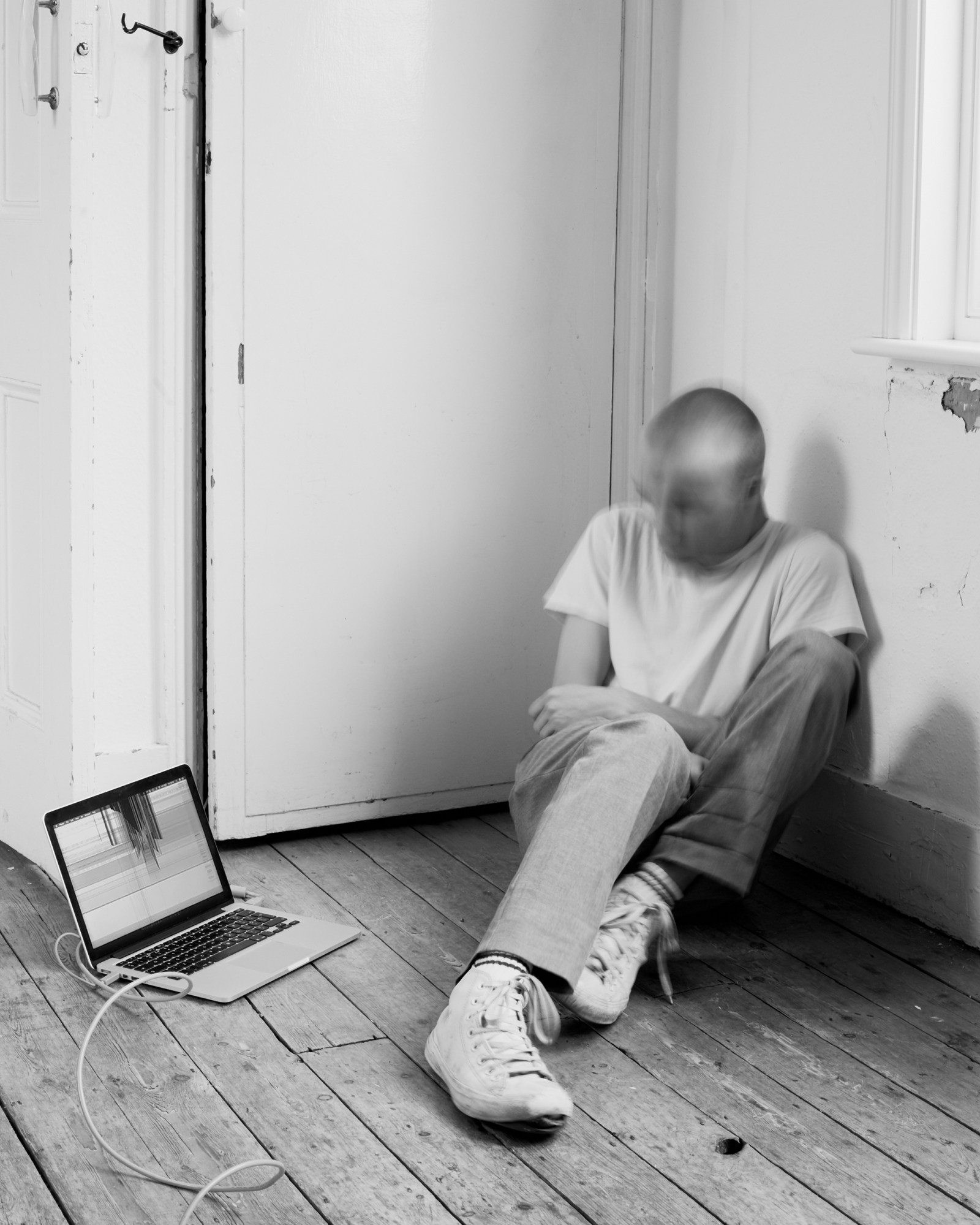

Photographer Ethan Hart was never really one for self-portraiture prior to lockdown, preferring to focus on other people in his work. That said, the constraints of the past few months meant that he could take the opportunity to train his lens on himself. As he took to experimenting with the medium for the first time, at home in his North London apartment, he was struck by the thought of focussing on an aspect of his everyday life that’s been with him since childhood: his experience of Tourette syndrome. “I actually started taking self-portraits on a totally unrelated note, but it developed into a documentation of that, which felt really natural and honest,” he says. “In the back of my mind, I’ve always been really curious as to how I would go about it visually, but I don’t think I would’ve actually done it if it hadn't been for lockdown — I wouldn't really have had the headspace.”

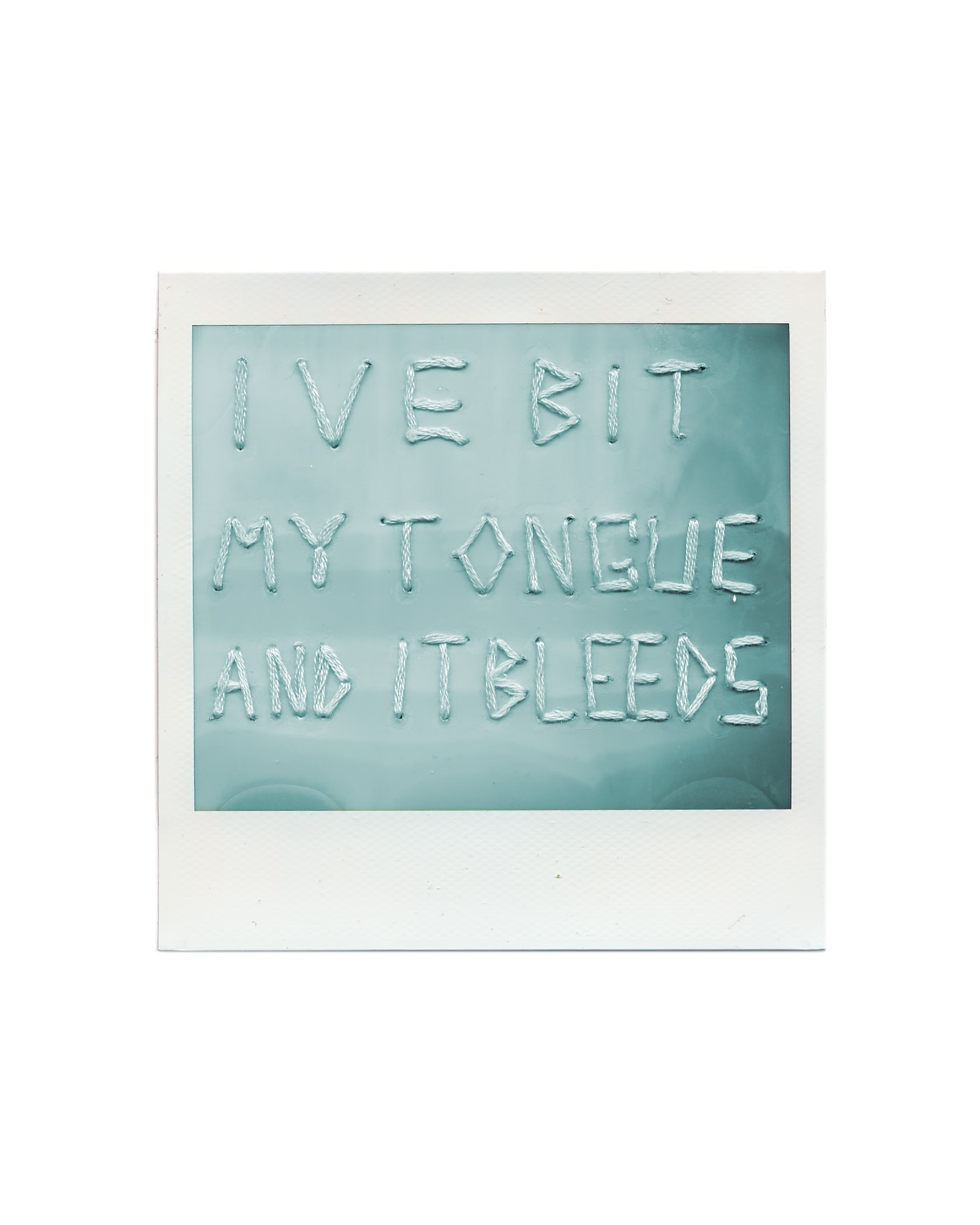

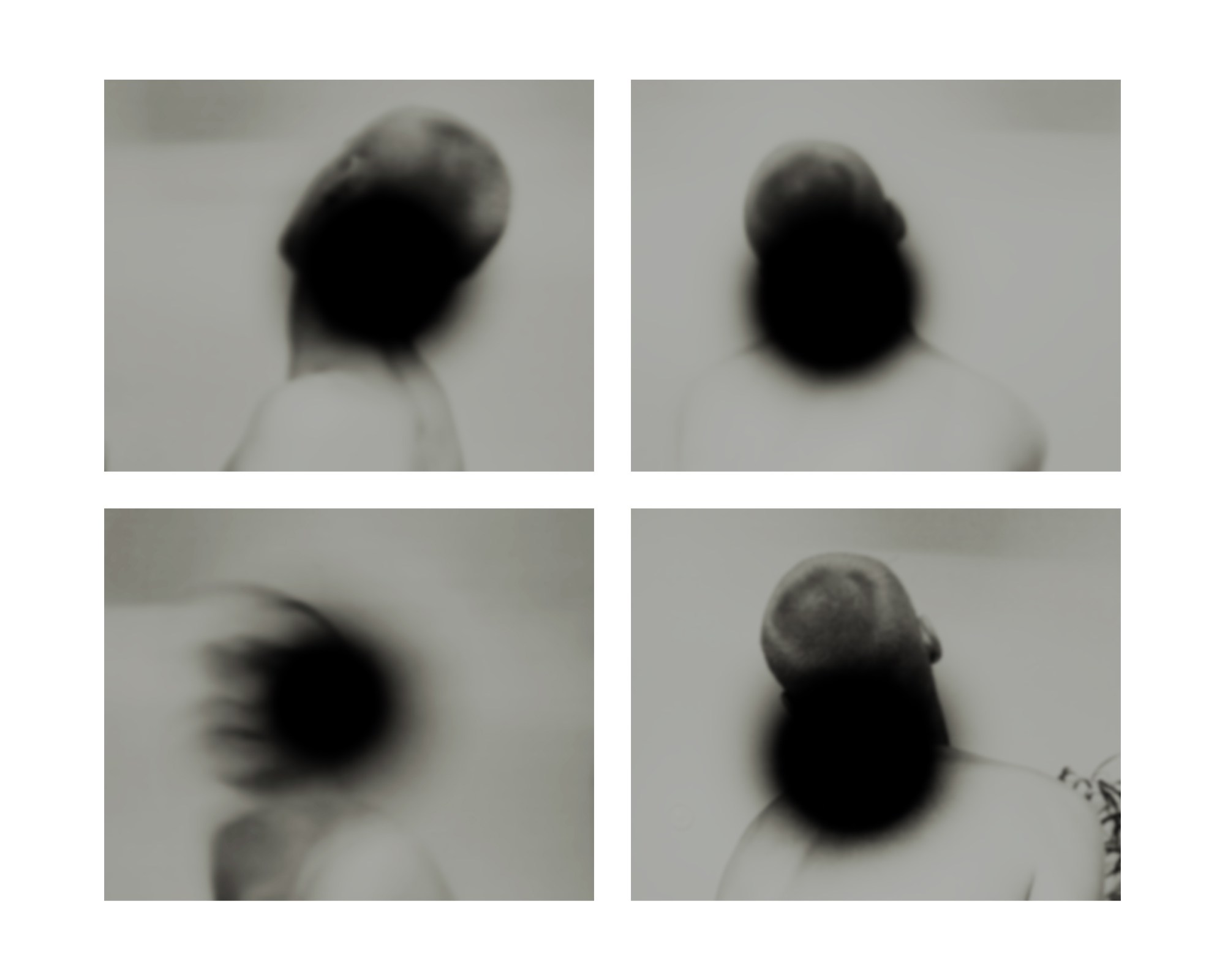

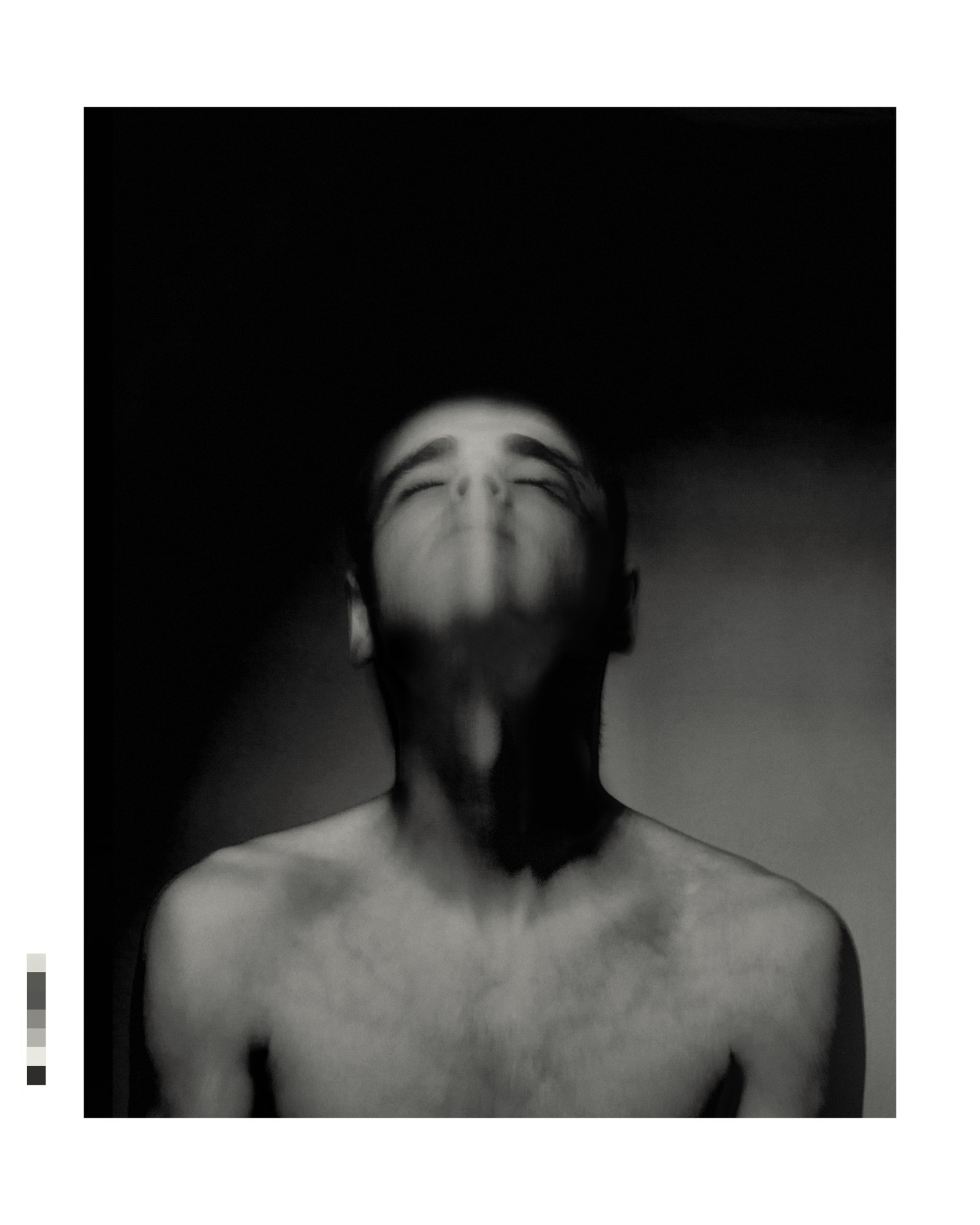

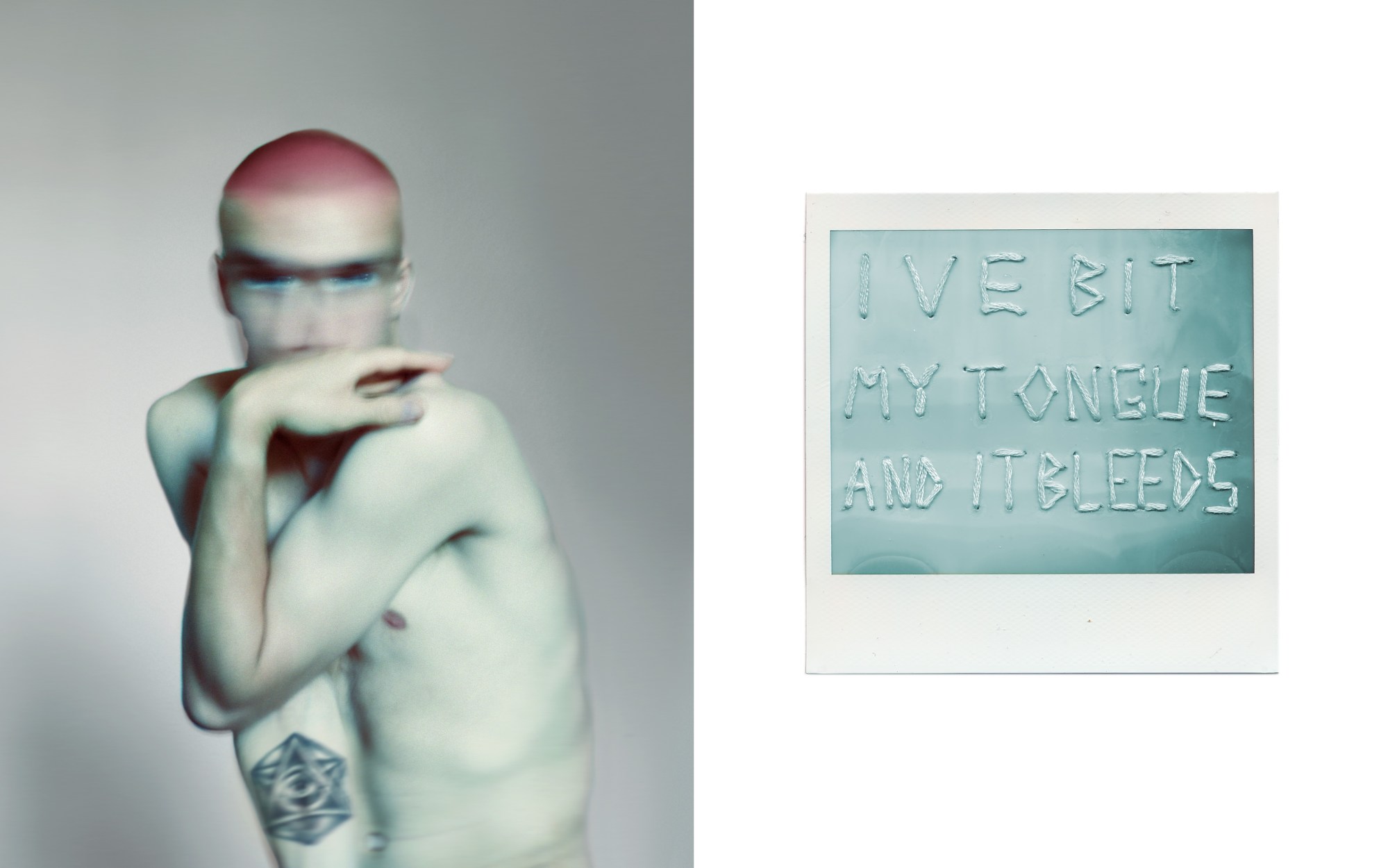

Central to the photographs he’s taken is a duality between the (often physical) pain and frustration Ethan’s Tourette’s causes, and a sense of harmony, acceptance and control. “The way I've always thought about it is that it's like a separate thing from myself. There's who I am and the things I want, and then there's 'it' and what ‘it’ wants, almost like an evil twin telling me what to do,” Ethan explains. “Often, the feeling would want me to do the worst thing in a given situation. For instance, if I'm cooking, I can get an urge to touch a hot pot with my hand. There are certain degrees to which I can control that, obviously, but in the images, that sense of frustration and pain comes through a little. But I also wanted to move forward and have some of the images be more accepting, more focused and controlled. It is all about a balance between those two things, as they come and go in equal regard.”

As for his objective in releasing the photos, he’s most interested in offering a nuanced portrait of what living with Tourette syndrome looks and feels like, thereby helping to dispel widely-held misconceptions surrounding the condition. “When people hear Tourette's, they think of swearing and shouting, and that actually only affects about 5-10% of people that have it,” Ethan says. “I wanted to talk about it in a way that made it more natural, real and understandable. It’s something I battled with a lot as a child when it began, but over the course of my late teenage years, I started to accept and really own it. Now, I think that if I didn't have it, I would feel much less like myself. I want to help people understand that a lot of people do have it and hide it, but that it's something to be proud of and to embrace.”