She doesn’t have a solo show at MoMA or a six figure sales record at Sotheby’s, but Arab-American Sophia Al-Maria is one of the most exciting artists in the world right now. Perhaps its because her vision spans such irreconcilable influences as ancient Bedouin culture and sci-fi, or perhaps it’s because her approach is so multi-disciplinary, that she terrifies as much as fascinates curators. That said, it didn’t stop her winning over the Serpentine’s Hans Ulrich Obrist, who has been championing her work for the past few years. Nor did it stop her reaching audiences with the most innovative project at this year’s Frieze art fair. Inspired by John Carpenter’s film They Live (1988), which considers subliminal messaging, Al-Maria created a tour illuminating UV painted symbols hidden to the naked eye and situated at stations around the fair; the tour was set in an imagined near future, following a series of catastrophic weather events that have wiped out vast swathes of the world’s population.

In the grand scheme of things, Al-Maria seems to say, in light of global warming, waning resources and a failed capitalism, how important is an art fair? And when audiences eventually reach the conclusion of ‘not very’ the whole thing begins to take on a new aspect.

Compare this to the regular stable of Western artists wheeled out to make work in response to discourse that only graduates of the field can appreciate, and you start to see why Al-Maria and fellow artists from the Middle East and of Arabic descent are so important.

Take Iranian artist Monir Shahroudy Farhamanfarmaian, whose compositions immediately bring home the incidental futurism in the principles of ancient Islamic geometry. Despite being active for over five decades, her work attracted as much attention at Frieze as any of the hotly tipped young western artists. Not in spite of its ancient heritage, but because of it: it’s satisfying symmetry; it’s sparkle; it’s sheer scope in its meticulous attention to detail. There’s an art to creating things that look nice that’s been lost in the centuries-long race to out-smart each other.

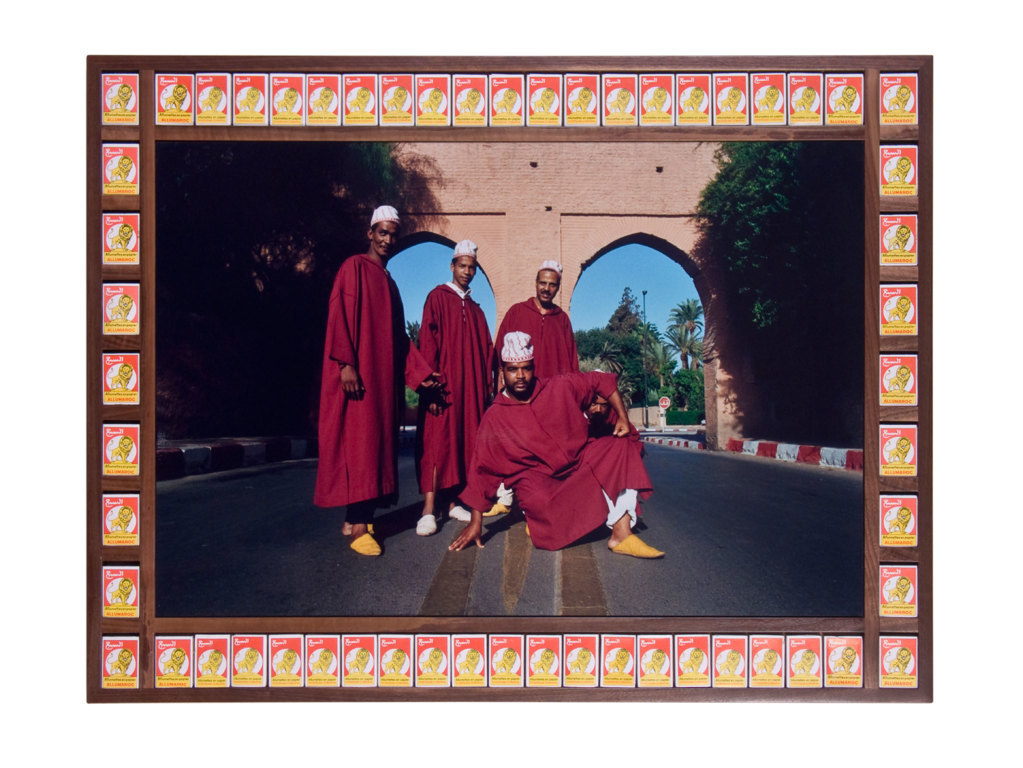

Or Moroccan-born Hassan Hajjaj, whose street photography captures the prevalence of brand insignia throughout North African style. A regular face on the London club scene in the 80s, Hajjaj rose to fame after styling the Andy Wahloo restaurant in Paris – a portmanteau that brings together one of his favourite artists and a Parisian slang term meaning ‘I have nothing’. His work explores brand culture and its trickle down into poorer communities. Often incorporating found objects such as cigarette boxes into the frames of his photo-prints, it immediately attracts, drawing you in with its bold patterns and sublime irony, which perfectly captures the clash of cultures in the age of globalisation.

The work being produced by these artists, who are all represented by the Third Line Gallery in Dubai, speaks a universal language that can be intellectualised if prompted, but is not necessary. Walking into Frieze, Al-Maria’s collaborator and seminal musician Fatima Al-Qadiri’s track ‘Shanzhai’ can be heard echoing down the tent’s temporary corridors. From her 2014 album Asiatisch, the track’s title comes from the Chinese term used to denote counterfeit Western goods and uses a vocalist singing nonsense Mandarin lyrics to the sound of Sinead O’Connor’s ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’. Which is a loaded statement in itself, but taken on face-value makes for a hauntingly beautiful track characteristic of Al Qadiri whose music has always drawn on the landscape of videogames and the virtual reality dreamed up by the hyper-futuristic vision of modern Kuwait, where she grew up.

The track was being played by meta-brand Shenzhai Biennal, the brain child of stylist Avena Gallagher and artists Babak Radboy and Cyril Duval, which I guess is another story but nevertheless plays into a wider narrative, spearheaded by Al-Maria, of prompting audiences to think outside of the traditional, Western art world narrative.

It’s a bold move, and perhaps Al-Maria’s attempts to explore the future are beyond the achievable aims of one artist, but that’s hardly the point. Watching as an army clad in Michael Kors marched through the fair and nodded with thoughtful expressions over the same big-name Western artists, it’s easy to think that the art world is eating itself; yet Al-Maria’s tour saw suit-wearing banker types through to five-year-old children gawping open mouthed and looking at one another for answers. This, you begin to feel, is the role art should be playing.

Nowhere comes in for more scrutiny than the Middle East. Yet one small consolation for intrastate wars, precarious politics and human rights controversies is the magnitude of work produced by artists from the region. Where else apart from Saudi Arabia would you see an internationally renowned artist double up as a serving member of the military, such as in the case of Abdulnasser Gharem? Though I’m reluctant to draw sweeping conclusions and we can only speculate that living under the duress of new wars and rapid regeneration produces more prescient work, one thing remains clear: that if there is a movement capable of dragging the art world away from the possessive clutches of a few PhD art institute grads its that of the Middle East. Where the work looks good and has the gall to speak directly to its audience.

Credits

Text Nathalie Olah

Image Hassan Hajjaj, Daka Marakchia In Red, 2000. Courtesy Third Line Gallery.