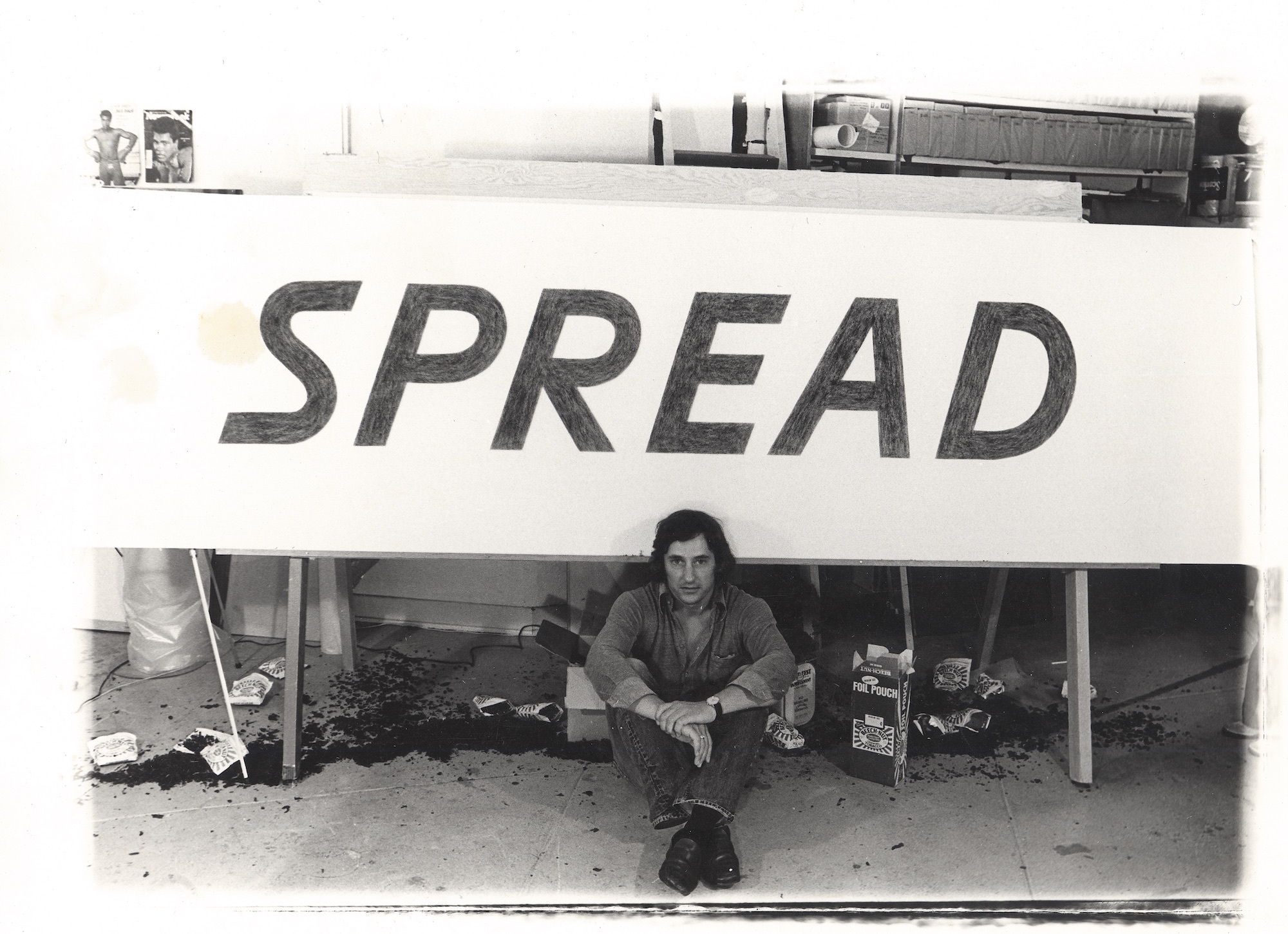

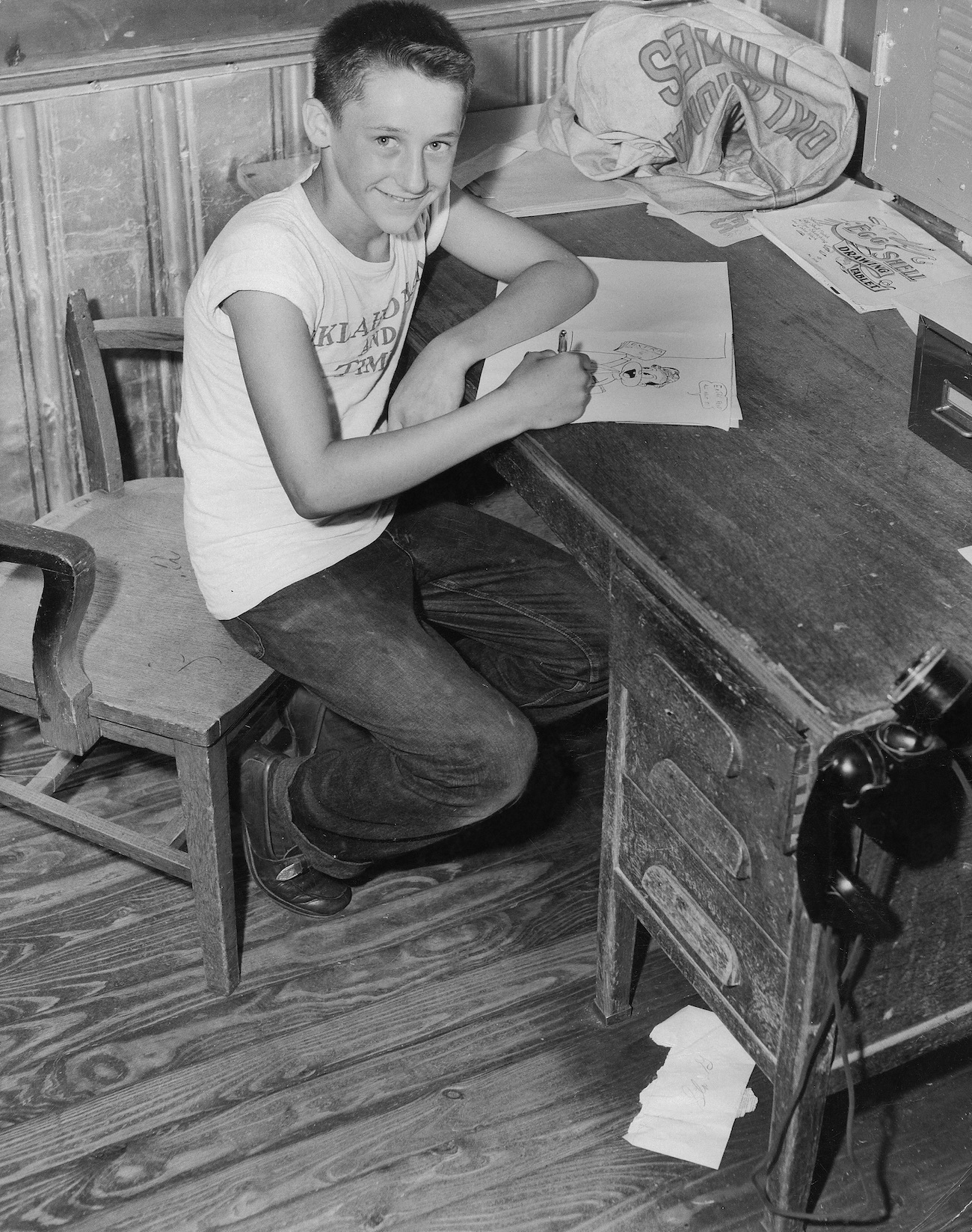

Ed Ruscha, one of America’s most iconic living artists, has been making work for over 50 years. Though word paintings and gas station photographs are among his most recognizable pieces, Ruscha’s practice includes drawing, printmaking, self-publishing, and collage, too. But despite working in Hollywoodland for half a century, Ruscha has only ever made two films: 1971’s Premium and 1975’s Miracle. They’ll both screen this Sunday, July 31, at LA’s Museum of Contemporary Art, where they’ll be accompanied by Ed Ruscha: Buildings and Words, a new short-form documentary that synthesizes Ruscha’s life, work, and obsessions.

