t of that generation, I still respected it. And at the time, I think I reacted the way a lot of others did in terms of how the ideas that ignited the counterculture morphed and became too mellow. The feeling, generally, was that everything was moving in a direction where it was too processed and predictable. It needed something to kick it up into a new place. Punk was kind of like Dada; it was upending things and stirring things up — it broke things down to rebuild them. It really said, ‘Let’s clear the table of what we see now.’ People were motivated to get out there and create. Punk collected this energy that was more darker, more cynical. It infused a pulse that had been missing among the mellowness.

When you were at a punk show or a club, what drew your eye to photographing a particular subject?

At that time, I divided my photography into three areas. The first was a kind of formalized portrait for which I shot someone up against a wall. I call it my bug collection, because I thought of it as if I was going out and capturing these exotic creatures of the night, like an etymologist. I wanted to see what they looked and dressed like from head to toe. Like a bug, you want to see every little detail. The second group of pictures was pretty much live shots. I loved getting into the pit and being up front to capture the bands performing live. The third — which is more of what Paul and Lester from TBW Books collected with this book — was casual shots. Before going out for the evening, I’d be at friend’s houses getting ready, getting dressed, loading up my cameras, and shooting.

When Paul and Lester contacted me about making the book, I gave them all my slides from the time. After about two months, they told me they had something together and asked if I wanted to take a look at it. I saw it, and it was like going to a baby nursery. I counted all five fingers and toes on every limb, and I said ‘I don’t want to touch this!’ I had no edits at all — before, during, or after. I loved their sequencing, everything. And the reason why is that they culled a kind of vulnerability from my pictures. They created this intimate energy and vibe I didn’t even realize I had in my photography — this quiet, calm beauty that I see of young people engaged and interacting with this dark cultural tapestry that’s starting to happen in the background. For them to really pull that out of my pictures, to kind of get that strong feeling, it’s masterful. I really give them so much credit; I’m just stunned at what they were able to do.

Let’s talk about punk’s relationship to the political climate of the era.

In California, we saw what was happening with the governor we had, who eventually became the president, and who created an atmosphere — and affected a health crisis — that many people in the music and creative worlds were reacting to and rebelling against. I will never forgive Reagan for all of the things he could have done to prevent suffering of people I know personally. And historically, I think of how many people died of a disease that could have been alleviated. Now, we’re at a critical point where this planet is an ailing thing. You really don’t want to see those catastrophic consequences again, where you should have said: ‘Protect this. This is precious.’ We’re at that place again.

And I’ve started to feel as though I have that same kind of energy now — like I have to react because of what I see around me. I want to think people are good, but it’s hard when this atmosphere has been and is being fertilized. It’s similar to what I experienced 40 years ago, and it has such horrible consequences. Things might not look good, but you get better when you react to it. You get good.

‘Jim Jocoy: Order of Appearance’ is on view at Casemore Kirkeby Gallery from June 16 – July 29, 2017. The exhibition coincides with the launch of Jocoy’s book of the same name, published by TBW Books. Jocoy will sign copies of the book during the exhibition’s opening reception on June 16 from 6-8 pm. More information here.

Credits

Text Emily Manning

Photography Jim Jocoy, Images courtesy Casemore Kirkeby Gallery, San Francisco / TBW Books