What sticks in your mind about the YBAs? The money? The outrage? The newspaper headlines? The art? Is it telling that art comes last in that list? Probably. It was never about the art, really; it was all about the money, the outrage, the headlines. Of course not always, but those are the things that dominate the immediate memory; the story of the YBAs at the height of their pomp and pomposity was told in the tabloids as much as it was in the galleries.

Despite their 90s heyday feeling like a lifetime ago, the YBAs never really went away. They’ve somehow managed to echo their controversies down the years. In 2014, Tracey Emin sold My Bed for £2.5 million ($3.7 million), which seems a lot, but it’s a figure that pales in significance next to that great sparkly nail in the coffin of the YBAs: For The Love Of God. In August 2007, as the great financial crisis began in earnest, Damien Hirst auctioned off a diamond encrusted platinum skull for £50 million ($73 million). This year, Hirst opened a museum to show off the art collection that making diamond encrusted skulls for a living allows you to buy (and he’s still making blasé comments about money and art that try to justify his career). Sarah Lucas represented Britain at the Venice Biennale last summer, and presented a sculpture with a cigarette flowering out of a plaster vagina. Emin, fresh from endorsing the Conservative party for office, married a rock in her garden earlier in the year. Nothing changes, does it?

The controversy became the art. The hype became the form. The outrage became their oxygen. But like Tony Blair — whose trajectory they mirrored, whose society they molded and represented, whose apolitical money, money, money schtick they were ciphers for — they increasingly preach to empty rooms, increasingly shoved out of the cultural conservation. The story’s been told a thousand times, right, and we’re all pretty bored of it?

But Artrage, The Story of the Britart Revolution, a new book by Elizabeth Fullerton, proves that there’s still a little bit more juice to be squeezed from YBAs. The book itself is interesting, an oral history, told by pretty much everyone who was there. And is usually the case with these kind of books (if you remember the 90s London art scene you weren’t really there or something) some who were but weren’t relevant, and some who were relevant but weren’t there. It tells the story well, such that a sceptic like me — who thinks they already know everything, who went to Goldsmiths and bought the fried egg t-shirt — was left enlightened (shudder).

There is of course a lot to dislike about the YBAs these days; they’re fat, old, bloated, irrelevant, weighed down by the gold coins rattling around in their pockets and the egos rattling around in their heads. We’re far enough away from the big bang of their artistic revolution to be bored of them, to have moved on to new things, but not far enough away from their descent into irrelevancy to reappraise their legacy. The real success of Artrage is that we are actually now far enough from their first breakthrough, in 1988, to reappraise at least the movement’s beginnings, if not quite what it grew into. It’s no surprise then that the book’s early sections are its best, filled with energy.

Is it hard to imagine a time when art wasn’t in the national consciousness in the way it is post-YBA? In 1988, the year they broke out, there were few commercial spaces. Lisson and Anthony d’Offay of course, Maureen Paley was mounting exhibitions in her house, Charles Saatchi was only showing works by German and American minimalists and conceptualists. There were the institutions of course, the ICA, The Tate (Britain, no Modern), The RA and the Hayward, but they really played little part in the national discourse, impressive and irrelevant, like the opera or ballet. There was art, but no real art infrastructure, beyond the big level. Art was a cultural relic in Britain, the last revolutionary movement to sweep these shores was the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in the late Victorian era. The rest swept through the continent, and London was content to let Paris have the big ideas and New York the big money.

Conceptual art was a con, epitomized by Carl Andre’s Bricks at the Tate, and modern art was vulgar, if not downright evil. COUM transmissions were heralded as wreckers of civilizations in Parliament (contemporary art has always been ridiculed and feared). The Turner Prize, which launched in 1984, was won by Malcolm Morley, Howard Hodgkin, Gilbert & George, Richard Deacon, Richard Long, Tony Cragg. Beyond Howard Hodgkin and Gilbert & George, not the most inspiring of lists, is it? London was not the art world center it is today, it couldn’t be further from the truth, in fact, which is why Charles Saatchi was busy collecting and exhibiting the work of Germans and Americans. This changed in 1988, though.

The YBAs rose out of Goldsmiths and the radical art school program put in place by Jon Thompson, who was disillusioned by the conservatism of art education of the 60s he’d experienced — despite all spectacular Situationist sloganeering of the time. When he became head of the Goldsmiths art department he began to systematically dissolve the divisions between artistic disciplines, and encouraged the students to be artists, to experiment. He got working artists in to be teachers, both young and old, radical 70s conceptualist Michael Craig-Martin rubbed shoulders with the recently graduated Mark Wallinger, performance artists like Lindsay Kemp, and feminist artists like Helen Chadwick and Andrea Fisher. Between them they taught the generation that became the YBAs: Damien Hirst, obviously, Mat Colishaw, whose Bullethole at Freeze set the tone for the whole movement, Angus Fairhurst, Abigail Lane, Angela Bulloch, Ian Davenport, Anya Gallacio, Gary Hume, Michael Landy, Sarah Lucas, Fiona Rae.

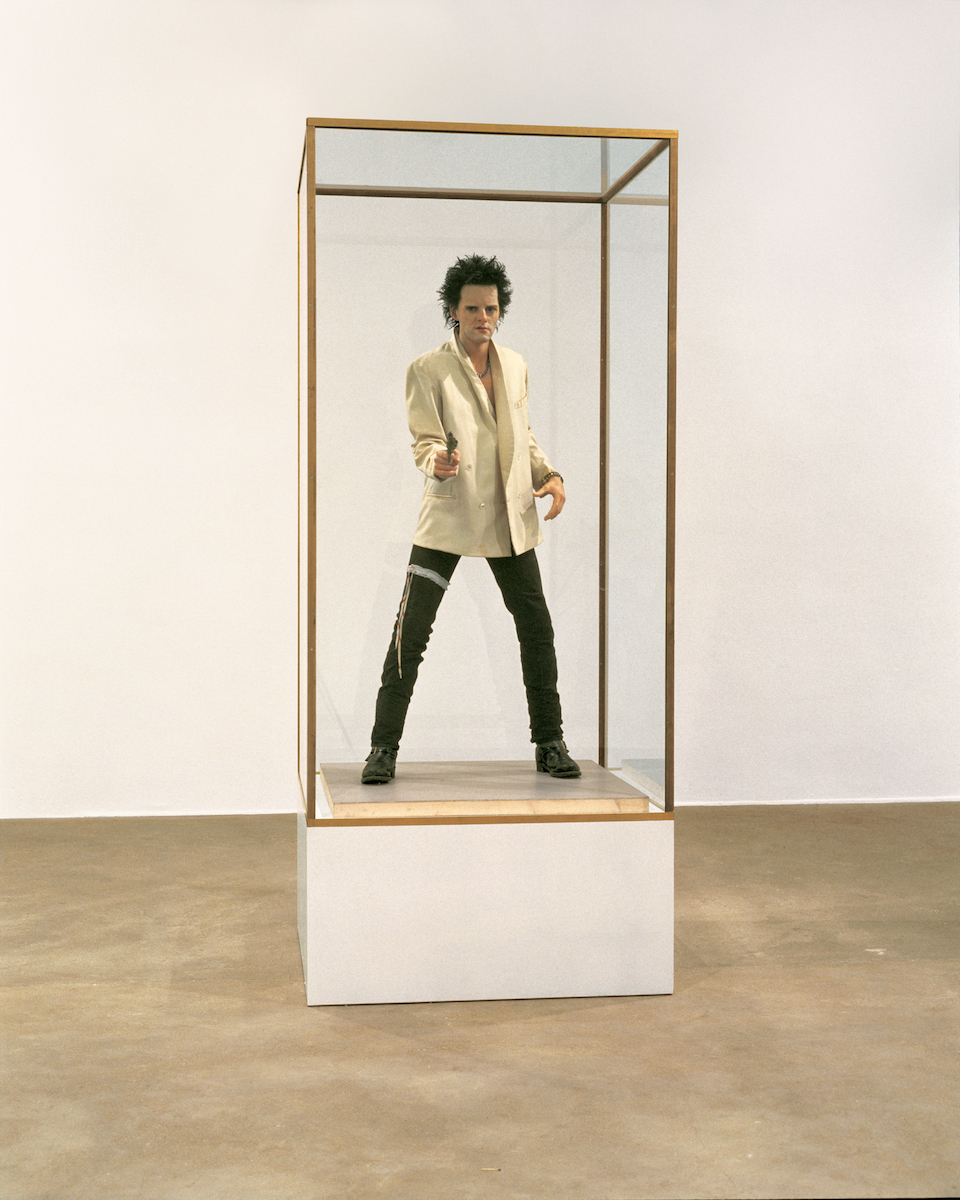

At Goldsmiths the aesthetic of the movement coalesced, growing out of pop’s critique of consumer culture, Warhol’s fetishization of it, conceptual art’s focus on process, Duchamp’s hubristic ready mades and Arte Povera’s focus on the everyday object. Jeff Koons exhibited at the Saatchi in 87, turning on Damien Hirst to his glitzy materialist repurposing of Americana as fine art, paving the way. You can see Damien turning those vitrines of vacuums and basketballs towards his own coffee table existentialist leanings (you can see it right now, in fact, as Hirst is exhibiting his collection of Jeff Koons works in his newly opened gallery space).