Written and directed by Felipe Lima, the documentary (which makes its premiere on i-D) weaves together archival footage and personal photographs that span nearly all of Ruscha’s life. And if its narrator’s voice sounds familiar, that’s because it’s Owen Wilson — who became a Ruscha fan 20 years ago, in 1996, when he happened across a Ruscha painting while filming scenes for Wes Anderson’s debut feature, Bottle Rocket. He now collects Ruscha’s pieces, and the two have become good pals.

Wilson’s thoroughly informative yet conversational narration is complemented by more familiar faces, among them Kim Gordon, gallerist Larry Gagosian, and fellow West Coast-based art titans Larry Bell, Billy Al Bengston, and Ed Moses. Designer Hedi Slimane is a fan of them all: he shot black and white portraits of Ruscha in 2009, both Bell and Bengston’s works served as inspiration for his Saint Laurent collections, and by the looks of Moses’ flannel, his casual California style ended up somewhere on a moodboard, too. Each interviewee not only lends new insight into Ruscha’s practice — which becomes pretty experimental by the time he starts painting with hot sauce, jelly, and tobacco in the early 70s — but his off-beat poetry as well. To Gordon, Ruscha is “kind of punk.” Ahead of the screening, we caught up with Lima to learn more.

What first motivated you to dive into Ruscha’s work?

I love Los Angeles and Ed Ruscha’s an artist who’s always been held up as a symbol of this city, a label he long resisted. The range in his output was particularly interesting to me — at first blush, his books don’t necessarily feel related to his paintings for example, nor his films to his printmaking practice — but most of the explorations of his work that I’d seen would break it up, dealing with his efforts in different mediums separately. I wanted to find a way to draw threads between some of those works instead.

There are so many artworks and archival materials in this film. What was the process of exploring that archive like — researching and developing the narrative?

Making documentaries is a messy process. One often doesn’t know the story worth telling at the outset, so it’s a lot of following your interests and learning everything you can, like grocery shopping without a meal to cook in mind. it’s easy to get lost in this: spending days tracking down an essay you’ve only seen an excerpt from, or finding a great archival film you aren’t able to clear the usage of. On this project, I was lucky enough to work with Rachel Nederveld and Matthew Miller, two incredible filmmakers who helped me through every stage and were a constant reality check.

What was the most surprising thing you learned about Ruscha making this film?

That we lived on the same little hillside street in Echo Park! I missed him by 40 years or so, but don’t think the neighborhood changed too much in that time…

I didn’t know Owen Wilson was such a fan and collector! How did you two come to work together on this project? What did he bring to the table?

The Wilsons are from Dallas, Ed grew up in Oklahoma City: They’re both good ol’ Midwestern boys in Los Angeles, I guess. I asked Owen to narrate and he agreed immediately. I can’t overstate his contribution: not only did he breathe a life and personality into the narration that felt immediately authentic and appropriate to Ed, but he helped me tweak the writing and make it flow — lest we forget he’s an Oscar-nominated screenwriter too!

Let’s talk about some of the other people in the film as well: Kim Gordon, Irving Blum, and all these amazing artists: Larry Bell, Ed Moses, and the absolute homie Billy Al Bengston. How did you chose who to select?

Ha — Bengston is the homie! He deserves a film like this of his own. I wanted to include voices of people personally involved in Ed’s story. Joe Goode grew up with Ed in Oklahoma for example and came out to Chouinard with him 1956. Maybe the most subtle link that may be lost on some viewers is the inclusion of Mason Williams’ Classical Gas at the beginning of the film. Mason and Ed grew up together in Oklahoma and remained life-long friends and collaborators.

What do you hope people take from this film?

I hope that people realize Ed Ruscha has made an incredible body of work over the last 60 years that cannot be contained in a seven minute film, and are encouraged to explore further on their own — his website is an excellent resource and great place to start: 2,273 artworks by my count! It’s nitpicky, but I think to refer to Ruscha, or several others here, as “California artists” or “Los Angeles artists” is reductive and reinforces an East Coast art world perspective that’s spoken about Los Angeles as a city “on the verge of…” something great for the last 50 years. I hope people are inspired by Ed’s very earnest approach to art-making and the reminder that ideas evolve and the best we can do is to follow our instincts and move with them.

‘Ed Ruscha: Buildings and Words’ screens at the MoCA’s The Films of Ed Ruscha this Sunday, July 31, at 3 pm. More information here.

Credits

Text Emily Manning

Lead image Susan Haller, Ruscha with Spread, 1972. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery