The musical legacy of Grace Jones is defined by sonic innovation, provocative lyrics, and fearless experimentation. However, it was a series of consistently stellar album artwork that helped propel Jones from musician to icon — from the elongated snarl of Slave to the Rhythm to the elegant aerobics of Island Life, Jones’ visual impact is etched into the landscape of modern pop culture. This visual impact would not have been possible without Jean-Paul Goude, a French artist, illustrator, and graphic designer that met Jones one fateful night in New York in the late 70s. The resulting collaborative relationship is one of the most influential in the history of music, and has earned Goude his own exhibition entitled So Far So Goude, which recently opened in Milan’s Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea. Naturally, a large segment is dedicated to Jones, his most famous muse — but what was it that drew the duo together, and how did their collaborative work go on to define the visual landscape of the 70s and 80s?

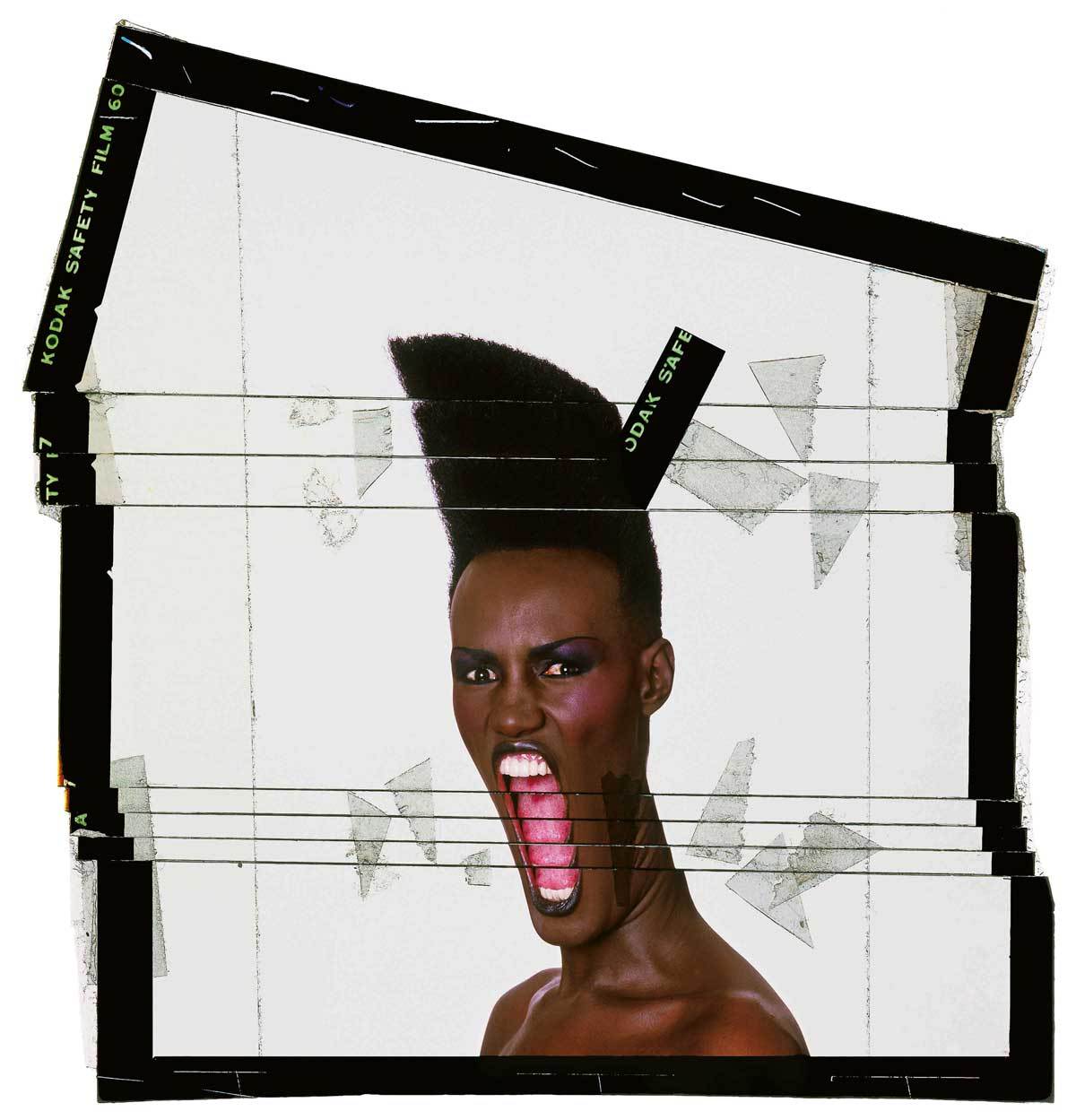

It’s well-known that much of Goude’s work centers around artistic depictions of race, ethnicity, and global culture — a fascination explored most famously in an image originally published in his book Jungle Fever, which spawned a Kim Kardashian recreation that ‘broke the Internet’ last year. His enchantment was with the far-away and the exotic, which led to his renderings of black women being branded as controversial and exploitative, although never by his subjects. He explored these themes frequently throughout his work with Jones, creating images which saw her hypersexualized, her blackness emphasized. Through the eyes of an artist, Jones became more than human — she became a strong, black powerhouse with an androgynous sex appeal and a ferocious glint in her eyes.

In her biography I’ll Never Write My Memoirs, Jones talks openly about the unrealistic expectations that Goude had of her in their daily life and how that eventually led to the collapse of their personal relationship. In a 2015 interview with SHOWStudio, Goude is similarly candid, admitting that he was initially underwhelmed by the star and dismissed her as a “partygoer with relative talents” — that was, at least, until he saw her live. Even then he admits that the music wasn’t to his taste, but he soon fell in love with the idea of her as a muse. “I became jealous and possessive of the character that, through her, I was able to create, much more than the real person.” Essentially, Goude treated Jones as an artistic vehicle first and foremost — a hyperbole which, despite destroying their personal relationship, allowed Goude to translate his grandiose vision of Jones the phenomenon into a series of imagery which painted her as a surreal, impossible muse. By playing up her Jamaican heritage and striking features, the vision of the artist and the exotic muse were united and Grace Jones became a reified translation of herself.

In fact, Jones transcended definition in almost every realm of her life. She is often referred to as a queer icon, largely due to early hits such as “I Need A Man,” which landed her an enormous gay following. She rejects all labels of sexuality, and her musical output is similarly fluid, switching from pop and disco to dub and reggae without hesitation. It was precisely this approach to music that resulted in some of her most progressive hits such as “Warm Leatherette” and “Slave to the Rhythm” being largely ignored by mainstream radio.

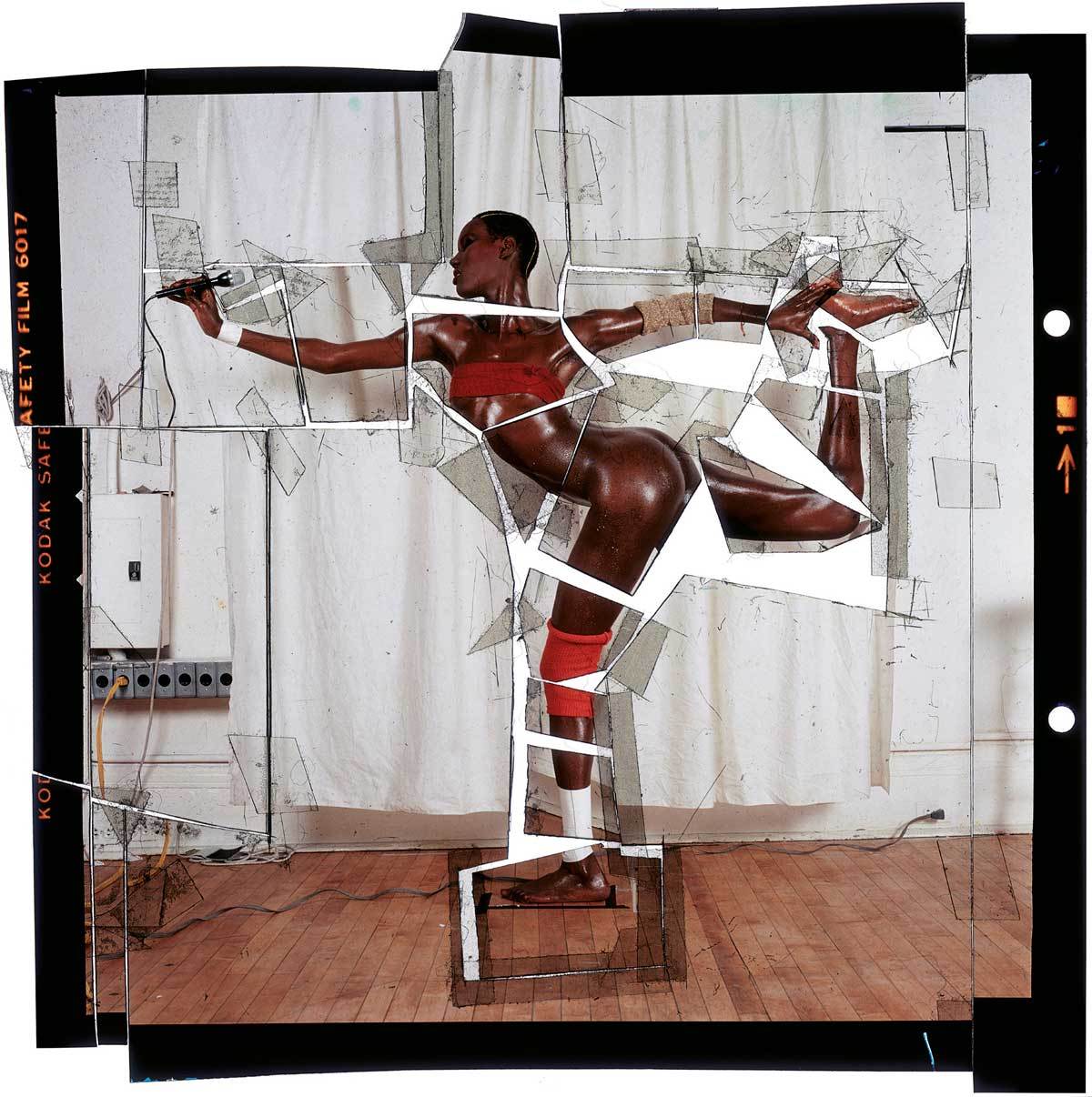

Her appearance was equally divisive — although her striking visuals led to her becoming a muse for the likes of Issey Miyake and Thierry Mugler, it provoked a bemused mainstream reaction, exemplified brilliantly in a 1985 interview which sees a confused journalist asking her to label her gender and sexuality (she pointedly responds by asking if he would eat a cockroach if he were starved on a desert island — he nervously admits that he would). This ambiguity was explored in extreme forms by Goude, who communicated this resistance to definition through the realm of post-production. “Slave to the Rhythm” opens with a brief sequence that sees a pair of hands chop, distort and elongate a Polaroid photo of Jones until her face becomes something more than human. In many ways, this is Goude’s translation of her outsider status — she’s not man, she’s not woman, she’s not even human.

However, it was Jones’ One Man Show that still reigns supreme as the purest incarnation of the duo’s creative vision. Nominated in 1984 for the first Best Long Form Music Video Grammy, the show is a combination of concert footage, photography and video clips, directed by Goude. The duo created other equally famous sequences, such as one that shows Jones sat, her face in profile view decorated with three geometric shapes attached by elastic bands.

An anonymous hand pulls the shapes slowly away from the face and cuts them away, while Jones barely flinches. This short clip more closely resembles performance art than a traditional music video, and encompasses the way that Goude’s involvement made Jones ‘more than’ a pop star. Her links with Pop Art were well-documented — she was famously close with Andy Warhol and renowned within the art world. Her visual credentials were more impressive than any of her musical contemporaries, and it was this element of high culture that made her contribution to the music industry so pivotal. She wasn’t a mere singer, and she wasn’t stereotyped because she resisted definition so fervently. There was always a sense that the music industry never quite understood Jones, a fact proven by the career complications that plagued her early work. Instead, she was a cultural phenomenon, and Goude’s work exaggerated and exemplified this.

By manipulating her image, he created the view that Jones was iconography in her own right — together, they built a legend that was instantly recognizable but drenched in mystery, whereas her personality and provocative soundbites helped fuel public interest not only in the singer herself, but in her relationship with Goude. Post-production, self-mythicization, and the exaggeration of her ‘exotic’ qualities were defined Goude’s work with Jones but also his career more generally — by electing and reifying a ‘muse,’ the artist helped create one of the most intriguing legends in musical history.

So Far So Goudeis at Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea in Milan, now until June 19.

Credits

Text Jake Hall