In a contemporary socio-political situation in which safe and “free” social spaces are not only increasingly diminishing in numbers but are capsized by disturbed individuals as sites of brutal mass-murder, it might be more important than ever to remember and assert the importance of them. Around the world, the nightclub continues to be a refuge for youth, a space of tolerance and joy that encourages the performative experimentation of identities.

While music is generally considered the centre of nightlife culture, the dancefloor is equally a catalyst for the visual and performing arts, political and social protest, literature and fashion. The last 100 years of partying have left us with a rich but often intangible history, often oral and ephemeral, and as conservative politics and urban councils continue to threaten the freedom that makes nightclubs so important, this is the history we must revisit.

Energy Flash, a vast multi-disciplinary exhibition opening this week at the H MKU Museum in Antwerp, sets out to materialise in an institution something as immaterial and non-institutional as raving. At the museum British curator Nav Haq tells the story of the rise and fall of European rave in the 80s and 90s through a vast visual and sonic archive. It tells the story of rave not simply through music and documentary images, but through the visual and artistic legacy in spawned, visual arts, music videos, photography, magazines, fashion, and even legal legislation are included in this inquiry into understanding the aesthetic, political and socio-economic significance of what it meant to be partying in Europe in the 80s and 90s.

Rave culture was arguably Europe’s last big youth movement: a phenomenon that penetrated every larger city and town, and drawing in those from the suburbs of them, summoning its disillusioned youth around a new electronic music experience, from Ibiza to Manchester to Moscow.

Undoubtedly, the 80s were a decade of profound changes in society. The Reagan-Thatcher years gave birth to full-blown neoliberalism in England, that changed the make-up of our society for ever. But the 80s was a decade that also saw the emergence of institutionalised multiculturalism, the end of the Soviet Union, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the beginning of the internet. All of this was encapsulated in the rave experience in some way or other as a movement that believed in autonomy, self-practice, and experimentation—both in music and in new forms of living and socialising that emerged from it, and which had as much of an impact on our youth culture as punk did before it.

80s rave is most often narrated as having Great Britain as its epicentre, not least because of its enthusiastic self-documentation. i-D had a huge following amongst ravers, and was, from its birth in 1980, devoted to portraying and reflecting on the transgressive attitude of a wave of British youth culture that emerged at night in a country living through a deep national recession—often in collaboration with the young photographer Wolfgang Tillmans, who began his career capturing the kids from the scene that surrounded him in London. Nick Knight, Simon Fluery, Edward Enninful all captured the spirit in colourful optimistic editorials.

Outside of London Steve Beckett and Rob Mitchell founded the legendary WARP Records in Sheffield, a label who would release some of the most important tracks of the era by Aphex Twin, LFO, Autechre and the Orb. In Manchester, New Order’s proto-raving electronic New Wave music led to the opening of the fabled nightclub The Haçienda, which became the high temple of acid house for a decade and a half.

As the exhibition attests, even famed, serious artists like Andreas Gursky ventured to the UK to document the unreasonably massive ‘smiley raves’ that were everywhere at the time. An image he captured in 1995, Union Rave, sold for £150,000 at auction in 2013. Going deeper though was Rineke Dijkstra, whose anthropological study of youth in her video work The Buzz Club, Liverpool, UK, from 1996, involved installing a temporary photo studio in the middle of a rave and asking ravers to simply “be” in front of the camera (some subjects smoke their cigarette unaffectedly, while others, responding to the soft house beat in the background and break out in dance). Dijkstra examines the complex period of adolescence, self-expression, and the tribalistic approach to social life inside the rave experience.

Thankfully, the exhibition expands the history of raving beyond British anti-Thatcherism to include continental Europe, especially in the Low Countries. In Belgium, the ‘new beat’ genre emerged in the mid-80s, a mix of hard edged European electronics and the house sounds of America. Combined with the rise of Dutch gabber this lead to a full-blown underground scene erupting the countries, and becoming the epicentre for early hardcore.

