I grew up in Hayes, Middlesex. Our house was a ten-minute walk to Southall Broadway, which, if you’re Asian, basically means that you lived by Little India (it’s par for the course that there’s a shop named that on the high street). Southall was where my mum grew up, and was home to hundreds of Indian immigrants in the 80s who settled there after coming to the UK. The majority of those were Punjabi, like me, and it was the place that first and second generation immigrants felt safe.

The psychology of a lot of first and second gen Asians was about creating a haven – not only to create strong ties with a community, but to create a space which was safe. If you didn’t feel welcome on the high street, you were in Southall. If you didn’t want to be called a Paki when shopping in your sari, why would you go anywhere but there? My grandparents subscribed to a simple ideology. Indians weren’t visible in the mainstream and that was fine – if we wanted to have a voice, it was best heard in Punjabi, with our community. It was best to keep your mouth shut.

Then, the third generation found their voice. While I had grown up in a house that played old Bollywood tracks, heard dhol players and Bhangra at weddings and knew classic Hindi songs like Mera Long Gawacha from Sunrise Radio, outside the house, things were changing.

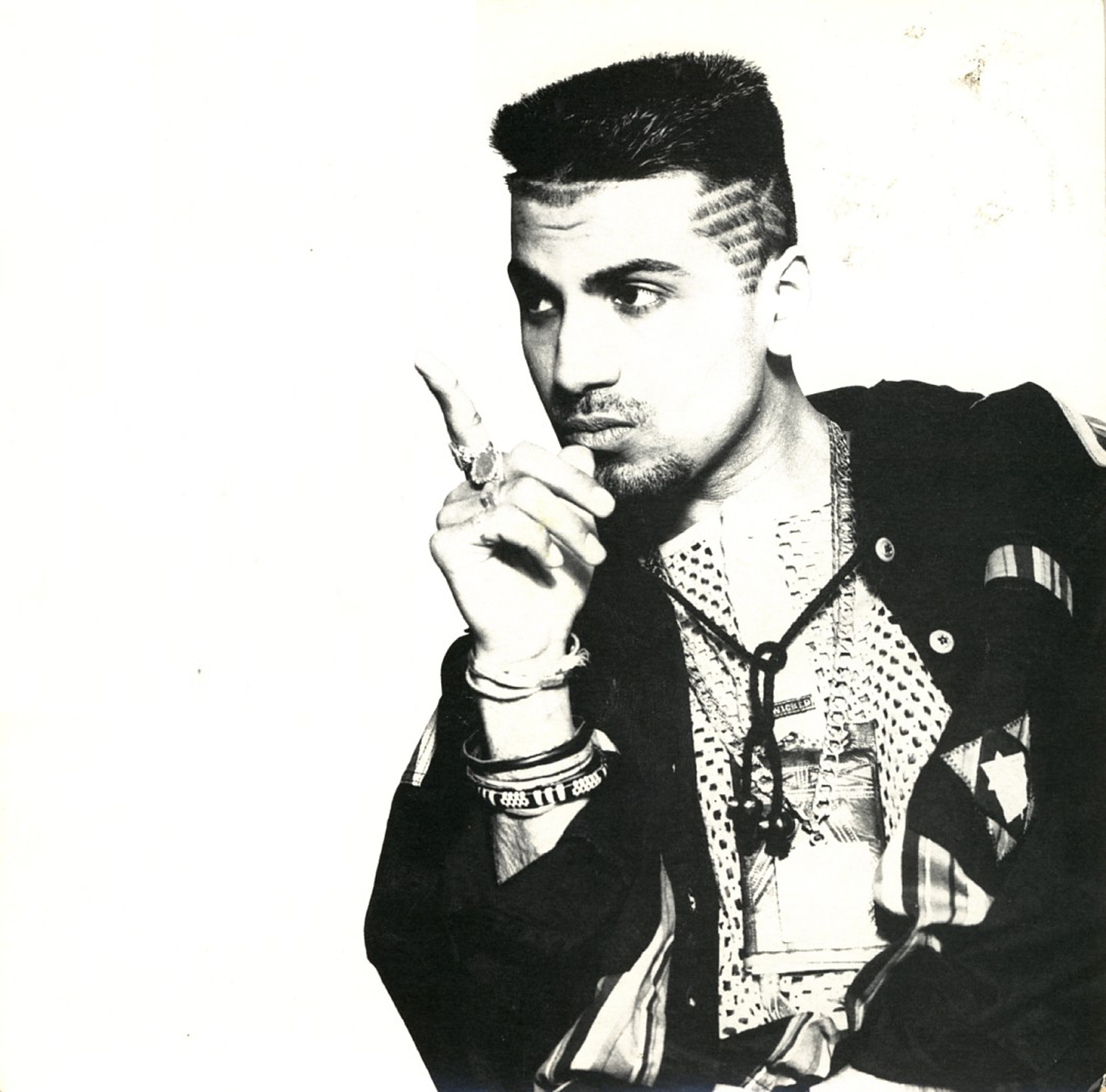

Suddenly, as a teenager, I found myself running down Southall High Street to buy Apache Indian and Bally Sagoo tapes, at the beginning of a new (brown) cultural capital in music. The embarrassment that I had normalised about being a neeky brown girl from an uncool culture was dissipating. Things were changing and it went beyond Cornershop in the Top 10 and Gwen Stefani wearing a bindi. It was my cousins talking about club night Bombay Jungle, it was Bhangra being blared out of cars (their dads BMW’s), it was about ownership of a sound.

This was all thanks to a range of complex factors, but to generalise wildly, it came down to three things. Perhaps most obviously, it was an anger for a generation of Asians who felt culturally marginalised, it was because of access to new technologies that made our music accessible, and, well…it was because of Apache Indian.

I was actually just a bit too young for the full-blown Apache Indian hype but I know it was a moment. It was the pop music version of your mum calling you in the living room because a brown person was on TV – it was visible. Apache Indian’s 93 album No Reservations was exactly that. It had songs like Chok There sung in Punjabi, songs about arranged marriages, and it appropriated Rastafari culture. We were always going to love him (he sung about our home city Jalandhar!) and even English people liked him – and that fact alone, for us, was amazing.