By 1988 all the pieces were in their right places, the students, the teachers, the culture (or the absence of culture), and it fused in a landmark exhibition, Freeze, that Damien organized in the docklands and opened that year.

So Freeze arrived in 1988 and the scene came together and the myth was born. It convened the Goldsmiths generation in a disused port office building in the Docklands, was sponsored by property developers Olympia and Young, and the London Dockland Development Corporation, (a controversial body set up to regenerate London’s Isle of Dogs into the global center of capitalism we know and love today). The work was embryonic, most were still students of course, but in Matt Collishaw’s Bullethole it found an emblem: a kind of ironic, nihilistic detachment in the face of violence — a blown up image of a wound in a head — that could equally stand in for the nihilistic violent detachment of society at large, or simply the artists. The nine-week-long exhibition was an immediate success with the art world, their tutor Michael Craig-Martin brought through a succession of gallerists, artists, curators and collectors who would launch their careers. There was an immediate backlash at Goldsmiths from those who weren’t part of the exhibition though; there were protests that centered on their collusion with the LDDC, who many saw as a Thatcherite vehicle for the destruction of the Docklands’ old working class communities.

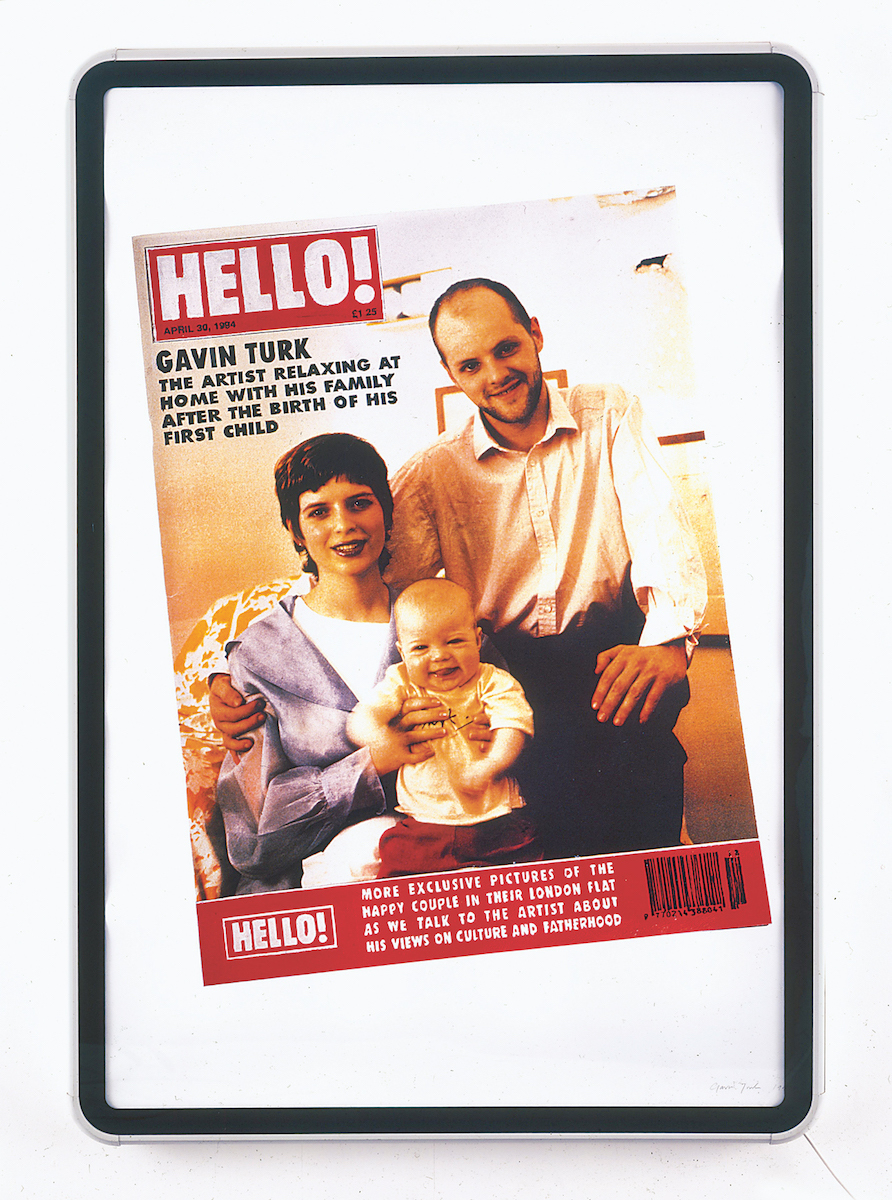

This is the crux of the argument, I guess; whether the YBAs were Thatcherite colluders, or the inheritors of punk’s tradition of DIY building of your own cultural ecosystem. The answer of course is somewhere in between. There was a Thatcherite cult of personality for sure, the artist became a popstar, the artists lived like popstars, hung out with popstars, the artist distilled their ideas down into bright colours and simple shock tactics like popstars. The artist became both Malcolm McLaren and Johnny Rotten, svengali