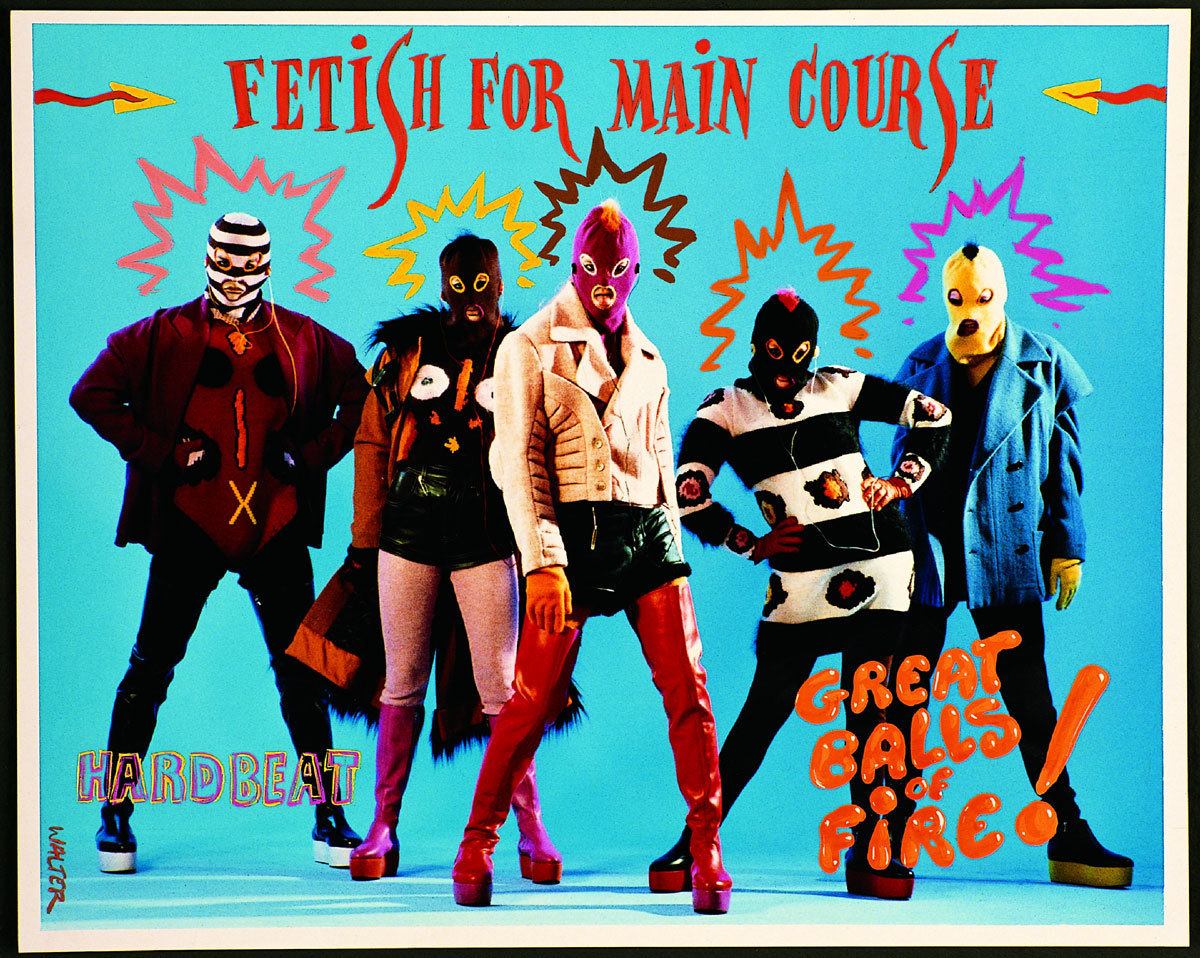

Drawn to the movement’s emphasis on tolerance, freedom of expression, and anti-normalcy, Antwerp Six designer Walter van Beirendonck designed his autumn/winter 89 Hard Beat collection based on New Beat, using cassettes with music by Belgian group Arbeid Adelt as show invitations—the following year, his multi-colored bike shirts from the collection became a hit amongst ravers due to their comfortable feel and edgy appearance. In Ghent, R&S Records had been running since 1984, ensuring releases by the likes of Jaydee, Capricorn, Sun Electric, and most notably, Aphex Twin. Surprisingly, Belgium was also the centre of Ecstasy production in the 80s and 90s, in the Limburg region bordering Amsterdam. These were all things formed Walter van Beirendonck protegee Raf Simons would unite together when he emerged with his first collection in 95. Throughout his career he has often worked in references to New Beat and the subcultural tribes of the era throughout his collections.

