Fashion and the Catholic Imagination is the subtitle to the Met Museum’s upcoming exhibition, Heavenly Bodies. An exhibition that, from the promo materials, promises to deal in all your favourite blockbuster Catholic fashion cliches; crosses and crowns of thorns, incense and guilt, the power and the glory. Plenty of Our Lady’s but not a lot of Madonna. The images released so far evoke an ornate literalism of theme; fashion inspired by priestly silhouettes and devotional imagery; and the Catholic’s love of luxurious iconography and use of beauty and history to instil faith. Heavenly Bodies is the Fashion/Catholic axis represented as a pure thing of sensual splendour.

But what about the big bloody mess of the rest of it. What about fashion’s equally strong rebuttal of all this worship? What about fashion’s defiling of the hallowed, and its rebellious anti-Catholicisms? Heavenly Bodies promises not to explore fashion’s habit of careless cultural appropriation of other religions, either. Why should it? Well this is an area full of exciting, provocative statements that reach beyond the Fashion/Catholic orthodoxy, to find some deeper narratives and expressions. It would be a totally different exhibition of course, so this is not to criticise Andrew Bolton’s curatorial choices – I am also, after all, a good Catholic boy, who loves a bit of Catholic fashion – just to offer some kind of counter to it all. And the exhibition does promise to be a feat of curatorial majesty: holy garments blending in with the work of the expected (Versace et al) to the more surprising; Raf Simons to Demna Gvasalia, from the Tunisian Alaia to the Japanese Jun Takahashi.

No major religion has been spared fashion’s lurching egotistical desire to desecrate the sacred in the name of serving a dramatic look. In the last few years we have become, generally, more understanding of, and less accepting of, cultural appropriation. Yet every season we are bound to see some bad religious drag turning revered spiritual touchstones into fashionable trinkets. So why is fashion so obsessed with religion when it so easily causes such consternation and offense?

The root of it is found in the deep links between Catholicism and fashion in Europe — a creative flowering, fashion sprung forth in the shadow of denominational mysteries. An axis of devotion that takes in the various Catholic heritages of Cristobal Balenciaga in Spain and John Galliano in London. Jean Paul Gaultier and Coco Chanel in Paris and Else Schiaperelli, D&G and Versace in Milan. And so fashion has turned to — because that is what it knows — Catholic ritual and the clerical silhouette, reaching for them to provide spiritual permanence in the industry’s seasonal cycles. These are all incredible designers of course, and have each in their own fantastically creative and different ways defined the modern fashion world. From their backgrounds, they find themselves taking in, quite naturally, Catholicism’s parade and pomp and drama. Find theme from Catholicism’s luxury and iconography, from its Baroque opulence and devout monastic austerity. Even the Pope, for a time, was wearing a pair of red Prada slippers.

If this is the natural order, then when fashion has looked further afield, beyond Europe, it’s often been in the misguided service of providing an aura of discovery, an air of worldly wisdom or a crutch of easy exotica. It is from this, that we so easily slip. Easily accused of cultural appropriation, insensitivity. Yet, sometimes this all meshes into something beautiful, something that opens up possibilities.

Take just this season for an example. Marine Serre’s collection was incredible. At its heart was the symbol of the crescent moon. Her use of it plays upon the power of a symbol demonised by its association with Islam, reconfiguring it as part of her “radical call for love”. A desire to universalise, understand, promote empathy. In tandem she also explored whole body coverings, turning a look that at shorthand says conservative religious restriction, into a resplendent sporty freedom. It is in these kind of inversions, reversions, and opening-ups that fashion finds something more interesting to speak about than merely the replacing of devotional imagery as print and shape.

The other side of this show of multicultural unity came from Gucci, who drew ire from some for their use of turbans in their autumn/winter 18 collection. Alessandro Michele was aiming for a collection that showed the things that links us together; a beautiful fashion possibility offered by a cross-cultural jumble, free of restriction.

But no matter Michele’s good intentions, it backfired. The Gucci turban ended up coming down the runway on a white model, which most saw as offensive. It was meant to be — and in general the collection was — an exploration of the power of being liberated of the codes of dressing; a fashion utopia free of gender, race and religion. So the turbans featured alongside lavender coloured lace burka-allusions and printed silk babushka headscarves, it contained fair isle knits and baseball logos. Unfortunately we do not yet live in a fashion utopia, for some it only ended up highlighting the restrictions still felt by many.

