“Tea or wine?” Azzedine Alaïa asks, generously offering me options from his chef’s cupboards. I’m here to interview the notoriously private legendary designer; but first, he says, we will have lunch. We sit side by side at the head of a fourteen-seater table, surrounded by his team, in a huge open plan kitchen at the very heart of the Alaïa headquarters. Alaïa eats lunch here every day with his colleagues, and anyone else who happens to pop by – supermodels, stylists, artists, editors… this is where the discussions happen, the debating and the laughter. It is the life-giving heartbeat of his world.

I look around the room, acutely aware that this is not a table of lunchtime wine drinkers; people have things to do! “Tea please,” I reply. “Delicious,” I say, sipping my Bergamot tea. We look at the label. “It’s English,” Monsieur Alaïa chuckles, “you have come all the way from London to Paris to drink the most delicious English tea!” Even the mundane is exquisite, with the Alaïa touch. Over a delicious three-course meal of chilled pumpkin soup, roast beef and vegetables, followed by caramel cake with cream, Alaïa demonstrates the warmth and sense of humour he is loved for. Born in Tunisia in the 1940s, he originally studied sculpture at L’École des Beaux-Arts, something that is immediately evident in almost every piece of his clothing. Soon after, fashion caught his eye and he convinced his sister to teach him to sew. He found his way to Paris in the 50s and after working as a couturier for Parisian high society, he did stints at Dior, YSL and Guy Laroche, until his friend Thierry Mugler, convinced him to set up on his own in the early 80s.

Alaïa has never courted the press and is not one to adhere to the increasing pressure and pace of looming seasonal deadlines. In the face of an industry that, these days, seems to be chasing its tail from one season to the next, he is an exceptional breath of fresh air and proof that integrity, and quality, still goes a very, very long way. When Alaïa started, his contemporaries were putting on huge seasonal spectacles, but he always chose to show quietly, a few days after fashion week finished, in his own space – something he still does to this day. If he doesn’t feel ready, he decides not to show at all. This season was one of those times.

