The play For Black Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When The Hue Gets Too Heavy is shaped by safety. This much is true to the actors who star in it: “This show literally saved my life,” says Emmanuel Akwafo, who plays Pitch, “because I’ve never been able to perform a character where I give so much out that it heals me on the daily. If I’m feeling frustrated that day or if I think of something that triggers me, there’s moments in the show where I can literally release it and be free and know that I’m safe with my brotherhood.” Such catharsis extends to the audience of For Black Boys… as well, in its expression of both the constant pressures, large and small, of anti-Blackness, as well as more specific discourses surrounding Black identity — and what that even means to its multifaceted characters.

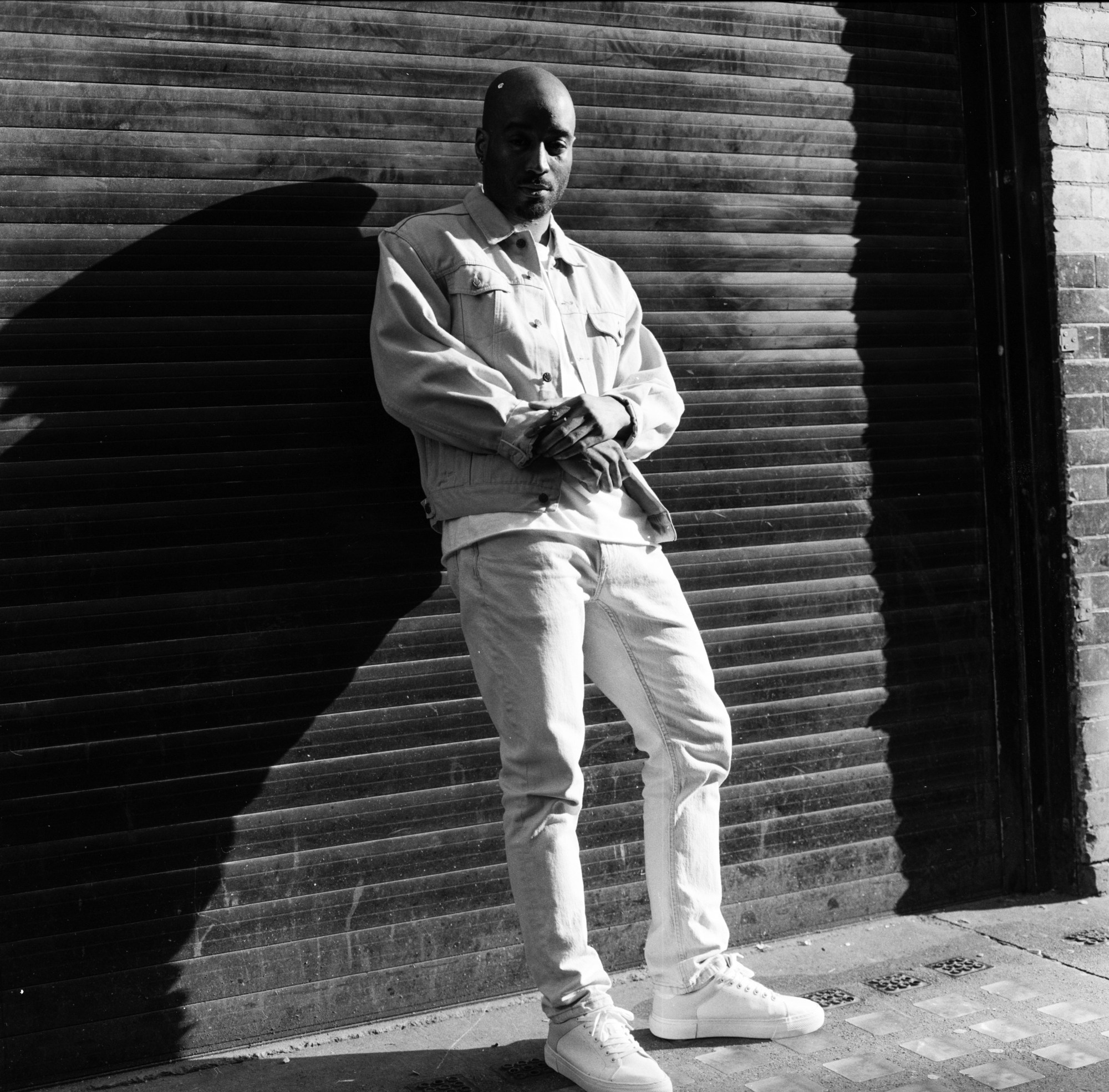

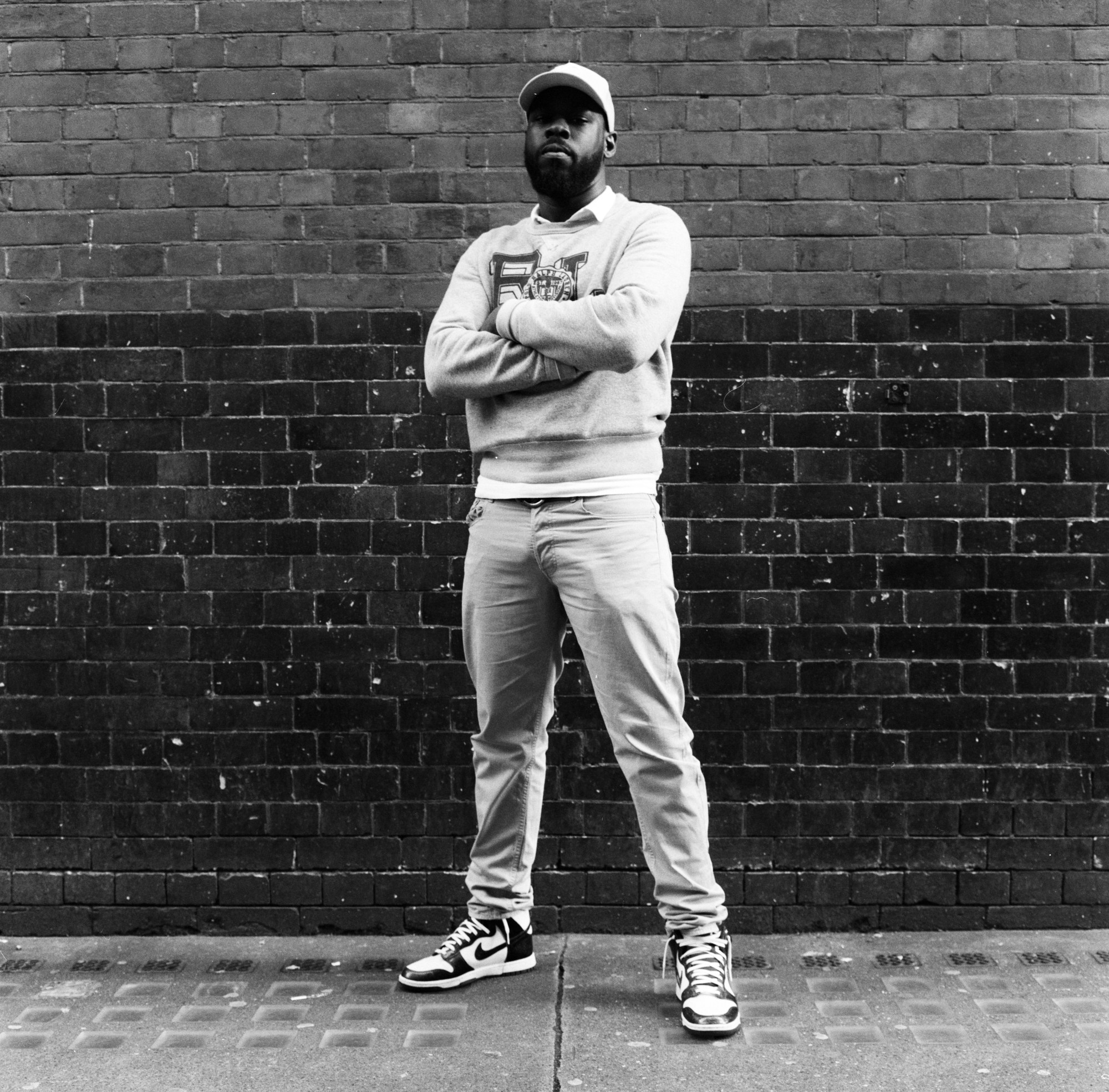

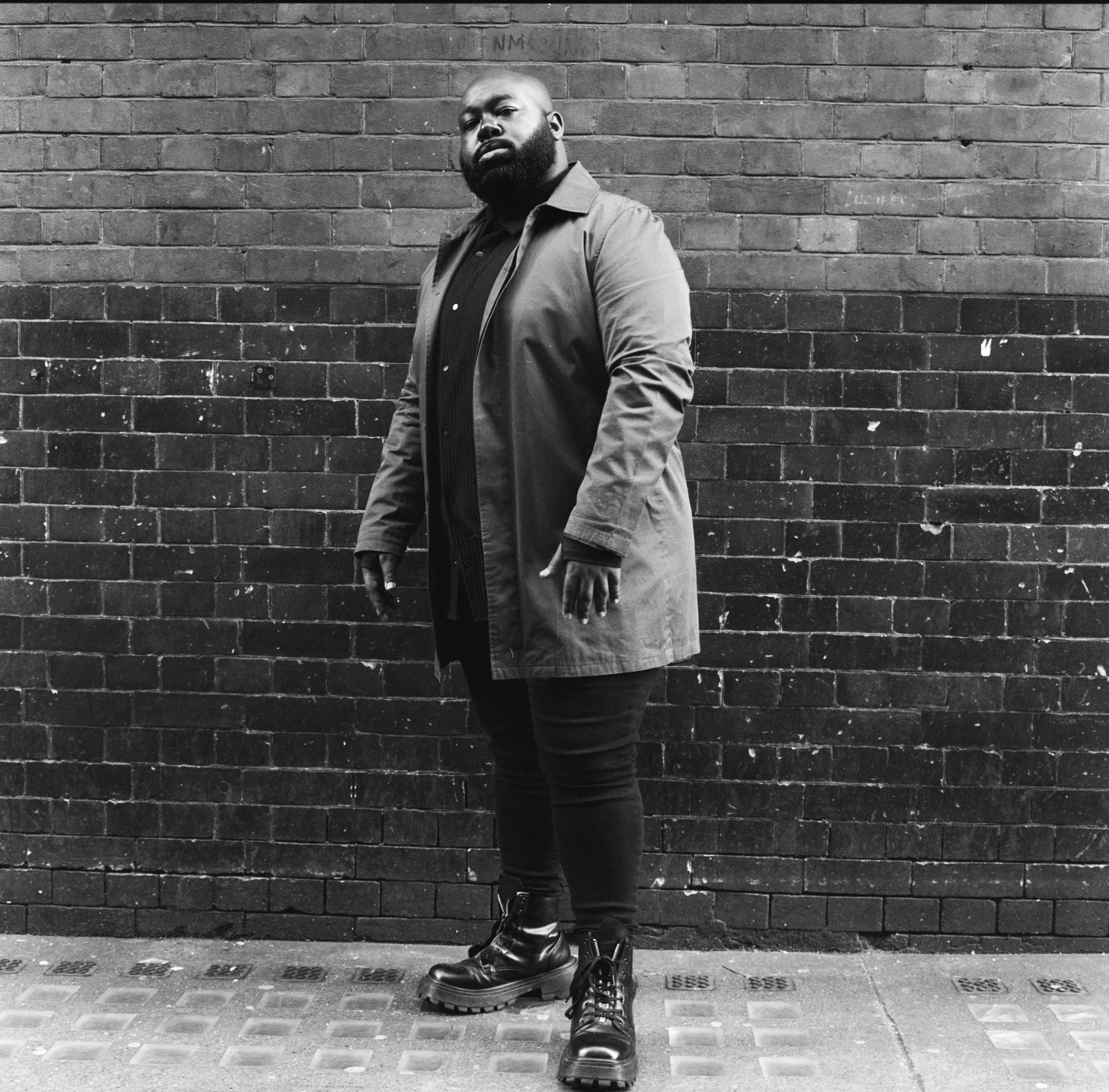

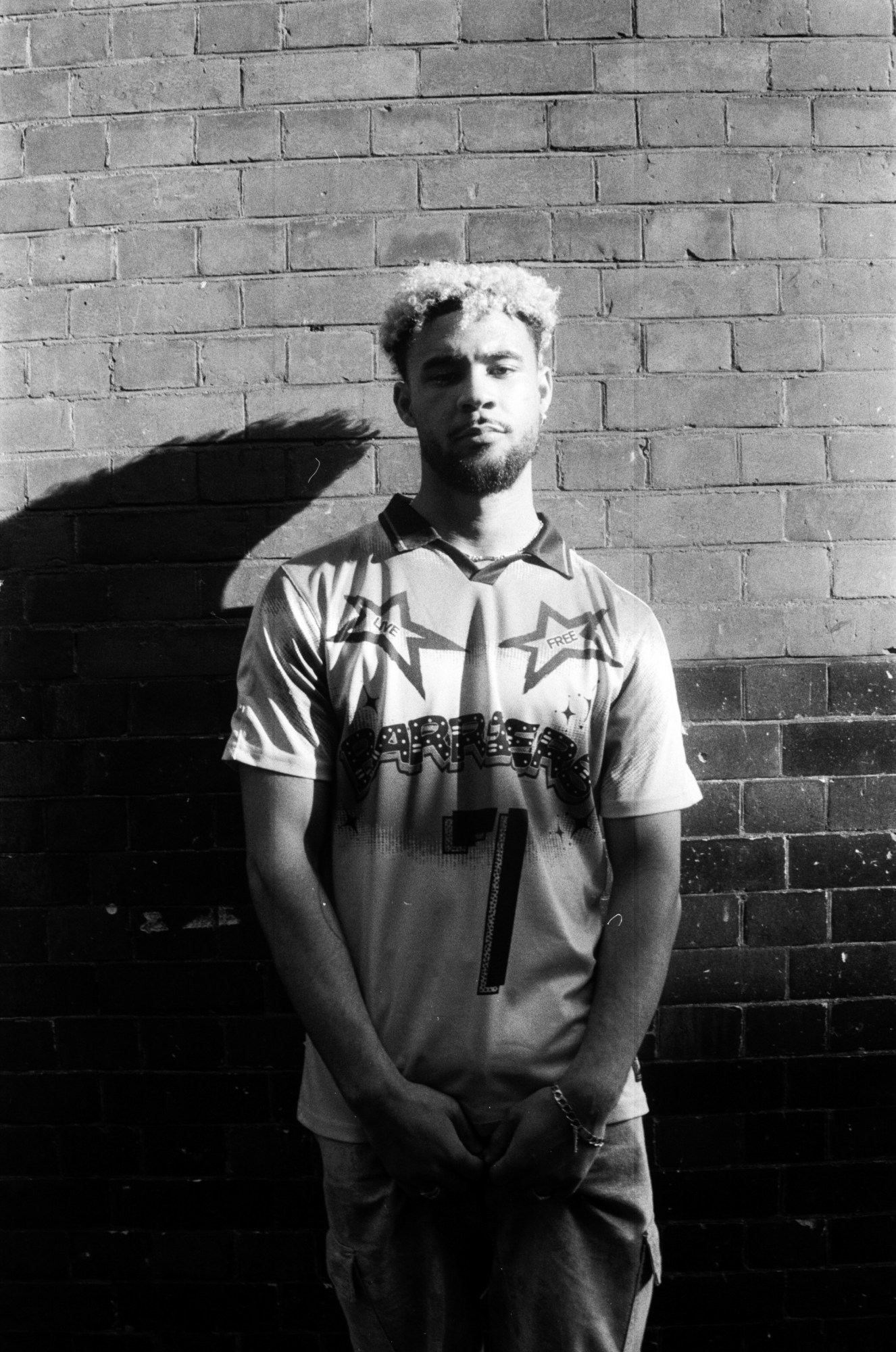

The sensitivity of writer and director Ryan Calais Cameron (as well as original director Tristan Fynn-Aiduenu, who helmed the show during its first run at the New Diorama Theatre) feels miraculous. It ambitiously seeks to portray a spectrum of experiences, running counter to the frequent codification by others of Blackness as something monolithic. The show all comes back to the simple idea that Black identity is not inflexible or uniform, unspooling into a poetic work about Black lives and questions about what we’re taught about them (like the complexities of African diasporic history being reduced to the slave trade — important, but