i-D Hair Week is an exploration of how our hairstyles start conversations about identity, culture and the times we live in.

Like many other young women, the first thing I learned about my body as a 13 year old was how to conform it to society’s standards. And in addition to being obedient and having a knack for cooking and housework, society expected me to have a hairless, thin body. Because I grew up in Turkey, where women are still devoted to ancient waxing practices, the rite of passage didn’t come by way of a candy-hued, friendly Venus razor. It came through a one-inch thick disk of clear, amber-colored hard wax, warm and sticky—a far more vengeful goddess than its Western counterpart, as I was later to find out.

Prior to our yearly seaside vacation, my mother pulled me aside and told me it was time I learned how to remove my body hair by myself, so that like her (and every other “orderly” Turkish women) I could practice it every month. She stuck the wax on the left side of my pubic bone, told me to take a deep breath, and pulled it up. Burning with anger, pain, and fear, I ran away. It felt like my body had betrayed me by producing this hair, which now had to be taken care of, and my mother further betrayed me by intentionally hurting me. I spent the following month chuckling at my half-waxed pubic hair, which felt like a small victory—a private rebellion.

In many Middle Eastern countries, this simple sugar wax is made at home. The recipe includes sugar, lemon juice, and water, is edible, and often euphemized with names like “honey”, “resin”, or “caramel”. (Nadine Labaki’s charming 2007 Lebanese indie about an Almodovarian beauty parlor story is called Caramel.) My generation grew up with nostalgic stories of waxing as a communal event—in the old days, women in the same family would gather once a month to wax together in someone’s apartment, where no males over the age of six would be allowed. According to one Orientalized narrative which literally gave me goosebumps, in the Ottoman harem, women would only leave their hair, eyebrows, and eyelashes, waxing everything below the neck every three weeks—as Muslim culture links body hair to hygiene. Aliya*, a 27 year-old Lebanese photographer I brought up the subject with seemed to agree. “I don’t agree with body hair stigma as it pertains to arms, legs, or even pubis, but if it’s body hair located in an area that generates a lot of sweat, such as your armpits, then you should remove it, regardless of gender,” she said. Although she has lived in New York since 2013, “I have a lot of male friends in Lebanon who shave that area,” she quickly added. “My sentiment is probably a product of my cultural upbringing.”

What I didn’t know in 2001 was how the image of half-waxed pubes was going to be emblematic of my lifelong relationship with my body hair as a Middle Eastern woman who grew up in a Muslim culture. I spent most of my adult life thinking removing body hair did no particular good for me: It invariably hurts me and it costs me time and money. But having been born into a culture where gender roles feel more strict than they do in the West, where women are expected to be feminine, I could never stop waxing all together. I spent my mid-teens to early 20s obsessed with body hair—so much so that a single strand anywhere on my body was out of question. I spent hours spread on waxing tables in beauty salons, equally enchanted and weirded out by the intense relationship between the wax lady and her clients. My early 20s found me as an exchange student in Scandinavia, where I first read about body positivity in feminist theory, which links acts like waxing to internalization of misogynist ideals. I related to it more than almost any other feminist discourse I had previously encountered and grew out all my body hair for a few months—for the duration of the semester. However, as soon as I returned to Istanbul, I went back to waxing immediately, as if my newfound ideals had evaporated on the flight back.

Turns out I am not the only one who has been spiraling. “In all honesty, it’s an evolving relationship—I’ve oscillated a lot over the years,” Fariha Roisin, a queer Muslim writer recently said of her relationship with her body hair. “In my early queer days, it was easier to feel liberated with body hair— the subversion aspect of reclaiming something that’s been wildly restricting and toxic. But, these days I enjoy waxing my legs, or pussy, underarm, too. It’s overly simplistic to say dating men (cis or trans) means I should present a certain way. Yet, it’s really about how you wish to present yourself at a moment.”

