It’s been ten years since Aitor Throup graduated from the RCA and embarked on a path that saw his practice stray far from the typical idea of what a menswear designer ‘should’ be. His work is resolutely multi-disciplinary; he finds new forms of inherently personal expression in not just clothing but photography, sculpture, costume design, and creative direction.

His new online archive offers a comprehensive look at the first decade of his career, in which time Throup established himself as one of the most distinctive creative minds of his generation.

Throup’s formative years were spent astride the soccer terraces of north west England, and like the designers who fashioned the futurist garments of that tribe, he, too, is forward-looking. He’s always immersed in the next project, the next concept, the next ‘reason’ for doing what he does.

The decision to launch this archive, however, offers the chance to momentarily look back. It was inspired by two emails received in the space of a week, both of which encouraged a period of self-reflection: one came from the RCA, making him an honorary fellow. The other came from the family of his hero, Massimo Osti, asking him to write the introduction for the latest monograph on the late founder of Throup’s beloved Stone Island and C.P. Company.

Here, we take the opportunity to discuss with Throup the various strands of his work to date, and the intensely instinctive way of working that makes him so hard to pin down.

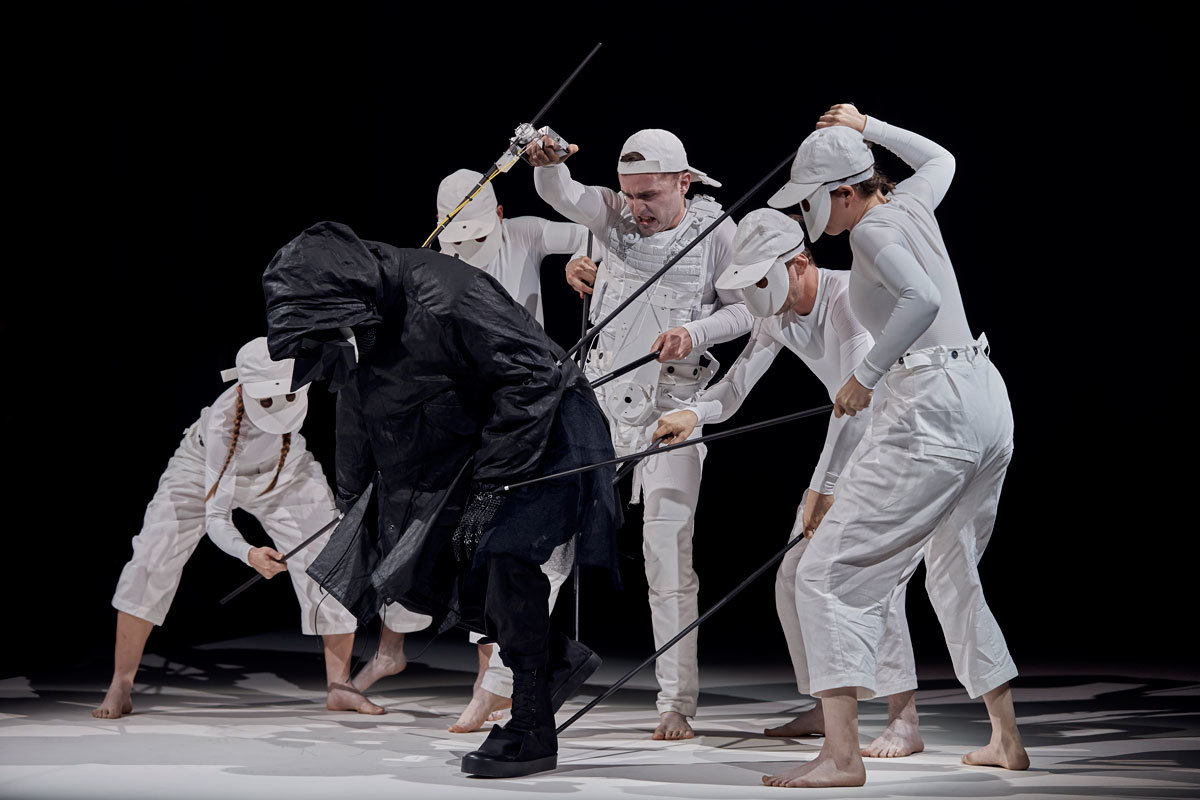

The Rite of Spring photographic series, 2015

What effect did those emails from the RCA and Massimo Osti’s family have on the way you viewed your work to date?

I guess it got me out of my head, made me zoom out a bit. I was aware of an almost enforced perspective on myself, which is really useful. I think in general we can get quite lost in our lives due to a loss of perspective. It made me look at what I’d achieved up to that point in a constructive way, analyze my work as a whole and arrange it into a set of building blocks that I could utilize in a positive way going forwards. I realized that all of these tiny ‘boxes’ of work, these little concepts of constraint that I’d created over the years — when you put them all together it actually created one bigger box around me! One that was much freer to work and exist within.

