In the first week of lockdown, we turned to musicians for comfort. Dua Lipa submitted Future Nostalgia, Justin Bieber responded with the aptly titled Work From Home EP. But it was Machine Gun Kelly whose offering was most unexpected. The rapper, then best known for his high profile partnerships (and beefs), recruited long-time collaborator Travis Barker for a Zoom-recorded cover of Paramore’s highest-charting hit, “Misery Business.” “I swear punk rock is gonna make a comeback,” reads a top comment.

By then, it already had. MGK had teased an unprecedented pop-punk pivot with two well-received singles, and panda-eyed Yungblud had already entered mainstream rotation in early 2019 with an emo-tinged Halsey collaboration, while bands like Movements and Knuckle Puck had shown commitment to delivering Y2K nostalgia for years prior. While an emo Renaissance was in incubation well prior to quarantine, it seems our sudden bedroom confinement propelled a collective regression to our adolescent angst. When “Emo challenges” began to proliferate TikTok — rainbow-haired users measuring their “brokenness” by how many emo-era tracks they could recall — it seemed the aesthetics and sonics of Myspace-era music had penetrated every corner of the Internet. Among those who predicted the return was self-styled punk-pop heroine, Avril Lavigne.

“Trends come and go, but history does tend to repeat itself,” Avril says. “I think a lot of people have been having similar feelings of rebellion, but also people are more open and honest about their emotions and mental health, so I think the rawness in the emo music that we’re hearing today is really relatable for so many.”

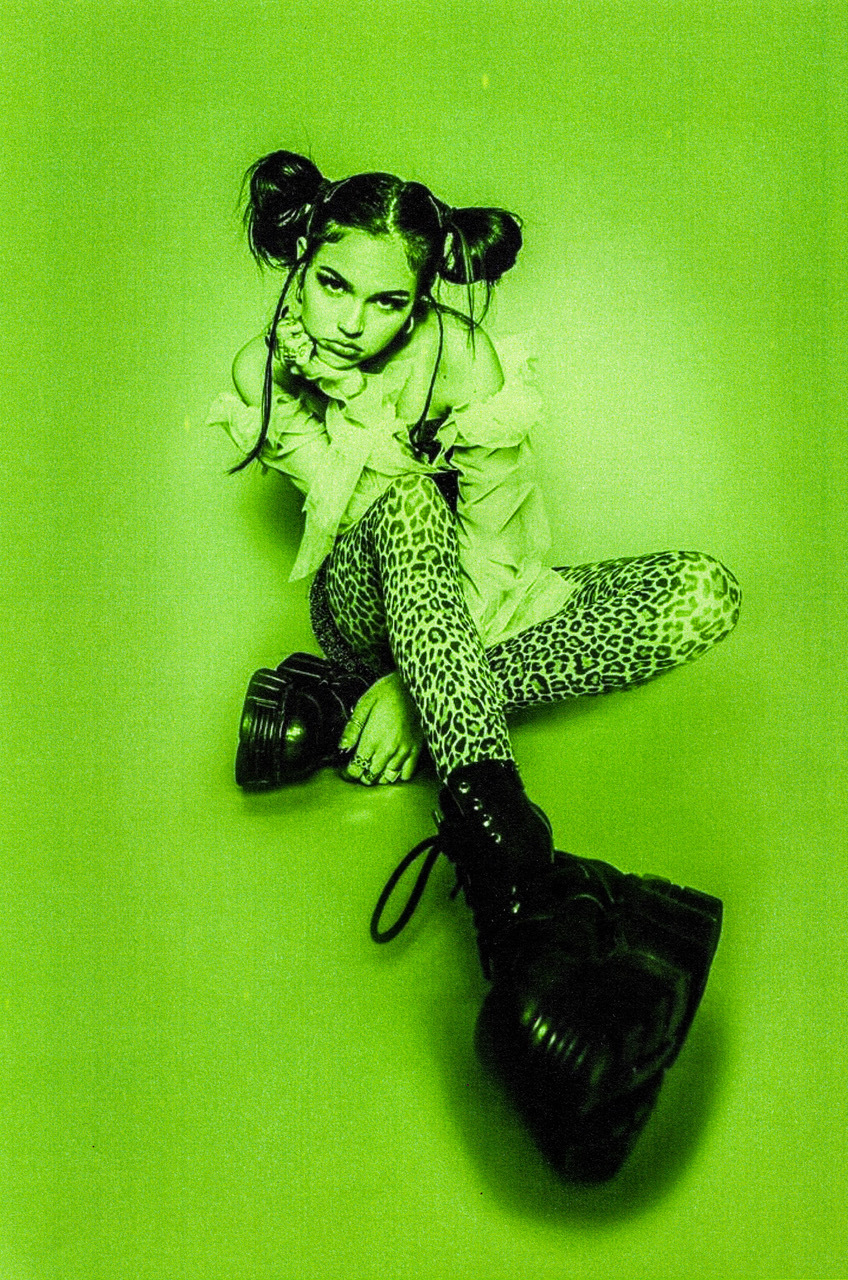

It’s this relatability that’s proving a golden ticket for rising artists. Olivia Rodrigo’s debut album SOUR and explosive sophomore single “deja vu” furthered her agenda to become the mouthpiece for all women scorned. It took little time for critics to muse that Olivia was resurfacing high school melodrama with Y2K references on “good 4 u,” with the track’s explosive hook and Petra Collins-directed music video, and even less for fans to fuse the track with “Misery Business.” Then there’s Willow Smith, who recruited Travis Barker to bemoan fake friends like it’s 2006 all over again on her latest single. But it’s Maggie Lindemann, whose artistry perhaps best embodies the shift. Breaking out with sugary 2016 hit “Pretty Girl” at age 18, Maggie u-turned years and millions of fans later — long brunette locks shorn short and streaked red; nails carved and colored black. The 22-year-old’s debut EP, Paranoia, featured emo’s signature suspenseful pre-hooks and crashing choruses. Recklessly abandoning her good girl image, Paranoia was Maggie’s postcard from the dark side.

“I’m so excited just for pop-punk to be embraced again,” Maggie reveals. “I grew up finding so much comfort in pop-punk and always dreaming and begging to go to Warped [Tour]. So now that I am actually in it, I’m excited to give people that same feeling of excitement.”

For Maggie, the project was testament to her evolution as an artist as well as freedom from “playing the character” of the pretty girl. Foremost, it was an opportunity to pay homage to her favorite artists. Sleeping with Sirens and Paramore were omnipotent influencers over Maggie’s creative choices, but she took her style cues from Avril. While her sartorial impact in the early 00s was undeniable, the fact that Avril’s style — skinny ties, cargo pants and dip-dyed hair — endured for two decades is remarkable. After all, Maggie would have been three years old when “Complicated” was released.

“I was definitely aware that I was doing something different,” Avril explains. “I realized pretty quickly that the way I dressed was making an impact far bigger than I was.”

Chase Hudson, better known now mononymously as LILHUDDY, was born the month prior to Avril Lavigne’s seminal debut record, Let Go. A founding member of the content creation epicenter Hype House, Chase played no small part in catalyzing the catapult of Addison Rae and the D’Amelio sisters, while becoming a TikTok teen dream in his own right. While the 18-year-old might have rested on his Tigerbeat pull-out poster appeal, Chase instead opted for a darker direction. Archiving his cleaner-cut posts on Instagram, Chase recently revealed the studded, piercing-adorned, soft-goth LILHUDDY and his first single as solo artist: a nu-wave emo offering titled “The Eulogy of You and Me.”

“It made me realise a lot more of who I am,” Chase shares of his affinity for emo pop-punk. “I found myself personally a lot more through music… It makes me feel the most alive. The real instruments give me a much better flow than any 808 placed on a track does.”

While “The Eulogy of You and Me” is likely written to be more accessible to Chase’s young fanbase than the output of the entertainer’s own favorite artists, metal-pop band Pierce the Veil, it’s a strong jump-off point for LILHUDDY — who’s no doubt destined to become one of the more front-facing leaders of the latest emo wave.

“It will hit everyone like a truck when it starts to become more and more popularized, and I hope it’ll be respected,” he says. “Right now we have a few artists who are pioneering this journey: taking the genre, reviving it and making it so much more. The Internet and social media has helped to build a new community of fans and participants.”

It’s worth noting that when the emo movement recaptured the zeitgeist, not every artist was happy to be under its umbrella. While My Chemical Romance remains at the top of Chase Hudson’s emo/pop-punk band roster — and the band was often grouped alongside innovators Panic! At The Disco, Greenday and Paramore — frontman Gerard Way still actively rejects their ‘emo’ association, denying i-D an interview so as to detach from the term. In 2007, Gerard made his feelings well-known. “I think emo’s a pile of shit,” he told American college website, The Maine Campus. “I think there are bands that we get lumped in with that are considered emo and, by default, that starts to make us emo.”

Emo or otherwise, Avril believes the garage-based bands of the early 00s were among the first to prove music groups didn’t need an “an expensive studio” to create a truly top-class product. Moreover, their homegrown energy and DIY attitude made them feel particularly relatable to their audience. For that reason, Avril believes both the creators and consumers of ‘emo’ music considered it something of a safe haven: where the misunderstood “could feel like they were a part of something.”

“Years later, I can listen to my songs and understand how they could connect deeply and emotionally with people,” Avril says. “I was speaking up in my music. To know other people have been inspired by my music is the biggest gift of all.”

Maggie echoes this sentiment, adding that for her, emo is synonymous with “freedom”: “Feeling like I can express myself how I want through my music, the way I dress, the way I do my makeup, without judgement…”

While Gerard certainly has a point when it comes to the sonic comparability of MCR and their peers, “emo” would come to eclipse its classification as a mere genre to become a concept. Sure, it’s easy to scorn artists with vaguely comparable sounds when they reach widespread popularity all at once, particularly when they’re lauded for — or pride themselves on — their commitment to counterculture. But when the outcasts become the in-crowd, there’s room for a new swell of non-conformist creatives to shape their respective era. You can claim it’s a comeback, or derivative, but you should know better to call it a phase (mom).

“I think the genre has been slept on in the past, or dismissed,” Chase says, “but it needs to be brought back to modern-day culture in whatever form that may be, and I’m willing to fight for it.”