Whether you copped from a skate shop or coughed up 10 grand on eBay, there’s a pretty good chance you’re wearing a pair of sneakers right now. Despite this shared , it doesn’t take a sneakerhead to see the difference between Keds and Kanye West. But that’s exactly what The Rise of Sneaker Culture — a new nationally touring exhibition which makes its debut at the Brooklyn Museum today — explores. Before we battle the crowd to catch a glimpse of Run DMC’s very own Adidas, we caught up with curator Elizabeth Semmelhack to learn more about the sneaker’s rich sociocultural history.

Tell us about the sneaker’s origins.

Many of us think of a sneaker as something that, historically, hasn’t had much importance in terms of status. But the earliest sneakers were actually first embraced by an emerging middle class who used dress to express the privilege of their newfound time to play. One of the threads that runs through the exhibition is technological innovations that have driven the history of sneakers. Today, rubber itself is so ubiquitous, but in the first half of the 19th century, it was hard to come by. So even though early sneakers look relatively humble to the modern eye, they were technologically advanced and pretty expensive status symbols.

When did the turning point come?

Because so much of New York’s working class population was crammed into urban living environments inhospitable to fresh air and exercise, Central and Prospect Parks were created, which–coupled with colonialization’s exploitative cultivating practices that flooded the market with rubber–lead to sneakers becoming less expensive and embraced by a wider population. Although WWI created remarkable devastation, science helped so many injured bodies survive that the culture of the interwar period became focused on physical perfection. This was partly driven by Hollywood and the media, but also by very unsettling concepts of racial superiority; Nazis, for example, encouraged their citizens to exercise in service of the state. So as exercise became an increasing political idea and footwear production advances, sneakers became democratized and brought into the wardrobe of millions of people.

When and why did sneakers start becoming flashier?

After WWII, the sneaker was so inexpensive that it became the footwear of childhood. The sneaker’s connection to status essentially disappears until the 70s, when Nike co-founder Bill Bowerman brings jogging to the United States and new generations embrace this idea of exercise not in service of the state but for self, which leads them to seek out very high end, technically advanced footwear. Nike very smartly combined this cutting edge, lightweight technology with bright colors that were so eye catching, they start popping up in places like Studio 54. So this idea of casual fashion and athleisure wear becomes pretty important in the 70s.

That’s happening in one demographic, but at the same time, newly televised sports entered into millions of households and had to be eye-catching. Streetball moves that were being done in urban environments like New York City translated perfectly to the professional arena. Basketball stars like Kareem Abdul Jabbar started to get signature shoes, and kids within urban environments began to wear them. These concurrent trends gave rise to the watershed moment of the 80s, when Michael Jordan signed with Nike and Run DMC signed with Adidas, effectively disseminating urban fashion to a much wider audience.

Many of the exhibition’s sneakers are pulled from private collections like Daryl of Run DMC. What are some unexpected gems?

Out of the millions of sneakers created, I think almost every single one of the 150 on view here is quite important in the history of sneaker culture. Some have become so ubiquitous, people don’t realize it hasn’t always been that way. The Stan Smith is a great example: the model started out as a Hele, a famous French tennis player. When Adidas wanted to branch out into the American market, they looked for an American to endorse the sneaker and reached out to Stan Smith. For a very brief time, Adidas produced the Hele Stan Smith with both players names on it, and I have one of those models.

We’ve also got original Converse All Stars from 1917, a pair of running shoes from the 1860s, original Air Force Ones, original Air Jordans 1 – 23, as well as designer models from Christian Louboutin and Pierre Hardy. I tried to make sure every single one was heavy hitting and sneakerheads will say ‘damn straight she should have had all of these!’

Artist collaborations seem to be pretty popular today, why do you think that is?