The 90s also saw luminaries of the Brit Asian scene, like Bally Sagoo (who remixed the aforementioned Mera Long Gawacha, to my mum’s horror) and the release of iconic albums like By Public Demand by B21. These artists were in no way as popular as Apache, but made the point that something had shifted. Now we were playing bhangra in full view, in classrooms, in shops, on the 207 to Ealing, and we didn’t feel any shame about it. It was the opposite tactic to keeping out heads down hoping out classmates wouldn’t see us in a lengha, or hear Asian music playing in a car; it was our protest music.

What followed was sampling of Bollywood and Bhangra tracks into songs that got mainstream play. It was Mundian To Bach Ke, it was Gwen in a bindi, it was Truth Hurts sampling Thoda Resham Lagta Hai, it was Goodness Gracious Me.

I was too young for (and prohibited from) iconic Brit Asian nights like Bombay Jungle in West London, or going out on the infamous Bath Road, but by the late 90s fetishisation of Indian culture opened up Brit Asian music, so by the time I was an older teenager in the 00s, there was already a culture. We always knew that our Bhangra was great, and now everyone else knew it, too.

By the time I was 17, the tide had turned and Hip Hop remix culture (Bhangra version of 50 Cent’s In Da Club, anyone?) had infiltrated Bhangra thanks to Juggy D and Rishi Rish. That was a period of filling up my Windows Media Player with songs I never knew the names of but were being played out at weddings, diwali parties, melas, and the 607. These tracks paved the way for radio stations like BBC’s Asian Network (and was the reason thousands of people campaigned it from closure in 2010).

Thankfully, now the Brit Asian scene is brazen and uncompromising – in a way that my grandparents would have never thought possible. Our music had a moment that made our experience of the UK feel more like home, especially for people like me, who always felt outside of any kind of cool culture.

Now, third-generation people my age can reappropriate our own culture, or, just have a range of platforms that they can enjoy it on. We’ve learned that we’re lucky to have an in-gang that exists as an addition to the mainstream. We can champion Grime, Hip Hop and Rap while also celebrating that Babydoll and Lovely are the Hindi songs of the year. The legacy of Asian soundsystem culture counts for a lot, from making brown girls like me feel cool in school, to giving a generation confidence about an identity that had been ignored. We were telling the world we were here, and we weren’t going anywhere.

Credits

Text Kieran Yates