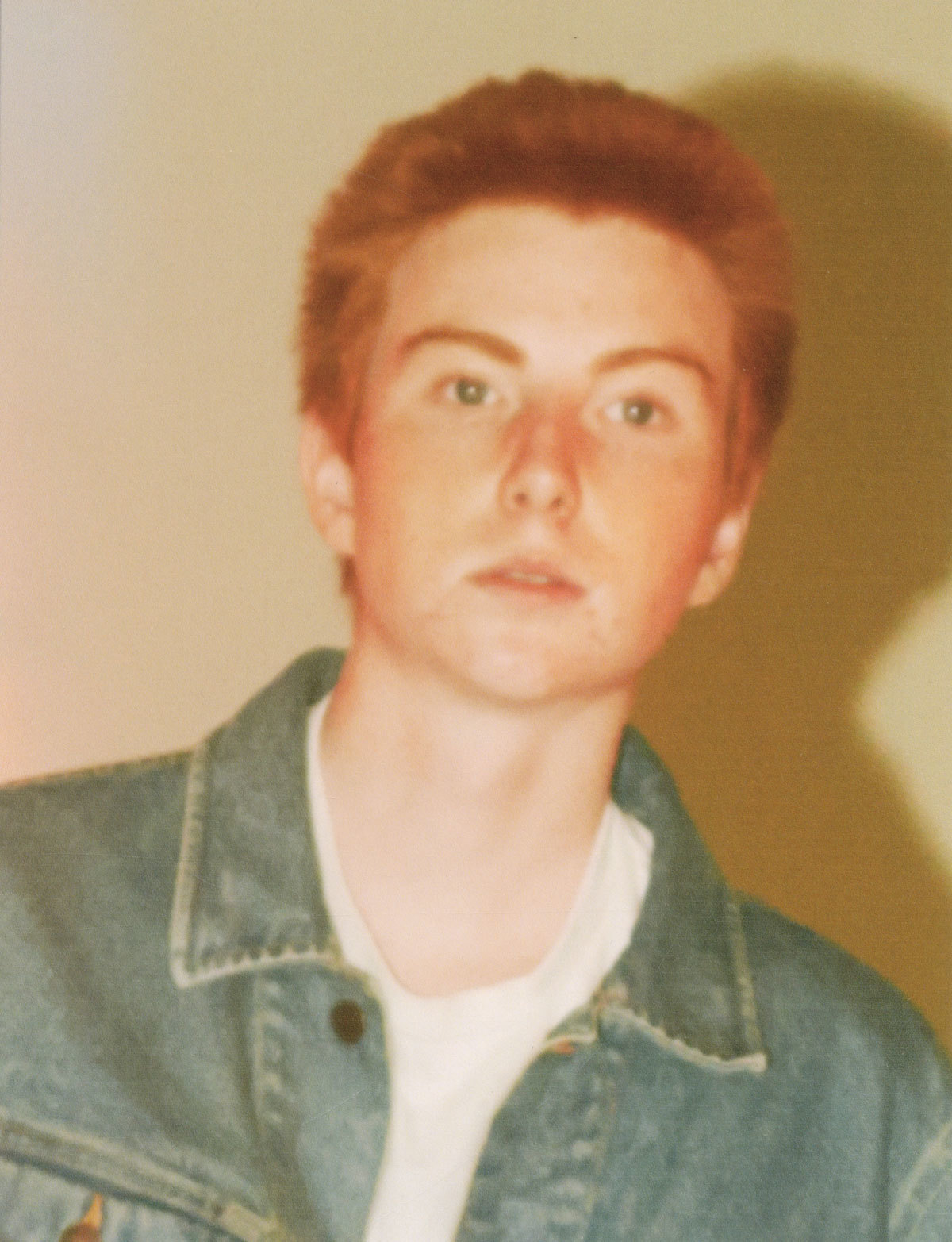

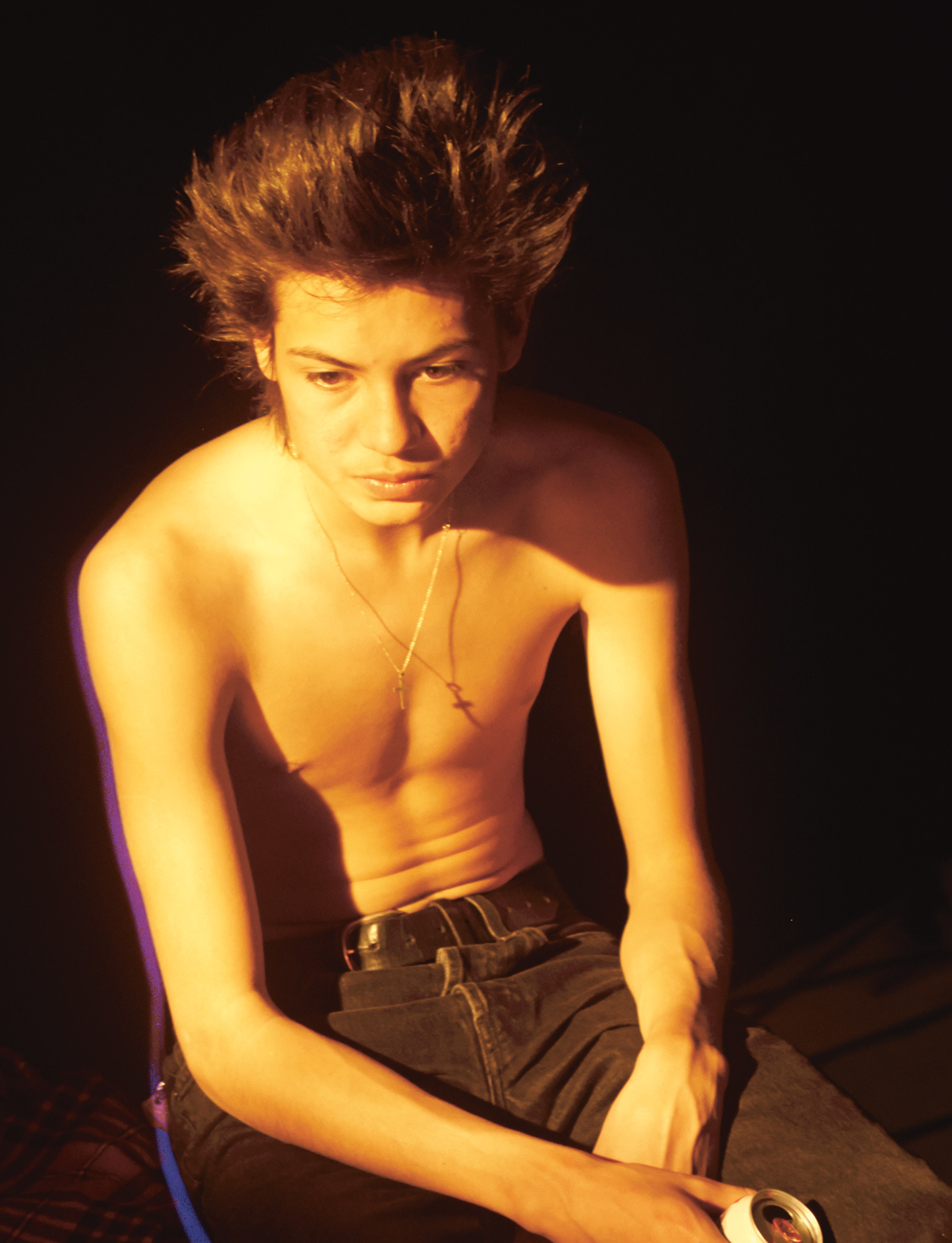

“Wake up. Coffee or tea, depending on how I’m feeling. Call a friend. Skate. Hopefully get a trick, or just fuck around. Kick it. Eat well.” Sage Elsesser is describing a day in his life as one of the “Fucking Awesome kids” (the FA kids, that’s what they’re called) skating for Supreme. He’s 18, from Los Angeles and now living in New York and his day sounds like lyrics on an Underworld track. I ask the same thing of 17-year-old Sean Pablo, who’s from Los Angeles and still there. “From the moment I wake up to the moment I fall asleep…” he says. “No, just kidding! I just kick it until everyone’s ready to meet up, and then usually drive around to different skate spots.” And afterwards? “Maybe get some beers and sit at a park or something.” Skating, so the saying goes, is a way of life.

