Sex work as a subject for photography is one that has been visited and revisited. But too often it’s the outsider’s view that’s prioritised, and one of plain objectification, as in Terry Richardson’s infamous Terryworld where actors, friends, and sex workers alike are framed in terms of unapologetic exploitation. Or else sex worker’s experiences’ are distilled into purely political statements, as in the more honourable 2020 photography project Absence of Evidence, which sought to highlight the trauma of women trapped within sex work.

Ellie English’s photobook Does Monday Work? avoids these tropes altogether, and does so by being entirely, and proudly, autobiographical. Ellie’s work has long been dedicated to documenting her everyday life and here she turns her attention to her working life as a full-service sex worker. “Sex work has changed me in complicated ways,” reads a plastic card hidden inside the book’s copyright pull-out. “I’ve been hardened by it, yet also softened. At times I’ve been exploited & mistreated, at others I couldn’t have loved my job more.” The photographer’s statement is followed by links to sex worker advocacy groups such as SWARM Collective, but the collection is only political in so far as it is so deeply personal.

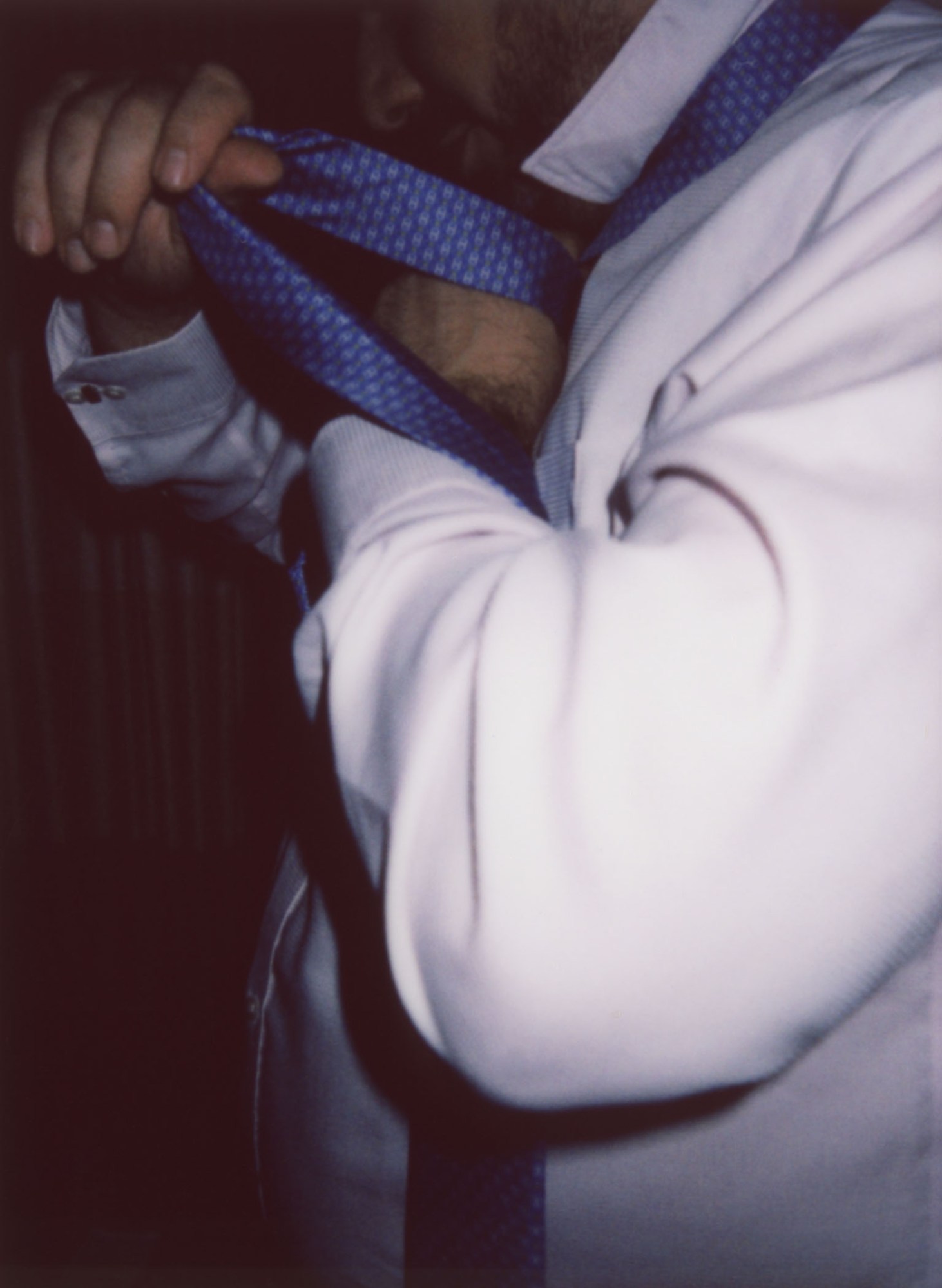

“I wanted to capture moments that meant something to me,” Ellie says when we sit down to speak in a bar near London Fields. “That was the biggest challenge, finding those small details, those things that might seem, actually, really boring, but that speak to something bigger or more significant.” The photographs include shots of ugly carpets in chain hotels, curtains with evening light streaming in, ordinary armchairs, bedspreads. In one shot, a single coat hanger hangs inside an empty wardrobe. These are images that might not mean anything apart from to the person who took them. Some of them appear almost accidental — not unlike the blooper shots you’d find on a disposable camera from a holiday. Others evoke the odd feeling of a half-forgotten memory; an image that sticks in your mind but you’re not sure why.

“There are loads of photographs, and loads of photographs of sex workers, where it’s just all out there, everything’s on show,” Ellie adds. “And they might make great photographs, but it doesn’t give you that much to think about.”

The curation of the book is also closely tied to Ellie’s personal narrative and, she says, was one of the biggest challenges creatively. Many shots that Ellie loved were cut from the book because she simply couldn’t get them to fit, while others surprised her by working their way in. “I wanted to create this feeling of not knowing what might come next. Of walking down corridors, hotel corridors, from one room to the next, one place to the next, to another man. And not always knowing what that might mean.”

Ellie explains that she identifies more as an artist than a photographer, and doesn’t relate much to the elaborate set-ups and fiddly technicality of a lot of photographic practice. “I use a FujiFilm Instax. That’s it. That’s my equipment,” she laughs.

Despite loving the physicality of instant photography, the way the images can become marked, and changed, by their travels through the world, there’s also a practical element to working this way. Some of her photographs are of consenting clients. By using instant photography, she can give them peace of mind. “I can show them the image there and then,” she says. “If they want to, they can take it and keep it. There have been some images I really loved that the client chose to keep. I have to respect that.”

By photographing clients, Ellie has also been able to shift the gaze. “Photographs about sex work are almost always about looking at sex workers,” she says. “I wanted to try a different approach, a different way of looking at things.” The conversations with her clients, she says, weren’t all that complicated. “I kind of knew who would be okay with it and who wouldn’t. Those who would never be okay with this, I didn’t even raise the subject. But, of course, I promised total anonymity, and they could see the images.”

Alongside the mundanity captured here are moments of real intimacy. Of one of the photographs in the collection, Ellie writes: “‘London, February 2019’ shows myself and a client kissing. It’s challenging in many ways, unexpectedly tender and gentle, yet causing an uncomfortableness through its direct honesty. It’s confrontational, yet avoids being pure spectacle. Although now one of my favourite images, I was initially unsure whether it was one I was yet ready to share.”

Ellie’s book launched at the Photo Book Cafe back in May. “That night was the first time I went home with money in my pocket from my art,” she tells me. So what about photographers who choose sex workers as their subjects, who look in from the outside? “I just feel that it’s not really their place.”

Speaking to Ellie, she is consistently hesitant to label a direct goal for her photography, or to pinpoint how (or even if) it has influenced her feelings about sex work. Like her previous photography, which documents microcosmic moments from her life, in this collection Ellie seems to be striving for something creatively that is very simple but also very difficult to pin down: the tiny, ordinary, mundane moments that stay with us.

The legitimisation of sex work as just real, ordinary, work, is still not happening enough. Even less often is the story of sex work being told by sex workers themselves. Ellie’s photographs show sex work as work — everyday and sometimes boring, but for that just another part of life.