“We dipped our fingers in the fountain of youth,” is how Jamaican-Irish playwright Linda Brogan explains the 2017 archaeological excavation of The Reno, Manchester’s original nightclub for mixed-race youth. Opened in the early 1960s, and famously visited by Muhammad Ali, the funk and soul venue enjoyed a heyday in the 1970s, only to close in 1986, and be demolished a year later. Overgrown by grass in the multi-ethnic neighbourhood of Moss Side — where Manchester’s Irish, West Indian and African communities have traditionally lived — it was all but forgotten. Until now.

“Once you got in, it was like you were home,” remembers Barrie George, a retired Manchester City Football Club steward, who partook in the club’s excavation.

Stigmatised by the 1930 ‘Fletcher Report’ (a controversial paper that described children of mixed heritage as suffering from inherent physical and mental defects) people such as Barrie and Linda found themselves caught between two different communities. “When we’d go to town, white people would say, ‘black this, black that,’ then we’d go out in Moss Side and the Jamaican people would go, ‘you mixed race, two nation, people with no countries,’ so it was like we were battling with two,” explains another Reno regular, Steve Cottier, his words echoing around the vast expanse of Whitworth Art Gallery’s upper floor. We’re here because, starting on 15 March, the gallery will be the site of a year long residency, during which Linda, and twelve former Reno regulars, will explore the club’s historical context and attempt to strengthen its legacy.

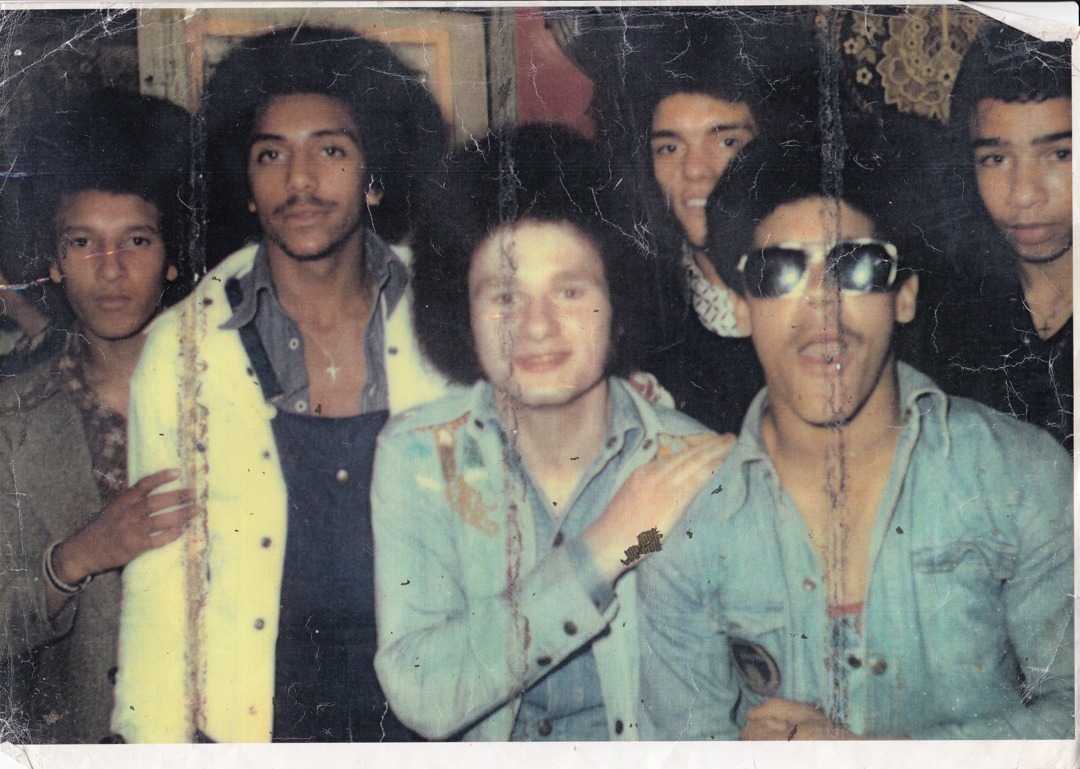

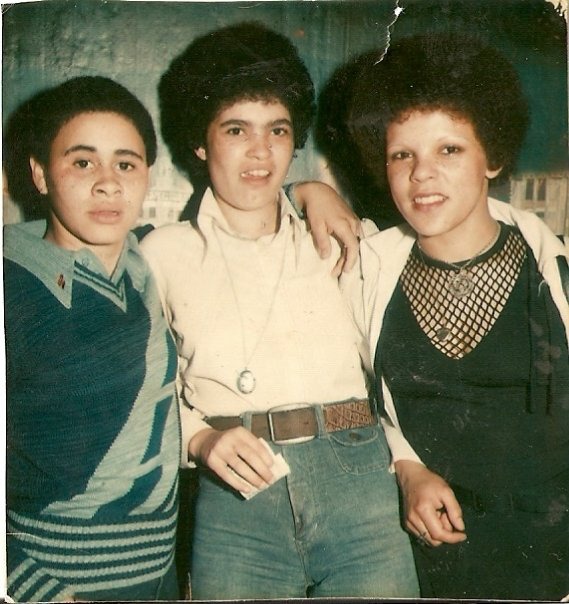

As the Reno regulars reveal, the club’s music was a way to channel their frustrations. “You’d have a lovey-dovey song and then you’d have Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On,” remembers Philip Collins Snr, another member of the ‘Reno 12’, who are gathering their memories and photographs for the forthcoming exhibition. “When I moved over here in 1961 all the clubs in Moss Side were playing reggae but back in Jamaica I grew up on American music. Thankfully the owner of the club recognised that what I was playing was making the club popular,” explains Persian, the Reno’s former DJ. Indeed, the unusual records selected by Persian and fellow DJs, such as Coolie and Hewan Clarke, soon attracted the likes of Simply Red musician Mick Hucknall and Factory Records boss Tony Wilson, with Clarke later being asked to play at Wilson’s Haçienda night club. But most white people wouldn’t come unless invited: “They weren’t your average white person,” Phillip asserts. “They had some association to black or mixed race people.”

And so, mixed race youths, who weren’t welcome elsewhere, continued to make up the fabric of the Reno. The friendships that were made began to extend beyond the club too, with Steve keen to tell me that the Reno even birthed a football team, Afroville, that, after the weekly Sunday afternoon game against the city’s other teams, would head back to the Reno for a drink. “We’d be stinking of grass and mud, but we didn’t care,” Steve says. “People would ask us, ‘how d’you get on?’ and we’d say, ‘we won!’”

Now mostly in their 60s, though still sprightly, sharply dressed and excited to share their stories, the regulars tell me that the Reno was open day and night, long past its official license, and usually closing at five or six in the morning. Many patrons would be in there every day, playing dominoes in the ‘gambling room’ or smoking weed. Police raids were frequent. “There was a way out the back, but there was just one door, this one passageway and I remember one police raid we all just dropped our spliffs when they put the light on and ran, everybody really laughing,” Linda recalls.

The Reno’s reputation soon spread nationwide. “In the mid-70s when it was at its height, it was the number one soul club in all of Great Britain,” asserts Phillip. However, unlike arguably Manchester’s most famous nightclub — the predominantly white working class Haçienda — the Reno hasn’t really been remembered by the history books. Linda felt that this was a travesty and began an 18 month long mission to secure funding for the excavation of the club. Funded by the National Lottery, and completed with the assistance of Salford University’s Centre for Applied Archaeology, the club is finally getting the recognition it deserves, bringing many of Moss Side’s residents together, with the children, grandchildren and even great-grandchildren of those who attended the Reno coming to help with the dig.

Flared trousers, combs, lipsticks, perfumes, wallets, record bags and even weed were recovered during the excavation, culminating in a party played by four of the still living Reno DJs. For the volunteers who make up the Reno 12, the dig became almost an addiction, as well as catharsis. But they also see the exhibition, which will include a replica of the club as well as artefacts from the archeological dig, as playing an important role in preserving the area’s history. “The people living in Moss Side now, who’ve moved into Moss Side, can look at the archives we’ve got, and think, ‘oh yeah, there’s something substantial down there’,” Barrie says.

While the dig was groundbreaking — the first excavation of a nightclub in living memory — the year’s worth of filmed memoirs which preceded it are also a treasure trove for any discerning social historian. In one interview, Whitworth Reno 12 member Myra Trigg talks about being a 17 year-old mother leaving her pram outside the club, speaking volumes about how safe the area was prior to the ‘Gunchester’ drug related violence that befell Moss Side during the 90s. The interviews also proved to be a viral hit: “Without us saying anything, without any marketing, 45,000 people watched our videos,” Linda tells me.

Meeting again, after sometimes decades of not seeing each other, means many of the Reno regulars have plenty to talk about, finding themselves with different perspectives on subjects such as the area’s 1981 riots, which preceded the downturn of the club. For Linda, the project has been an opportunity to take ownership of the complex narratives surrounding black and mixed race identity, often misunderstood or mishandled by those without firsthand experience. But the Reno, she stresses, is predominantly a tale of joy, and one that’s now being told as it should be, by the people who loved it most: “We had an absolutely fabulous time down there — and I knew if I just held onto that, I knew it would be alright,” she sums up and calls for a break. It might not be weed anymore, but the Reno 12 still like a smoke.

The Reno residency starts on 15 March 2019 and concludes in March 2020. More information can be found on the Whitworth Art Gallery website.