Flanked by her brand director and PR at her studio in Hammersmith, Fran Stringer takes a deep breath before she gives the opening quote. It’s her first interview as Womenswear Design Director for Pringle of Scotland, the oldest fashion house in the world. In fact, it’s her first interview ever, not counting her brush with the vultures backstage at her debut show in February. “It’s sometimes an overwhelming task,” she says quietly, with a girly pitch that softens her Northern vowels. “Basically every person I know has a jumper, and we pretty much invented that.” Joining Pringle is to a fashion designer what marrying into royalty is in the mortal world: everybody knows your family history better than you do, and the whole country owns a piece of you. That’s why, when fashion’s answer to the Archbishop of Canterbury, Suzy Menkes OBE of international Vogue fame, gave Stringer her gushing written blessing, the designer “absolutely cried.” Praising the collection’s feminine toughness and shapely silhouettes, Menkes simply wrote: “It is a rare compliment to make but Fran Stringer got everything just right for Pringle.”

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; text-align: justify; font: 8.5px Helvetica}

As it turns out, hiring a Northern girl to make contemporary sense of a 200-year-old Scottish heritage brand isn’t such a bad idea. Stringer grew up on the edge of the North York Moors in the seaside dwelling of Middlesbrough, at the height of the preppy 80s Pringle craze, with brothers who embraced it to the max. “They used to wear their pink argyle jumpers to go out on the town. It was a really big thing in Middlesbrough.” Her dad was an architect, her mother an early New Age naturopathy optimist, who practiced reflexology and filled the house with crystals. “She used to have a Buddhist monk come to the house on Sundays with his orange gear on, and they’d do chanting in the front room.” It sounds a tad alternative in this day and age — 20 years ago, in suburban North England, it was totally shocking. “The neighbors were like…” Stringer balloons her eyeballs. “I was a little bit fixated on it, but my dad thought it wasn’t quite right, so he used to take me to the movies on a Sunday to get me out of the house.”

Wasn’t home life quite the contrast for an architect dad? “So they’re divorced, of course,” she says deadpan, then laughs. “He got married to an accountant so it was perfect.” It’s the sensible attitude that comes with a childhood spent with inner chi and blue auras. “I’m quite Zen,” she quips. “She tells us off for using fitbits and microwaves,” says Katy Wallace, Pringle’s Director of Brand, Design and Studio. “Your mom wouldn’t let you use wifi, would she?” — “No!” Stringer exclaims, reaching a rare high decibel. She’s fundamentally composed, soft-spoken, and understatedly polished in muted, dark knitwear and fluffed-up straight jet-brown hair. Sitting in front of her look board from the show, she looks every part the woman she designs for — as has become the trend in recent years for female designers such as Phoebe Philo, Victoria Beckham, and Gaia Repossi. Stringer has a lot in common with their aesthetics: quietly luxurious anti-glamour made for a generation of women for whom embellished cocktail dresses aren’t synonymous with managing companies and picking kids up from school. (Stringer has a four-year-old daughter, Indigo, with her web developer boyfriend.)

“I’m very much a realist. I spend a lot of time thinking about clothes and how people wear them and what they mean to people and how people use them as armor or to express or hide themselves. I’m much more of a thinker and a feeler than a researcher,” she says. Designing her debut collection for Pringle, Stringer had to reacquaint herself with her instinctive handwriting, stepping into her first job as Design Director after earning a fashion degree from Nottingham Trent University in 2002 and working 13 years as part of a design team, for Topshop, then Aquascutum, then Mulberry. She expressed her newfound signature in immaculately cut knitwear, sculpturing the body in silhouettes that could best be described as arty — or clothes for the women, who like to look at it. Not that Stringer is the type of designer to obsessively immerse herself in modern art books and the weekly vernissage. “Pringle’s heritage can seem like a burden, but because of the responsibility it actually makes it a natural process. It’s not like I have to go to a gallery and find some contemporary artist to inspire me because I’ve got no ideas. All I need to do is look at the archive.”

In other words, it’s personal — and strictly realistic as opposed to escapist. “I think people have been a little bit scared to say that before because it gives connotations of being commercial, but for me that’s how I get inspired. Always has been.” In her fall/winter 16 collection, Stringer tackled that most holy of Pringle grails: the twinset, as worn by Grace Kelly and by appointment to Her Majesty the Queen. “The twin set is seen as such a prim little outfit, like 50s housewives,” she says. “But we’ve left that time behind. Women are running for president or sitting on company boards, they’re breadwinners and they’re multitasking. They don’t need twinsets anymore, so I wanted to bring a bit of attitude to it.” She interpreted knitted twindom as all-knit dressing: knit skirt with knit sweaters, knit trousers with knit cardigans, and so on. “Or this incredibly beautiful, luxurious tracksuit,” she says, pointing to a look on the board. “That’s the modern Pringle twinset.”

Stringer’s keen sense of reality doesn’t just materialize in her view of life-appropriate garments for women today, but in her astute opinions on consumerism— something she says is connected to her Northern upbringing. “Everyone works hard for their money, that’s why I’ve always had a problem with disposable fashion, because I feel like when people don’t have that much disposable income and they buy something it should be an investment. I love craft and quality and the idea of longevity. Whether that’s because I grew up in a poorer part of the country, or because people bought less back then and treasured it more I’m not sure, but that’s why I dipped into high street, didn’t like it, and moved away,” she says, referring to her time at Topshop. “I believe in less is more.” It’s a no-nonsense point of departure, which doesn’t just show in Stringer’s work but in her approach to the fashion industry, too.

How does it feel to be in the spotlight, then? “I have imposter syndrome,” she says. “Have you heard of that?” Coined by Facebook CEO Sheryl Sandberg in her book Lean In, it’s a term defined by female self-effacement. “I definitely relate to it. I’m not an insecure person and I have lots of confidence in what I do creatively, but I always think, ‘why would anyone be interested in reading about me?’ If you ask a man how he’s done at a job, he’ll say he aced it. If you ask a woman she’ll say she just happened to be at the right time at the right place. And I’m that person,” Stringer shrugs. “I think it keeps me nice and humble.”

Credits

Text Anders Christian Madsen

Photography Matteo Montanari

Styling Emilie Kareh

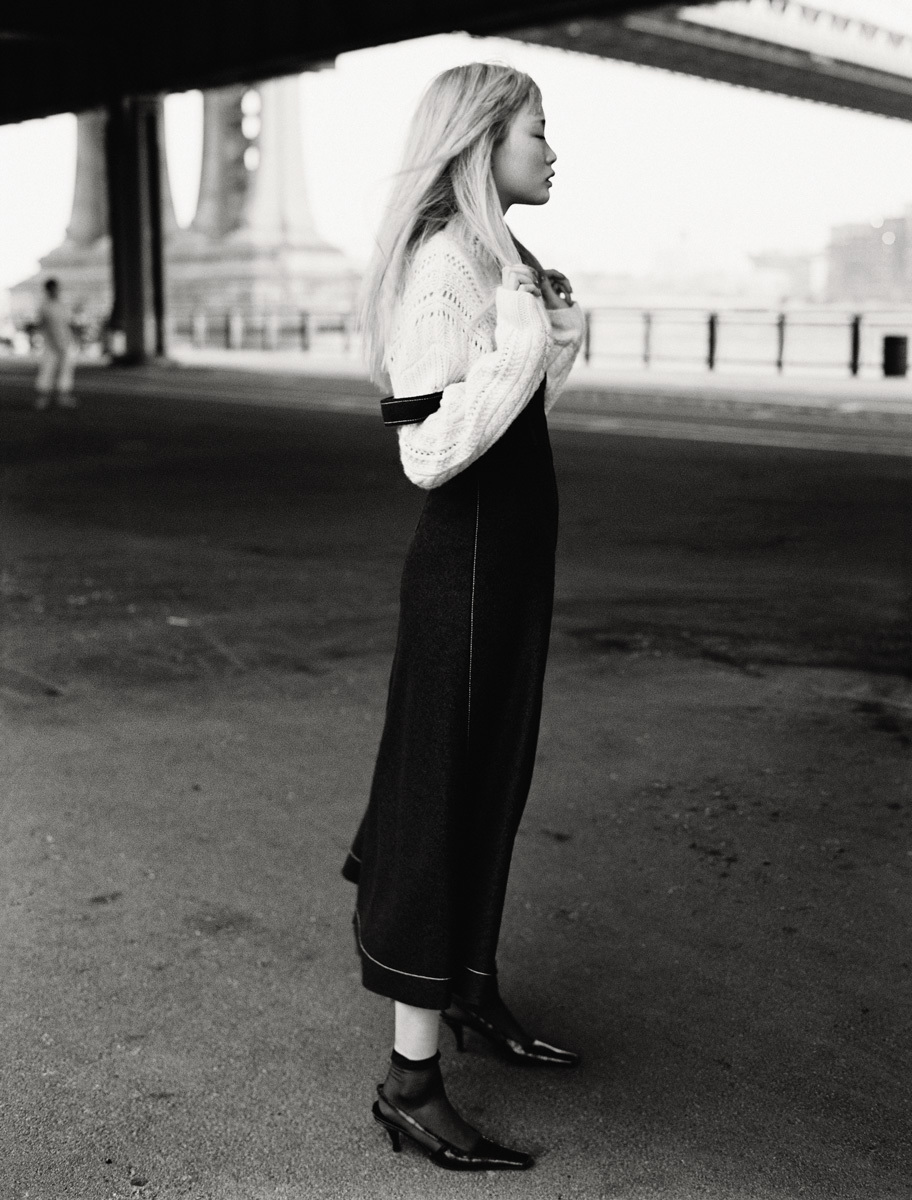

Hair Franco Gobbi at Streeters using Bumble and bumble. Make-up Fara Homidi at Frank Reps using Chanel Le Rouge Collection No.1 and Le Lift V Flash. Nail technician Donna D at ABTP using Chanel Le Vernis. Photography assistance Nicola De Cecchi, Leonardo Ventura, Joseph Trisolini. Digital technician Diego Serralta. Styling assistance Shant Alvandyan. Hair assistance Monet Moon. Production manager Richard Cordero for Select Services. Production Select Services. Model Fernanda Ly at Viva London.

All clothing (worn throughout) Pringle of Scotland