i-D Hair Week is an exploration of how our hairstyles start conversations about identity, culture and the times we live in.

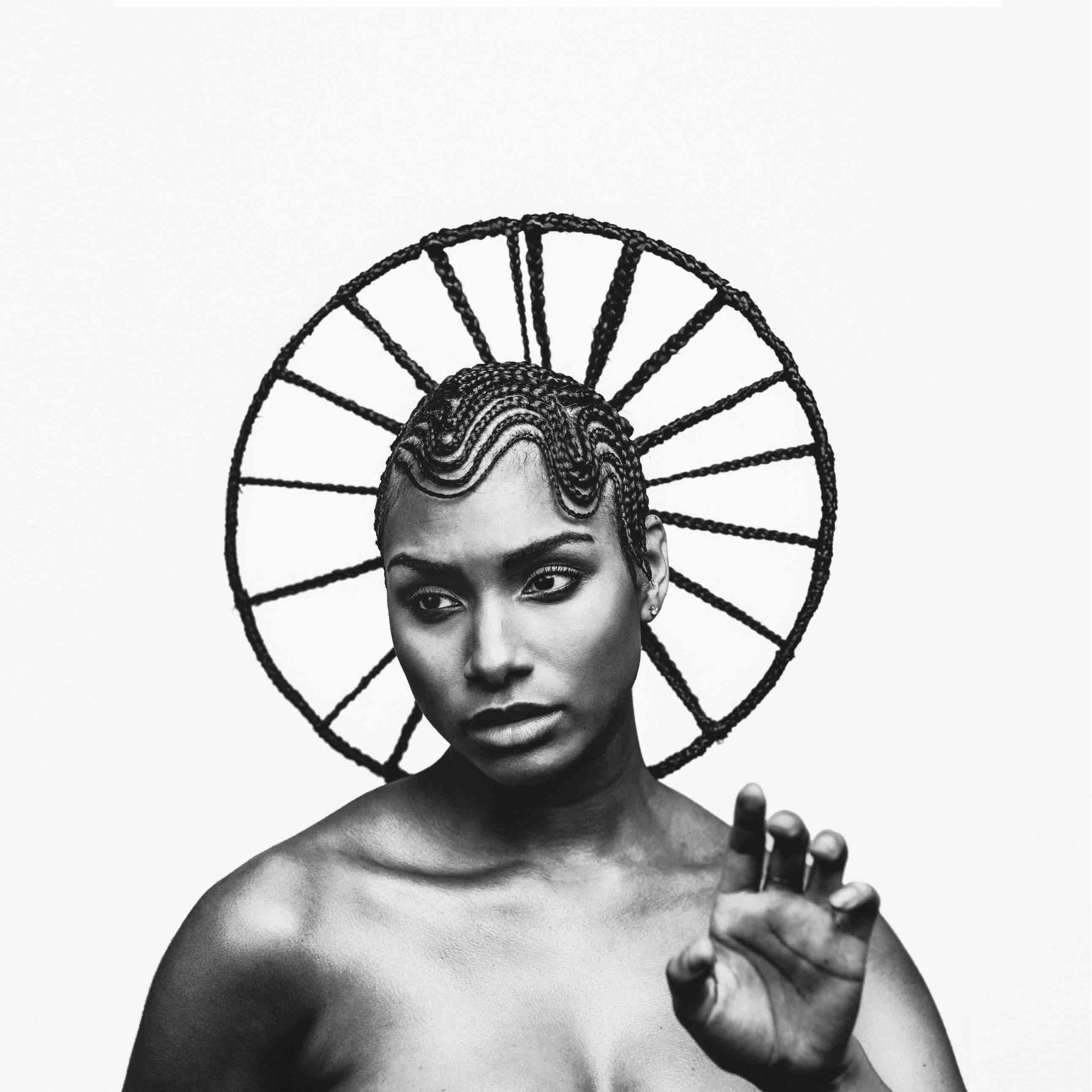

When Solange Knowles made her debut performance on Saturday Night Live in 2016, the stage glittered, quite literally. The R&B singer’s black hair was braided into a finger wave halo beaded with hundreds of Swarovski crystals.

