R.L. Stine didn’t invent the teenager. But for a generation of young people coming of age in the 1990s, whose earliest scares arrived via pulpy teen horror novels you couldn’t believe your parents were actually letting you borrow from the library, he basically did. Stine’s placid, plastic suburbias, with their neat lawns, inevitable serial murderers and WASPy teen inhabitants, were worlds away from the kinds of lives actual teenagers were living. But they nevertheless managed to stake a firm and only vaguely irresponsible hold on readers entering puberty in or around the last decade of the 20th century — worlds and adolescent personas that we expected to someday inhabit, and tried our hardest to will into existence.

Goosebumps is arguably Stine’s most famous creation, but it was also an anthology horror series strictly for the kindergarten set, all gloopy ectoplasm and gross-out. Fear Street, his most enduring YA anthology series was comparatively adult. There was occasional murder, mild swears and PG-13 sex, in the process introducing a generation of kids to the soapy dangers of sexual obsession, unscrupulous step-siblings and deep-seated rivalries.

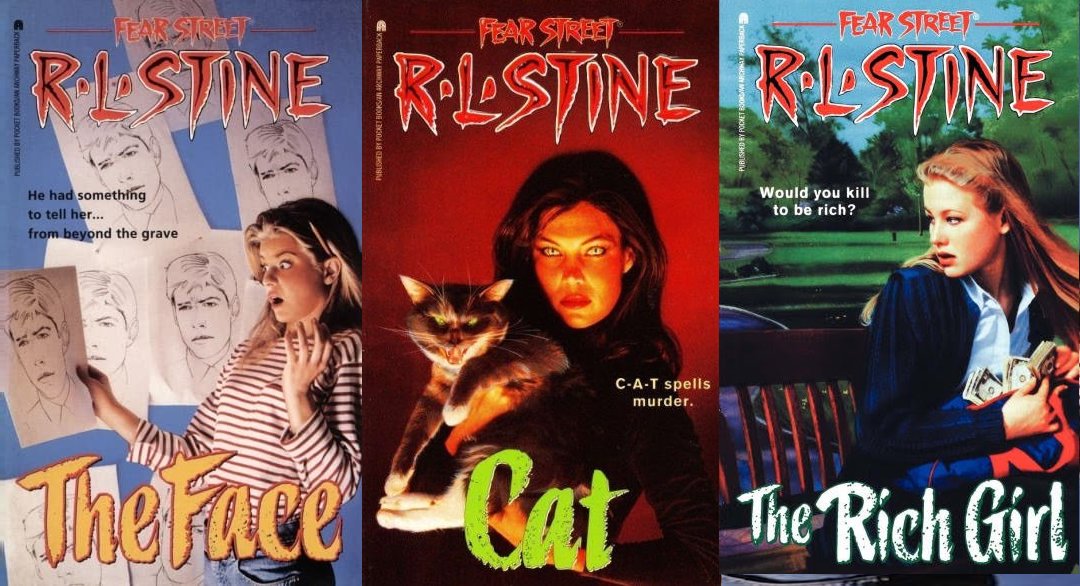

Launched in 1989 and set in the fictional town of Shadyside, the Fear Street series ground down American adolescence to its most generic signifiers — jocks and cheerleaders, cliques and shopping malls, girls hyped for prom and boys riding motorcycles — then added violence. For the most part, Stine seemed to work from a title backwards, centering his stories around easily-relatable high school threats that took the form of, say, your boyfriend or girlfriend, the rich girl in class, the evil cheerleader, or the psychotic boy next door. While some dipped into the supernatural (notably the body-swap classic Switched), the majority were resolutely earthbound, revolving around stalkers, spurned exes or jealous BFFs.

