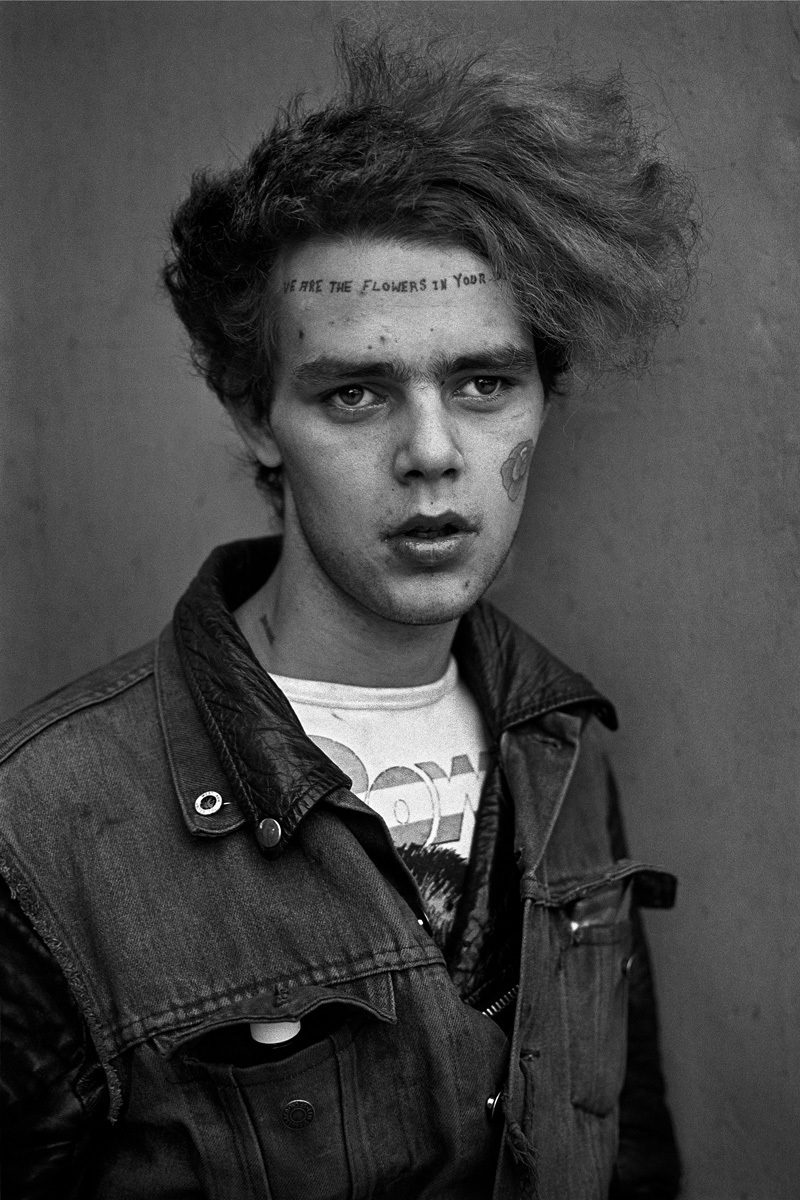

Few images are more strikingly perfect than Derek Ridgers’ two shots of Tuinol Barry, that iconic punk, his forehead emblazoned with a tattoo of a Sex Pistols lyric: “We are the flowers in your dustbin.” In one, Derek captures him shaven headed with big vulnerable eyes, pouting lips, and pierced nose. His expression a mixture of defiance and resignation; the reluctant nihilist. A few years later, he shot him again, his hair grown out and wildly combed across his head, still revealing that provocative, accusatory tattoo, a Bowie tee just visible through his denim jacket.

The two images — shot only a few years apart — document a volatile time in British culture, a dramatic and violent rebirth of the underground; on the streets the flowers in the dustbin were blooming in cracks more used to weeds. Derek’s photos chart a time when culture felt vital enough, when youth felt angry enough, to get such a refusal of society tattooed across their foreheads forever. There’s Tuinol Barry, across the years but forever the flower in your dustbin.

These photos form just a small segment of a new exhibition at London’s Beetle + Huxley Gallery, titled An Ideal For Living, a survey of the works of over 20 photographers, spread over 80 years, documenting the changing class, culture, and identity of Britain. Documenting it as it morphed from the interwar years, the last glorious hurrah of the class system and Empire, to the grey and cold austerity years of the 50s, the dramatic cultural rebirth of the swinging 60s, the turbulent 70s, the rise of Thatcher, the great social cleansings and divides and ruptures of the 80s, the ascent of Blairism and the new cuddly neo-liberalism of New Labour and chummy appropriation of the laddish working class of Britpop in the late 90s. The still-relevant echoes of all these things we find today. Quite a span of time, attitudes, poses, and politics to chart.

The exhibition’s curator, Flora La Thangue, explains how “the photographs in the exhibition show that class has, and always will be, a performance.” This is evident in the exhibition’s earliest images, works by Bill Brandt and E.O. Hoppé; pictures of parlor maids, and a schoolboy stacked high with luggage waiting for a train at Paddington. They’re both examples of a social divide in Edwardian Britain; a Britain where you knew your place. But it’s unreal too, a performance. “Brandt’s photograph of the parlor maids was entirely staged in his own uncle’s house,” Flora clarifies. Hoppé’s schoolboy, too, feels staged, too perfect, too aware.

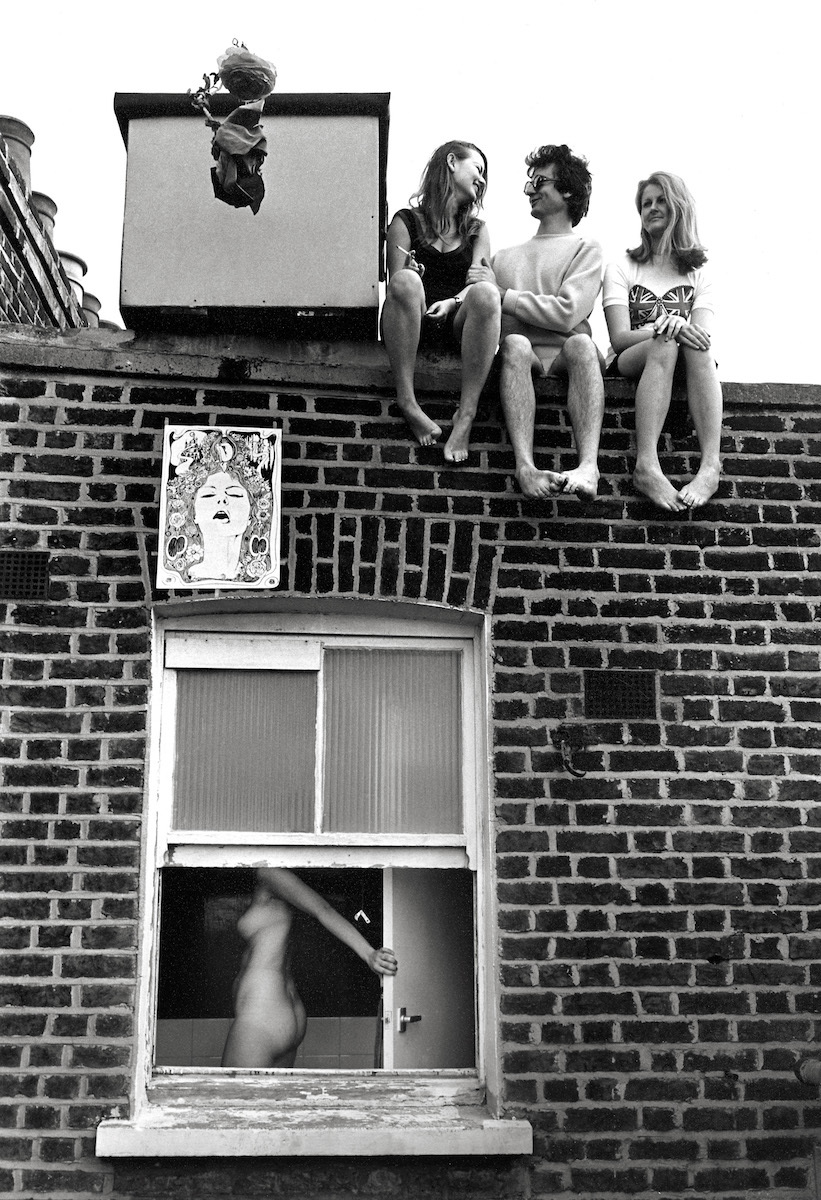

So these images are performed for the camera, but also, they document class as a performance, the rigid adherence to the rituals and codes of the tribe. “From the 30s onwards, photographers have sought to document the ways in which groups brought together by class, religion, age, or ethnicity have built communal identities,” Flora says. “The theatricality of class identity can be seen as clearly in Bill Brandt’s photographs of parlor maids from the 30s as in Colin Jones’ images of working class communities in the North of England and in Frank Habicht’s images of the Swinging 60s.”

And it’s in the 60s that the exhibition swings into life. There are images of Teds, rebellious and quiffed, who preceded and laid the ground for the youthquake of the 60s. But it’s in the 60s themselves, when the self-realized class identities become frayed and less visible, more flexible and more elastic, that the documentarians’ task becomes more intriguing. As the imagination expands, so does the possibility of the performance.

There’s an image, captured by Frank Habicht in the early 60s, of two girls, styled out in Quant-esque miniskirts, loafers, exquisite knitwear, flowerpower headbands. They’re speaking to a classic banker of the old school type — full Savile Row suit and bowler hat, round specs, rolled up umbrella doubling up as a walking stick. He’s out on the streets of the City, the girls asking him the time, an uneasy clash of old and new worlds, yet there’s no friction; a laugh escapes from the banker’s mustache-rimmed mouth, as if he’s in on the whole glorious, ridiculous spectacle. There’s an uneasy ghost at the feast in the background though, not in on the joke, a flatcapped and work-jacketed 50s relic staring down the lens in the distance. He could’ve been launched in from a different image, he’s conspicuously not part of the conversation. The world, you imagine, will go on to be the same for the banker. There’s a new world opening for the young. But there soon won’t be much of a place left for that gruff specter of an old working class. Those girls though, performing their new-found liberation, are conscious harbingers of a new mode of being, a joyful crash of light into an old grey world.