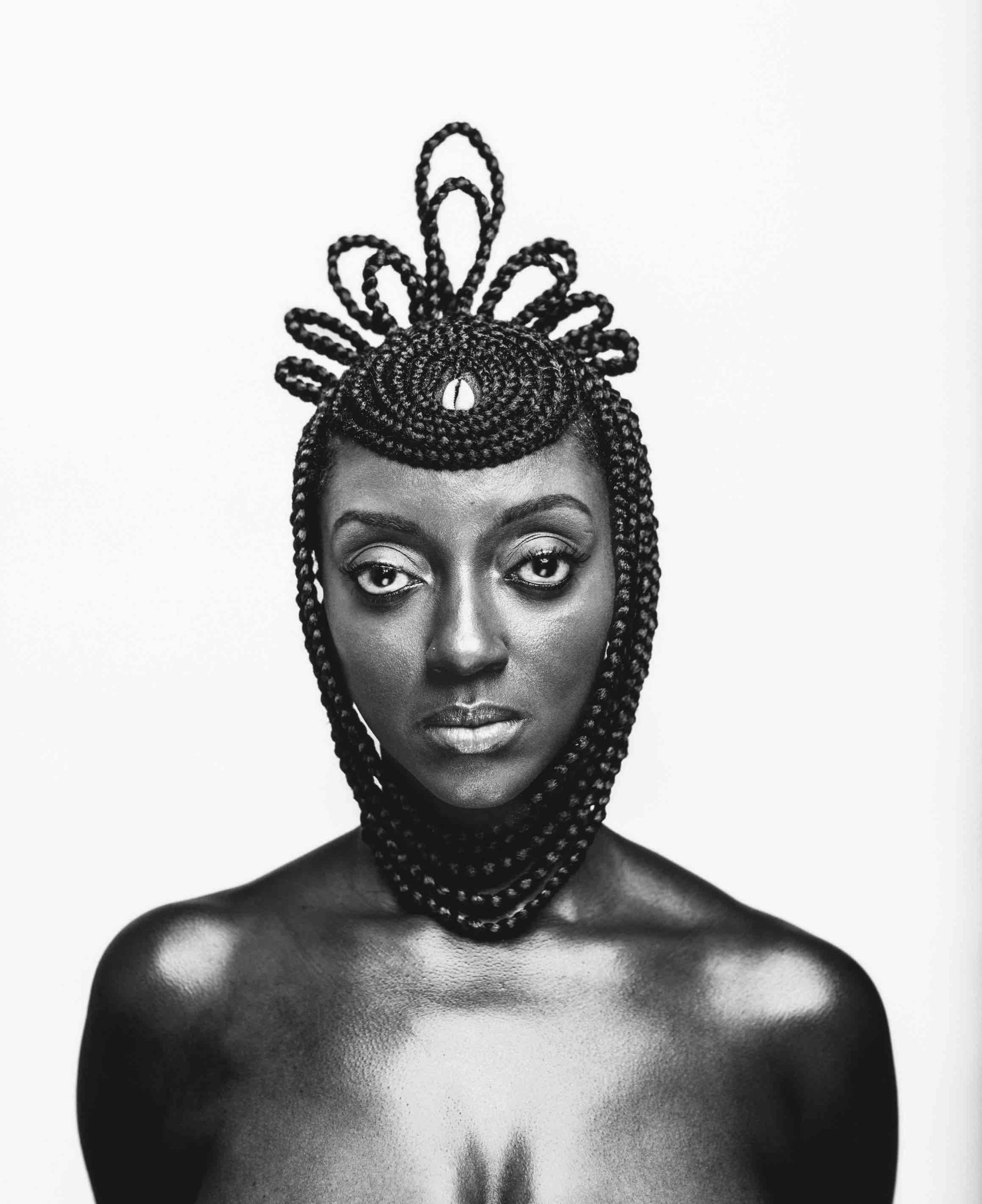

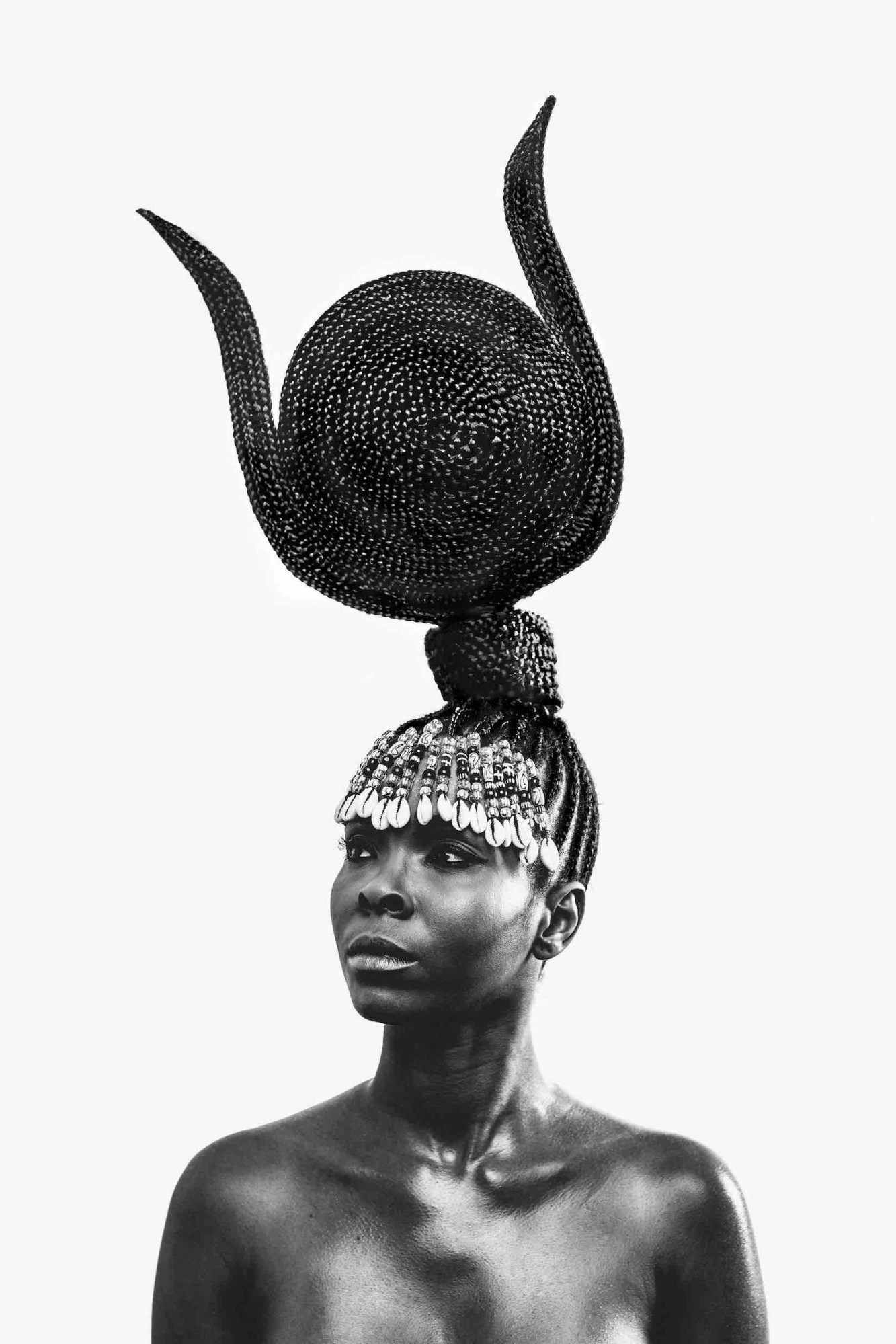

The artist and hairstylist behind the instantly-iconic look is Shani Crowe. Knowles had asked the 27 year-old Chicago native to recreate Fingerwaves Saint, a black and white photograph of a black woman sporting the hairdo. “The armature took 10 hours to make and beading it with crystals took 40,” explains Crowe, who now mostly only do the hair of black women she knows. “For me personally seeing my work on her while she sung Cranes was surreal.” The song, according to Crowe, holds the same serenity of George Michael’s Jesus to a Child, the song the artist asked the model to consider during the making of the image.