not the only thing of significance). There’s no single shade of person — and so the characters are named after different shades of the colour black: Onyx, Pitch, Jet, Sable, Obsidian and Midnight.

Taking direct inspiration from Ntozake Shange’s 1976 choreopoem, for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf, Ryan says he began writing the play in the wake of Trayvon Martin’s shooting in 2013. Adapting Ntozake Shange’s work to discuss similar themes along the margins of Black masculinity, it feels distinct for its mix of tones and styles of storytelling. As one star Aruna Jalloh, playing Obsidian, puts it: “[For Black Boys] has got a lot of music and dance in it, but it’s not a musical. It incorporates all of that in a way that is truthful to our culture, the things that we recognise, in order to help tell a very deep story. One that’s very honest and very raw.”

Following sold out runs at the Royal Court Theatre and the New Diorama Theatre, and currently playing a six-week run at the Apollo Theatre in London’s West End, For Black Boys… is striking for all audiences. For myself, it was uncanny seeing anxieties I’ve felt growing up in Britain addressed and debated with gorgeous expressiveness, as well as sometimes uncomfortable candour. Its stars highlight how personal it is for Black men everywhere. “You come and watch this and two hours later it’s over, but for many Black boys, this play continues in their hearts and in their minds,” Nnabiko Ejimofor, who plays Jet, says. “People say to me, ‘Is it hard doing this play?’. I’m like, ‘I’ve been doing this play for 27 years. That’s been my life’.”

All of the men play somewhat archetypal characters who gradually reveal their true selves and anxieties, as it becomes clearer that they can be vulnerable around each other. Onyx, played by Mark Akintimehin, and Aruna’s Obsidian both wrestle with how their appearances lead others to predetermine how they should behave. Nnabiko, playing Jet, struggles with his queer identity. As Pitch and Sable, Emmanuel and Darragh Hand lead the play’s treatises on loneliness and self-image. To Emmanuel, the variance in body type is key: “For me, it was the first time that I’ve seen different shapes and sizes of Black men being free and unapologetic.”

As For Black Boys… progresses, a constantly evolving group therapy session transforms into something more intimate. Its sparse stage set up, beginning with just six chairs and a backdrop of block colours, leaves room for more physicality. As well as performing their own characters, the cast slip into supporting roles in each other’s flashbacks. As Aruna describes it, it was simply a part of their preparation: “In the first week at New Diorama, we would all double up and would play different characters in each other’s stories”, and that the switching of characters in these exercises worked their way into the performance. Tristan’s direction acted as the ground the play was built on. “I don’t think this play would be what it was without the foundations that he laid,” Darragh says. “He created such a beautiful culture amongst us.”

Safety and mindfulness were essential to that foundation. “They made sure we had a decompression room to make sure that if something was challenging, we could calm down,” Kaine says. “We also had a drama therapist to make sure our mind was right.” He recalls advice Letitia Wright gave the group: “[Your wellbeing] is like drinking water. You need to stay hydrated’,” he recalls. “We make sure to fill up on joy, happiness and love.”

Perhaps the most surprising and joyous aspect of For Black Boys… is its bursts of music and choreography, itself containing a variety of styles — krump being invaluable here — that might overlap with another in any one moment; serenades turn into upbeat dance numbers and vice versa. Kaine acted as song captain and Nnabiko as dance captain — “keeping us sharp” as Mark puts it. A sudden Magic Mike-esque turn in the opening of the play’s second half comes courtesy of movement director Theophilus O. Bailey, himself a resident cast member of Magic Mike Live as well as the latest film, Magic Mike’s Last Dance.

“With Black boys especially, their physicality can be seen as aggressive or something like a caution,” Nnabiko says, “something that’s not vulnerable, something that’s not sensitive, something that’s not loving”. White instigators of violence against Black boys will cite an intimidating frame or appearance as a justification for said violence; take the murder of Trayvon Martin. For Black Boys… takes that physicality and shows the truth, its potential for expression and beauty. But it’s not all just softness. Of course, there is anger too. As Nnabiko says: “Why am I denied anger? Why am I denied this emotion? And it’s something that we as Black people should be allowed to feel, and when we feel it, not be judged.”

The musical non-sequiturs and the comedy of For Black Boys… are not a frivolous distraction, it alleviates the show’s more upsetting material and demonstrates the breadth of what should be embraced more often in storytelling around Black lives. It’s all part of one of the play’s most straightforward messages: the Black experience isn’t monolithic, so why should expressions of that experience be?

In that same spirit, it elegantly threads comedy throughout even its more serious subject matter without becoming insensitive — some friendly roasting here, some ironic observations and gallows humour there — never reducing the emotional significance of what a character is admitting, while also trying to be honest about how people try to cope and comfort each other. Sometimes the fourth wall breaks; at one point, the men throw out pick-up lines to members of the audience. The cast explodes into a joyful argument over who was leading with the most cheers: “If you flop your chat-up line, it’s long for you. We’re going to clown you on stage,” Darragh says.

The cast’s hopes for the impact on its audience are straightforward: they hope it begins a conversation. “We don’t expect everybody to run straight to their houses and go and hug and kiss all their family members, but just planting the seed can be enough”, Mark says. “Planting the seed that these things are possible, this is what they look like. You want to act to the point where you’re not acting, and that’s how this is, because it is very real. So we want to keep it as authentic as possible, just so that people can see themselves in it, and hopefully extend the healing into their own lives.” For Emmanuel, the play represented self-love, while also illuminating a path forward career-wise. “It’s made me realise that I want to do work that speaks, that has truth and that can heal people”, he says. For Kaine, it’s more of a hopeful, anti-assimilationist message, hoping that For Black Boys…, in its own way, might allow people to realise that “they can be themselves, man. They don’t have to change. Your identity is your identity.”

For Darragh, the show represented a starting point for more candid and vulnerable discussions. He invited his dad and his brother one night. “I had conversations with them afterwards that I wouldn’t have ever thought in a million years I would’ve had with them. This play freed up space for that conversation to happen.

“If that could happen for everyone,” he says, “that would be lit.”

‘For Black Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When the Hue Gets Too Heavy’ runs at the Apollo Theatre until 7 May

Credits

Photography Milo Matthew