Could you elaborate a little on why you think these ‘boxes’ — the way your ideas manifest themselves in various forms — are so important to the way you think about your practice?

I believe that any timeless creativity, any timeless art or design, is the coming together of expressive emotions contained within a contextual or conceptual framework. That’s what I’ve lived and worked by all my life, really, even as a kid.

Why is it do you think that those frameworks lead to such a multi-discipline output?

It’s very much about the nature of my work. It’s not the ‘aesthetics’ — they’re incidental. The way I see it, the nature of my work is reason. It’s like Kubrick said, ‘if there’s a great story to tell then he can make a great film out of it…’ The nucleus of any physical expression is non-physical. Put it this way: as a filmmaker you’ve got two choices: you’re either searching for the perfect story or you’re searching for the perfect filmmaking tools. Kubrick was searching for the perfect story and I realized I was equally interested in not only the perfect story, but also the reason behind that story. I look for the perfect reason to express something and actually, I’m never thinking about what ‘it’ is that I want to create. I have a need to understand why I’m trying to say anything.

How does that manifest itself in the way you work with others? For someone with such a singular approach, collaborations have formed a big part of your work to date — with brands such as C.P. Company, G Star, Umbro. Also with musicians such as Kasabian, who you have a particularly strong link both personally and as a Creative Director. Is there ever conflict between your own ideas and theirs?

Whenever I work with anybody in that capacity it’s because they accept my methodology. My approach is all about respecting the reason, the nucleus. They let me into their environment just to research, soak up, understand the reason before I come up with anything tangible for them. Inevitably I might have some preconceived ideas about a musician or a brand and how [my ideas will come out] but I have the same preconceived ideas when I’m designing, say, a suit jacket. When I begin working on any project, I’ll go in and leave those preconceived ideas outside — I guess I’m constantly trying to unlearn what came before.

The brands you work with that we’ve already mentioned — even to an extent musicians like Kasabian — it only takes a cursory knowledge of British subcultures to know they’re all very much linked with soccer, terrace culture… whatever you want to call it. How did that come to be a part of your world?

I was born in Buenos Aires where we stayed for seven years and came to Madrid where we lived for five years [before moving to Burnley, North England at the age of 12]. I was always a big soccer fan but as a kid I could never go watch the soccer — it was too dangerous in Argentina and in Madrid it just wasn’t accessible to us, we were poor. All of a sudden we ended up in Burnley, Lancashire and as tough as it was, the one positive I could take from it was how accessible the soccer culture was. I used to go and watch Burnley every Saturday and just grew up around the culture, the casuals, their uniforms — all those brands we’ve talked about.

And how does your work — often these high concept projects — fit within that culture, as you see it?

Well this quite unique thing happened within that subculture where these working class, often quite violent men found a channel of creative expression through clothing that was actually already incredibly avant-garde. I find it fascinating — Paul Harvey, Moreno Ferrari, Osti himself, and even Carlo Rivetti [of Stone Island] — they are futurists. Nobody really talks about this but it is an incredibly unlikely relationship between these amazing garments and these very generally non-expressive British men who adopted their work. You see it through history even, with the dandies, the mods… Even as a teenager, I just went deeper and deeper into the avant-garde side of these clothes, I thought it was fascinating. I quietly became obsessed with clothes, as long as they had a story behind them.

Do you think those ‘stories’ are in danger of being lost a little in the future — kids whose tribalism is defined by hype blogs, purely what’s ‘cool’?

No, I think it’s just a natural split — there are certain things that exist on the surface, there always have been, and there are certain things that aren’t. If you go to a three Michelin star restaurant it’s a different experience to a Big Mac, but you’re still eating. As big as McDonalds might get, Michelin star restaurants aren’t gonna die out — and I would personally still eat at both of them!

And what about your own future? Do you have an idea of the body of work you’d like to be looking back on another ten years from now?

Not at all. I’ll just feel blessed to still be interested. I feel so lucky to have found my path. Once you find that, it’s like Dorothy on the yellow brick road. That sense of direction is so much more precious than the actual destination. My aspirations are just to stay on that path. Keep doing what I’m doing for the right reason.

Credits

Text James Darton

Lead image art direction and styling by Aitor Throup, from i-D, 2009

Photography Neil Bedford

Styling assistance Stephen Mann

Aitor wears trousers, shirt, snow parka and moulded gloves from the A.T. Studio archive. Inside-out vintage goggle jacket from the C.P. Company archive.