It’s not a sport, even though the most talented can make millions in competitions these days, and a shoe company once flew me all the way to Barcelona to watch Nyjah Huston land a switch hardflip and then write about it in this magazine, and there was a party there on top of a hotel with Monster-energy-drink cheerleaders. It’s not a form of transportation, although it is a form of transportation, really. It’s not a marketing tool, even though Selfridges built a colossal skatepark underneath its London store last year. It’s not sexy; despite what magazine shoots like this might make you think, in most places in the world growing up a skater will not attract lots of girls – maybe in London or New York where skate kids go out with fashion designers and stylists and models, but not in most places. It’s not a fashion statement, although it is fashionable, you know – when I interviewed J.W. Anderson a while ago in his old studio on Shacklewell Lane he had hung above his desk a Supreme skateboard by Harmony Korine, printed with a ghostly pale photo of Macaulay Culkin. That’s pretty fashionable. (I asked him, “Is that a skateboard printed with a picture of Macaulay Culkin?” and he said, “I don’t know” – typical Jonathan.) Somehow skating is always cool. It’s just one of those things that has somehow stayed cool for decades, that’s never not cool – like David Bowie, or Japanese culture – and now it’s bigger than ever.

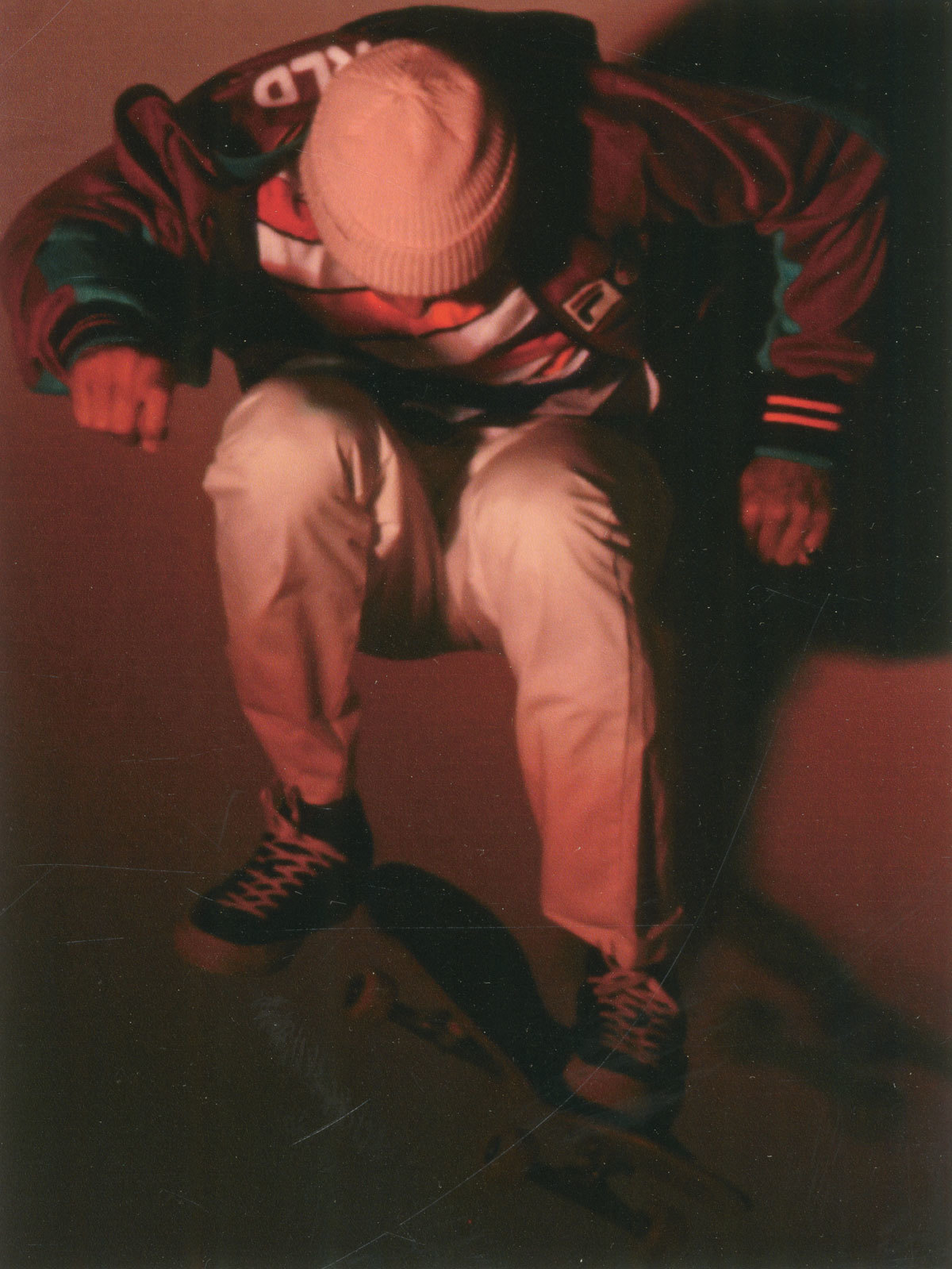

But anyway skating is none of these things; skating is a way of life. You’ll see this very clearly if you watch Supreme’s videos such as Cherry – their feature that finally came out last year – or the many shorts that appear unannounced on filmmaker William Strobeck’s YouTube, falling from thin air like sweet little comets. They’re not only about landing tricks, or even necessarily trying tricks; they’re also about just hanging out. They’re artistically-produced documents of a youth culture. Because skating is so often a rite of passage. It was for me and many of my friends, who turned out as conceptual artists, or master-chefs, or managing editors who live in the suburbs with their wives and kids (who also skate). It can change your everything whether you’re growing up in Southern California and grinding down ten-stair sets before even turning ten, or coming of age in the Oxfordshire countryside and hardly able to ollie up a curb (*cough cough*). Even James Jebbia, the founder of Supreme, actually spent his teens in Crawley, West Sussex. If you were a disaffected teenage boy, disgusted or just bored by popular culture and searching for an alternative – and who wasn’t really?! – in the 80s or the 90s or the 00s or now, and you lived in a country with pavements, then it’s likely that you would’ve been a skater at some point.

Nowadays it really is a way of uncovering your identity as a young man, of defining who you are. And of course it has its own powerful culture – not only the physical activity of skating, but the whole universe it creates around itself. When I was a teenager it wasn’t only about trespassing in business parks on the outskirts of Didcot and failing to land any tricks, it was also about watching an alluring other world illuminated on a glowing screen at night. There’s something deeply hypnotic about sitting on a sofa as a teenager, smoking overindulgent, silly amounts of skunk and staring at a lot of other teenagers landing trick after trick after trick for an hour or so (and then watching that same video over and over and over again). It’s very boring at times – almost unbelievably so – but also oddly compelling, and sometimes illuminated by sudden moments of absolute wonder. Boys like to geek out on stuff, and skating offers so much to geek out over. The best skaters have tricks that appear impossible, that appear to slip outside of the physical reality of the cosmos and move in other dimensions, and they can land these things so stylishly, nonchalantly, as though there was nothing to it — weird things, like inward heelflip variations that are too confusing to meaningfully describe in words but nonetheless very popular. My mates and I used to slump on the sofa spinning the television-remotes through the air in an effort to comprehend the most complex motions a rectangular object might perform in space and time. Mind you, we were pretty stoned. This was a long time ago.

Skating is artistic. Supreme have collaborated on boards with the likes of Jeff Koons, Larry Clark and Richard Prince. Sage Elsesser is going to art school. And it’s not at all surprising, because the very act of skating is itself an art form – sort of like dancing-on-ice for lads, or a less painful form of ballet. Because it’s not so much concerned with what you can do as with how stylishly you can do it, and how imaginatively you can find architectural arrangements upon which to do it. Gracefulness and invention are much more important in this, than in other teenage male pursuits.

Back to that stoned teenage sofa. Not only was watching skate videos a higher-level education in obscure East Coast rap, but all sorts of other things turned up on the soundtracks too – the first time I ever really understood, really listened to David Bowie was when two of his songs (1984 and Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide) played out across Arto Saari’s magisterial double-part finale to Flip’s Sorry. Each video is like a mixtape that’s had years of thought put into it (because that’s how long most take to make) and I learnt so much about music because of them. (In case you’re wondering, Sage likes Wendell Harrison, Nina Simone and Bill Evans as of late, and Sean Pablo digs New Order, Earl Sweatshirt and Brian Eno.)