and idol, organ grinder and monkey. Post-Freeze artists became cool in a way they hadn’t been in Britain in before, became working class in a way they hadn’t been before; art became a career in a way it hadn’t been before. Post-Freeze art became electric like punk — a big burst of bright light that illuminated everything anew.

Depressingly for Hirst this was his creative peak; turning the Freeze space into his studio, he moved away from abstract, color-block sculptures, and made his first spot paintings, he made his first medicine cabinets in 89, for his degree show (he even named them after Sex Pistols songs). Soon after, he exhibited, at another series of South London warehouse shows, A Thousand Years, by far his best work, which presents the life cycle of flies, from birth to death, alongside a dead cow’s head and an insect zapper in a vitrine. The rest came soon after, the sharks and lambs and all the other animals from the Ark.

Like punk, The YBAs were best at their newest; they peaked creatively too early, beyond the initial energy all that was left was the controversy. They stylistically coalesced too quickly, too young — got big and rich and famous too young, as well. They didn’t have anything left to grow into.

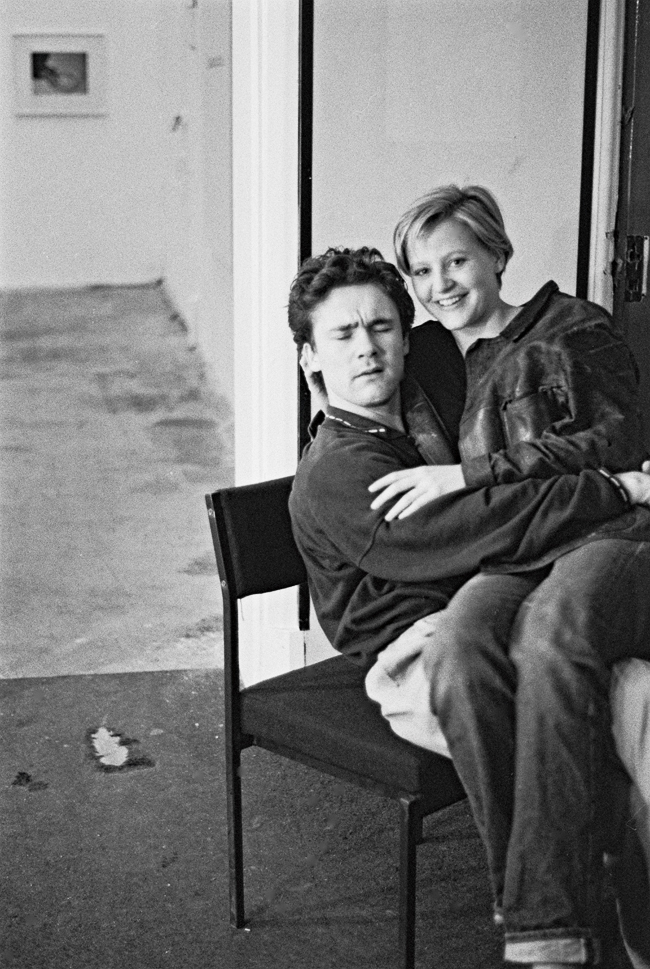

Artrage thrills in the soap opera that followed them around, in their popstar-ness. It’s great at storytelling, and it revels in the gossip, money and infidelity, but it leaves you cold on art. That’s not the book’s fault, but the YBAs’. They changed the art world, or rather, created it — but beyond a few works, what lasting impact has it had? Can we reappraise it?

They turned art into pop, but equally “pop” is a kind of veneer, a sheen, a style not a substance, a dance not a discourse. By turning art into pop — not pop art but Pop — it destroyed them in a way. We’re bored of the YBAs in a similar way we get bored of all pop stars. There’s the reformations, the spats, the descent in middle-aged conservatism, whatever.