Further to the east, in the newly united Berlin, artist Daniel Pflumm and electronic musician Klais Kotai established nightclub Elektro in 1992, on the former premise of an electronics store. As a subversive and spontaneous artistic gesture, later to become his trademark, Pflumm appropriated the store’s illuminated sign and made it the emblem of his club.

Because, as the H MKU exhibition attests, raving was as visual a movement as much as it was a musical one. Just as techno music encouraged experimenting with sampling, the 80s saw artists fully embracing montage and appropriation as artistic strategies. Relational aesthetics began understanding all spaces of society as potential sites for art, from the dancefloor to the gallery space. Not a lot of people know that famous video artist George Barker produced the music video for Jaydee’s classic anthem Plastic Dreams. In the 10-minute video, a sensually dancing silhouette hovers above the abstract fluorescent flower visuals which were later to define his career. Factory, the record label who ran the Hacienda, spent a great deal of time experimenting with the record cover as an artistic medium, often with Peter Saville.

So experimental did they get that for New Order’s Blue Monday they ended up losing money every time they sold a copy due to the high cost of the intricately graphic record sleeve designed to resemble a 5¼” floppy disk. Unfortunately for Factory the track became the biggest-selling 12″ single of all time.

The accelerating speed of technological development was evident in rave music and in its aesthetics, as exemplified in the work of British video and music group Psychic TV (Genesis P-Orridge and Peter Christopherson): combined with the desire to visualise the abstract electronic language of techno and acid house, rave culture reinvigorated cybernetics, and laid the free-spirited foundation for net.art as a highly politicised form of art in search for autonomy and self-expression online. Alexandra Domanovic’s mesmerising 2010 video work 19:30, best encapsulates this, as a collaborative audio-visual art project in which she asked electronic musicians to rework archive news footage about raving in the former Yugoslavia into new musical tracks (the rave movement made an equally strong impact in Eastern Europe and the Balkan countries, albeit with a slight delay). The intersectionality of dance culture, cultural exportation, globalisation and regional political conflict provides one of the most poignant prisms of reading the history of Europe’s youth culture.

