When protests broke out following the shooting of Mike Brown in 2014, America’s attention turned to Missouri and the burgeoning Black Lives Matter movement. But for kids like Daje Shelton, the charismatic star of Jeremy S. Levine and Landon Van Soest’s new documentary For Ahkeem, Brown’s murder was nothing out of the ordinary. Recalling their first meeting with Daje, Soest remembers the teenager only being surprised that Al Sharpton was coming to town. That initial meeting actually made it into the documentary: Daje crashes an early filming session at a friend’s sleepover, flops down on the bed without even looking at the camera, and effectively shapes the whole direction of the film.

Levine and Soest started filming For Ahkeem before photos of the National Guard squaring off against Ferguson protesters went viral on Twitter. The uncompromising coming-of-age story follows Daje for more than two years, the protests providing the backdrop for other experiences commonplace for black teens in America: being thrust into a court-supervised alternative high school, getting pregnant, and navigating her own adolescence while preparing to raise a black boy in a place where black boys are often killed before the age she is now. For Ahkeem is not a particularly hopeful film, but the charismatic teen at its center prevents it from being too depressing. Even as it premieres during another pivotal moment in modern American history: the presidency of Donald Trump. It’s difficult to see things improving for kids like Daje in a public education system now controlled by Betsy DeVos.

As For Ahkeem premieres at Tribeca Film Festival, we talk to the directors about the school-to-prison pipeline and what Daje can teach us about ourselves.

How did you become interested in Missouri and the school-to-prison pipeline as filmmakers?

Landon: We started researching this idea of the school-to-prison pipeline and these really harsh disciplinary policies that were taking kids out of school and funneling them into the prison system. Through a producer contact we met a judge in St Louis who was really pushing back on that and saying, “I’m not going to perpetuate these cycles. I’m not going to continue to send children to prison after I’ve imprisoned their parents.” He created this space that sounded really incredible, and was really generous in giving us full access to the school and to the courts. As documentary filmmakers, it was an amazing invitation to get to see this first-hand.

Jeremy: We started filming about a year before Ferguson broke out. So it wasn’t that specific event that brought us out there, obviously, but it was more just a sense that there was this place in the middle of the country where a lot of these issues were coming to a head. There was so much tension in the community. It’s not so unlike a lot of other cities in the United States where there is this stark dividing line between black and white, between the wealthy and the poor. But in St Louis it’s even more stark of a line. There’s this one street called Delmar Boulevard that really splits the north and the south. There was this sense that there was definitely a story there. More specifically, we had heard about this school that was set up by a judge that was a way to prevent or stem the school-to-prison pipeline. It seemed like a really interesting model.

How did you meet Daje and why did she want her story to be told?

Landon: From the outset, we really wanted to look at it from the students’ point of views. We probably did interviews with 30 or 40 students, but then this girl Daje literally walked into the frame and stole the show. We knew from the outset, being obvious outsiders — a couple of white guys coming in from New York — that we really needed a partner who was going to open up that world. She was so obviously that from the beginning. Literally the first time we talked to her officially, she leaned across and got down on her elbows and was like, “You want to know what’s really going on? Well this guy’s got beef with that guy…” She broke down this whole fight that was going on and started telling us about her mom and her dad. She had such a burning desire for expression.

We were filming with her in this standard verite style for quite a while, but as we go to be a lot more friendly, we’d be driving around in the car and she’d be like, “I have to tell you something.” It would be things that would make your jaw drop. I remember asking her if she had a journal where she ever wrote things down, and she was like, “Yeah, I write every day.” She ultimately started opening those journals up to us and we started building off her entries for the narration.

Jeremy: For a lot of teenagers, you might just be really caught in the moment, and things just stay at that present level. For Daje, it was always clear that she had this incredible ability to step back and look at the situation that she was in, and all the different factors that were feeding into it.

That initial scene with Daje and her friends braiding hair on the bed is so remarkable. It has tropes of an innocent teen girl movie but she has a bullet wound and is talking about her cousin being shot.

Jeremy: The way she told that story was not so dramatic. What was shocking to us was how commonplace it was. Talking about the cute boys, and talking about getting shot. For me, in my childhood, I didn’t know anyone who had been shot. That contrast was shocking and startling. It says so much about the disparities that exist in our society.

