New York’s Bond Street stretches only two blocks. It begins on Broadway and ends on the Bowery, bookended by an Equinox (0 Bond) and Drake’s OVO Flagship (54 Bond). Between them: Gene Frankel Theater (24 Bond). For over 60 years, the independent playhouse has hosted the kinds of experimental performances that once incubated downtown. Since 2005, the theater has been under the direction of artist Gail Thacker.

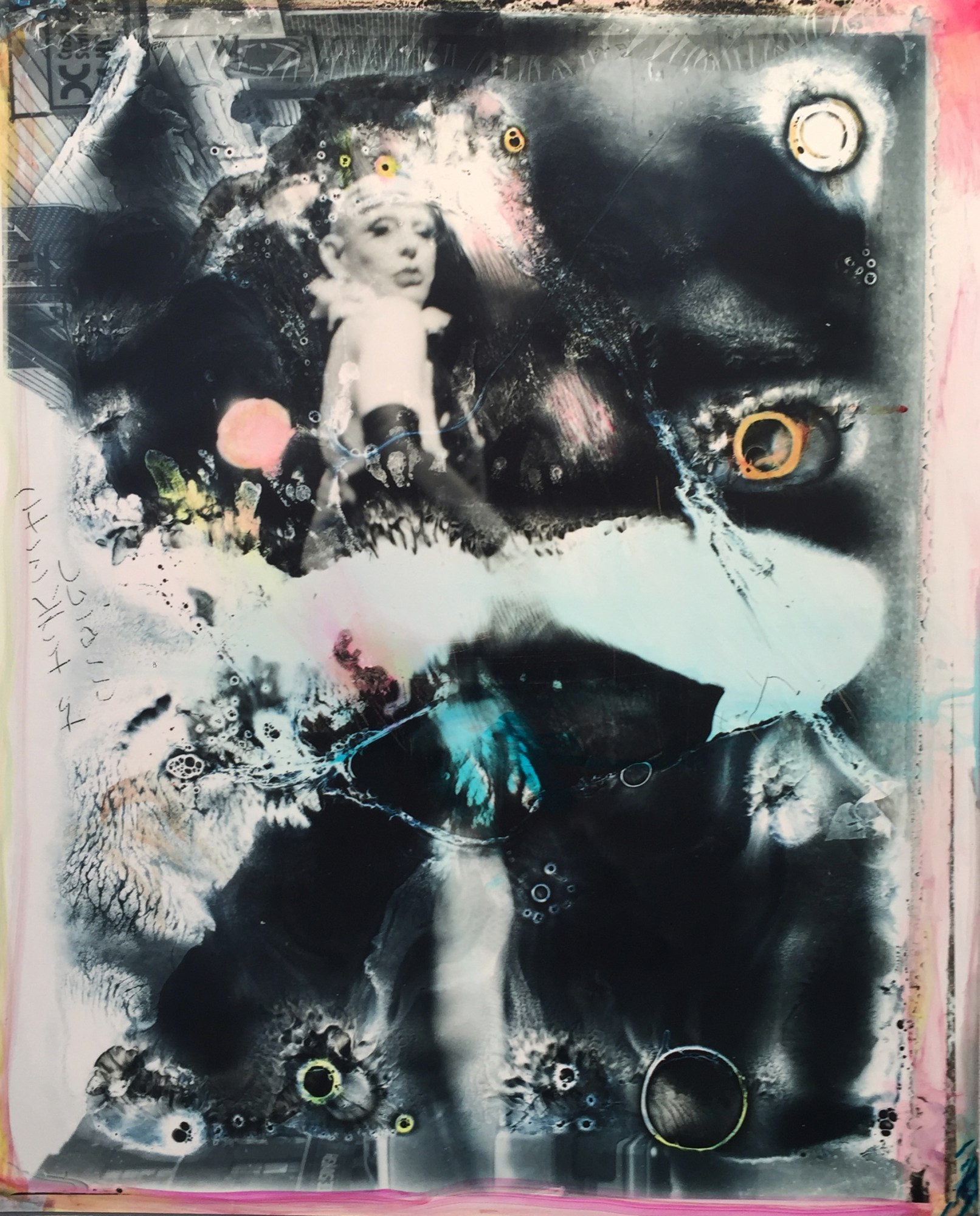

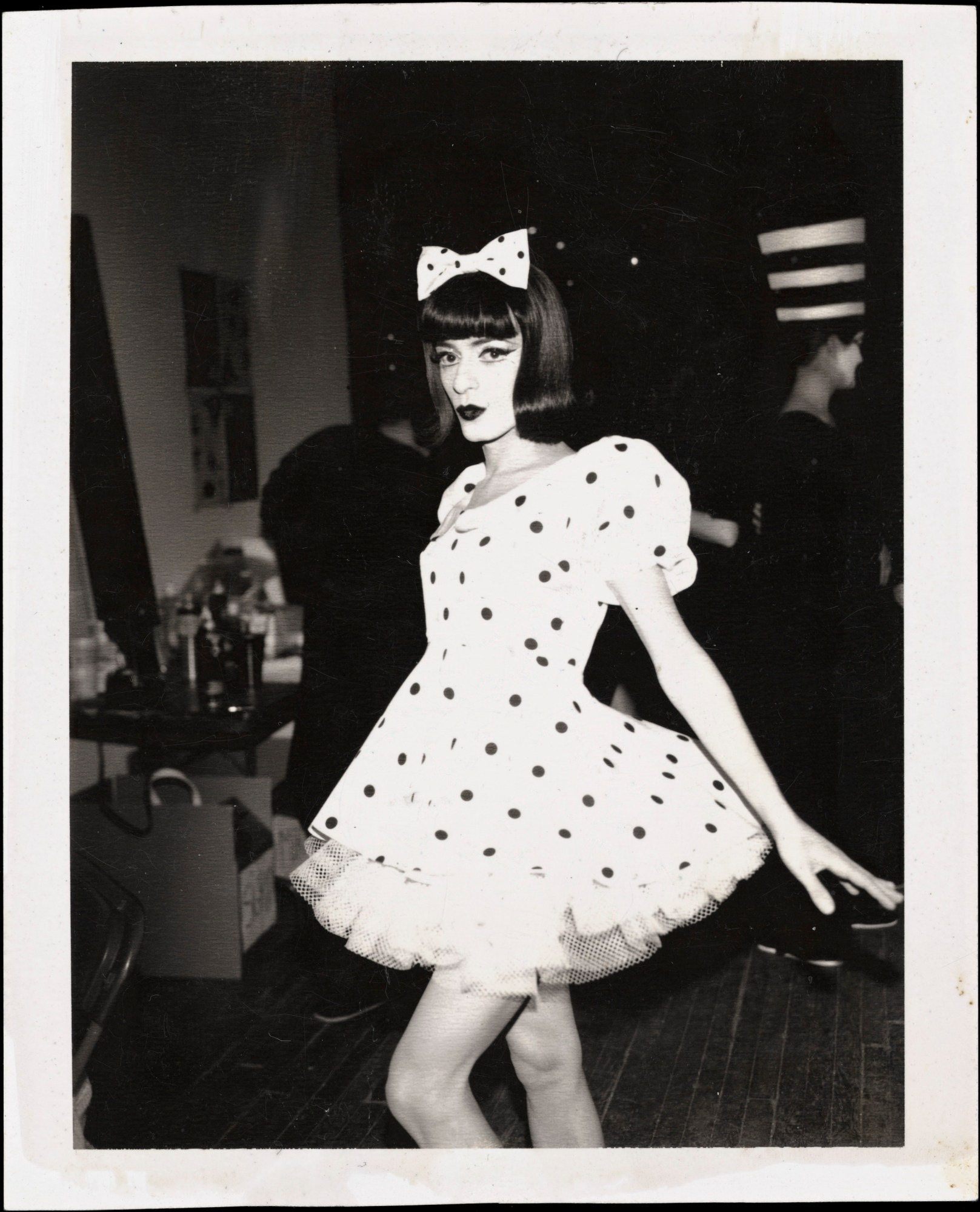

Earlier this month, Thacker opened an exhibition at Daniel Cooney Fine Art on 26th Street in Chelsea. Between the Sun & the Moon collects over three decades of her uniquely manipulated Polaroids. Thacker photographs friends, theatrical collaborators, streets. Then, she wraps up the Polaroids and lets them be. Sometimes in her closet, sometimes under her mattress, sometimes outside. For weeks, for months, for years, even. Each Polaroid is responsive to change and chance. “I see them as living things,” she says.

You can probably find Thacker’s pictures on Bond Street. Photobook paradise Dashwood Books sits across the street from the theater, and Thacker is part of the much-documented Boston School. The influential tribe of artists and photographers (among them Nan Goldin, David Armstrong, Jack Pierson, Mark Morrisroe, Philip-Lorca diCorcia, and Tabboo!) studied at Massachusetts art colleges in the 1970s before relocating to New York.

It’s a somewhat misleading name. While a few Boston School artists took classes together, knew each other socially, or even dated, many others didn’t. Goldin, for example, had already left Boston by the time Thacker transferred to the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. “We’re often put in a group as if we all knew each other and were all in Boston together at the same time. But we weren’t,” Thacker explains. “We overlapped each other as small groups. We all knew each other further down the line, when everyone came to New York.”