That’s why it’s relevant to reappraise the beginning, the first shows, the initial impact. They created a model many other aspiring art school grads have utilized: big empty spaces in down-at-heel decidedly un-glam spaces, a frisson of danger and the safety of a chauffeur driven car. That’s what they really gifted us.

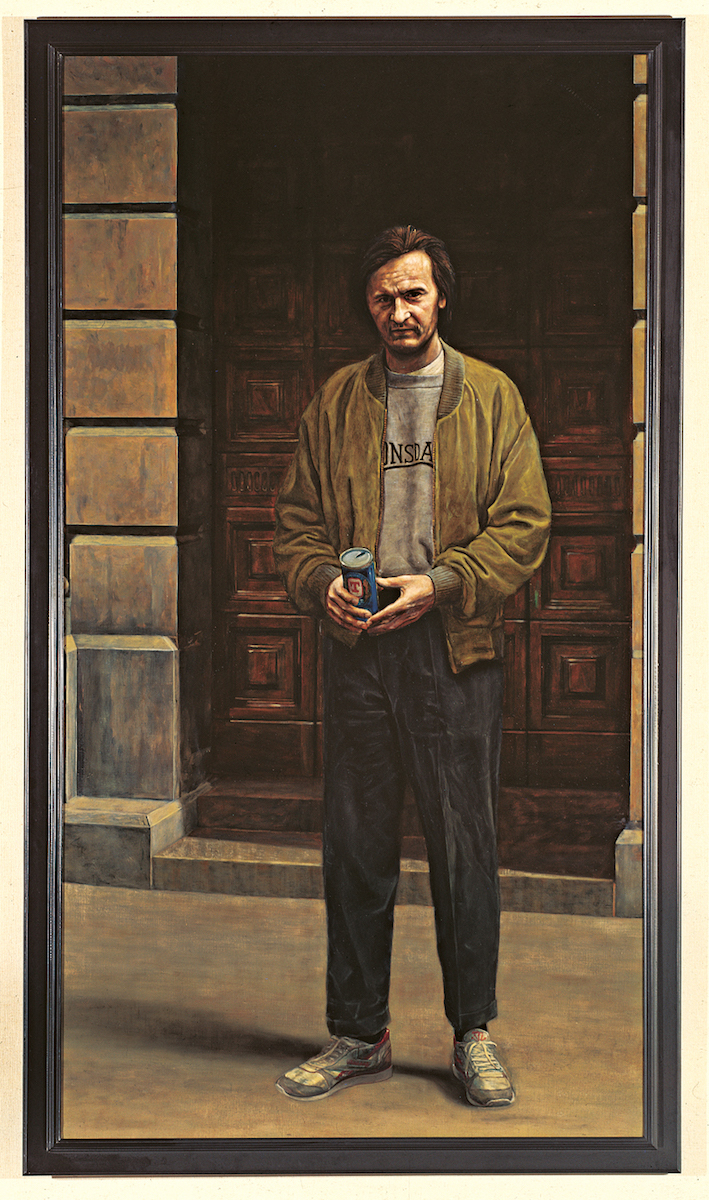

And this of course doesn’t mean that nothing came out of the YBAs which wasn’t artistically exciting or interesting or challenging, just that the stuff that did was the least typically YBA-y: Mark Wallinger, the Bank group, the scene around City Racing gallery, Gillian Wearing, Jenny Saville. There’s no doubt that they’ve improved the cultural landscape of the city as well; Frieze, The White Cube, Sadie Coles, Victoria Miro, Maureen Paley, all sprung up in their wake, bringing with them another generation of international galleries, like David Zwirner, Gagosian, Hauser & Wirth. London rivals New York as the centers of importance for money in the art world.

What Artrage allows us to do is look back to the years of incendiary explosion, 88-91, with fresh eyes — years that, like punk, changed everything and made everything possible. But like punk, its key proponents are now old, past their best, surpassed culturally and critically (if not commercially), increasingly irrelevant.

They were defined by their shallowness and superficiality, discourse-less, free from theory, but discourse has had its revenge.

They might’ve had no discourse, that might’ve been their appeal, but discourse has had its revenge on them. They built the art edifice and then were supplanted by an age of identity politics, internet feminism, accelerationism, and every other ISM reared their big ideological heads again, as if in protest of the hollowness of the YBAs.

I suppose we should reverse that opening line; what do you think about the art of today? Post-crash, there’s not as much money, there’s not as much outrage, no newspaper headlines. Just art. That could be their lasting legacy.

Artrage! The Story of the BritArt Revolution by Elizabeth Fullerton is published byThames & Hudson this month.

Credits

Text Felix Petty

Images courtesy Thames & Hudson