On January 7, 1978, the Iranian Revolution began. By 1979, the country had become an Islamic republic, overthrowing the Pahlavi dynasty who had ruled Iran for half a century. Before that, throughout the 70s, the Iranian monarchy heavily invested in the arts with a desire to Westernize the country; from the late 60s onwards, European disco and pop began to infiltrate the middle eastern country and influence the more traditional forms of Iranian music. “In the 70s Iran was pumping a lot of money into music, and financially, they were doing quite well as a country,” Kasra V explains. Ksara moved to the UK several years ago and is now an NTS Radio host. His new EP The Window explores the music of his birthplace, specifically the South Iranian musical style, Bandari.

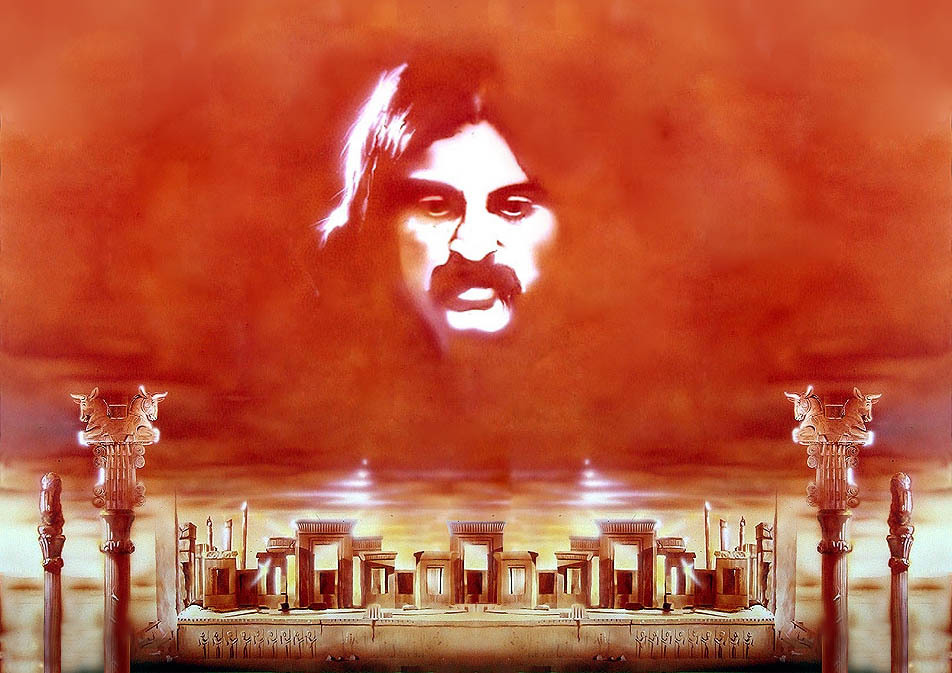

Iran, before the Islamic Revolution, was full of cultural delights that mixed east and west together. In the 70s artists like Farrokhzad Fereydoun — an openly gay musician, political scientist, and TV host — and Kourosh Yaghmaei — whose works were compiled five years ago by Eglo on Now Again Records — were enjoying mainstream success in the country. Artists like Shohreh and Ebi were making “big records with big orchestras,” Kasra explains, fueling a vibrant music culture that mixed psychedelic pop, folk, and middle-eastern rock. Some of the biggest artists of the age, Googoosh, Dariush, and Farhad Mehrad were creating songs full of soaring emotion. “Some of them were almost too emotional,” Kasra laughs. “They peak too much, some of them were almost a whole song of peaking.” Some were political, such as Farhad’s track, “Jomeh.”But mostly they echoed what Western musicians were writing about at the time: love, loss, and simply having a good time.

After the revolution, contemporary music, art, and performance were restricted, curtailed under laws brought in to make the country more Islamic, in line with the new regime’s beliefs. Widespread censorship was enforced, there was a desire to rid the country of Western influence. A number of artists either fled the country to continue in their careers, or remained in Iran and adjusted to a new life. Googoosh, one of Iran’s biggest pop stars, has not performed in her home country since the revolution. With the exception of vocalist Shiva Soroush, who performed in Tehran in both 2013 and 2015, laws allow female singers to appear only in a group and only as background performers for male soloists.

Some of these restrictions towards art and music remain in place today, but contemporary music scenes still exist in Iran in one way or another. There is a more than healthy group of young electronic musicians and producers making great music, and while ‘club culture’ as we know it is non-existent in Iran — alcohol is illegal and live shows are difficult to arrange — a nightlife scene can be found there, it’s just a little tougher to discover. “It’s not allowed to but it’s going on,” Kasra says, of his experiences of clubbing in Tehran. “It’s like everywhere in the world. People need to dance and have a good time, people need to let some steam off.”

There’s a DIY attitude to electronic music within Iran, which is vital if you want to get your music heard while falling within the guidelines they country enforces. The few venues that exist are unwilling to take the risk of hosting actual club nights so house parties become their replacement. “Everything that happens, happens within closed circles. Parties were always in people’s houses,” Kasra explains. “But some of those parties were bigger than clubs here. I’ve been to parties of 400 plus people, all organized through text message.”

I ask how these parties were allowed to continue? “They aren’t,” Kasra replies. “It’s a big city, but it really depends on where the party is. It’s not like in London where if you have your television on too loud your neighbor goes crazy, people have a lot of space in Tehran. Most of the time, if you knew your neighbors and they were nice, you could get away with it.”

All forms of official recorded music and live performance need to be approved by the Ministry of Culture but in recent years, and supported by the current, more liberal administration, these restrictions are beginning to loosen. “I’ve heard that recently, some people have been trying to get away with doing more ambient and techno stuff, as it just doesn’t have any words,” Kasra explains. While electronic music is far from exempt from censorship, it has an easier ride than other genres in the country.

These eased restrictions are the result of electronic music being — fort the most part — instrumental. Music without lyrics is much more likely to be approved by the Ministry of Culture, and as such electronic music bleeds into everyday life more-so than other genres do. “Almost everybody has satellite TVs,” Kasra explains. “National Geographic always used to have Kraftwerk and Vangelis on the soundtracks to their programs; ‘Oxygen’ by Jean Michel Jarre was the theme tune for the big technology show in the country. I was listening to that stuff without really knowing I was always listening to it.”

In recent years Iranian artists have welcomed an increased interest and a greater international platform for their music. Producers such as Sote and Siavash Amini are pushing a much more left-field and experimental sound within Iranian electronica, whilst the recently released, feature-length documentary, Raving Iran, showed another side of the country. In very brief detail, the story follows two Iranian DJs from Tehran as they head to Switzerland’s Lethargy Festival to try and make their name within the electronic music world. While it drew attention to the problems that electronic musicians face within the country, it painted a picture of a genre which has been all but stifled out of existence within Iran, which isn’t the full story.

While Kasra experienced painfully slow internet during his time in Iran — “it would take like eight or nine hours to download a 100mb file,” he says — websites like Beatport and Resident Advisor are available within the country, and the pirate tape culture of old has made way for mp3s like it has across the world.

Incredible music is being created in Iran and thankfully, it is beginning to enjoy much wider success. It will take time, like any emerging scene does, but as restrictions on music become more liberal, people will continue to experiment and take it into uncharted territory. It’s DIY, but it’s dedicated.

Credits

Text Jack Needham