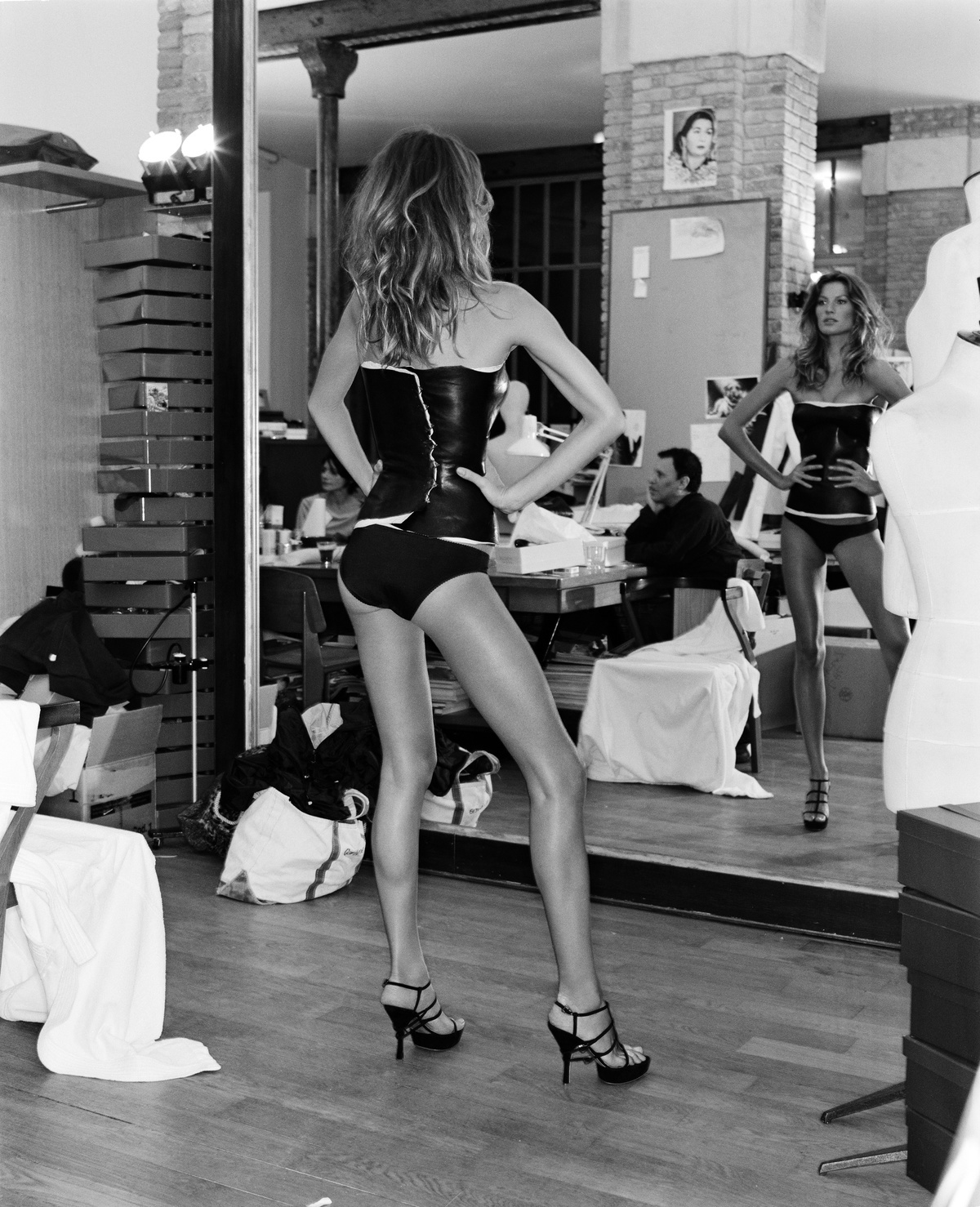

In the 80s, while everyone else was designing clothes that were unisex and oversized, Alaïa’s shapes were, and still are, a product of his fascination with the female form. Each piece accentuates a woman’s body, enhancing the good and hiding the not-so-good, pulling in the waist and smoothing the bum and hips, treading that very subtle line of sexy without being vulgar.

Alaïa was the designer every supermodel made themselves available for; they turned down other jobs to walk in his shows, simply for the promise of being initiated into his world. Naomi Campbell and Veronica Webb struck up family-like relationships, staying on and off at his house for years.

I have been so lucky to be surrounded by so much beauty in my life. These girls started their careers here, they gave me their youth, their beauty and I am so grateful for that.

“I have been so lucky to be surrounded by so much beauty in my life,” Alaïa says, his eyes lighting up. “These girls started their careers here, they gave me their youth, their beauty and I am so grateful for that.” Alaïa is still in touch with all the original 80s supermodels. Naomi Campbell gave him one of his dogs, a little Maltese called Anouar. While Stephanie Seymour, who put on a show of his work in New York not long ago, always passes through his atelier whenever she is in town. The countless images of Linda, Naomi, Christie and co. in his sculptural bodycon dresses are some of the most iconic of the time and are still endlessly referenced to this day. “I suppose my clothes are an homage to all women and to all the women in my life,” Alaïa says. Many of the shapes he developed over 30 years ago are still being produced in his collections today. There is a magical quality to his work; each piece, without exception, is timeless. Yes, the techniques may change, new materials or hemlines may occasionally be introduced, but there is continuity, and an evolution within each piece and each collection that maintains relevance. “It is extremely important to me that the pieces I make should work now and in all periods,” Alaïa explains. “I am not trying to create a revolution; it’s always an evolution. Once I have the shape or the idea I just develop it. It should always work 20 years from now. That’s what Chanel did and that’s why Chanel is still successful and has lasted such a long time. She had one good idea and didn’t try to change it.”

Easier said than done. But the proof is in the pudding because right now, more than 30 years after his debut, these are very interesting times for Monsieur Alaïa. Only a few weeks ago, during Paris fashion week, he and curator Olivier Saillard opened an exhibition, simply entitled Alaïa, at the newly restored Palais Galeria. It is a magnificent display of works from throughout his career: from the metal beaded dress that Tina Turner wore to leopard knit dresses that conjure up iconic 90s imagery of lined-up supermodels to a hooded knit dress that Grace Jones wore, and the list goes on. Next door, the Musée d’Art Moderne displays some of his magnificent gowns, juxtaposed with a jaw-dropping backdrop of Matisse’s Nymphs. “I’ve done plenty of exhibitions, so I wouldn’t say it’s something I’ve waited for my whole, life but of course it means something to me to have it here in Paris, finally,” he says. “For me it is important to have it here, because I am here, this is where it should be.” Next on the agenda for exhibitions is Russia and New York.

Alaïa is nothing if not contemporary – he recently designed the red dress Rihanna wore to the Grammys, which is also featured in the exhibition. At the other end of the table, his nephew Montassar is discussing whether or not they will go to the Jay Z concert to which they have just been invited. Rihanna, Shakira, Beyoncé and Alicia Keys will all be there. “I like them all. And they all come here. We dress them all,” he says. (Shakira, in fact, gave Alaïa his other Maltese dog, called Waka Waka.)

Contrary to what has been reported by some, Alaïa did design a new collection this season, but he simply decided not to show the collection to the press – he felt he hadn’t developed his ideas as far as he wanted yet. “There was not enough time this season, I spent a huge amount of time restoring all the pieces for the exhibition,” he explains. Nonetheless there are still new architectural feats in the collection – bonded silks in stretch, to give the look of the lightest material, while drawing in the waist and floating out into curved hips or down to the floor. There are scalloped hems, with petal-like pleats, as well as 3D zigzag hems. These are more like magical sculptures than clothes.

Alaïa has revisited some of his most celebrated ideas, perhaps inspired by working with his archive; there are leather skirts with metal eyelets – something that originally appeared in his first lauded collection in the 80s and are in the show at the Palais Galeria (he was one of the first to work with leather in clothing). There are also classic pieces, like the shirtdress that appears every season, with bias cut layers at the skirt and a slight drawstring at the waist. Even with the simplest item, Monsieur Alaïa is there with his woman, coaxing her into her perfect self.