Landon: I think the normalcy of that scene was part of the reason it was so important for us to keep in the film. It sort of foreshadowed everything that happened with Mike Brown. It was such a surreal experience for us to be there and see national news popping up everywhere with this story, and here we are just a couple of miles away in the school. Discovering it with those kids and seeing the way that they reacted to it was so eye-opening, that it was so commonplace. What they were so surprised by was the fact that it was getting attention, not the fact that it happened. The fact that she was so quickly to pull up her cousin and be like, “That just happened to my cousin last year, he got shot 25 times.”

The Ferguson uprising begins after you’ve already started filming. Was there much discussion of how you were going to approach those events in the documentary?

Jeremy: It was clear that something was happening that was shifting our national conversation, and it was happening right next door to the film we had been making for a year. We knew it was an important part of what we had been looking at for a year. I think there is a temptation to say, “This is interesting, let’s go film there.” But for us it was important to tell it through Daje’s eyes. In the film, she’s pregnant at the time, with a boy. Her immediate thoughts upon hearing this news were what it would mean for her son, growing up as a black boy in St. Louis. What would happen when he grew up and would be perceived as a threat just because of the color of his skin?

Landon: There is that temptation when there’s so much attention around Ferguson. We were literally there before any other media, and we could have shot far more footage than we used in the film. We were there for a lot of these historic events. At the end of the day, we grappled a bit with what our role was in exploring that, and we were so invested in telling Daje’s story that it was more interesting for us to look at the way that she was internalizing those events and the impact that they had on her personally. That’s still not being talked about enough — what it means to be a young black person in that community. It’s easy for mainstream press to descend on these events and portray them as isolated and contained, but the fact that this is an ongoing reality for so many young people is something that we really hope the film can get people to start talking about.

For Ahkeem is not strictly pessimistic or positive. There’s that one classroom scene with the poster of Obama on the wall, which seems to signal hope, but it later comes down when Daje is not doing so well.

Jeremy: We really wanted to resist the temptation to make the type of documentary that has become a bit of a cliché in a lot of ways. We wanted to tell a true story of this girl, Daje, and have it resonate in a way that would feel true to her and true to the situation. We didn’t want to provide false hope. The school does incredible work for what it can do. But ultimately there are much larger issues. There are these harsh disciplinary policies that suspend black and brown kids from public schools in such a high number. It’s incredible that Daje does triumph in big ways, but that doesn’t mean that her life is going to be easy from this point forward.

Landon: It’s a challenge with art that is trying to have some sort of social commentary. Especially in storytelling, there’s a tendency to have the big finish with a big triumph and success at the end. At first we were so invested in whether she was going to graduate and whether the program was going to help her, but the deeper we got into it, we realized that whether she does or not, she still has such tremendous challenges personally in the future, as do so many other kids like her. It’s something that is so deeply rooted in our society and we need to continue to chip away at it and explore it rather than pretend it’s all solved by one program or one teacher or one principal.

The film is premiering during another crucial period in America’s history, the election of Donald Trump and appointment of people like Betsy DeVos. How difficult is it not to feel more cynical now about the future of kids like Daje?

Jeremy: The good news is that there are so many people involved in trying to fight back. Disciplinary policies and police policies can be part of that struggle. But it’s certainly hard. Things certainly weren’t perfect under Obama. Daje and her communities were left behind in a lot of ways. But with the election of Trump, it’s going to get that much worse. We know that Daje and her family are going to be among the communities most affected by these policies.

Landon: It is terrifying to see our educational and judicial policies going backwards. It’s scary on every front. But it makes the work that we’re dedicated to all the more important. We need to continue to tell stories like this and to have these conversations. During the Obama years, it was possible for a lot of liberal white America to think, “Oh, we’ve solved these problems.” The election of Donald Trump is an obvious indicator that that is not true. Racial sentiments and the problems that are at the root of what we are exploring in the film are still extremely present in our country.

At least a large part of America is waking up to the sort of race and class divisions that Daje’s community was already acutely aware of.

Landon: There’s a lot more outrage around here. We’re sitting in this very liberal bastion of Brooklyn and we want to believe that the world is a certain way. For people in Daje’s community, it’s not a surprise that there’s a lot of very overt racism. They’ve dealt with generations and generations of racist white presidents. It’s not such a big shock to them as maybe it is to us. Going back to the progress that we want to believe it’s made. There’s an incredible awareness of politics and these issues that maybe we weren’t talking about before.

Jeremy: It’s worth pointing out, too, that it was the people in Ferguson and the surrounding areas who made these issues come to national attention. That they went to the streets day in and day out and made people pay attention is really inspiring, and probably helped lay the groundwork for what’s happening around the election of Trump. At the very least, it’s now more visible. It’s not that there’s more racism, but that it’s out in the open. We can acknowledge it, and if we can acknowledge it, maybe we can finally do something about it.

Credits

Text Hannah Ongley

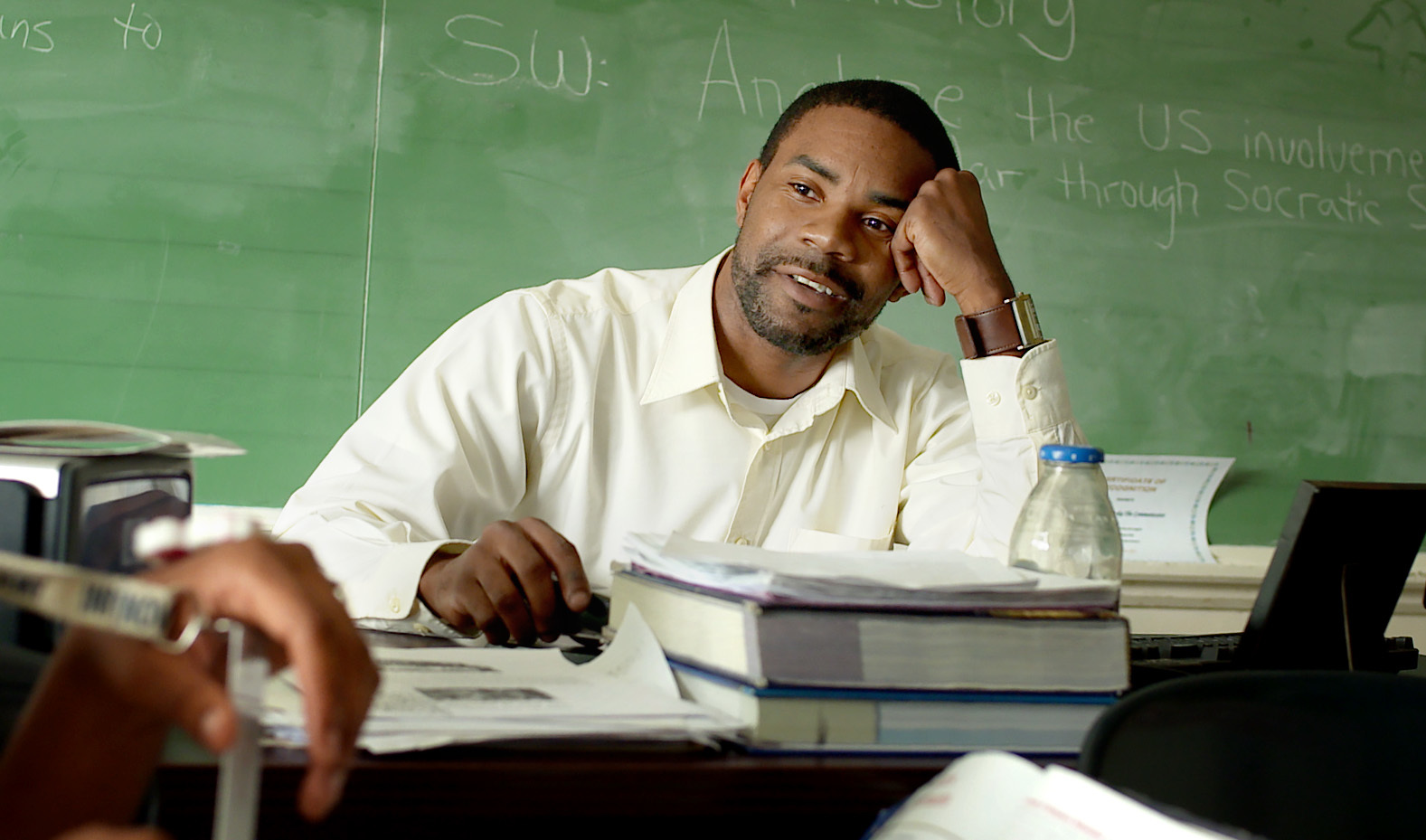

Stills from For Ahkeem