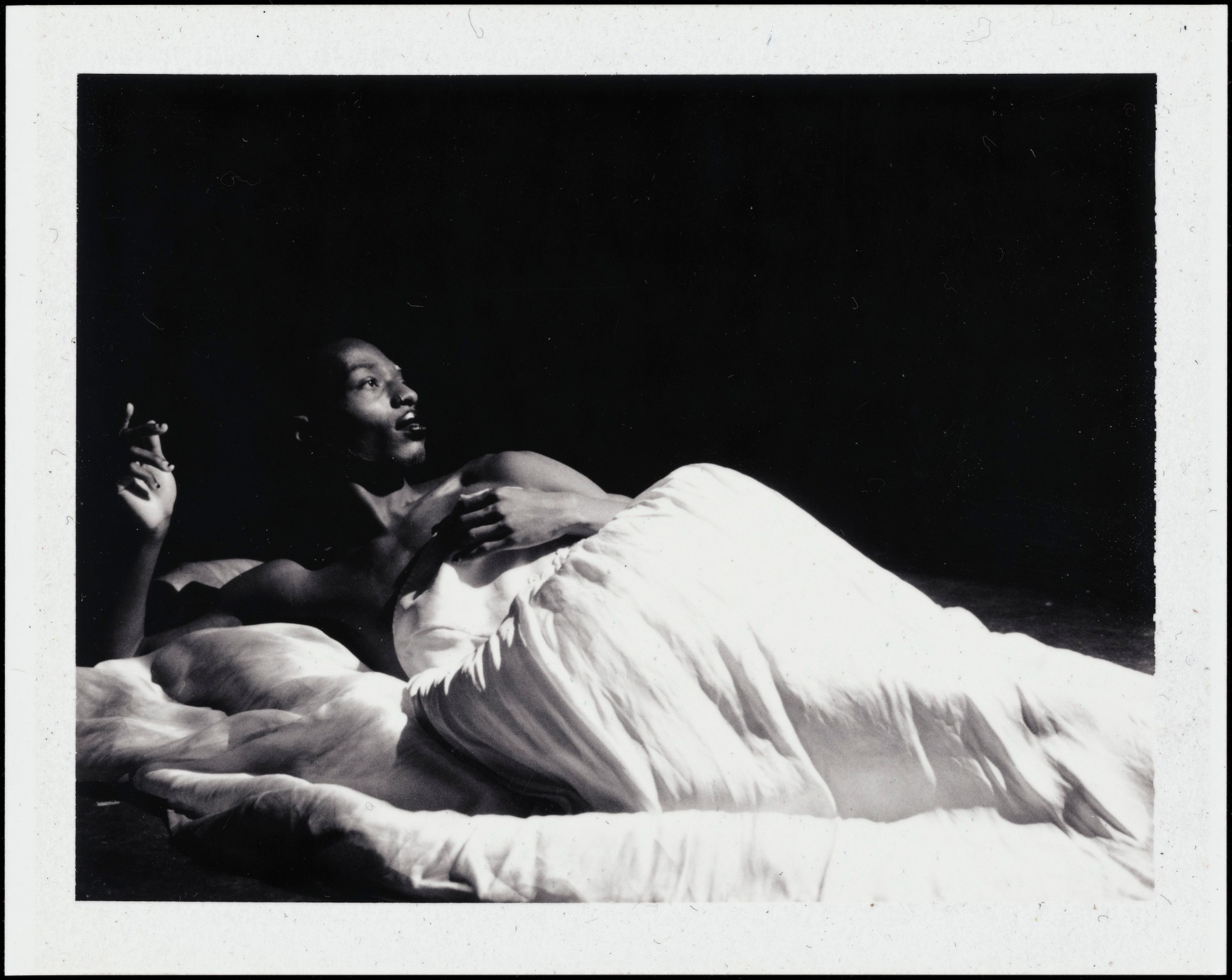

Yet this early Massachusetts mythology has persisted. Perhaps because (however divergent the artists’ practices) much of the group’s work captures community, desire, resourcefulness, obsession, playfulness, sex, experimentation, heartbreak, grief, pain, and love. It is about life, and about death. One of the most important photographs in Thacker’s show is a portrait of Morrisroe — the wild proto-punk she called her best friend — in bed. She made the picture in 1989, shortly before Morrisroe died of AIDS at just 30 years old, with film he gave her.

I spoke with Thacker about meeting Morrisroe for the first time, why she never used to walk down Bond Street, and the magic of manipulating Polaroids.

What drew you to art school?

