Recession, generational conflict, sectarian wars, rising and falling borders, failed states, global panic, terrorism, democratic protests cracked down upon with violence by totalitarian states, crisis in the European Union, the lurking fear of a great Other ready to bring annihilation to our way of life. That could be Europe today, or the 80s, or, 90s. Europe is in crisis, again, like it’s been in crisis before, and no doubt, it will be in crisis again.

This crisis, a slow burning, deeply spiralling mess, feels intractable right now. The last few weeks have brought it to a head with Brexit, but it’s not just Brexit, our small-minded desire to separate ourselves from the problems just across the Channel (and to blame all our problems on them) but that Brexit is simply a signal of — and indivisible from — the wider problems that define our times; revanchism, chauvinism, fascism, racism, the refugee crisis, the financial crisis.

Europe’s navigated these crises before, will, hopefully, navigate them now. That, at least, is the proposition of a new exhibition at the Van Abbemuseum, in Eindhoven. Titled The 1980s: Today’s Beginnings, it charts the long 80s, roughly from the death of Franco, Spain’s fascist dictator, in 1975, to the fallout from the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

It’s an exhibition that charts the way a generation of artists (in the broadest possible sense) from across Europe fed into the political discourse of time, became an indivisible part of it. It’s not an exhibition about the art object, an exhibition heavy in paintings or sculpture or the massively spectacular, but instead an archival attempt to bring to life various art movements who resisted traditional art methods, who worked instead in mass media, performance, temporary spaces, and most hearteningly, in straight up activist work.