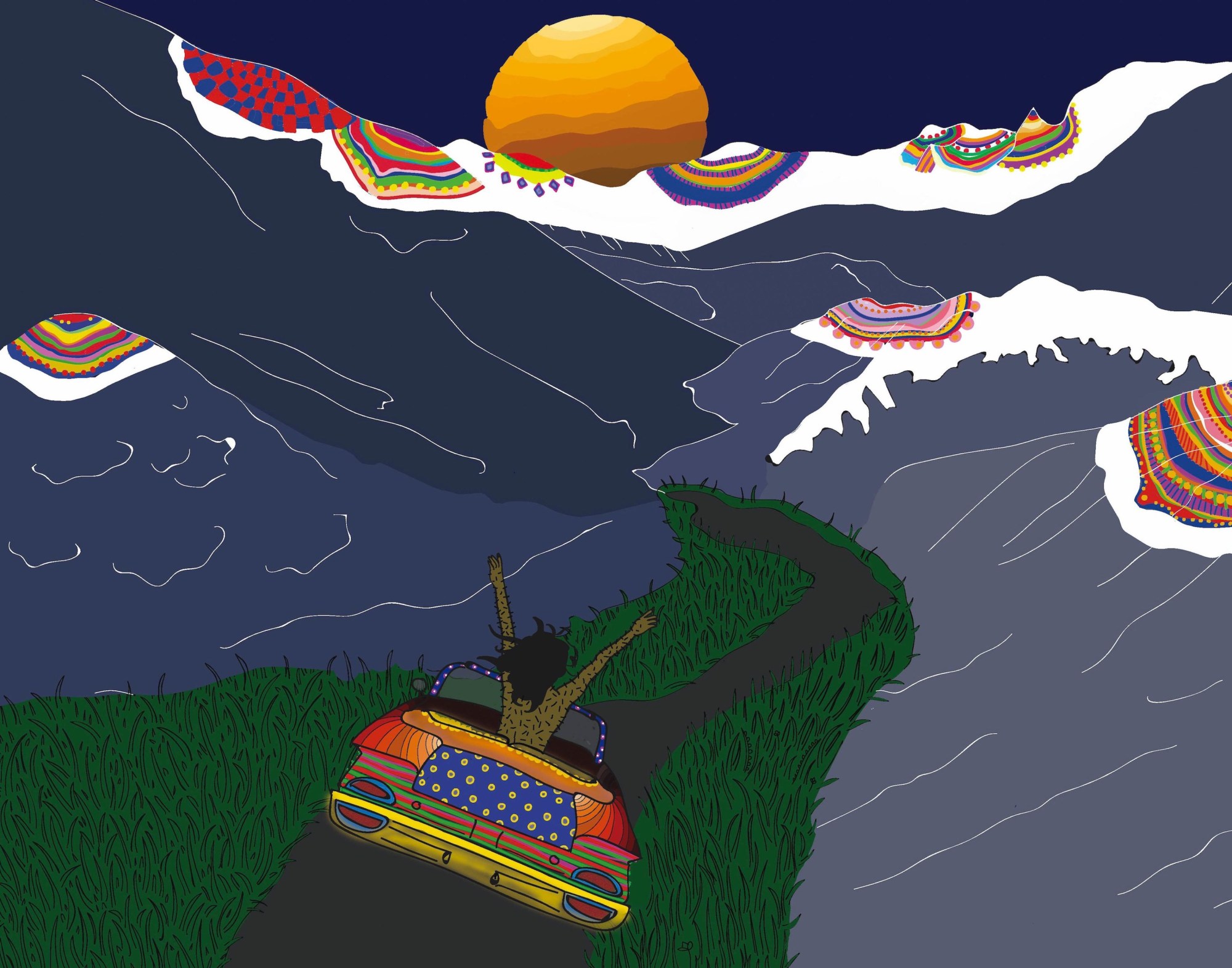

In the recent years while I’ve lived in New York, armpit and pubic hair have become increasingly more acceptable and en vogue for white women. From American Apparel’s pubic hair mannequins to a conscious flaunting of body hair by everyone from Madonna, Miley Cyrus, Grimes, The Ardorous women and Alexandra Marzella, it’s a trend/statement that arrived and stayed. Encouraged by it, I let go of the West Village waxing salon I had frequented in my early New York years, and went into another growing cycle—this time, while working for a fashion magazine. All this while, I kept wondering when body hair would be an actual conversation among Middle Eastern or Muslim women. Turns out, with the exception of Ayqa Khan, a Pakistani-American photographer and illustrator, the answer is close to never. “Khan does a lot of work that centers around body hair, and I think her understanding and description of it is quite powerful. Body hair, when you have it mass quantity, is demonized,” Roisin pointed out.

The connotations of body hair among brown women are remarkably different than what they are for white women. “Our discomfort with the body hair, especially that of black and brown women is not just influenced by patriarchy but is also a remnant of colonialism,” Naz Riahi, the Iranian-American founder of Bitten said. “This is a system in which we were taught that fairness, lightness, whiteness and all the comes with it—blue eyes, blonde hair, less body hair—is more beautiful, appealing, better.” It is worth noting that every brown women I talked to for this story had started removing their body hair earlier in life, and at their own request.

“White women not removing body hair is quite laughable to me,” Roisin elaborated during a different conversation. “White women don’t have the history, or the baggage of growing up with visible body hair, so their announcement of it, or political positionality of it, seems insincere. Many brown folks, including me, were bullied growing up for being too hairy. When there’s no history of subjugation or even cultural abuse, it seems premature to align yourself with something that essentially has no consequence for you, irrespective of how vocal you are with it.”

The last time I went to get a wax, I found out that I’ve developed a serious allergy where my otherwise olive skin turns into a raw meat-like red, and itches insanely as soon as it comes into contact with wax. It felt like whatever allergens causing this were saying something I’ve been mustering the courage to say my whole adult life, closing the loop which began on the day of the half-waxed bikini line incident: F you, patriarchy, we are done with you in all your forms—whether you’re enabled by males or other females.

*Name of the interviewee has been changed.

Credits

Text Busra Erkara

Illustration Ayqa Khan