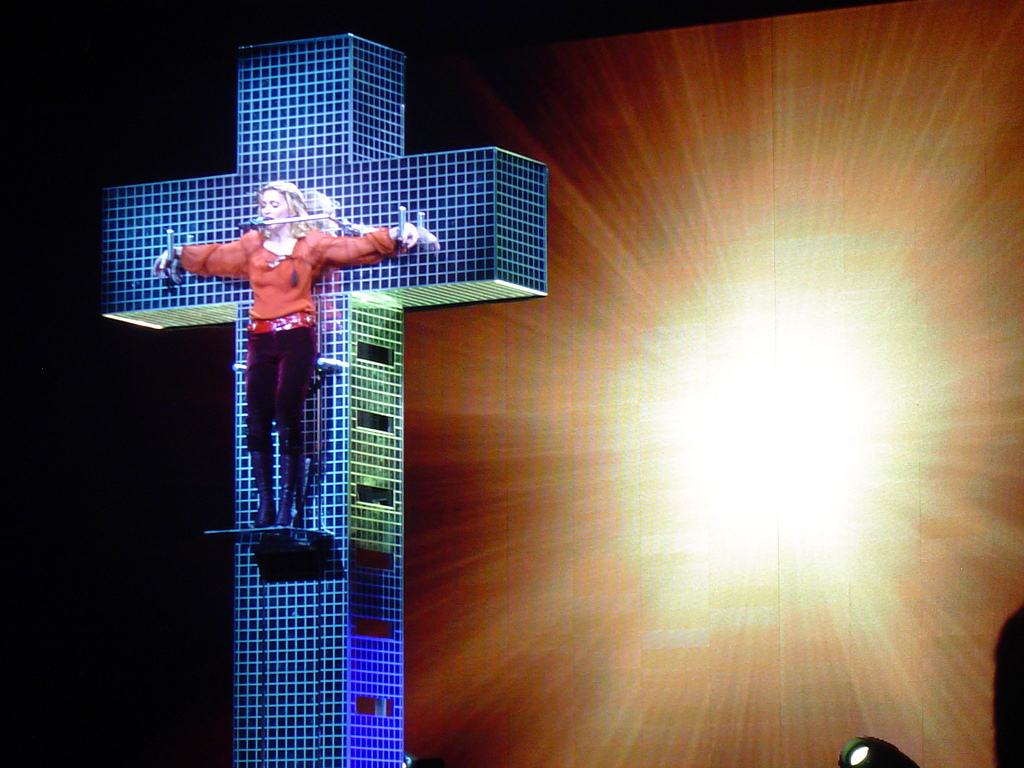

It’s less controversial in fashion these days to break down the gender binary than the one that separates the flock from the pagan. And yet fashion continually tries to. Whether in misguided desire to spread peace, love and understanding, or just iconoclastic provocation. It relates to power, back to that old fashion-Catholic orthodoxy. Rick Owens can take inspiration from nuns’ habits for spring/summer 09, Givenchy can make necklaces to resemble crowns of thorns and D&G can reference the mosaics of Sicilian cathedrals. Galliano, for his autumn/winter 00 couture collection, famously sent a look down the runway that was full on priestly garb. These draw little criticism, except from the most reactionary of Catholic blowhards, because these attacks/satires/reversions/tributes come from people in positions of power, against those in power. There’s no exploitation.

Yet when it looks abroad, obviously, that power dynamic changes. Fashion’s litany of accusations of cultural appropriation spare no-one. From Yves Saint Laurent’s orientalist Opium collection of 1977, to Galliano’s Dior Couture of 1997, which riffed on Pocahauntas. Alexander McQueen has found inspiration in African Yoruba jewellery, and Balenciaga made a very high fashion version of Palestinian Keffiyeh under Nicolas Ghesquiere.

Two famous historical shows to consider. Firstly, Jean Paul Gaultier’s autumn/winter 1993 show Chic Rabbis, which turned orthodox Jewish wear into haute couture. A hasidi-drag of women walking in traditional male Rabbinic attire. It featured reinterpretations of Shtreimel (large fur hats), thick streams of black cloth, models walking down a menorah-lined runway. To simplify and reinstate: the question here circles around who is reinterpreting what. Gaultier can use Catholic imagery in his collections because he’s a Catholic. You can’t elevate oppression to fashion.

Yet, how about Chalayan’s infamous Burka collection of 96? An elaborate yet simple play of revealing everything / showing nothing, seen through the restrictions of traditional Islamic wear. A liberation or a desecration? That is some cryptic power at work in that most famous image, of six women lined up, the one of the furthest left completely naked, furthest right, completely covered. Chalayan’s show has retained its power because it provides no easy, glib answers, or one-size-fits-all cultural reductions.

One woman’s freedom is another’s decadence. One designer’s tribute to the polyphony of identity and the diversity of religion is someone else’s grossly offensive slur.