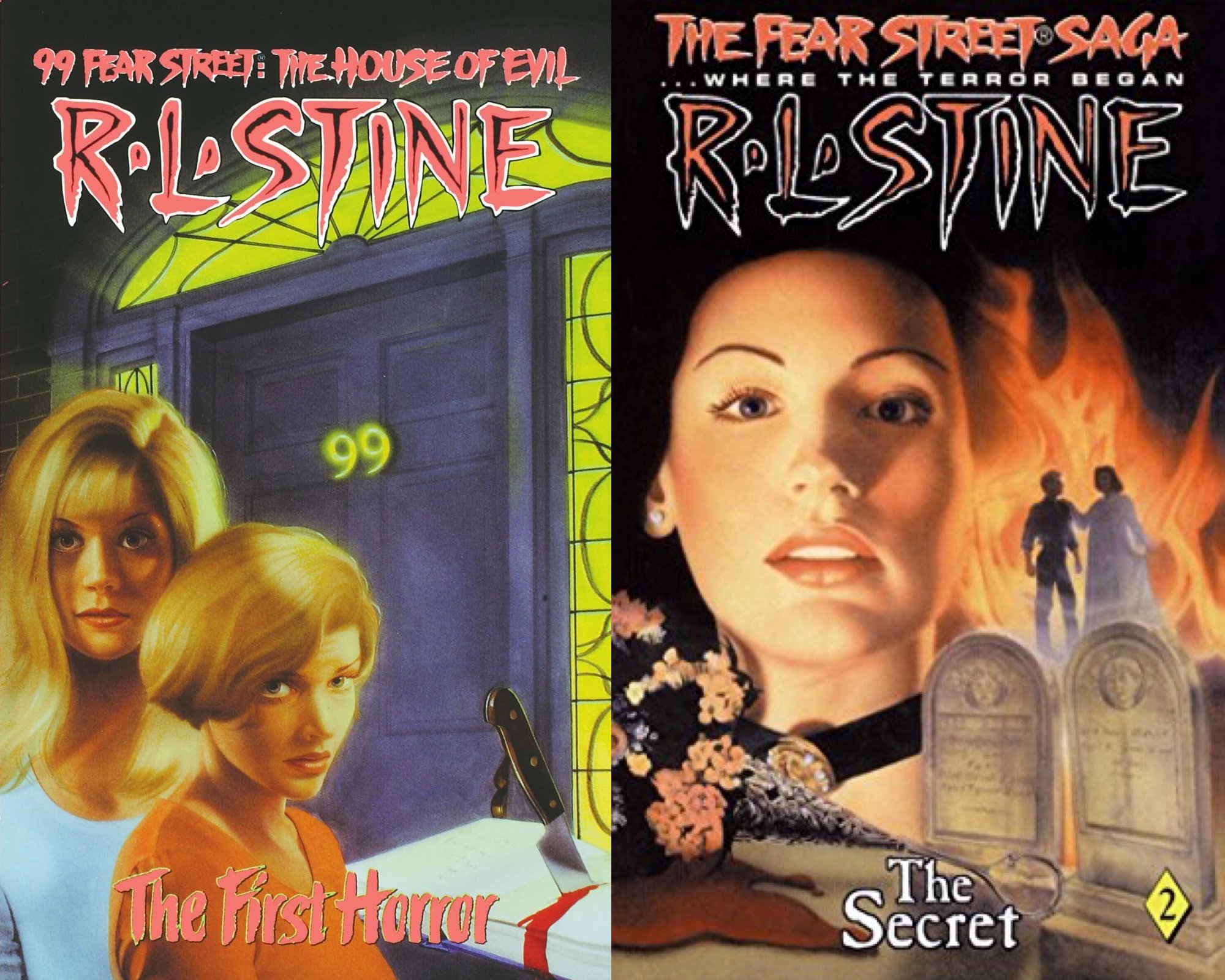

In the wake of the brand’s cancellation in 1999, Fear Street titles were mostly confined to some of the dustier shelves at used book stores, waiting in vain to be re-discovered by a generation who had already become well-versed in sex and slasher horror not from YA novelists but from the internet and cable TV.

But Fear Street has also undergone an unexpected resurgence in recent years, one spearheaded by one-time fans, leading to Stine returning to the series for a revival that launched this summer, the development of a feature film based on the series, and the launch of Teen Creeps, a popular comedy podcast celebrating the Stine oeuvre and works by fellow YA pulp maestros including Christopher Pike and Lois Duncan. Hosted by comedians Kelly Nugent and Lindsay Katai, the show dismantles the well-worn cliches and gonzo plotting of the genre, while celebrating the unusual nostalgic pleasures they continue to inspire.

“Once you reach a certain age, you’re kind of like, ‘Oh, I need to get away from the real world and go back to a time when the most stressful thing was middle-school stuff,’” Nugent says. “I mean, middle-school sucks, but this type of genre, which is gory horror for teens, is all, ‘I don’t have problems, these people have problems – like there’s a killer on the loose and he might be my boyfriend!’ The stakes are so high that it makes everything else fall away.”

Nugent’s own Fear Street journey isn’t unique among Stine fans. Having outgrown Goosebumps, she discovered the Fear Street series while venturing around the library near her house, pulled in by the promise of high school sexiness and the books’ many compelling, if ludicrous, taglines (“C-A-T spells murder,” screams the perplexing cover for 1997’s The Cat.)