Every single pattern that is made comes from his hands, he works and works on them until they are perfect. It can take weeks, even months, but they will not be finished until he feels they are ready. “I do the pattern and I do all the pattern- changes,” he explains. “I am involved in all of the shoots, the sales. Then, when others would hand it over, I make sure that the production is absolutely correct. This is my least favourite part, but I do it, it’s very important.” When I ask him why it’s important for him to do absolutely everything himself, he simply replies, “because that’s just the way it is.” When I ask his assistant how many people work in the studio alongside him, she tells me, “He has a few assistants, but Monsieur Alaïa is the studio; the studio is Monsieur Alaïa.”

His dedication and passion is tangible in the clothes. The exquisite feeling of his clothes is something so special that almost no woman is immune, be it editors or designers, stylists or buyers. “This is what it is all about for me,” he says. “I want women to feel great. When I am making these pieces, I am thinking about all women. It is not one woman, it is every woman. I want them to feel good. It is about all women, young, old, everyone. You see, you are my customer. Maybe you will buy only a few pieces now, but as you get older and can afford more I’m sure I will dress you more,” he says with a huge mischievous grin. It is this sophisticated charm that has cultivated a group of collectors – from Naomi Campbell to Stephanie Seymour to Carla Sozzani and i-D’s fashion director Charlotte Stockdale – that form something between a cult and a family for him. Alaïa has relinquished many of his hobbies these days: “I travel from my desk to my television now. I don’t have much time these days.” But he loves to read and he loves to watch old cabaret and silent movies. With a gleam in his eye, he confesses, “I wanted to be an actor, a singer, a dancer, if I hadn’t been a designer. That is if cooking didn’t work out.” His main pastime these days though is being a collector himself.

Alaïa has a huge collection of Balenciaga, Margiela, Vionnet and Comme des Garçons. “I don’t want to leave anyone out. Rei Kawakubo is the only one I will mention as a favourite designer because she is a great woman, she stands apart and I love her work.” He also collects a lot of design pieces: Martin Szekely, the Bouroullec Brothers, Pierre Charpin, and Marc Newson, who is also one of his best friends.

For Alaïa, there is an implicit link between art and its creator. Just as many of his own collectors have become long-term friends, so he has befriended many of the artists whose work he collects. “Some people don’t like to meet the artists who make the work they like because they are often disappointed,” he says, “but I like to meet the artists who I collect, who make the work I love. I always like the artists whose work I like. I accept the person exactly as they are. If I like their work, I like them.” He hopes to eventually turn his Rue De Moussy store – that currently functions as his atelier, showroom and home – into the Alaïa Foundation, to house his archive as well as everything he has collected from other designers and artists.

The weekend after Paris fashion week finished, with very little fanfare, Monsieur Alaïa opened his second ever store. The new space is a palatial three-storey mansion in Paris’s Golden Triangle, right next to Balenciaga, Prada, Céline and Chanel. There are no shop windows, which Monsieur Alaïa says affords him a certain freedom, but there are high ceilings and light airy spaces looking out onto a central courtyard. This gives each colour or material room to breath, and highlights accessories and dresses on display like sculptures. So, why now, over 30 years after he opened his only other store? “It was simply a question of finding the right space, which we finally did,” he replies, nonplussed.

The “we” in this conversation refers to the owner of 10 Corso Como, Carla Sozzani, his great friend and something of a business partner, who he says played a big part in making this store happen. “She is like my sister. Our relationship is so special. She has so much energy. She is always positive and optimistic. She is also extremely elegant. She is strong and soft at the same time. I have never met anyone like her. And I have met everyone, every editor, every stylist but I have never met anyone like her. Really never.”

This link between Alaïa and his work knows no bounds and it is something you understand once you meet him. His warmth stems from his upbringing in Tunisia where he says he was always surrounded by family and friends, eating together, discussing. “There is luxury, and there is luxury,” he says.

“For some, luxury means having lots of money and a huge car, but to me that means nothing. What is all that without a good plate of food? For me, luxury is being able to do exactly what you want every day, to have a great plate of spaghetti with great friends and family, or a delicious mozzarella, tomato and basil salad.”

Woody Allen once said there are only four things that matter in life: health, education, people and money. Alaïa agrees. “Of course having your health is important,” he confirms. “You can be poor but if you have your health you can still work. To be honest, even if you have no education you can still work, and you can still eat a delicious sandwich. But with all the money in the world – you can’t buy a simple plate of pasta that I cook in my kitchen. Health and friends are the two things that are most important – the rest means nothing.”

Credits

Text Anna Laub

Portraits Sølve Sundsbø

Studio Photography Gilles Bensimon

Fashion Director Charlotte Stockdale

Photography assistance Myro Wulff, Hannah Burton, Moritz Kerkmann, Mathieu Boutang

Retouching Digital Light Ltd

Production Therese Lundstrom at Brachfeld Paris