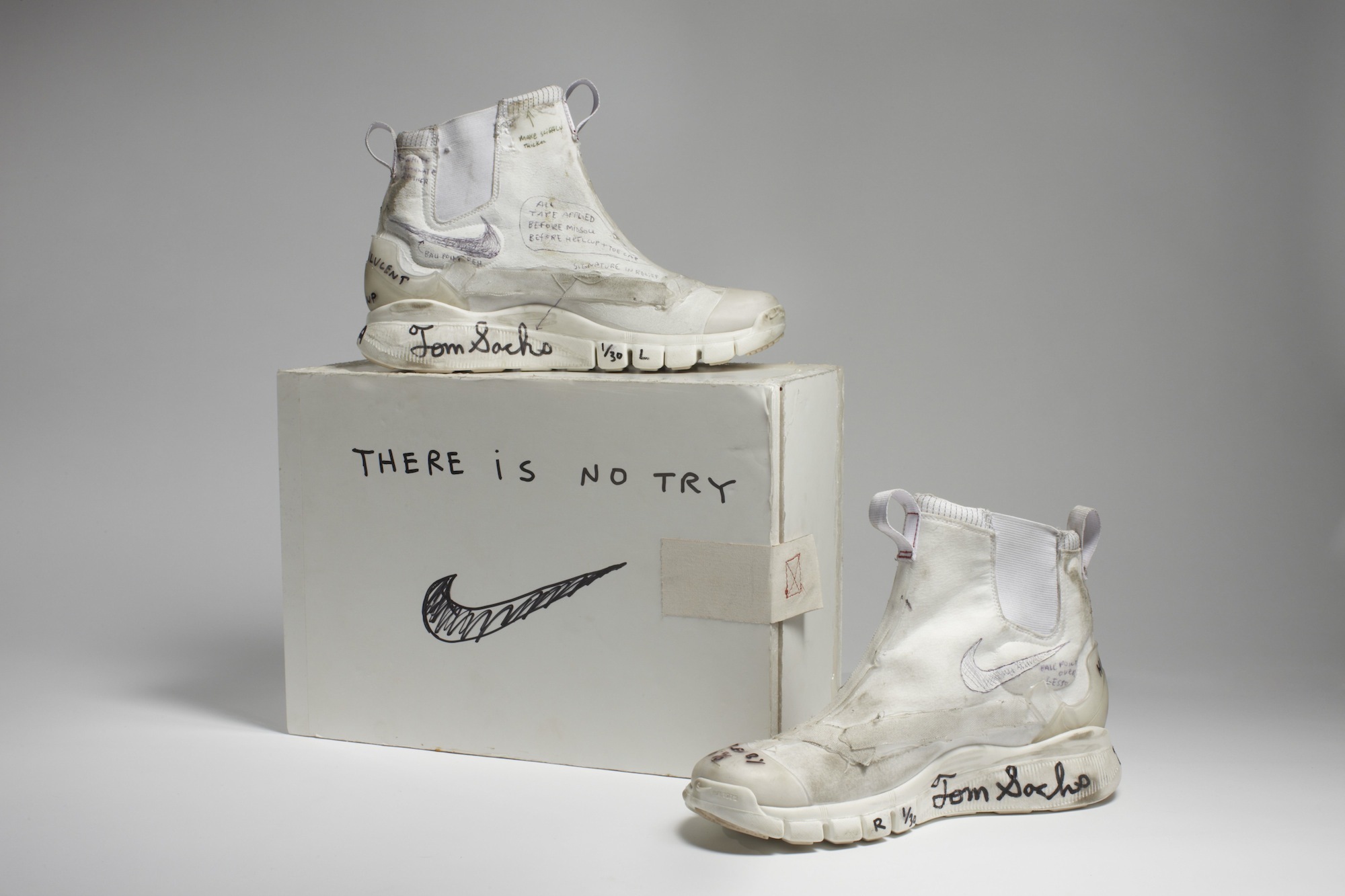

The whole idea of collaboration really takes off in the early 00s. We have both Jeremy Scott’s and Yohji Yamamoto’s first collaborations with Adidas, but as the 2000s progress, visual artists start doing very limited edition runs. One of the things I’ve always appreciated about Tom Sachs’ work is that he explores the fetishization of branding and when mass production eliminates the maker’s hand completely. So I thought it was interesting that when he collaborated with Nike, he made shoes that retained the artist’s mark.

We’ve spoken a lot about men’s roles in shaping sneaker culture, but not so much about women. What role does gender play in this history?

I purposefully wanted the exhibition to focus on shifts in masculinity, as I don’t feel sneaker culture has fully embraced or enfranchised women. If I did this exhibition in five years from now, I’d be interested to see what changes had happened, but at the moment — while I have a few women’s shoes in the exhibition — I feel it would be disingenuous to suggest that women were allowed to participate at a greater level than they have been.

What do you hope people come away with?

I hope that people come and really appreciate that even though sneakers seem so ubiquitous to our society today, they aren’t created equal. How the sneaker has ended up where it is today is an exceptionally long history that actually is linked to things as varied as innovation, status, gender, economics, and appropriation. It’s a thrillingly complex story and hopefully people see it that way!

Credits

Text Emily Manning

Image Louis Vuitton x Kanye West. Don, 2009. Private Collection. (Photo: Ron Wood. Courtesy American Federation of Arts/Bata Shoe Museum)