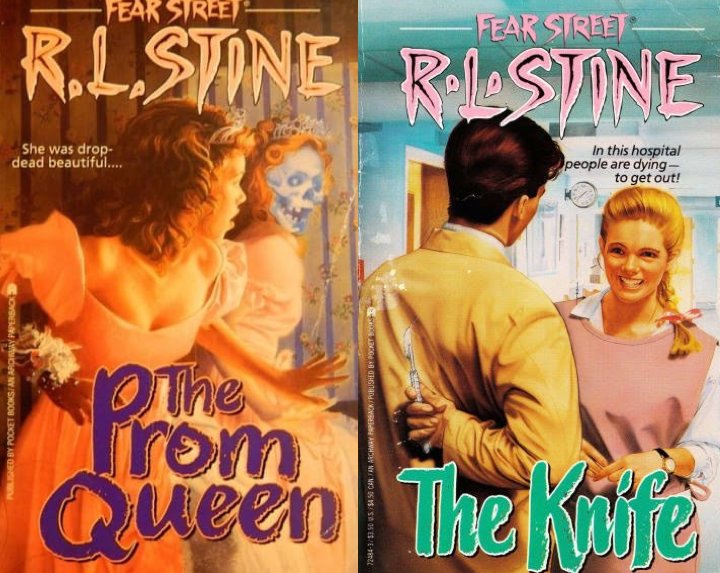

The artwork itself helped. Arguably the series’ greatest legacy, Fear Street’s cover art remains campy and Tumblr-friendly to this day. Comprised of photo-realistic illustrations, they merge the lurid, dangerous aesthetics of classic pulp with pretty cover models dressed up in 90210 fashions. Colors are blindingly saturated, the girls all sport over-plucked eyebrows and pastel sweaters, and the boys all resemble Joey Tribbiani. The fact that they all look at least 35 only adds to their nonsensical charm.

“I remember being titillated by them too,” Nugent says. “When you’re like 11 or 12, you’re very, ‘Ooh, there’s like butts in this… and also blood!’ They also painted this poppy image of what high school was gonna be like. Like I remember thinking to myself, ‘God I wish I could just do what normal girls do.’ And in my mind that was like, hang out at the mall, flirt with guys, and get involved in hijinks and adventures. But then it made the real world just seem like such a mundane version of that.”

Adds Katai, “You know the Gingham filter on Instagram? Everything felt like that, where it was just a muted, banal version of Fear Street. It was not exciting. I thought that everyone would look a lot better too, but we just all looked horrible. In these books the guys are all named Blake and they all have muscles and they surf and they ride a motorcycle, whereas the guys that I was actually seeing around school were like, tall and gangly and could barely keep weight on.”

While Fear Street inspired chronic adolescent disappointment for many of its young readers throughout the 1990s, revisiting the series as an adult can be its own special sort of fun, if shocking when it comes to their thoughts on sex and gender. Many of Stine’s male characters are creeps, whether they turn out to be murderers or not, with emotional or physical abuse depicted as an everyday by-product of teenage dating. In 1997’s What Holly Heard, the female lead’s decision to stay with her violent, steroid-abusing boyfriend is written as a romantic, happy ending, while body weight serves as a recurring Fear Street plot device almost as much as dreamboat love interests are described as looking like Tom Cruise.

“It made me realize how much of that I must have been internalizing as a teenager,” Katai says. “I think in every one of these books, the truly toxic message that we were getting was ‘boys will be boys’, and to forgive that because they can’t help it. And the fact that I didn’t even recognize how insane and insulting that was says a lot. But also most of these books were being written by men, and we’re not getting a female voice.”

Today, both women agree that they wouldn’t necessarily support a pre-teen girl reading the Fear Street series, particularly if she’s inclined to take things at face value. They do, however, argue that there’s something inherently positive about reading the books as adults, enjoying them for their silliness, but ripping them apart when necessary.

Adds Nugent, “The reason I still enjoy reading these books is that now I feel, and I know it sounds weird to think that you have power or status over a book, but since we’re like enlightened or whatever, we hold the cards now, we have the power, because we’re going to take it all down a notch.”

It’s also something that the recent Fear Street revival seemed to recognize. Published not by a YA imprint but by Harper Collins, and bearing throwback cover art mirroring the pulpy promotional imagery for Stranger Things, the new books appear to prioritize nostalgic adult readers over a new generation of pre-teen horror fans. It makes a certain kind of sense. For all their moral weirdness and occasional toxicity, Fear Street stories are also literary comfort food – big, dumb thrillers blissfully devoid of complexity or shades of gray.

And while their adolescent appeal stemmed from their heightened high school drama, the easily-guessable whodunits and all the Christian Slater references, it’s almost the reverse today, where their generally low-key stakes come as a relief. It’s very easy to spot a through-line between the revival of Fear Street and, say, Charli XCX’s 1999, which grasps for the simple pleasures of pre-millennium life, or at least the parts of it that were aesthetically pleasing.

In a political climate inspiring of little but despair and rage, and the planet widely believed to be on its last legs, sometimes the most important form of literary self-care is reading about a jealous love rival wrecking the school play and pushing a wardrobe onto one of its leading ladies, as in 1996’s The Secret Admirer. And then giggling over how silly it all is.

“It’s cathartic,” Katai suggests. “It goes back to like Greek theatre and tragedy, where a huge aspect of it was the cathartic moment in the play. Maybe it’s like how Shirley Temple movies were really popular during the Depression. Like, ‘There are so many wars – let’s just watch a baby tap-dance.’”