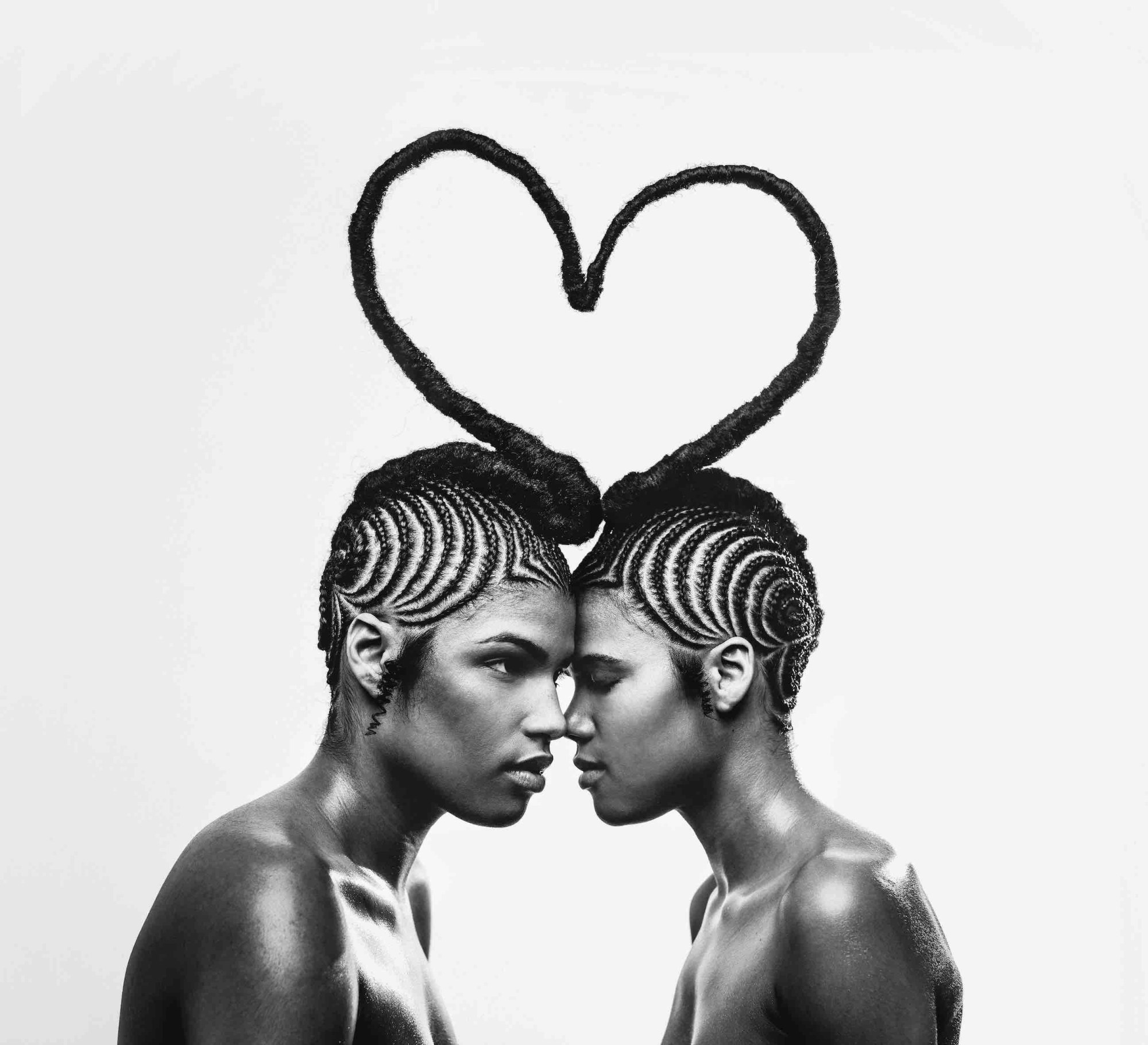

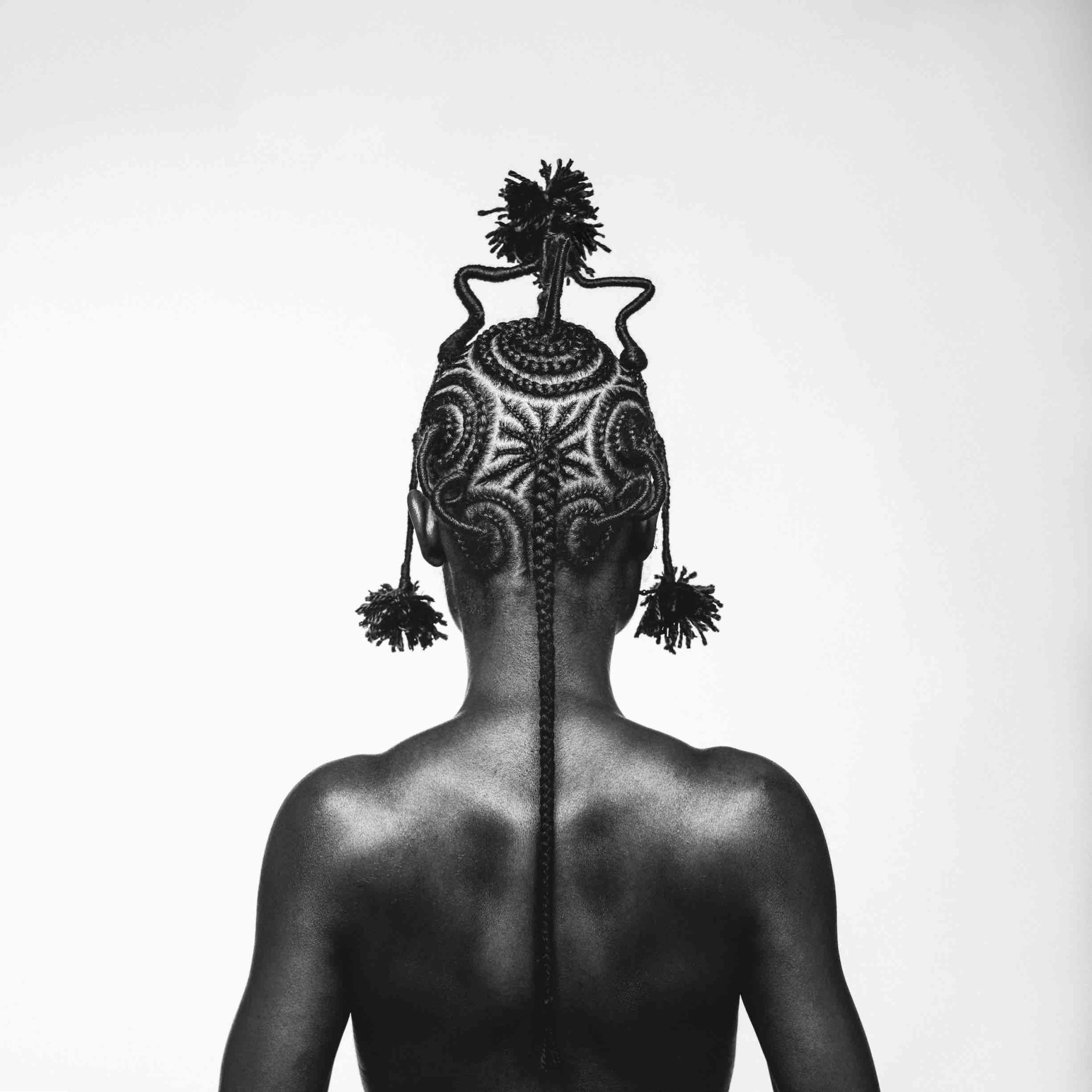

The Crowe and Knowles collaboration makes perfect sense. Both women are deeply invested in elevating black feminine beauty by using cultural markers, and they both infuse their work with a personal kind of Afrofuturism. Crowe’s photographs and Solange’s music defy dominant aesthetic tropes by elevating the likenesses of black women. In deciding to use black hair braiding as a point of departure in her performative photography practice, Crowe celebrates Afrocentric beauty inspired by life on the South Side of Chicago, popular culture, and traditional African braiding styles. Images like The Breath We All Share, which was on display in her Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts solo show, BRAIDS, also evoke a sense of black femme nostalgia. The picture recall the fondness of black women getting their hair did at home and later at beauty salons.

“The opportunity for deeper understanding among black women allows a paradigm shift,” writes Crowe in an introduction to the show, “where a group seen as a double minority has an inherent advantage. By referencing an intergenerational collective memory, seated in the crest of the Black feminine experience, I create an instance of privilege.”

We speak with Crowe about the art of black hair braiding, the inspiration behind her images, and how she strides to please her real-life clients.

, Shani Crowe

How did you start doing hair?

I’ve done since I was a child and I’ve had clients since I was 11 years old. I’ve always been able to do my own hair and doing my own hair got me clients for braids, weaves and presses.

