Football, for all the reductive and easy-write headlines of violence and hooliganism, is just as much about bringing people together as it is about division. For every moment of tribal hostility, there’s a moment of cross-cultural solidarity. Because at its best, football is about community and belonging and togetherness, and not just a game on a pitch or warring fans off it. This dichotomy is revealed in its clearest each time the World Cup rolls around, and which usually has an uncanny way of mirroring global politics, no more so than this year’s event, in Russia. So you start with horror stories about the locals and the travelling fans, the racism and homophobia and the Novichok nerve agent and rival dictatorial political dick-swinging. But almost always we end up with something more nuanced and human and interesting.

So the World Cup shines a light on football in its broadest and most social sense. London never feels more harmoniously multicultural — from Nigerians to Colombians, the Poles to the Portuguese — than when a World Cup starts. It focuses the attention on football closer to home, on a smaller, more intimate scale. Football as something positive and uplifting.

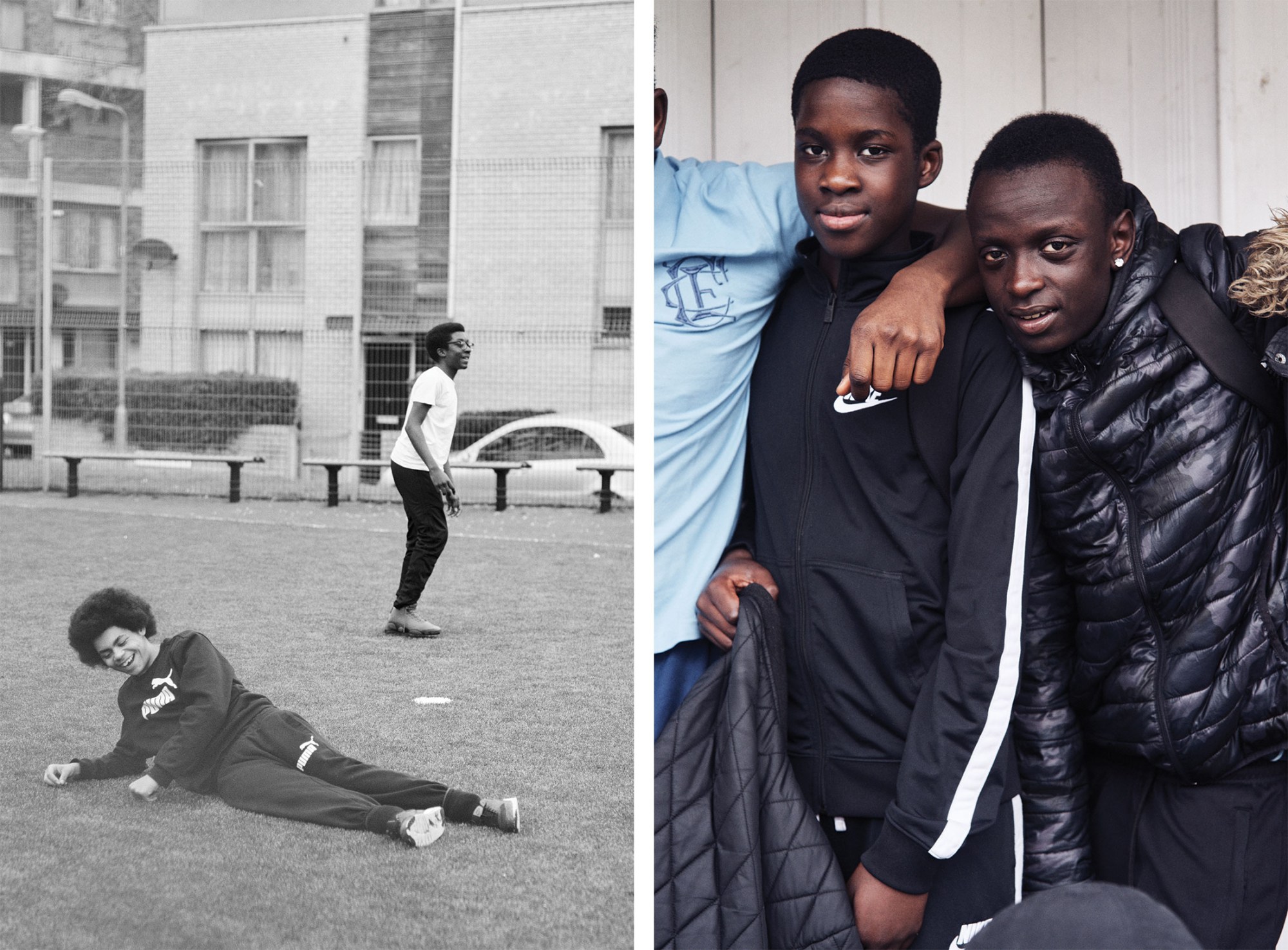

Which brings us to Football Beyond Borders, an educational football charity working across London, using the power of football to help and educate and support young people in the capital. It was started by Jasper Kain in 2012, but has taken a circuitous route to its place today. They started working with 12 boys in Croydon and 25 in Camberwell, and now provide to support to over 400 children in 11 different London boroughs, running 24 projects across the city, and working with Nike on a project that celebrates the diversity of the players.