When you’re young and bored with your surroundings these videos open up a window to the world out there, with all its exotic cities and lush, concrete, brutalist architectures – usually experienced at very high speeds, as if trapped in a futurist painting, under brilliant blue skies and sunshine from somewhere far away from you. The life of a professional skater appears as a dream. Today, often when visiting strange cities for the first time, I find myself recognizing some utterly unremarkable municipal plaza or somewhere as if I’d visited it in a past life, and it’s an unsettling, magical feeling. Recently I was walking through Koreatown, Los Angeles, and stumbled across an unattractive, unprepossessing 15-stair-set with three harsh handrails and an impassable line of yellow bollards at the bottom, and immediately it took a hold of my psyche. These were the Wilshire Rails, once a world-famous spot until those vicious bollards were installed as a deterrent, and after which they had their own four-minute video eulogy on Baker’s Bake and Destroy video. I found it all quite emotional. Skating changes the way you view the world, often to an alarming extent, it completely consumes you. Even today I find myself walking around the city staring at handrails and staircases – rather than, say, sexy passers-by – and hallucinating improbable tricks across them. You’ll never look at architecture in the same way again.

Skating contributes to your idea of what it is to be a man, for better and worse. The first time I blacked out on alcohol was with my skater mates. The first time (well the only time) I saw a friend stick a bottle up his own ass, for no apparent reason, was at the skatepark. (Hi, Aaron!) The first time I saw one mate smash open another mate’s head was with a skateboard, and it was horrible. In skating – as in most things young men do – there’s lot of drinks and drugs and sometimes lots of money, and usually few authority figures or girls around as calming influences. Often things go wrong. But mostly it’s a world of positivity and kindness and acceptance. Not to mention that it takes a hell of a lot of hard work to learn any tricks whatsoever. “One of the great activities is skateboarding” – this is what Jerry Seinfeld says to Chris Rock in their shared episode of Comedians In Cars Getting Coffee. “To learn to do a skateboard trick, how many times you’ve got to get something wrong until you get it right. And you hurt yourself and you learn that trick – now you’ve got a life lesson. Whenever I see those skateboard kids, I think, ‘Those skateboard kids will be all right.'”

On the internet there’s an extraordinary video of Ishod Wair (Thrasher magazine’s skater of the year 2014) which documents all his attempts in one day at landing just one very hard trick in Love Park, Philadelphia. I could watch it over and over again. Basically he throws himself down some huge steps into a fountain 72 times in a row, and breaks a board and dislocates a finger in the process. But anyway he lands the trick and everybody’s very happy, everybody’s jumping around and cheering and hugging him – even complete strangers – and it’s rare that you’ll see such a moment of communal joy in any city space anywhere, let alone a fairly cracked-out square like this. But Ishod lands his trick and fills the Love Park fountain with happiness, and there’s an outpouring of bliss and smiles all round. (If you wish to watch this it’s called ‘Ishod sw bigspin Love Park Gap UNCUT’ on YouTube.

Self-belief, a relentless approach to public architecture, physics, unexpected musical choices, a sense of community – there’s a lot going on in skate culture. “My pops always encouraged it,” says Sage. “I ended up playing sports for a bit, but found myself always wanting to skate. So I stuck widdit.” Asked what makes the FA kids so special, he says: “We truly are all close friends, I can call all of them my brothers. We have grown together.” In some ways, skating fosters a far stronger sense of brotherhood than traditional team sports because it’s not about winning (there’s no such thing) but about hanging out with people you like, in the nights as well as the days. It’s a way to make friends, and form a gang, and together you can completely reinvent parts of the city, and claim it back – at least temporarily – and create your own social space out of its architecture.