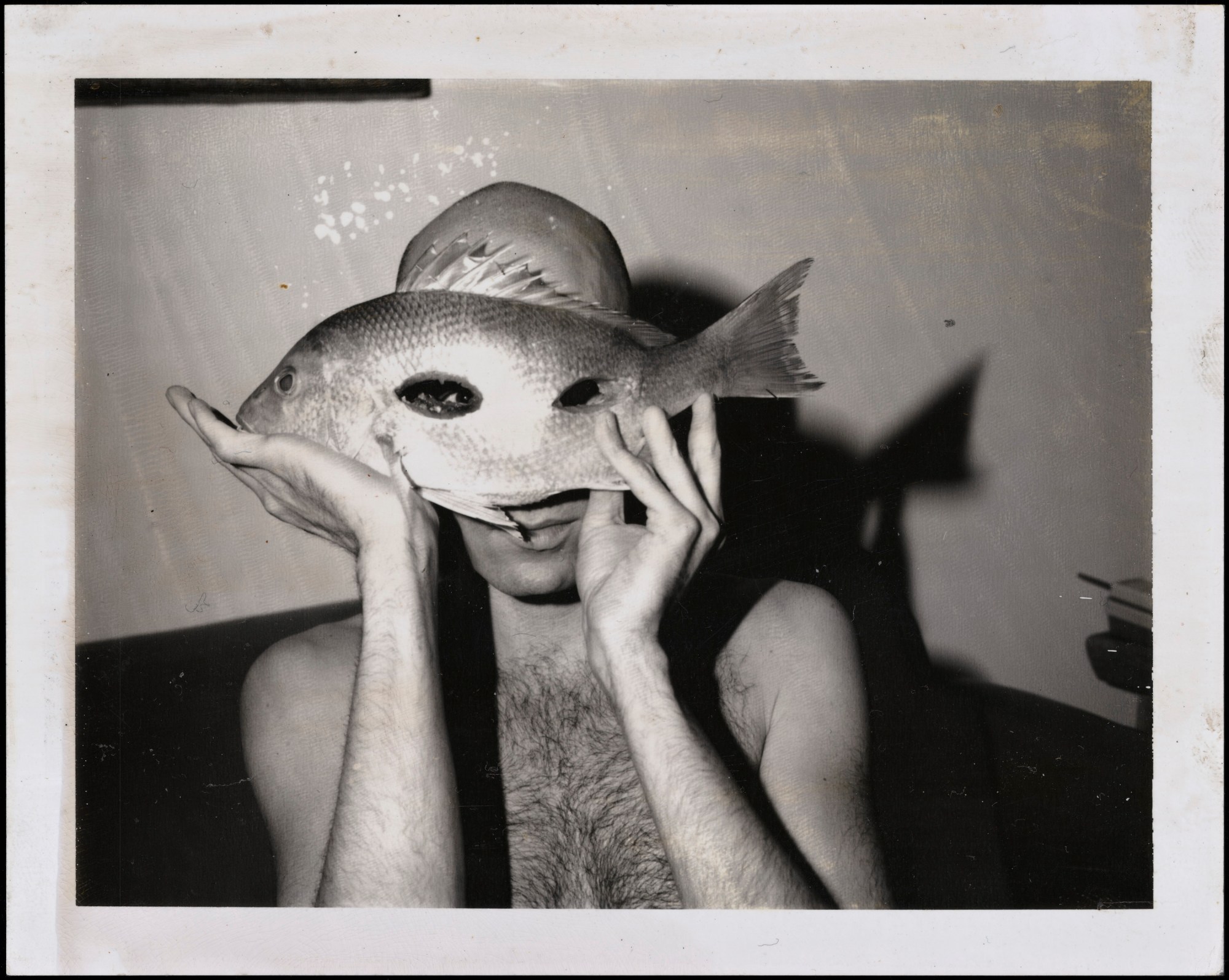

When I graduated high school, I wanted to go to clown school! I applied to Ringling in Florida. But my mother paid me to go to art school! [ Laughs]. It’s so funny, because I run a theater now. It really works with my art, because my work is very theatrical. Once, Hapi Phace, an artist who lives in Massachusetts, asked, “Gail, do you want to be in one of my acts? It’s a car full of clowns.” I said, “ Yes!” So I got to be a clown. I don’t know what would have happened if I went to clown school. I probably would have quit.

You could have been a famous clown.

I could have been!

Were you studying photography at SMFA?

I was studying painting and video. I was just taking photography as a side thing. As we went along, the seed was planted.

Did you meet everyone in school?

I met Mark [Morrisroe] on my very first day at the Museum School in a video class that was taught by Jeff and Jane Hudson, who were in a punk rock group called The Rentals. I transferred from the Atlanta Arts Alliance, and showed a videotape that I made there. It was a tape loop; I actually cut the video and taped it back together. It was this guy chasing a dog around a table. The tape got caught, though. Mark thought it was hysterical and burst out laughing.

That evening, Mark stormed into my apartment with his friend Lynelle White — she was his sidekick and they were inseparable. He started going through my notebooks, pulling my artwork off the wall, laughing. Lynelle pushed me on the bed when I tried to stop them. I was really upset. The next day, I saw Mark in school. He said, “I’m sorrrrry” in his whiney voice. Then, we were friends. Inseparable from that day forward. Mark had a weird way about him when it came to making friends. He left a shit in Nan’s mailbox.

Was there anything to do in Boston?

[ Laughs] Not really. But there were some good clubs. The Rat, Spits, Cantones, where Lou Miami & the Kozmetix used to play. Some people had parties in vacant lots or lofts. But we were just really into doing our art, you know? We wanted to be great artists. We met Pat Hearn about the same time, and started making our own scene. We met this guy, Steve Stain, who was living in a warehouse down at 38 Thayer Street. He had a performance art group, The Stains. It wasn’t punk; it was crazy, screaming, New Wave. We all played and did performance art. Further on down the line, Mark met Jack. Then they started dating, and others, Tabboo!, came into the mix. We just made things happen ourselves. We were playful kids.