The story begins with Jasper, who was, for a time, a youth team player at both Chelsea and Gillingham. Training at Chelsea, and travelling back and forth to London he ended up meeting a whole different world of people to those in the rural area of Kent he grew up in. “After I was released from Gillingham at 16,” Jasper begins, as we sit down on a sweltering hot day on the eve of the World Cup, “I just associated football with failure.” Heartbroken he drifted away from the game, until university when he started playing again, and began to see football in a new light. To see it as something positive, “an enabler for our own self-development, to give us more confidence, or a bit of discipline, and it was a way of bringing people together”.

The first iteration of Football Beyond Borders involved Jasper and some friends, who would travel around the world playing football among divided communities. It took them from Palestine to Syria, from the Balkans to West Africa. They remain, even today, the only British team to have played in Syria. And then, the London Riots of 2011 happened. “I felt compelled to do something,” Jasper says. “I got the sense that a lot of the young people in London were very angry and didn’t have a way to express it. I ended up volunteering on a Friday evening at a youth centre in Camberwell; I just used to go down there and quickly realised that young people need to develop trust in order to build a relationship, and need a way of communicating, and the easiest way I knew to do that was through playing football.”

So Jasper started running ad hoc drop-in sessions at an estate in Camberwell with the friends who he’d been touring with. “For a couple of years we used to do it when we could,” Jasper recalls. “We used to run a thing on a Wednesday evening in Kennington Park and boys would come from Brixton, Peckham, Walworth Road… They’d come together, and we had a really simple philosophy; no swearing, no weapons, no bikes on the astroturf. We ended up doing a project at a school, and that’s when everything changed, that was about 2014. We registered as a charity and the rest is history.”

FBB focusses its work on kids transitioning into adolescence, helping them navigate that difficult time in their lives when there isn’t a lot of support. A lot of their work circles around simple things like engaging them in schools, preventing exclusion, helping kids take pride in their work, teaching them skills. It’s about including them, making them feel valued, respected, understood. It’s emotional, as well as practical. It’s centred around football, but it’s deeper than that. Football is just the way in. They work intensively, seeing the same people every week of every year.

FBB is a beacon of hope in an era of austerity-enforced cuts that cancels many programmes. But, as with anything like this, in an ideal world an organisation like Football Beyond Borders would not need to exist, and instead everyone would receive the same opportunities. “There’s been huge cuts to youth services and the charity sector has been expected to pick up the slack on the cheap,” Jasper states. “And it’s the most vulnerable young people who need that support. If you increase class sizes, take away teaching assistants and support workers, if you take away interventions like ours… Young people crave validation, recognition and support. They’ll go and find it somewhere else if you don’t offer it to them, and where that may take them is quite troubling.

“There’s a difference between school and education, and education is a lot bigger and broader, and shouldn’t just happen in the school. Football Beyond Borders is about education, and the difficult thing with all of this is that without the consistency of funds, it’s hard to plan. That’s easily the biggest challenge.”

Part of FBB’s educational work this World Cup has seen them link up with Nike for a project celebrating the diversity of London. “A lot of the kids we work with have these very multicultural identities,” Jasper begins. “And we wanted to celebrate that.” So they’ve come up with A City of Nations, a tribute to the diversity, inclusion and cohesion experienced by young Londoners during the World Cup. “We’re looking at six nations in London: England, Brazil, France, Portugal, Nigeria and Poland. So the young people have gone out, researched the different nationalities. They’ve got to produce a photo exhibition and magazine and they have to organise the exhibition with us at Niketown. And we connected the young kids with Nike to do their England kit launch. That, in and of itself, doesn’t necessarily mean anything, or help, but for these kids to see themselves, for their parents to see them, in Oxford Street. It’s a big deal. That recognition.

“Ultimately, for young people there’s a big vacuum in a lot of communities. Young people want positive reinforcement within a safe environment. To explore and make mistakes, and you have to create those environments. Unfortunately what’s happened in our community is these vacuums are created with a lack of youth provision and lack of role models. Role models for young people aren’t just Harry Kane or Raheem Sterling. They’re also just a mentor who’s maybe five years older than them. When there’s potentially one option that’s not necessarily a long-term, positive, sustainable option — becoming a Premier League footballer — they need a viable alternative.”

Help support the incredible work that Football Beyond Borders do by donating here.

Credits

Photography Edd Horder