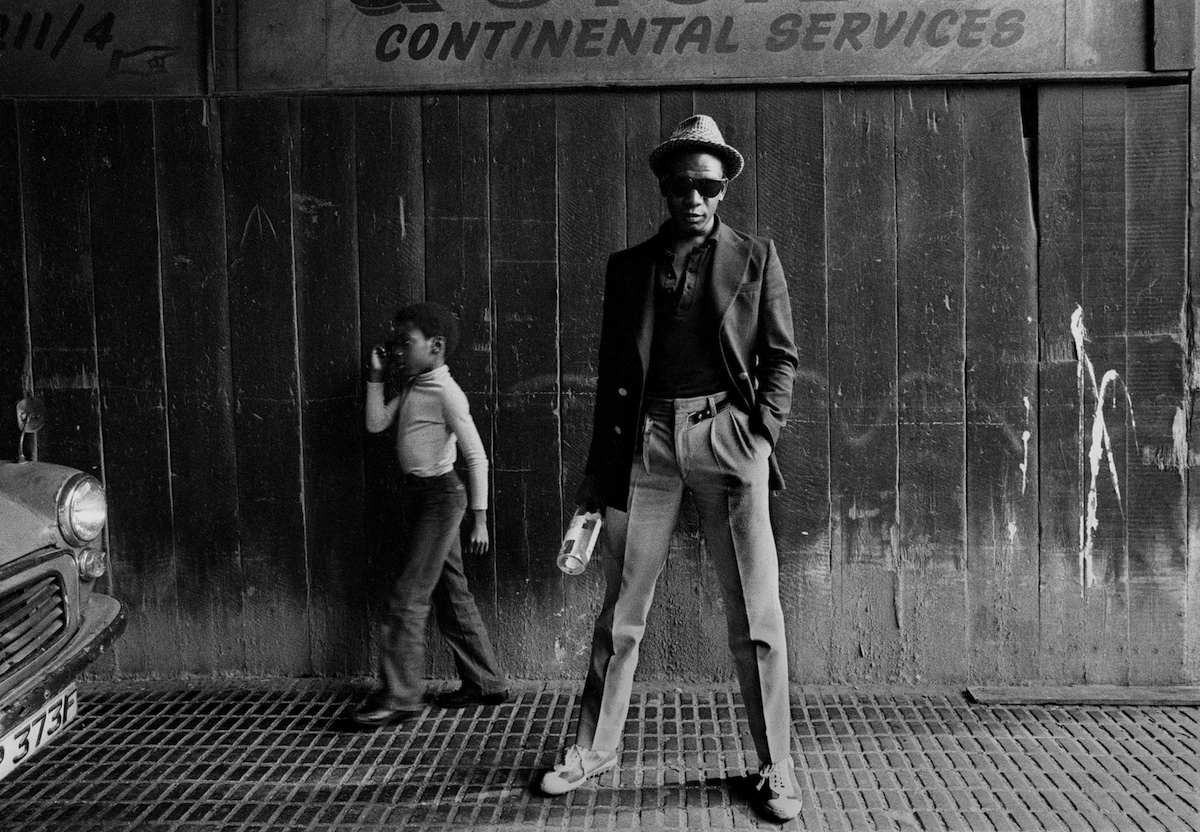

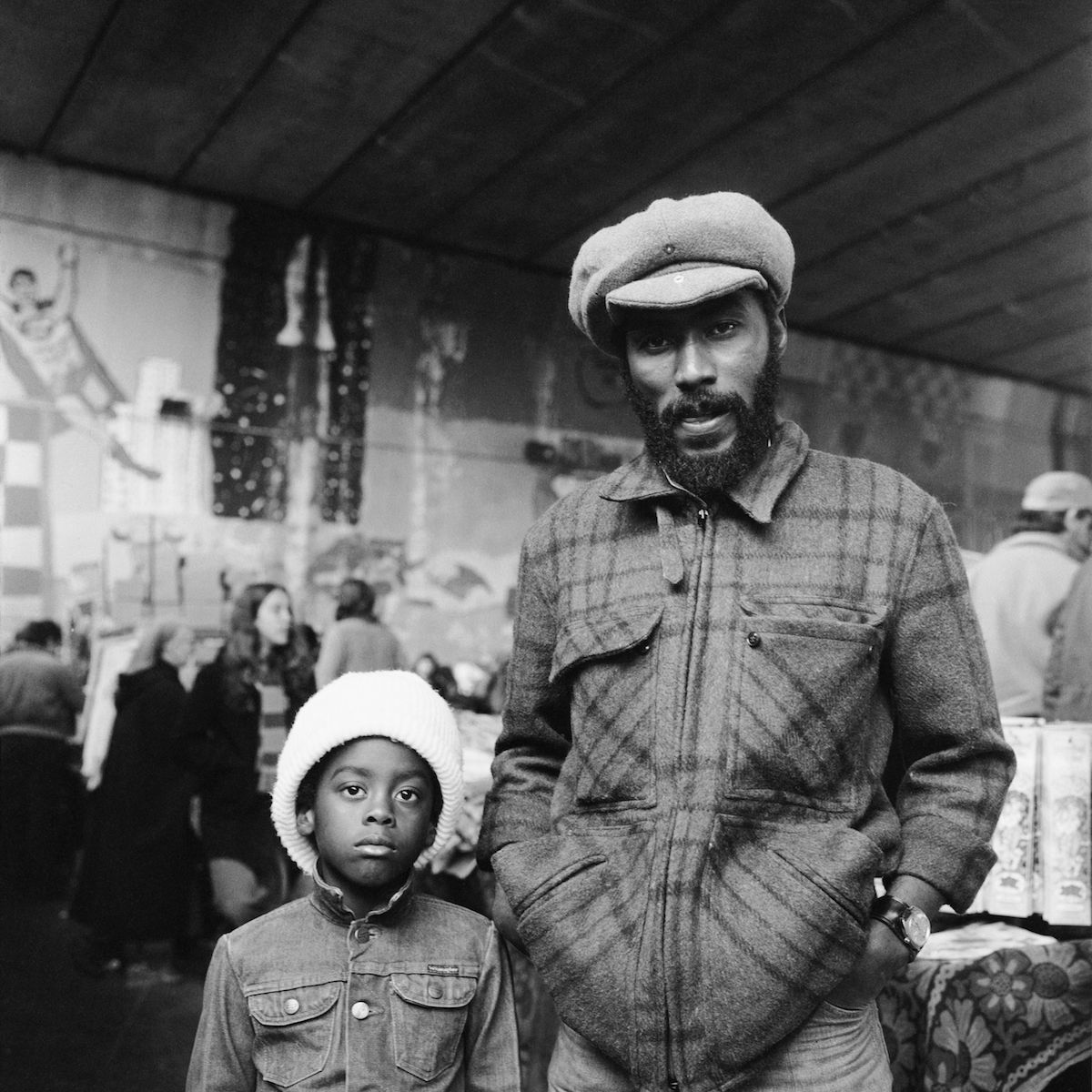

The 60s were a sort of childhood arcadia of class and culture in the country at large, a time were coexisting tribes slipped by each other without resistance, an era brought back down with a crash by the time the 70s rolled around. Or rather, reality had caught up with the dream. The 70s became a time of social unrest, that manifested itself at the end of the decade in punk, the nihilistic response of a generation who felt like they were the flowers in the dustbin of British society. Immigration from Britain’s old colonies had brought a new culture, which manifested itself first, in the 60s, as mods, a more holistic merging of two cultures’ class identities, and then skins, a violent monocultural reaction to a changing culture and class identity.

“The urge to rebel becomes, ironically, a common thread that runs through many of the photographs in the exhibition,” Flora suggests. Rebellion is of course at the heart of youth culture, a reaction to the world our parents created. But there are two caveats; one, Jürgen Schadeberg’s images of the rich and rarefied world of the students of Cambridge University, the other Charlie Philipp’s document of Black British life at the time. The rebels, those being rebelled against, those striving simply to find a place — An Ideal For Living is a quest as much as it could be an instruction. Changing patterns of immigration’s impact on the city and its inhabitants drums out a beat throughout the photos. Mahtab Hassan’s image of a girl in a red hijab, gliding past a paint-peeling gate in 2013, in what could be any identikit area of any identikit city, stands in uneasy counterpoint to Syd Shelton’s image of Bagga, in Hackney, in 1979, equally impeccably dressed as a girl, in full mod uniform. The questions posed here haven’t gone away. They’re as relevant to an older, whiter working class, as to newer, first- and second-generation immigrants.

James Morris’s landscapes of Wales, post-industry, capture the resonance of the changing class structures writ in the earth. Peter Dench’s photos of Epsom capture those who’ve preserved a bit of the old world rites and rituals in a sea of G&T and Union Jacks. It’s a photographic debt owed, of course, to Martin Parr, who has spent a career capturing those rites and rituals, the character of Britain’s working class life faded but not quite disappeared.

Class changes, identity morphs, but some things are constant if not immutable. The success of An Ideal For Living is picking up the echoes across the ages; the impacts of waves of immigration, changing economies, shifting counter cultures, it picks at those moments and seems to say, the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Credits

Text Felix Petty

Images courtesy of Beetles + Huxley