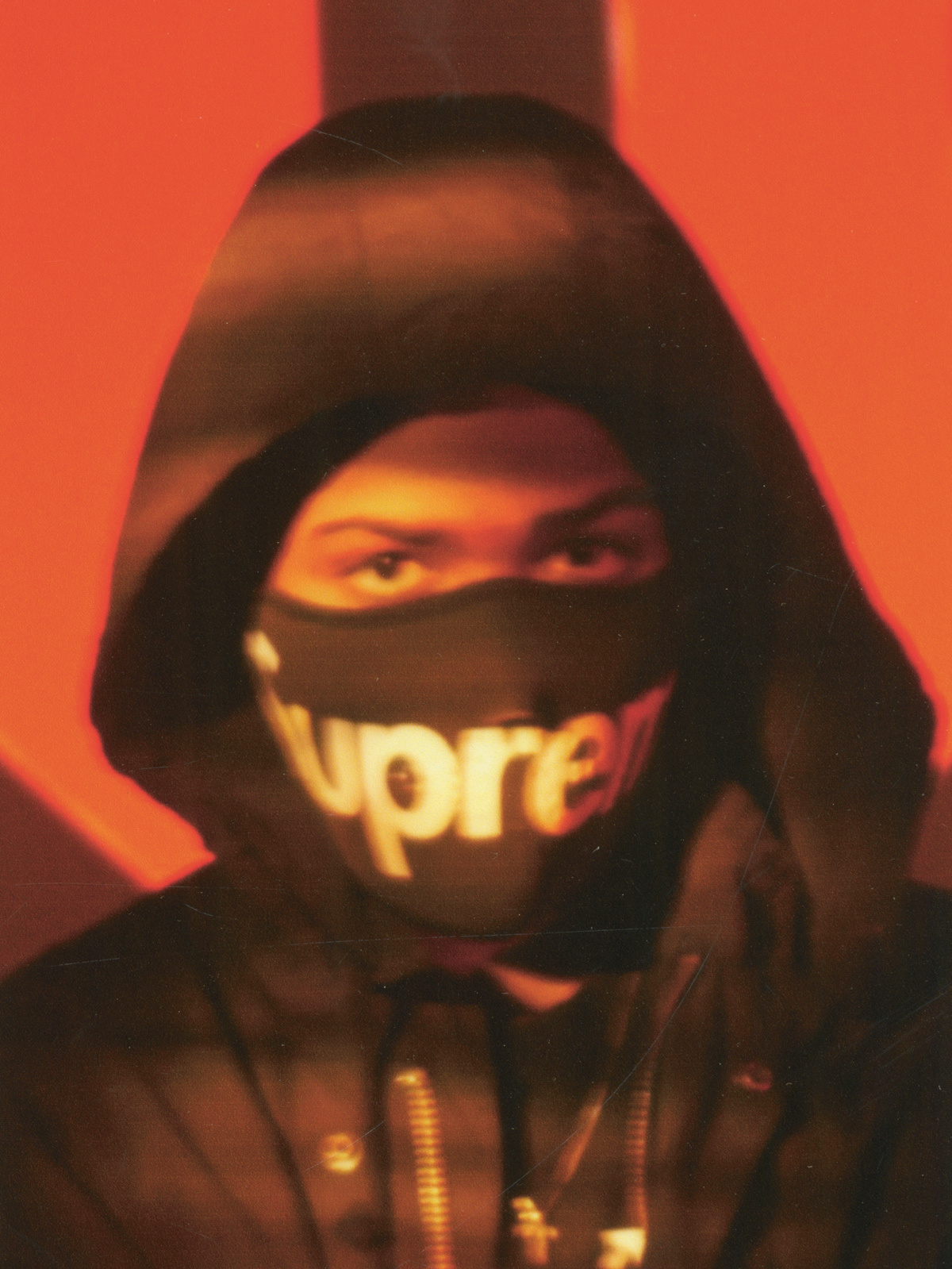

When I ask Sean Pablo to describe the identity of Supreme he says: “Ha. I don’t know. Fuck what other people think, we do what we want to do.” And the most important thing about skating – I think – is that it teaches you to believe in yourself. To tell yourself, “I can do this.” It also offers a vision of manhood that’s less obsessed with sexual objectification and financial success, and more interested in self-expression. And really it’s about an individual traveling through the world at high velocity, and transforming every obstacle into a possible playground, and having a laugh.

Credits

Text Dean Kissick

Photography David Sims

Models Sage Elsesser, Tyshawn Jones, Aidan Mackey, Sean Pablo Murphy

All clothing Supreme