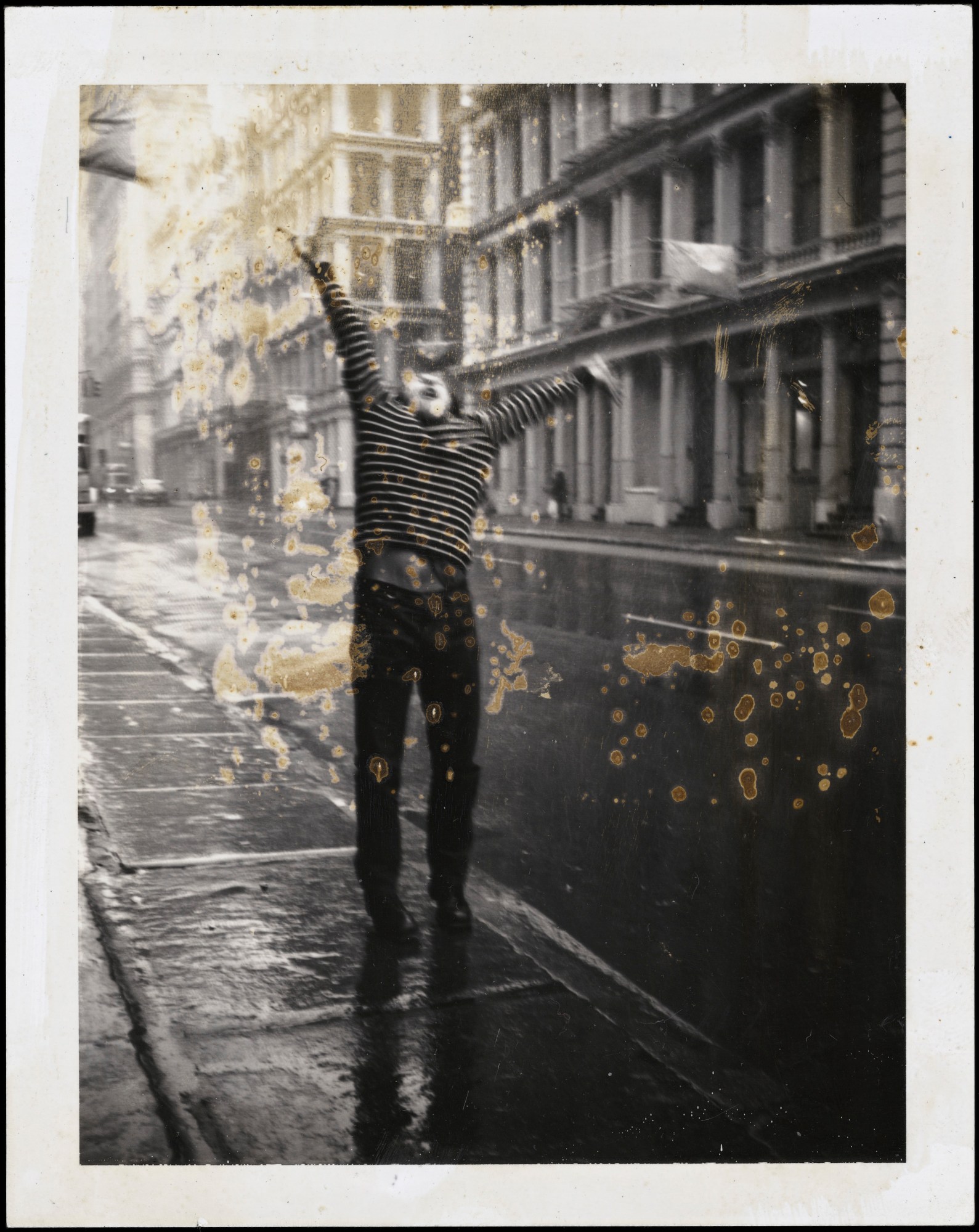

You moved to New York in 1981. What was the city like then?