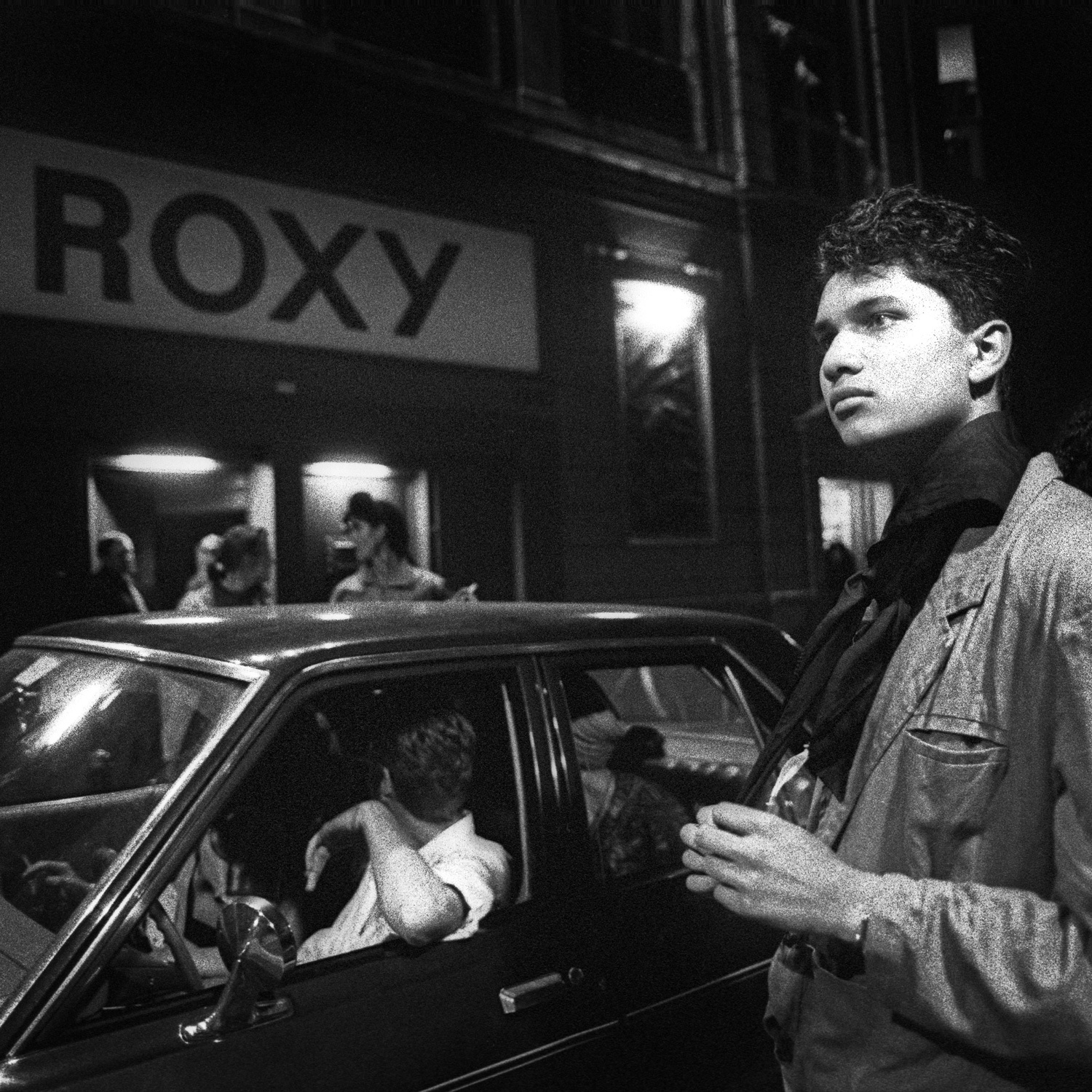

To this end the exhibition takes in a variety of places and times. Barcelona post-Franco, when Video-Nou took video cameras onto the streets to document the country’s messy transition towards democracy; it chronicles the art and activists that came out of the Dutch squatting scene; the black British artists who challenged Thatcher’s racist establishment; the Turkish movements that fought against the militarism and chauvinism of society; the queer scene in Madrid, who were active in the late 80s, fighting for LGBT rights; the NSK, from Slovenia, who utilised the motifs and imagery of fascism as a challenge the Balkans’ history.

The 80s was a decade that redefined the relationship between citizen and the state. The rise of neo-liberal economic ideology in Western Europe, entrenched by the collapse of the Eastern Bloc and Soviet Union at the end of the decade, lead to the privatisation and corporatisation of politics. This is the big, master narrative of the decade of course, but the art movements tracked at the Van Abbemuseum exist in the margins of it as a secret history of an alternative 80s.

So if the 80s is the story of the reshaping of the relationship between citizen and state, the exhibition tells the story of a redefinition of the relationship between art and institution, art object and art market, artist and society. It’s the story of art from the street that responded to the social problems of the street. It’s the story of the creation of a new voice, being shouted by many people across Europe. It’s a European conversation about where Europe was, where Europe was moving at the time, and by extension, a lesson in Europe now. The exhibition is the combined work of six other institutions from across the continent, funded in part by the EU, which felt prescient, visiting the week after the EU referendum.

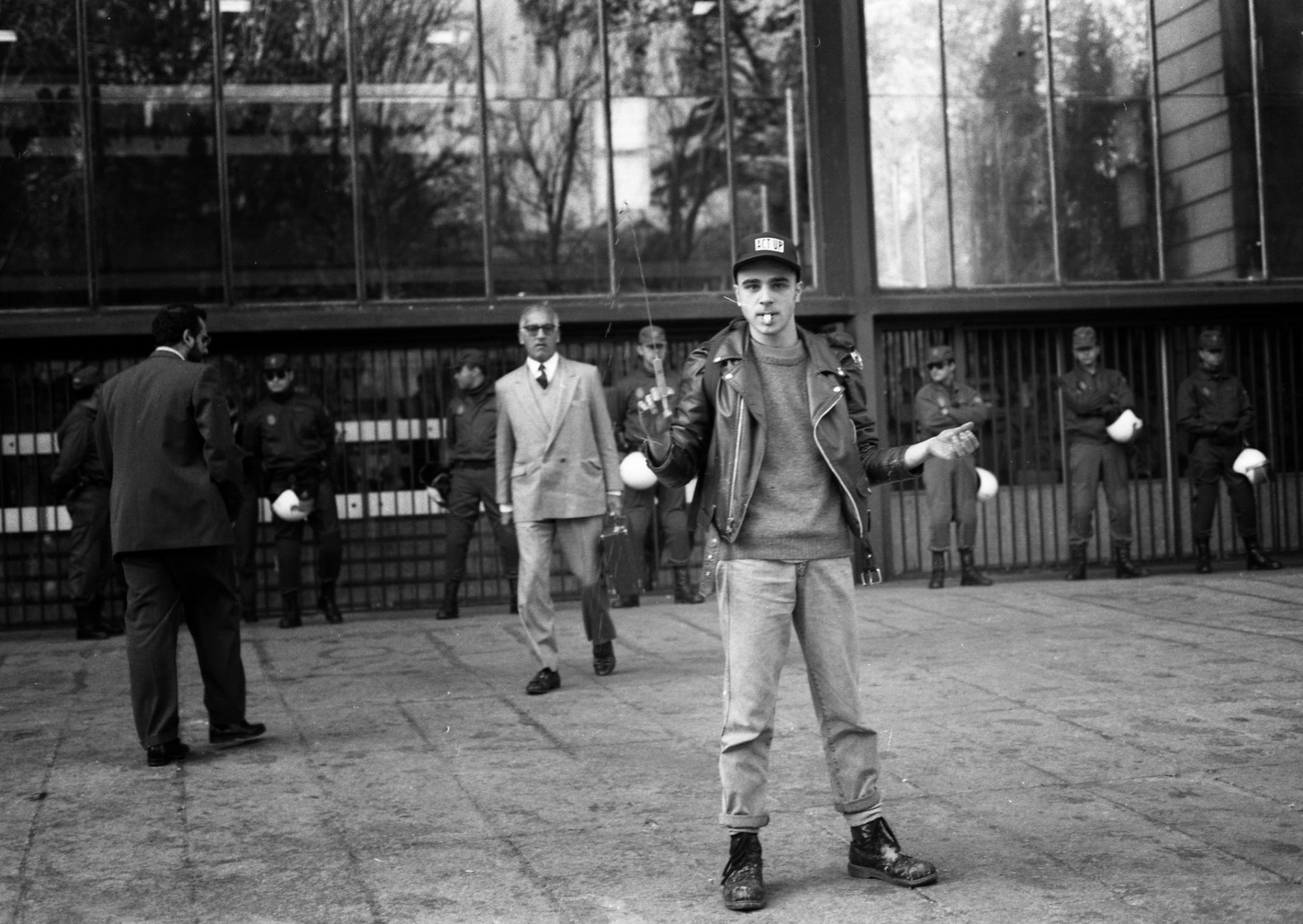

The long 80s tracked by the Van Abbemuseum began when Francisco Franco died in Spain, in 1975, having ruled the country since 1936, the only one of Europe’s myriad fascist dictator to die peacefully in his bed. Following his death the monarchy was restored and Spain began transitioning towards democracy. Video-Nou was founded in 1977, over the next few years they worked on 30 interventions, documenting the transition on camera, enlisting citizens to help. Forming a network of independent groups, they utilised the new forms of mass media to tell previously untold stories, empowering those denied representation under Franco. Whilst they were primarily engaged in documentary making, they also crossed over into workshops, they used their documentaries to spread information, enlarge the discourse of the time. Fascism had crippled political life in the country for over 30 years, this was an attempt to revive it. It was a citizen-led documentation of citizen-life, which commented on the issues of the day, as well as the cultural renaissance of the era, the underground activities in art, theatre, film and music that accompanied it. It’s a model that would spread across Europe in the coming decade, that is to say, documentary as artistic practice.

Notably in Turkey, their part of the exhibition curated by Salt Gallery in Istanbul, plots the reaction of people in the wake of the country’s military coup in 1980, and the country’s transition to a market economy and its uneasy relationship with Europe and its Europeanness.

One of the exhibits shows the Turkish Eurovision entry for 1980, Ajda Pekkan’s song Petrol. It shows the place Turkey was in at the start decade impeccably. The song is a classic cross-cultural banger, it starts with traditional Turkish drums and vocals, before exploding into an emotive disco-esque chorus. It’s an exemplar of Turkey clashing between its traditions and new forms that represent an image of European liberalism.

The main focus of the Turkish section though is a cultural archive of resistance; it compiles footage of Istanbul’s redevelopment, marches for human rights, and interviews with politicians. It chronicles the informal art practices that sprang up and who organised actions against compulsory military service and misogyny, for the environment, sexual health, and gay liberation. One of the focal points of this scene was Sokak (Street in English), a kind of Turkish i-D, which sprang up at the end of the decade and documented the cultural underground and championed its social resistance. Sokak was the voice of the youth in the country at the time, once of the first places Turkish kids could find an outlet for the lives they were actually living, a reflection of the society they were living in, and a programme for making things better.

This idea, that wider culture needed to reflect what was actually happening, that culture must find a new means of representing a new reality, runs throughout the exhibition. It deals with how art can not simply reflect reality, but also how art can make things better.

“I saw people fight with police who I thought would never harm a fly,” a woman says, in a documentary that chronicles the Dutch squatting scene of the era. The squats started as a reaction to homelessness in the country as property developers kept buildings empty to drive prices up. As a reaction to this the squatters turned empty spaces across the Netherlands into co-op housing, art spaces, and studios. De Fabriek, based in a former book bindery in Eindhoven, was turned into an exhibition space. V2 and Het Apollohuis in Rotterdam became not just local centres of counter-culture, but international ones, linking up the nascent Dutch movement in art, music and politics into wider international ones. The biggest though, was the Vondel Free State in Amsterdam, a squat which posed such a challenge to the city, that the government rolled tanks through the streets it to crush it, the squatters resisted erecting barricades, forcing the army and police back for a time.

Maybe it’s indicative of how precarious society was then, how poised it was between the old and the new, that such a challenge to its authority had to be so ruthlessly crushed. Squatting is about space, a space to exist in; a marginalised group taking back the space of society that they feel they are denied by those power. That might act as a neat microcosm for all of the movements profiled here; not necessarily, simply, physical space, but intellectual space, the space to exist in a society if you’re gay, trans, black, poor, all of the above. It’s this too, which is most relevant today, what we can take away from the exhibition, how we can plot a future through our own European crisis find our own spaces to exist it.

One of the most heart wrenching (but inspiring) sections documents the black British art movement, led by figures like John Akomfrah, Keith Piper, Chila Kumari Burman, Lubaina Himid. They took post-colonial theory back to its point of origin, confronting how that colonial legacy manifested itself in a racist present, in police brutality, racism, exclusion, problems that are hardly historic.

The landmark work of the era was John Akomfrah’s Handsworth Songs, commissioned by Channel 4. It’s a document of the race riots that broke out in Britain in 1985, in Handsworth, Birmingham, and Brixton, London. Handsworth Songs is a cinematic collage, it takes in newsreel footage and interviews, it’s a journey through the images and reflections of Britain at that time, a society that felt unlivable for many ghettoised black people. It was shown by Chanel 4, important, it broadcast the reality of this life into people’s homes who might otherwise have not cared, not seen it, or simply got their information from racist tabloid newspapers.

The issues these artists raise feel more prescient and powerful than ever, you can imagine, 30 years from now, similar exhibitions dedicating similar spaces to the Black Lives Matter movement, the Occupy movement, the anti-austerity movement, the Nuit De Bout in France, the 15-M Movement in Spain. We’re still here, still demanding radical change to the way our society operates.

Credits

Text Felix Petty