“We really thought, in the 70s and particularly in the summer of 66, the millennium had arrived,” Roger Steffens, a California creative icon once referred to as “The Forrest Gump of LSD,” told me last year. “The world was really going to change forever; it was going to be filled with love and sharing and creativity and communal living. I mean we honestly believed that shit.” We were talking about his long, strange trip through the 1960s and 70s — punctuated by a 26-month-long deployment in the Army’s psy-ops unit during the Vietnam War. When he returned, Steffens captured one of the most transformative periods in American history — California’s counterculture — through a trippy, technicolor lens. Steffens shot the hippie fairs of Mendocino, protests in Berkeley, and endless blue skies in Big Sur. Recently, Steffens’s personal photographs have filled books and gallery exhibitions under his family’s collective art-making moniker, The Family Acid. And in the process, he’s given post-baby-boomer generations a new view on the urgent cultural politics behind what’s so often dismissed as half-baked flower power.

That’s precisely what the major new exhibition Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia, opening tomorrow at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, explores. Except instead of an LSD-laced family album, Hippie Modernism pulls together an immense variety of experimental furniture, alternative zines and books, historic protest posters, immersive installations, and documentary photography. Together, these archival materials and artifacts provide a wholly unique portrait of radical, revolutionary times. It’s the first comprehensive museum exhibition to show how these alternative communities and the boldly experimental art, design, and architectural practices incubated within them challenged the social, cultural, and political status quo.

The exhibition displays Ira Cohen’s iconically psychedelic images of Jimi Hendrix — manipulated with mylar mirrors — alongside documentary snaps of the gender-irreverent Cockettes, the theater troupe of acid freak drag queens formed in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood in the fall of 1969. Despite existing for less than three years, The Cockettes are still subjects of reverence and legend; last month, Nan Goldin and Glenn O’Brien swapped stories of witnessing their gobsmacking gritty glam. Equally trippy: John Coney’s 1974 Afrofuturist opus Space Is the Place will screen during Hippie Modernism’s film programming. Shot in Oakland, the super-saturated sci-fi film was inspired by a series of lectures its star, Sun Ra, gave at UC Berkeley.

And in placing a special focus on its Northern California home, Hippie Modernism demonstrates just how future-forward the Golden State’s thinking was (no wonder there’s serious talk of secession from Donald Trump’s divided states). “In the Bay Area, many hoped to go beyond mere critique to create actual change — technological, political, and ecological — on the streets, in the classroom, and in government policy,” reads the exhibition’s press release. “In the art, architecture, and design of the counterculture one can see early stirrings of the tech revolution and ecological consciousness, as well as powerful expressions of the desire for peace and social justice.”

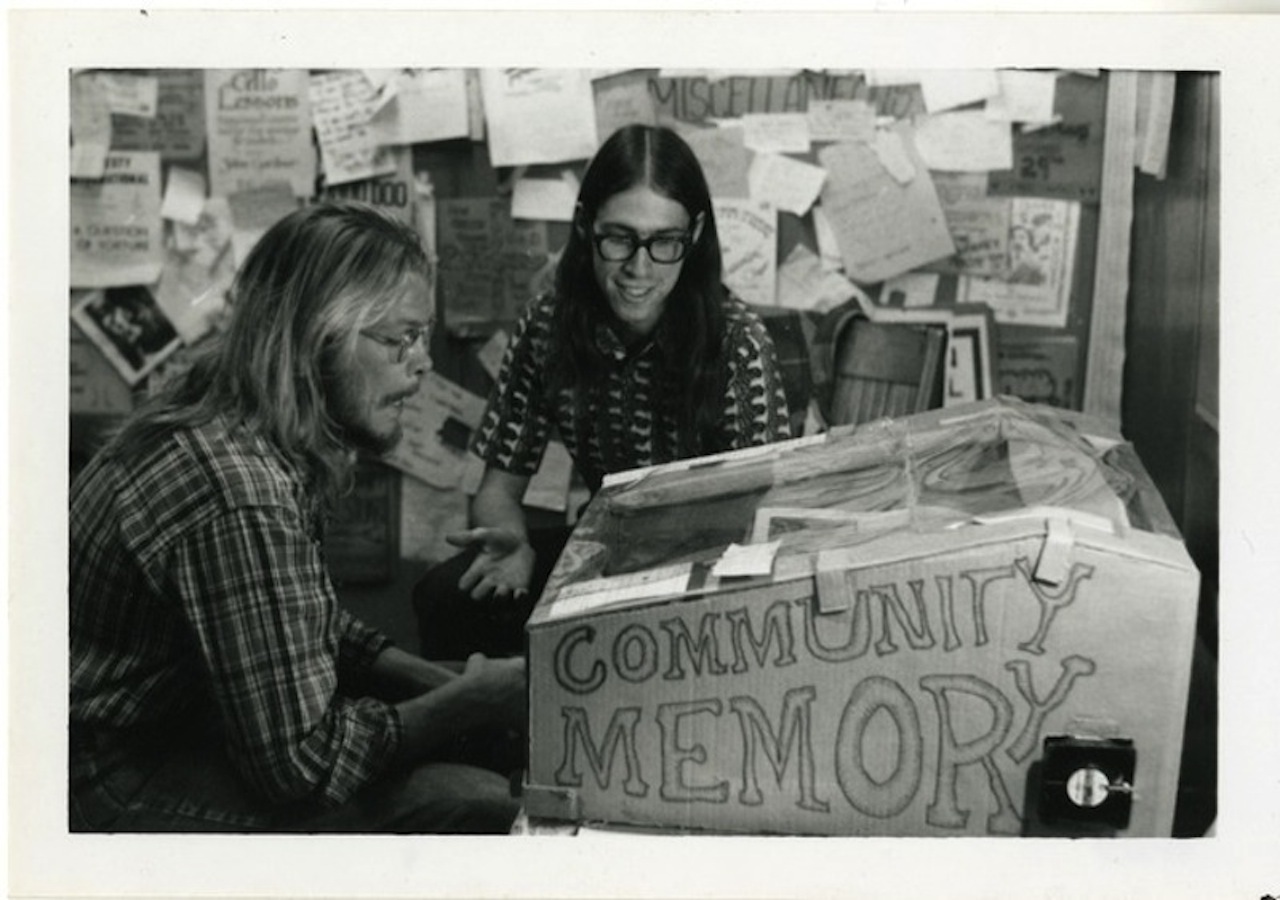

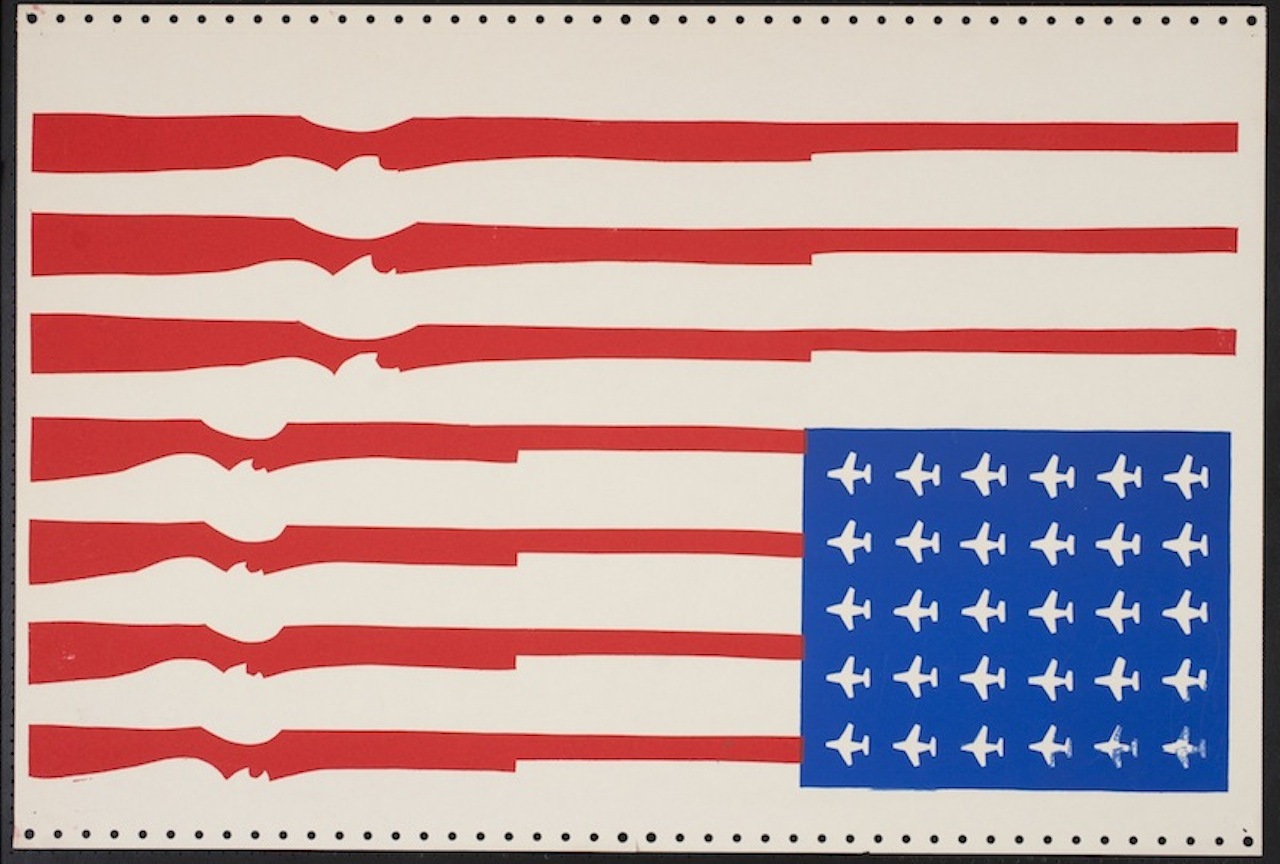

For example: Hippie Modernism features documentation of “Community Memory,” a computerized public bulletin board system established in Berkeley in 1973. Effectively, it was one of the first-ever digital social networks. There are also several images from Handmade Houses. Published the same year, in 1973, the book by Art Boericke and photographer Barry Shapiro is an enduring record of Northern California’s owner-built homes that precipitated our current movement towards more sustainable living. Hippie Modernism also pays tribute to the region’s rich history of social protest. There are archival art materials from Bay Area resistance movements and collectives, including the Indians of All Tribes’s occupation of Alcatraz, the Griffith Park Gay-In, the Chicago Women’s Graphics Collective, the Mexican-American Liberation Art Front, and the Black Panther Party.

And if you’re in the Bay, it’s worth checking out the BAMPFA’s public programming lineup. In addition to the more traditional gallery tours and forums, there are also analog light show workshops (where you can play with old overhead projectors, colored transparencies, and prisms) as well as kids fabric collages and a conversation with author Michael Pollan about promising new therapeutic uses for psychedelic drugs. There’s even a family photo album day, for which visitors are encouraged to bring in home movies, posters, pictures, and flyers from the 1960s and 70s. It’s bound to be the trippiest show and tell ever. Maybe Steffens will stop by.

‘Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia’ is on view at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive from February 8 to May 21, 2017. More information here.

Credits

Text Emily Manning

Images courtesy of Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive