Carvell wears jacket and trousers Fendi. Briefs Sunspel.

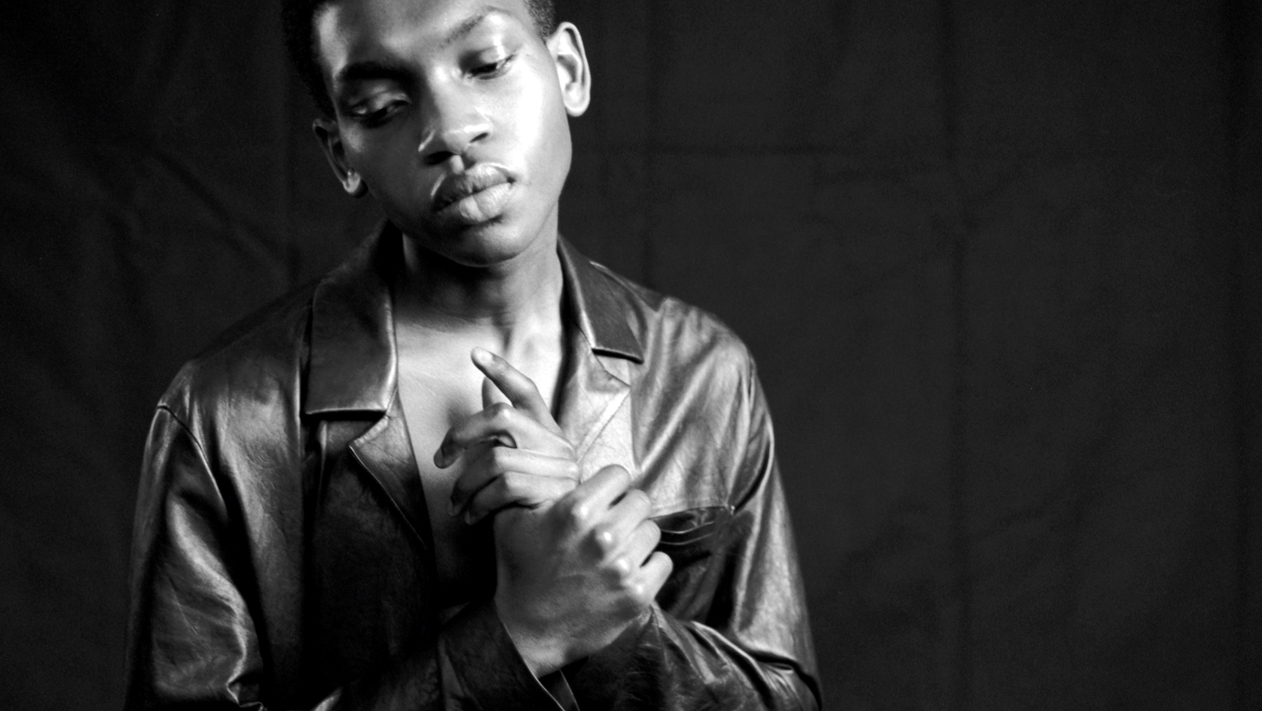

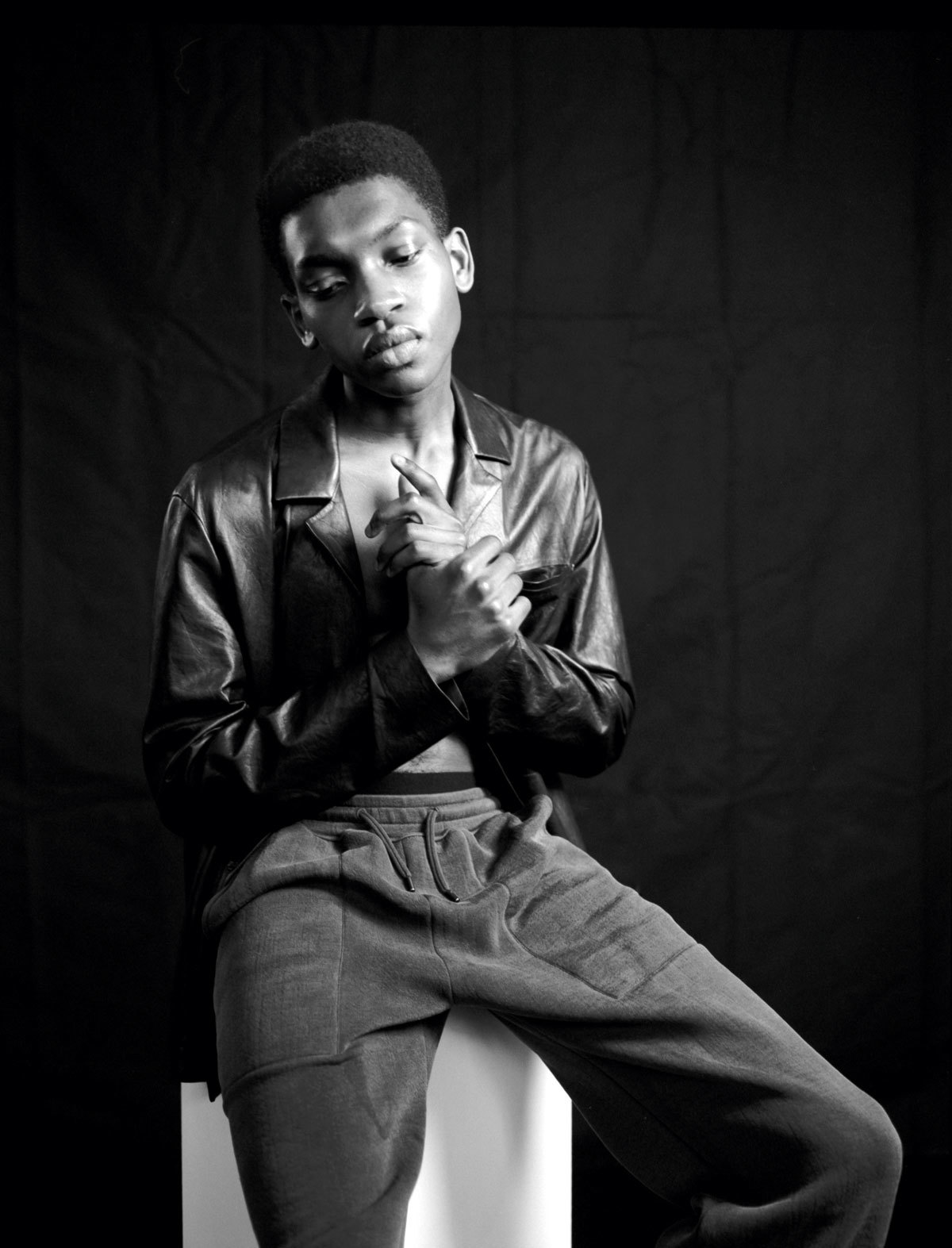

Terry wears jumper and trousers Fendi. All jewellery model’s own.

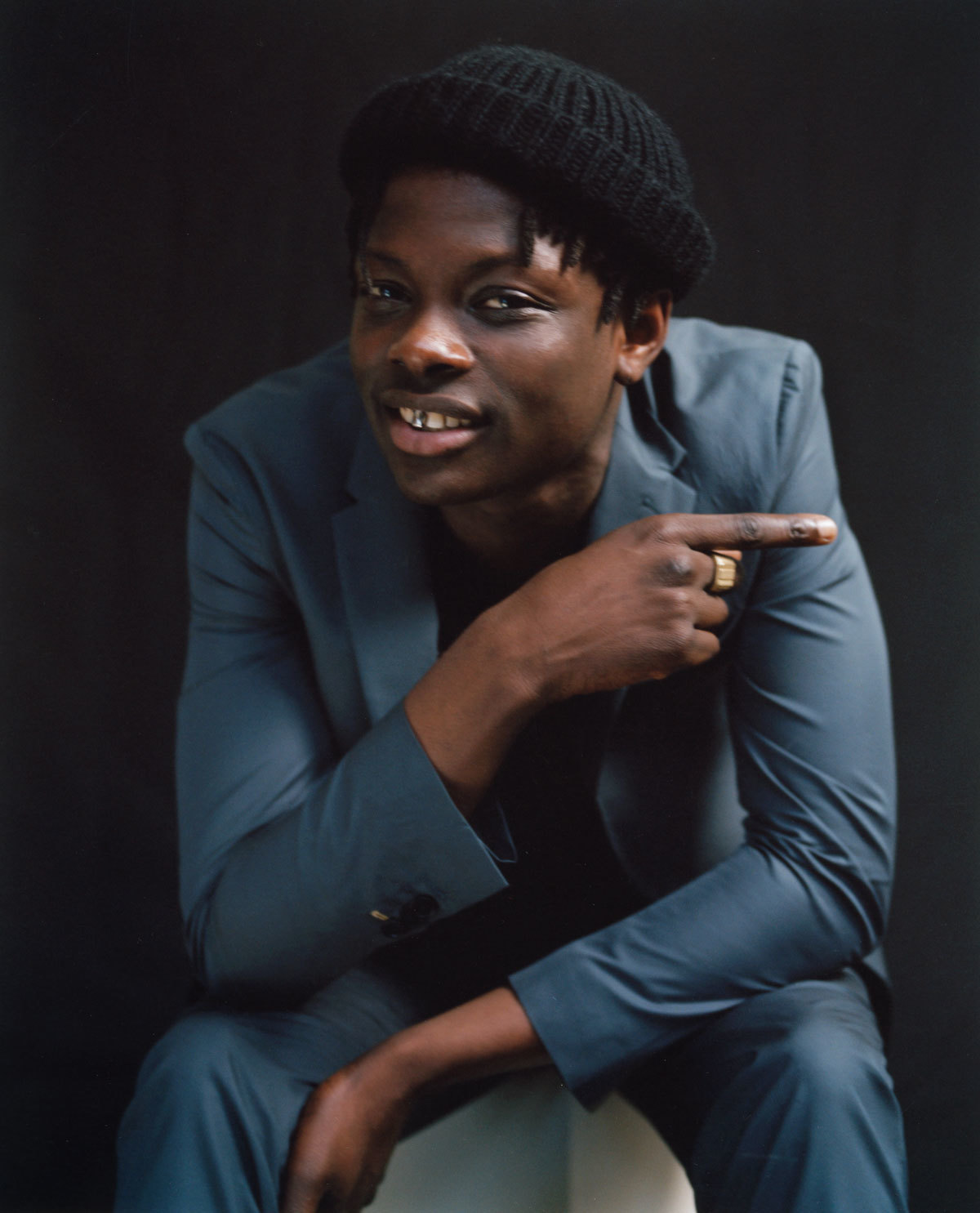

King wears suit Fendi. Ring and hat model’s own.

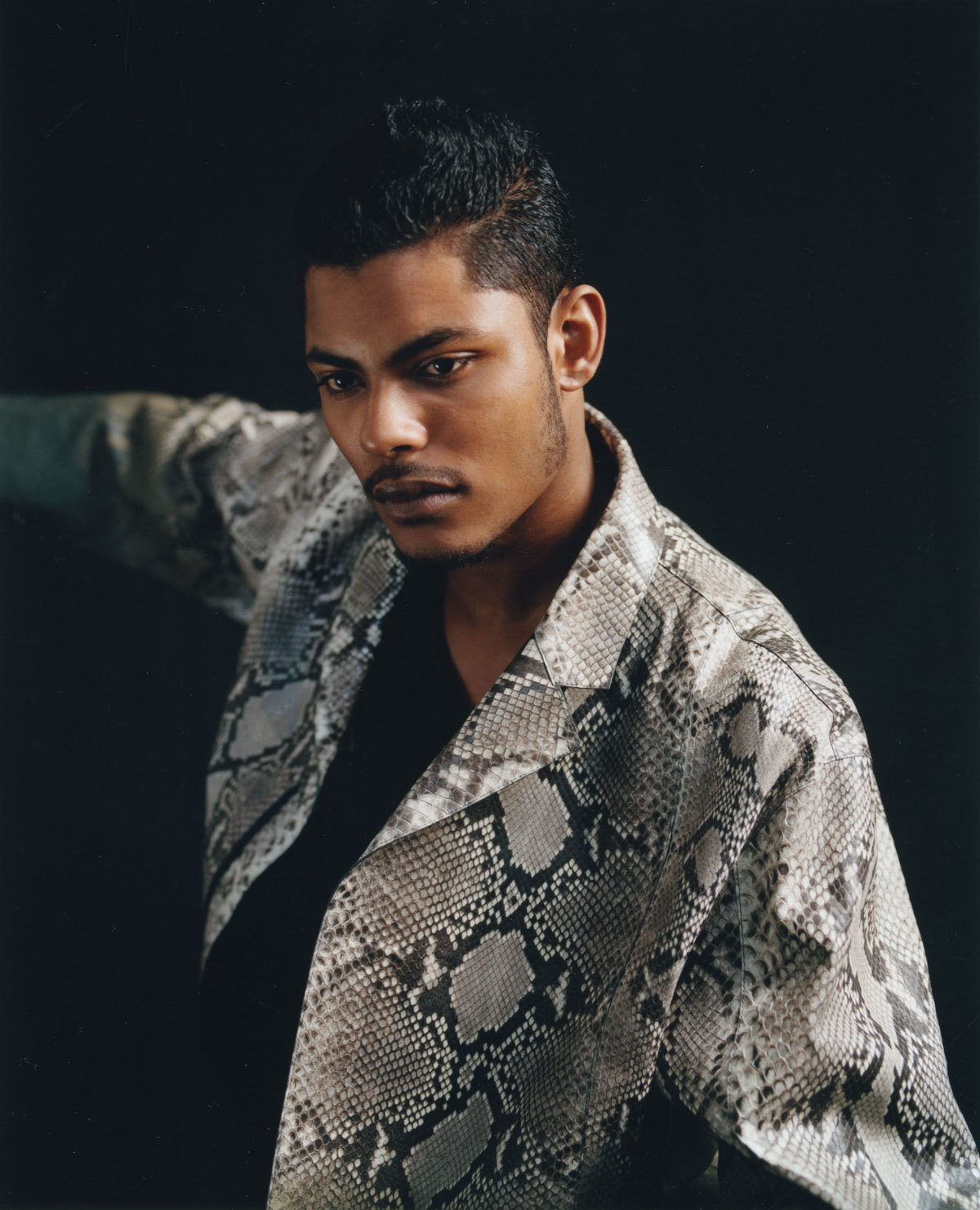

Kyle wears jacket Fendi. T-shirt model’s own.

Carvell wears top and trousers Fendi. Mahad wears top Fendi. Jeans model’s own.

King wears suit Fendi. Hat model’s own.

If you need any further proof that Italian fashion is back in control, pay a visit to Silvia Venturini Fendi in Rome. From her penthouse office in the imposing Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana, the matriarch sits atop her dynasty’s six-floor seat of power overlooking her imperial hometown. “Sometimes I have to wear sunglasses in here because the light is so strong,” she says casually from behind her massive desk, not realizing what a fabulous statement that is. Built by Mussolini in 1943, the masterpiece of monumental architecture towered over Rome as a ghostly shrine to his fascist reign for more than half a century before Fendi — powered by its owner LVMH — decided to move in and give it new meaning. After years of renovations, last year the old fur house could finally let new light in through the Roman loggias of the ‘Square Colosseum,’ and with miraculous timing. The building now stands as a tribute to a new era in Italian fashion where the old houses of Rome and Florence are reinventing themselves on their Milanese — and in Valentino’s case, Parisian — runways. Alessandro Michele has started a revolution at Gucci, Peter Dundas is revamping Roberto Cavalli, Massimo Giorgetti is shaking up Emilio Pucci, and at Fendi, well, an actual Fendi is giving her rival houses a run for their money with her new vision for menswear.

If it sounds like the Medicis, Sforzas and Borgias are back at it, Silvia — as she is casually known in the company — says the battles of Italian dynasties 500 years on is of a friendlier nature. “There’s a competition but we’re all good friends. Fendi and Gucci, for instance, there’s always been a competition. When we were children I was very good friends with the Gucci boys. We lived next door to each other. One night I went out with Guccio Gucci on his moto, and it was the time of kidnappings,” she recalls, referring to the great-grandson of the founder Guccio Gucci Sr. “He said, ‘Can you imagine if they kidnapped both of us now? Can you imagine the newspapers tomorrow!'” She breaks out in laughter. Even now, owned by separate conglomerates, peace prevails. At the men’s shows in January, just hours before her own curtain call, Fendi found time to support Alessandro Michele from his front row at Gucci. “Alessandro started out working with me,” she says. “He’s very good and I support him and I like him.” While Michele continued expanding his new universe at Gucci, it was Fendi who became the talk of Milan’s fall/winter 16 shows. Her loungewear-centric collection didn’t just send the Fendi man down a more directional path for the house, but epitomized a menswear season high on feelings of freedom.

De-confining the body, Fendi applied her trademark tactile textures to swathing coats and roomy trousers, loosening up the silhouette and streamlining the masculine form in garments that fused fur and textile in one fluid sweep. She was embodying our culture’s renewed attraction to home life. “We can be everywhere from home now, hyper-connected to everything. But at the same time we feel that we want to be protected from a world that’s so difficult at the moment,” she explains. “It was the idea of something you could feel cocooned inside—and protected. Something to make your life more intimate.” Her loungewear muse? It had to be Hugh Hefner. “He’s been free. He wasn’t afraid to be controversial, doing porno but bringing it to an arty level.” The perhaps unusual poster boy would explain the surprising sexiness of a collection rooted in homey comfort. “For me it was related to fantasy more than reality. An oversize coat can be much more revealing than a tight one,” Fendi says, a twinkle in her eye. Sexy, of course, is an idea often debated when it comes to men in fur. For Fendi, the constellation has always been about the power historically associated with fur by male rulers and warriors before it became a symbol of femininity, she explains, “because men started buying fur for women to flaunt their own power.”

“So I like very much now that men are wearing more fur than women. It eliminates all these status symbols of women being the property of men. It’s an element of this new kind of garment exchange.” To Fendi, the waves of gender-fluidity currently flowing through fashion and pop culture hardly feel like a tsunami. “I’m not really the kind of person to represent the female fashion addict, because I’ve always worn more men’s clothes than feminine clothes,” she says, a mannish navy jacket draped dramatically over her shoulders. A handsome woman, she’s in dark pleated trousers, a navy jumper, and a yellow silk scarf tied tightly around her neck. Come to think of it, she’s a lot like the building Fendi now occupies: beautiful but strict, warm but commanding. You wouldn’t ask her age (and you wouldn’t find it on Google either), but her story goes something like this: Silvia’s grandmother Adele Fendi opened a fur store in Rome in 1925 alongside her husband, who died soon after. “She decided she didn’t want to live in a bourgeois way with her daughters, so she kept going at it and she acted like a man.” For Silvia’s mother Anna and four aunts, feminism wasn’t something you thought about—it was a way of life.

“They didn’t have time to go around the street and be feminists in that way,” she says, gesturing like a protest march, “but they were very active because they were strange women for their time.” Taking on the role of the matriarch, Anna raised her daughter outside the gender-specific norms of the time. (Her father, Silvia laughs, “was at home with headphones on listening to classical music, trying not to listen to all these women around him.”) Growing up, the brand now under the successful direction of her mother and aunts, her wardrobe was dark and muted. “I don’t think I ever asked for a pink dress.” She joined the company in 1987, and when LVMH bought it in 2001, she took over as menswear and accessories designer creating bags such as the Baguette, which is credited with launching the age of it-bags. (Karl Lagerfeld has designed the women’s ready-to-wear since 1965.) “I think freedom is the best way to grow up,” Fendi says. “At least that’s what I always tried to do with my children.” She has two daughters, Leonetta Fendi, 19, and jewelry designer Delphina Delettrez, 28, as well as a son, Giulio Cesara Delettrez, who’s 31. “I wasn’t shocked when I used to come home and see my son dressed like a ballerina, playing with his sister. I have the pictures,” she smirks. “I thought it was amazing!”

Speaking about her own childhood, Fendi says she’s noticing clear parallels between then and now. “For years women had to demonstrate that they weren’t this overall idea of what people thought women should be. What’s happening now is the opposite. Men are starting to be liberated from those street rules, and it’s amazing. The idea that girls have to play with Barbies and boys with guns, I think it’s disgusting,” she shrugs. “It’s something that has to change from the beginning, not just in fashion. But fashion can start to educate people in freedom, to be respectful and not to judge people because of what they wear. Fashion is going towards individuality and this exchange of roles is part of that.” Few people’s thoughts on the future of the industry weigh heavier than Fendi’s. Born into fashion royalty, it practically runs through her veins. And following a winter of surprise designer exits amidst the debate of an overworked fashion system and dramatic headlines such as “Why fashion is crashing” (British Vogue.com) and “The new world order” (The Business of Fashion), her opinion speaks volumes.

“When you said you liked the collection, I felt happy but very worried because then the next one has to be more than that,” Fendi admits. She would like to reduce the number of shows in the year, considering the fact that the seasonal fashion cycle has to respond to opposite climates at the same time, which more or less defeats its point. “Probably one day it’s going to be just one show. I personally think having more time to sell wouldn’t be bad. Give people time.” Whenever Fendi launches a bag such as the Peekaboo, it takes ten years for it to become a classic—the same amount of time it takes for a young designer to establish a new brand. “Accessories don’t go out of fashion the way clothes do. First you sell to the fashion addicts, but little by little people start to follow. People have to have time. At Fendi our most iconic fur coats you can buy at any time. It would be stupid to change them every three or six months.” But it also comes down to over-exposure fueled by social media, Fendi says. She keeps what sounds like an Instagram goldmine: a secret, private account for her team of fifteen designers to use as a digital mood board, although her daughter opened a public account for her only a week before our interview, @silviaventurinifendi. “Every day I say, ‘I think I will close it. I don’t know what to put on it. I don’t know what to write underneath it’,” she sighs, fiddling with her phone. “Ah, I’m on 232 followers today!”

Fendi’s vision for the future of fashion is to apply the longevity of accessories to clothes by increasing the artisanal quality of garments and create enduring pieces, which will appeal to people more than seasonal throwaway copies from the high street. But she says fixing the industry is also about recognizing the individual expertise of brands. “Now there’s not so much ‘the trend of the season’—everybody is doing very personal work. If you go to Fendi you know you’ll find beautiful bags and fur coats, at Saint Laurent you’ll find the tuxedo, and if I want to find prints I go to Prada, because they’re always very beautiful. Not everyone can do everything. That’s what I think. It could be a good move for fashion to do a bigger collection twice a year.” And get rid of the pre-collections? “Yes. Of course it would be ideal to present and sell it right away—maybe not the entire collection, but the beautiful basics.” For the head of the Fendi dynasty and one of the most coveted luxury brands in the world, luxury isn’t about abundance and glamour. It’s about freedom. “Nothing else. When you have time to think and choose, and have possibilities. When there’s not just black and white, but also grey, which can be a beautiful color,” she says. Does Silvia Venturini Fendi feel free, then? “Some days, yes, some days, no. Sometimes I feel like I have too much. Sometimes I feel like I have to work for the things I have, so sometimes I don’t feel totally free,” she pauses. “But I know that I’m free.”

Credits

Text Anders Christian Madsen

Photography Olivia Rose

Styling Bojana Kozarevic

Hair Nicole Kahlani at The Book Agency using Kiehl’s Since 1851

Make-up Danielle Kahlani at The Book Agency using Bobbi Brown

Set design Kimberley Harding

Photography assistance Marcus Sivyer

Printing Labyrinth Photographic

Models King at Named Models. Kyle at D1. Carvell at Models1. Mahad Abdulle. Terry Dixon.