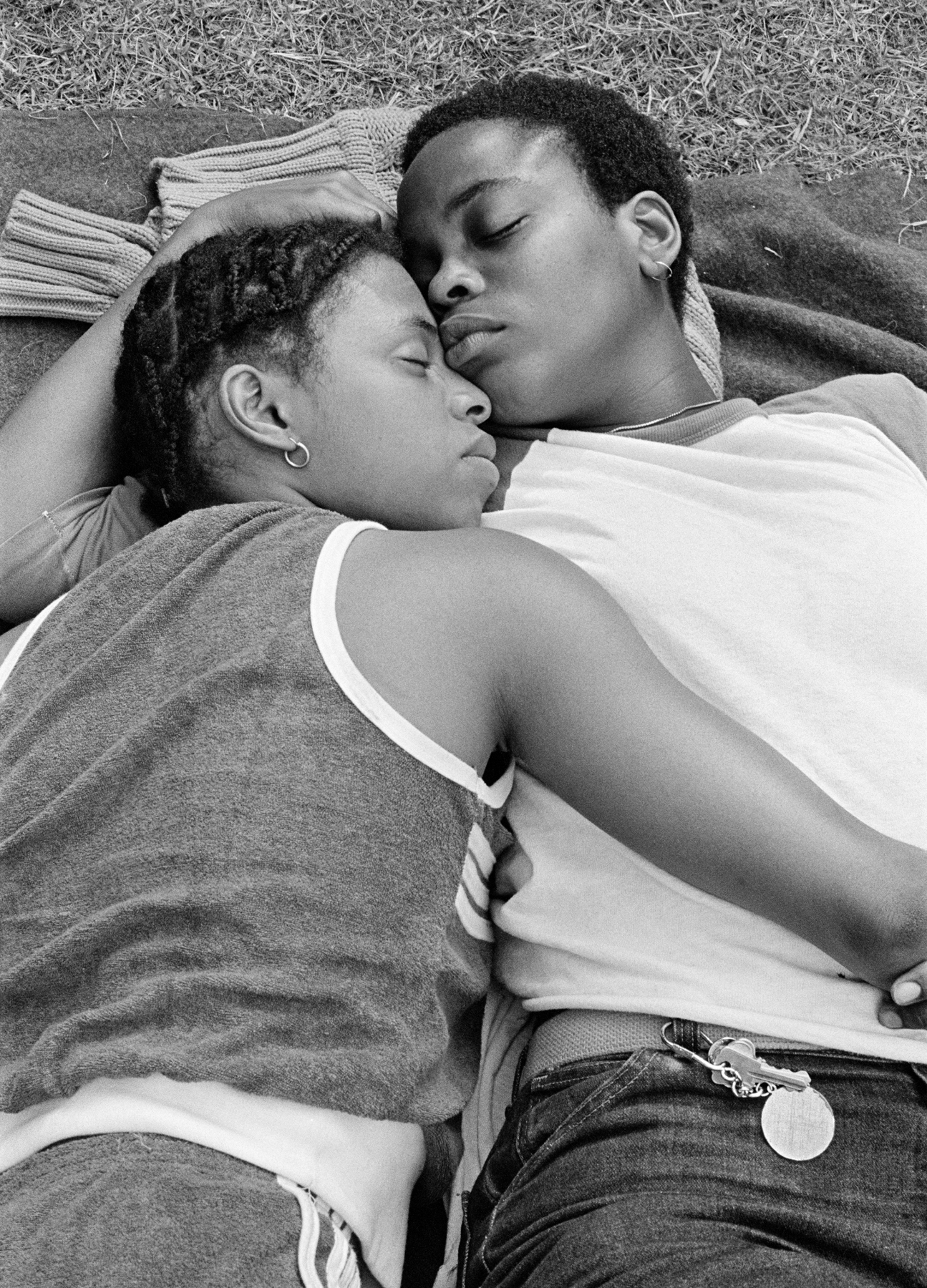

There was no known precursor to JEB’s groundbreaking 1979 self-published book Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians, a comprehensive and intimate study of lesbian life in America. Before making her own photographs, the spectrum of lesbian representation was what JEB, an activist and photographer, terms “fake or faux lesbians”. It was either “women who were young, slim, blonde, romanticised and gauzy, or vampire, man-eating pornographic stereotypes.”

Born in Washington DC, JEB (whose full name is Joan E. Biren) came of age during the heat of the Civil Rights Movement. She was always an activist but had no intention of being a photographer. Yet the hunger to witness herself in another’s image was too insatiable to ignore; she craved seeing a photograph of a woman kissing another woman. So, at 27-years-old, JEB picked up a camera to make that image with her then-lover Sharon, and went in search of more lesbians.