Who taught you how to braid?I started trying to braid when I was seven. My aunt and cousin would do my hair. I looked up to them and trusted them to beautify me. I thought braiding was a rite of passage, because all the cool women in my family knew how to braid. I really wanted people to trust me to do their hair because for black women, it is an honor to trust someone to do your hair. I would practice on a doll with really spacey hair. I remember disassembling this cheap Halloween wig so I could glue tracks into my doll’s hair and braid it. So I picked it up, visually and by paying attention to the feeling of getting my own hair braided, but also through trial and error and passion and desire.

, Shani Crowe

When did you decide to turn black hair braiding into art?

I’ve always been an artist. I draw, make collage and experimental video. At first, I never really thought about braiding as a part of my artistic practice. Mainly because people didn’t value it as much as other things I did academically or artistically. I took on those misgivings about braiding and wasn’t really as proud of it. It was more of a side gig for me. I thought back to when I was just starting to take clients and how excited I was about being able to create designs on people’s heads and I remembered that I wanted to do a photo project where I would do crazy braids with color. It was like 2001 and technology wasn’t up to par at that point, and I would have been shooting with like a one megapixel camera. I got a grant and I thought back to that project and decided to create it which led to BRAIDS, my photography exhibition at MoCADA.

Black women use braiding as an act of self care, beauty and a gesture of community…

Braiding is absolutely a gesture of pure love. My aunt and cousin, as my family members, as people who care about me, wanted to make sure that I was groomed and presentable. I carry that through my client work and art practice. Now, I do a lot of my friends and family’s hair, these are people who I’ve known all my life and I want them to look and feel their best. It’s a pleasure to do this. Braiding is something that [has been] passed down generationally as a part of my life and culture.

, Shani Crowe

The braided hairstyles you create are elaborate. What’s the process like of creating the designs?

I start by sitting and meditating about what I can do with hair. I often trace with my fingers in the air what I want to do. None of the styles are sketched out, they are concepts that I feel my way through organically. In Above All, I knew I wanted to join two women by braiding their hair into one heart. The two women in the photo are actually sisters.

, Shani Crowe

Works like Above All symbolize through black hair different representations of beauty and sisterhood.

Yeah, Above All is about love and sisterhood. The concept was love between sisters but not necessarily blood sisters. In black culture, especially the Afrocentric community I come from in Chicago, the I Am, We Are mentality of the village that sees women as sisters inspired the hairstyle and photograph. Those familial relationships, both on a micro and macro scale, are difficult because you sometimes fight with your sisters but above all there has to be love.

Do you always try to use symbolism in your work?

The symbolism is intentional. Some of the work is less obviously symbolic but each hairstyle gestures toward personal black nostalgia surrounding the beauty of black women. Before black was in again, for people who are not a part of the culture a lot of the natural ways black people show their beauty was thought to be ostentatious. I think on any level, from the gaudy to ornate to the simplest hairstyles, black people present themselves in a certain way. And because hair is such an integral part of our outward display of our beauty and culture, when I am doing client work I always feel like I am at the whim of the client’s approval. It’s part of the process I don’t take for granted. A hairstyle isn’t successful if a client isn’t pleased.

, Shani Crowe

Fingerwaves Saint inspired the look Solange wore. What does that particular braided style mean to you?

I didn’t revere braids as a high art because of what other people thought about them so with Fingerwaves Saint I wanted to depict them in the highest form, which is as a divine being, the height of how someone can be represented. I did the model’s hair in the finger wave pattern because growing up I thought it was genius how [beauticians] were able to gel people’s hair into those waves and keep them like that. But you know for everybody else outside of the culture fingerwaves were considered ghetto. But what they didn’t see is it honestly takes a lot of work to create and maintain that hairstyle.

What kind of statement about blackness are you looking to make by highlighting black braiding as art?

My goal is for black women to embrace themselves without having to appeal to any other standard of beauty. I want them to know that they can be themselves. There is so much in our culture we overlook because we have been taught not to respect it because it was said not to be beautiful. I’m hopeful because now I see black people doing all kinds of crazy, amazing things with their hair. In my heart, I just want black people to be black and not let other people dictate when our hairstyles or culture are in style.

, Shani Crowe

Credits

Text Antwaun Sargent

Photography Shani Crowe