Gritty. It was unsafe, it was fun, it was just different. You couldn’t walk down certain blocks. If you were walking to CBGB, you did not walk down Bond Street. There was no lighting, prostitutes everywhere, drug addicts, and lots of rats. So you walked down Bleecker. You had to be a bit of a risk-taker to live in New York in the 80s.

You take the risk of living in a dangerous place, but your reward is experiencing some of the best art that’s ever been made.

You’re right, really great art came out of that period. David Wojnarowicz, Peter Hujar. He was overlooked. And so was Mark. He used to whine, “I wanna be faaaamous.” That was his goal, and he was really blatant about it. But really, he was a sweetie. He put this persona on as if he was rough, hollow. He was not, at all. He was a real person, a real artist.

I don’t think you can make work like his and not have a soul.

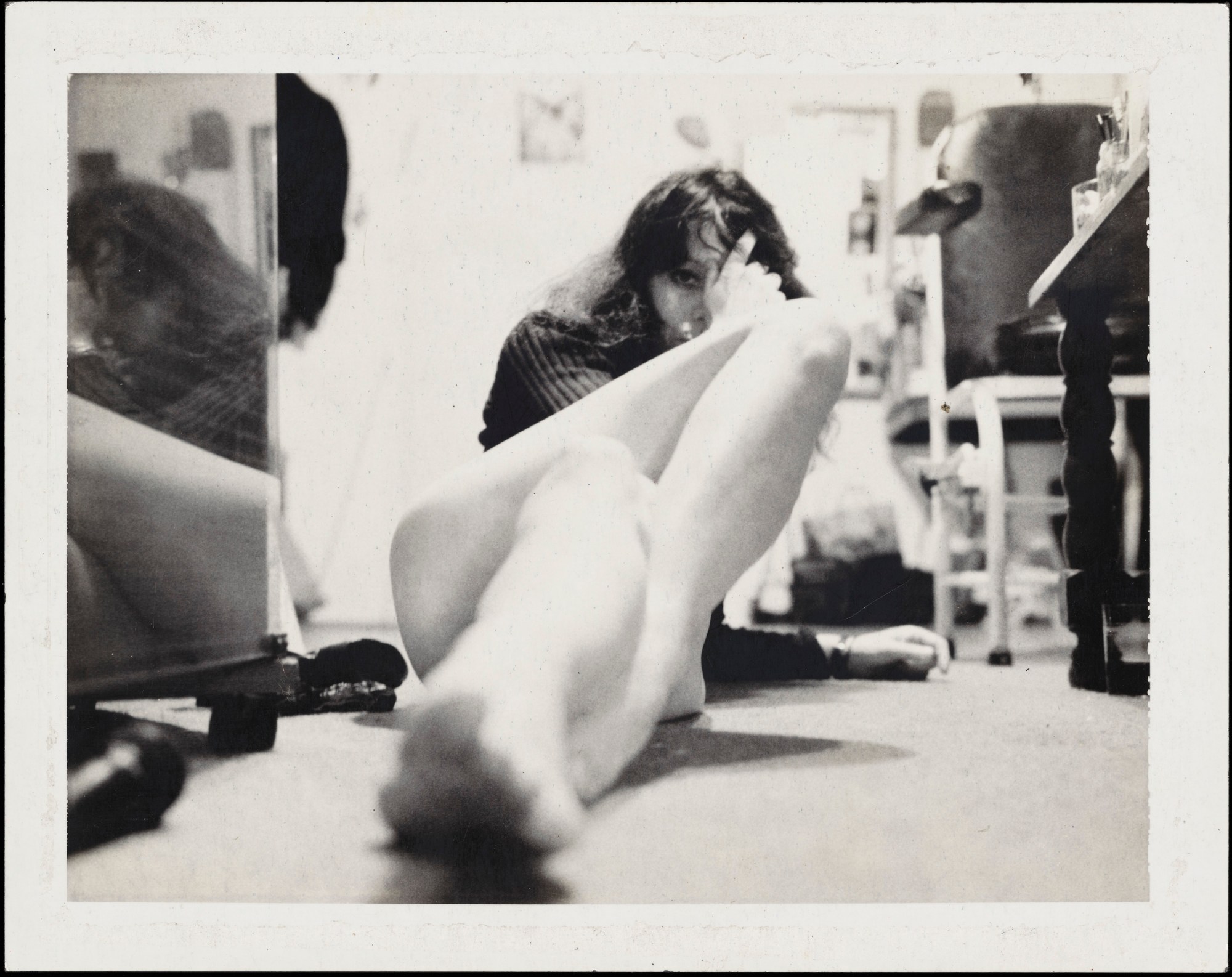

That’s just the thing. Mark’s work, my work, it’s from the life we live. Literally, from our life. If it’s something we are living, we’re photographing it. Mark photographed his lovers, he photographed himself. Same with me. And same with Nan. Jack, too. What you’re living is what you’re photographing. It’s intimate.

In your show, there’s a picture of Nan at Mark’s memorial. She’s written beautifully about photography and memory. How do you see the relationship between them?

What I see in Nan’s writing, but mostly in her work, is the essential talent to see the light — the force that glows from life. When she wrote that she photographs her friends to keep them alive, I melted. How beautiful. One doesn’t have to go out and look for anything. It is all right there.

She came to New York before you and Mark.

Yes. Nan cast a large shadow at the Museum School. Everybody knew her name, Mark was friends with her. But he was with her only for a semester. She had left by the time I transferred. Just her shadow was there.

They did a great catalogue for a show we were in at Santiago de Compostela, in Spain. It was called Familiar Feelings, The Boston Group. The curator broke us up into groups, really clearly, of who was in Boston first, where they studied. Jack and Tabboo! at Mass Art, Mark and I at the Museum School. Nan and David Armstrong in a period of time together. PL [Philip-Lorca diCorcia] and Shellburne [Thurber] at the Museum School before Nan.

Does it feel strange that you’ve all been put in a sort of collective?