While the gay liberation movement gained traction in the 1970s, the toxic oppression of lesbians — and all LGBTQ+ people — remained. It was with great bravery that the women we see in Eye to Eye allowed themselves, their names, and their thoughts to be published at a time when being publicly outed often meant losing everything.

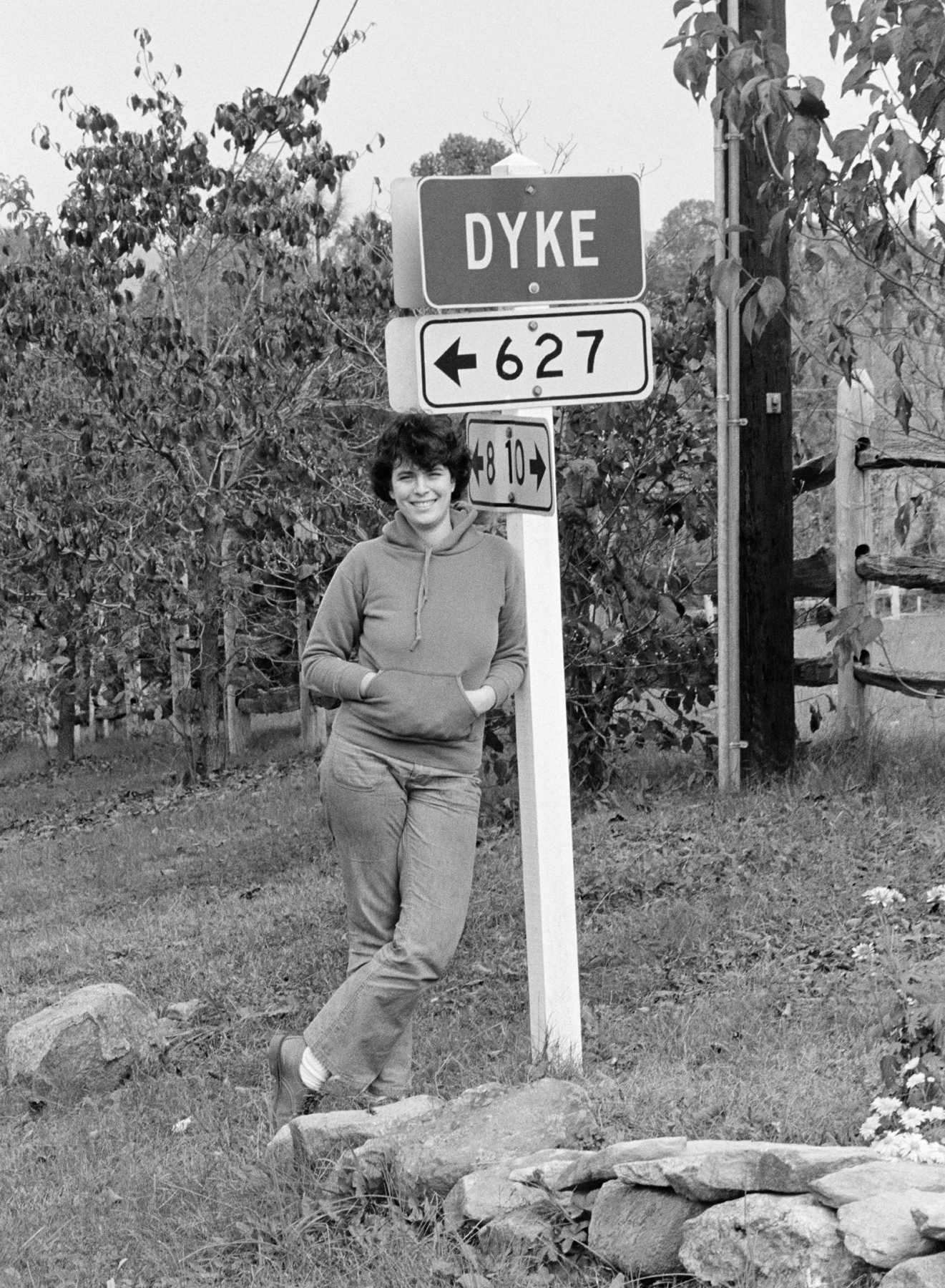

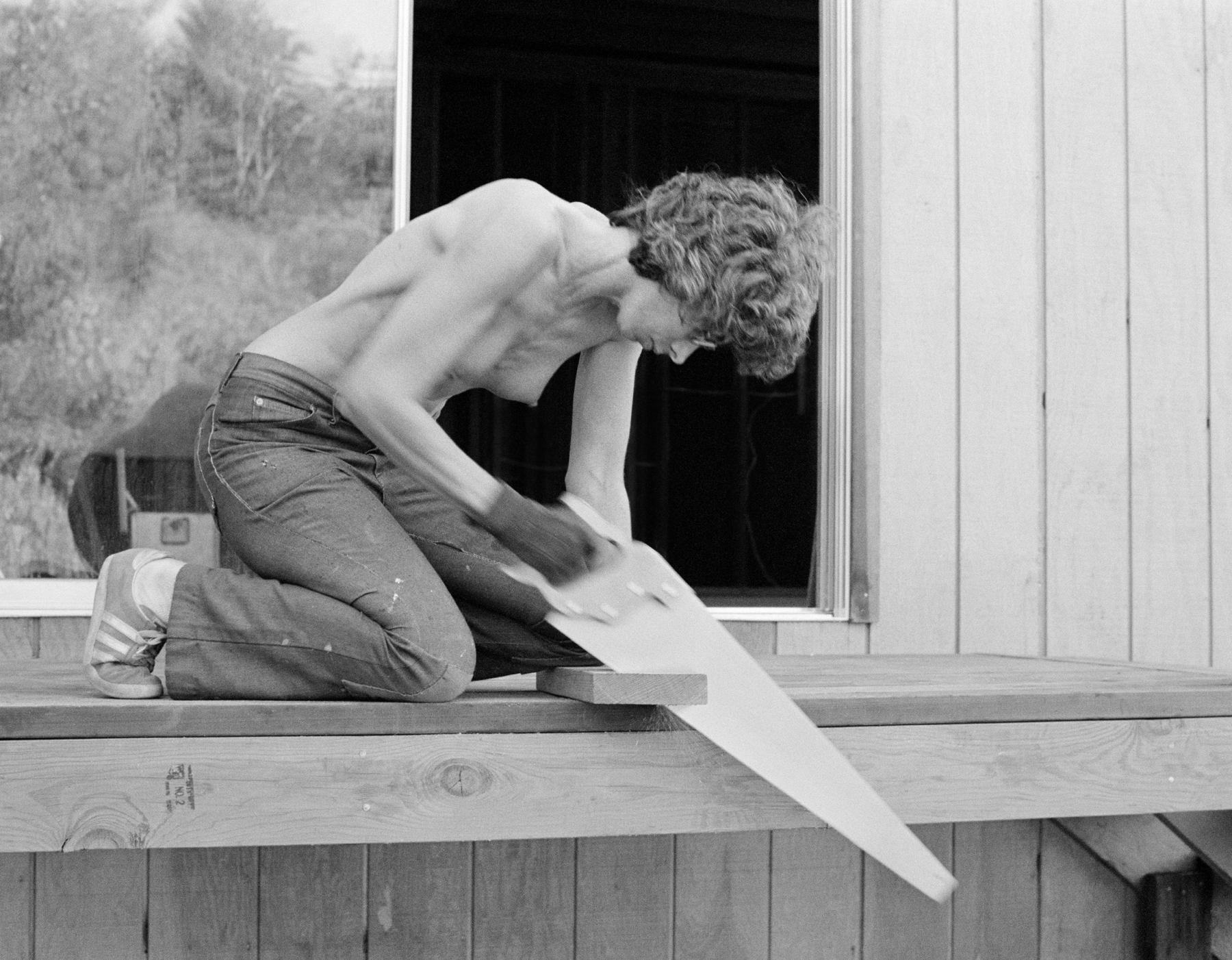

JEB used word of mouth to connect with lesbians of all backgrounds and ages. Travelling around the US, she made portraits with women at home, with lovers, with their children, at work, at rest, and in any other way she found them: living rurally or in urban cities, at music festivals, gay pride marches, and women’s conferences. She “made visible the invisible”.

“We didn’t have the word then, but my politics were intersectional,” she says. “I was determined to show as many different kinds of lesbians as possible. I wasn’t just going to have a book of my immediate friendship circle and community.”

The momentous reception that awaited Eye to Eye on its release demonstrated the burning desire for authentic representation. JEB published the images widely, in books and on postcards, posters, calendars, in newspapers, and exhibited in her touring “Dyke Show”. Women wrote letters thanking her for saving their lives, recalling how, after seeing her images, an unfamiliar feeling of pride overwhelmed them. Eye to Eye provided women with a mirror to reflect the possibilities of what they could be or what they already were.

More than 40 years later, Eye to Eye is being re-released by Anthology Editions. We caught up with JEB to speak about the importance of art as activism, the enduring appeal of Eye to Eye, and how her life could have been different if she had the same representation she created when growing up.

When you started making these images, what was lesbian representation like?

In the 19th century, Lord Alfred Douglas famously talked about the ‘love that dare not speak its name’. But in the 20th century, we were still ‘the love that dare not show its face’. Real lesbians have a very long history of exclusion and erasure, and because I couldn’t find authentic and affirming images, I became determined to make visible what was invisible.

My rallying cry was: ‘Lesbians are real people’. My work was made to counter the existing images and to be both redemptive and aspirational. To show us something authentic that we could find ourselves, our friends, and our lovers reflected in. Also something we could imagine ourselves to be if we weren’t quite there yet. A lesbian in Eastern Europe wrote to me and said: ‘We are made possible in the images you make.’

Many people talk about you being the first person to create authentic images of lesbians, but what was the first authentic image of lesbians that you remember seeing?

Truthfully, it was the first lesbian image I made myself in 1970. I made it because I so desperately needed to see it, and I couldn’t find it anywhere. That hunger for representation was something that I felt personally and very strongly [about]. At a deep level, I needed to see a picture of two women kissing.

When Eye to Eye was published in 1979, how were the images received?

My book’s response showed how enormous that hunger was in the lesbian community — the first printing of 3000 books sold out in five months. I made a second printing which sold out almost as quickly. Eye to Eye was number one on the LGBT booksellers bestseller list. It had an amazing reception.

Who did you make these photographs for?

I made the images very specifically and intentionally for lesbians. I didn’t think of anyone else when I was making the images or the book. My purpose was to give lesbians the representation that we didn’t have because our history had been hidden, destroyed and suppressed. The existing representations were not made of lesbians by lesbians. Eye to Eye meant we saw ourselves through our own eyes.

Is that what the title means?

It has many possible interpretations. At the beginning of the book, there is a quote from the Adrienne Rich poem, ‘Transcendental Etude’. The end of that quote is:

Two women, eye to eye

measuring each other’s spirit, each other’s

limitless desire,

a whole new poetry beginning here.

I wanted my book to be the beginning of a whole new visual experience.

You named Barbara Deming and Audre Lorde as mentors and friends. What was their impact on you?

It was huge. Barbara Deming taught me to be still and to listen. Audre Lorde taught me to be active and to speak out. I translated what I learned from each of them into the visual realm. Barbara’s ‘listening’ translated into seeing as much as I could of who we were, how we lived, loved, made families, and communities. To me, that was the foundation of making a movement.

Audre said, ‘Poetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought.’ Then she says, ‘There is only our poetry to hint at possibility made real.’ She helped me see that photographs could be like poetry, to make possibilities real for those who have not experienced them. If you see a Black lesbian, maybe you never imagined such a thing, which can give you the courage to dare to be what you want to be. It can move you to action. Audre’s words were galvanising.

Were you a photographer or an activist first? And how does that label ‘activist’ sit with you?

I embrace it completely. I keep trying to retire from photography, but I never want to retire from being an activist. I always had the drive to be an activist, and I never had the drive to become a photographer.

When I was in the radical lesbian feminist separatist collective called the Furies in 1971, I needed to find a way to express myself that was not what we called ‘polluted’ by what I had learned in the male-dominated educational institutions. I had a privileged education, and I was very good with words. That resulted from my brain being colonised by the patriarchy, which was pointed out to me by my collective members. I needed a new revolutionary tool that didn’t use words, so I learned photography. First through a correspondence course, then by working in a camera store, then by being the photographer for a small-town newspaper. When I started, I was 27-years-old. That’s when my drive to become a photographer happened.

Was it challenging to find women to make photographs with for Eye to Eye?

When I started, it was very hard. People ran away from cameras. To even put first names and places like I did in Eye to Eye was a big deal. The fear of being identified as a lesbian publicly was justified. You could lose custody of your children, be fired from your job, be deported, ex-communicated, disowned by your family, and so much more. So I want to emphasise that, without the courage and the willingness of these brave lesbians who agreed to be photographed by me, and who trusted me, there would be no Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians. I am so much in their debt. I admire them all so much, and I thank them all so much.

What impact would seeing images like yours have had on you as a young woman?

It’s speculation, but if those images already existed — and I didn’t have to make them — I probably wouldn’t have become a photographer. Maybe I would have come out sooner. Maybe I would have had a much higher opinion of myself. Maybe I wouldn’t have had to join a 12-step programme. It’s impossible to say exactly how, but I think my life would have been entirely different. That’s why I believe in the transformative power of art, and why art is activism, or why it can be.

What significance do these photographs hold 40 years on?

Everybody always makes their own significance when they look at an image. You can know what it means to you, but anything can happen once it leaves your control. When I first published Eye to Eye, there was so much homophobia and censorship that public access to my work was limited. Now that the work will be widely available, I’m very excited because it can find new audiences who didn’t know the work, and they can see that lesbians did exist, live and love at that time, when they may not be aware of that.

Photos from ‘Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians’, published by Anthology Editions.