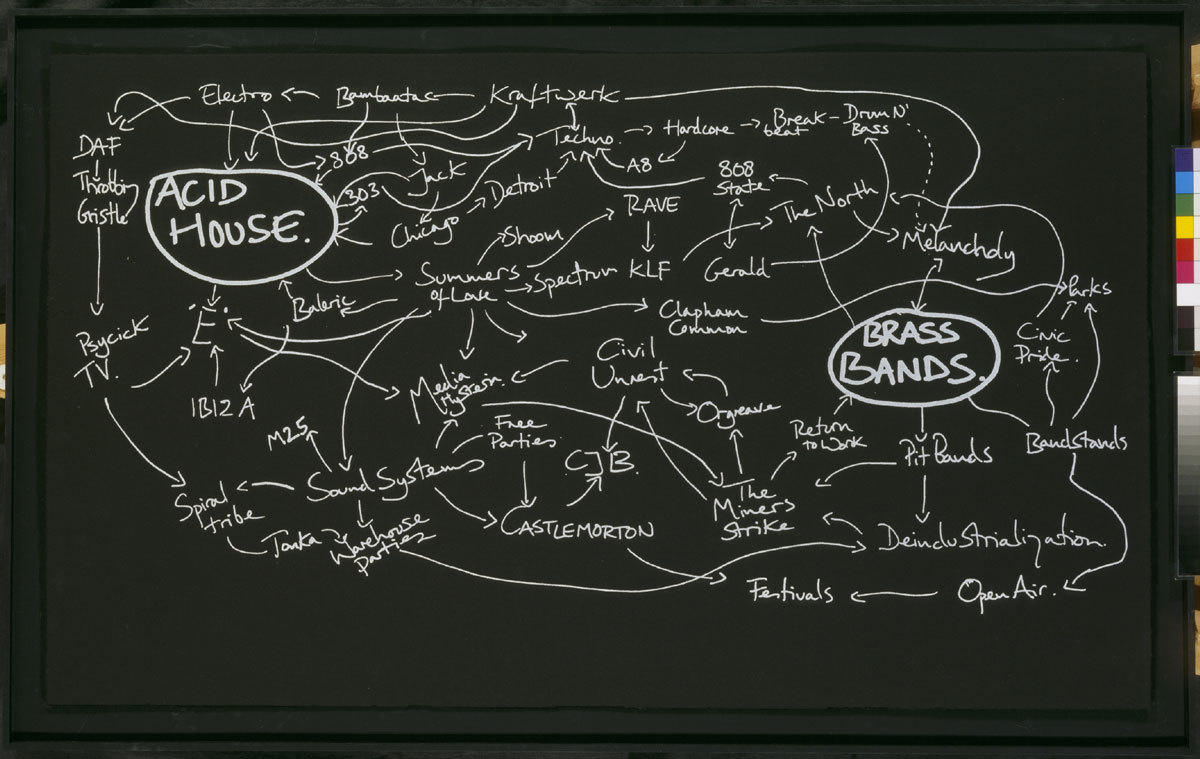

Even today, rave and nightclubbing function as a discursive and structural thematic for many artists. In the seminal mural The History of the World, perhaps better known as Acid Brass, Jeremy Deller linked the musical, social and socio-economic conditions of recession-era post-industrial society with a surprising simplicity, underlying the all-encompassing implications rave had for larger society. Spanish artist Irene de Andrés’ work balanced the shows frantic energy with an ambient and meditative piece about her native Ibiza, where she grew up as the island became gentrified as the ultimate mecca for rave in the early 90s. Interested in leisure, tourism and the movement of such economies, Andrés video pieces document Ibiza’s many abandoned nightclubs. Over an ambient techno beat, she reconstructs the parties of the iconic Festival Club, which formed in a derelict bull fighting arena on the island after a building project for a club was rejected due its close proximity to a precious biodiversity area. For today’s hyper-commercialised club industry, raving of the old school already seems an archaeological phenomenon.

Raving was a fundamentally invasive force that transgressed social conventions, and naturally, its immense sociopolitical impact resulted in its abrupt termination. Moral panic was spreading as raves and E grew in popularity, turning the sight of a thousand kids dancing in a field into an actual revolutionary force that might be able to challenge the prevailing neoconservative ideas at the time. Spearheaded by the Thatcher government, the UK was the first to criminalise rave as they, rather incredibly, banned parties with music (quoted from the public legislation) “wholly or predominantly characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats.” France followed shortly after, and in 2002, Joe Biden and potentially future president Hillary Clinton terminated rave culture in the US as they implemented the so-called “RAVE Act” — RAVE functioning as an ironic acronym for “Reducing Americans’ Vulnerability to Ecstasy.” Without a doubt, directly criminalising a particular form of music proves the revolutionary nature of music—and the arts as a whole.

Regrettably, with the exhibition’s diverse lines of inquiry into rave, one essential history was not adequately addressed. The queer origins of not just techno and house music, but of the modern dance floor as such, have been accounted for by several people—but remains an unexplored history, particularly in the aggressively “straight-washed” EDM music-culture of modern day America. 1989, the “second summer of love” and the height of raving, was also the year when the AIDS crisis fully erupted, an epidemic killing youth in all European and American cities—many of the founders of rave-culture included. It is furthermore obvious that the free, hedonistic, transformative “third space” that rave culture proposes is built on an imagined autonomous spatiality that queers have fought for for decades.

Immaterial histories are immensely important, but often incredibly difficult to inscribe in our collective cultural memory (Internet artist Cory Arcangel’s archiving of a deceased DJ’s record collection in his interactive installation The AUDMCRS (2011) is hopelessly nostalgic and melancholic in its re-engagement with outdated technologies). Sadly, such archival challenges often lead to cultural amnesia, a kind of amnesia that allows the continuous undermining of rave’s culture’s importance today. The exhibition Energy Flash makes a striking effort to remember this history and communicate it to a younger generation that perhaps feels estranged to today’s straight, restricted, monitored and hyper-commercial clubbing experience. Walking amidst acid house tunes during the opening night, the only thing that was missing was, of course, the partying (although original Kraftwerk member Wolfgang Flür energised visitors with his hedonistic opening speech about the uses of Ecstasy). It felt significant and powerful that these histories, mostly associated and criminalised as “low-culture,” are recognised as important, and finds a home in our public institutions. One can only hope that we never forget the power of rave.

Energy Flash is open until 25 September at H MKA, Antwerp

Credits

Text Jeppe Ugelvig