A little. The term “The Boston School” was only the name of an exhibition at the ICA. Nan titled the show with Pat and Lia Gangitano. Then it caught on and turned into something else. But I think, in a way, we were feeling the same things. We were all photographing things that were close to us. On the ground, I call it. Working with things that were real.

Tell me about your relationship with Polaroid film, and how you manipulate it.

I’ve always been very open to chance, to accidents, to breaking the rules. Risk-taking with the Polaroids. The process at the start was accidental. My life was really torn at the time, so it was very symbolic, to me, of life — the way things propel, and do what you least expect. You try to control it, but it’s still gonna do a little bit of its own thing. I found that the Polaroids were doing something similar. I really related to that.

I would wrap them in plastic, all stuck together. I wouldn’t rinse them off. I’d put them in a closet, under the mattress, something ridiculous. Then I’d forget about them. Go back to them a month, sometimes a year, later. And there it was. I learned if it was warm outside, they’d react this way. If it was cold, they’d react this way. I started to learn how it would react, but not exactly. That was what was so beautiful about it. You never know what’s going to happen. I photographed whatever was happening around me, and my friends are very creative people. I call it play. You bring your toys, I bring mine, and we’ll see what happens.

I think of the Polaroids as living things. They’re symbolic of the passing of time, and our decay. There’s an impermanence to them that shows how short and fragile this journey is. I allow the very thing that destroys us — what we and what all living things naturally fight against, “death” — to reveal beauty.

Did the process of reviewing work bring to mind any fresh ideas about older pieces?

Yes. The Polaroid itself sometimes says something very different than the negative does. When I’d see interesting pieces, I’d look for the negatives. I started bringing color into the mix, which I hadn’t done before. I bought some colored inks, and painted on the photographs. My work is really dark, you know. It’s sad. It’s about death and life. I wanted to bring color into the picture. “It’s not so bad! Here’s some yellow.” [ Laughs].

“Between the Sun & The Moon” is on view at Daniel Cooney Fine Art through December 22, 2017. More information here.

Joey in Brooklyn, 2009, Gail Thacker