The relatively unknown, hushed and largely ignored Peterloo Massacre was a critical event in the conception of widespread radical politics throughout the North of England in the 19th Century and beyond. If you are left scratching your head by the mere mention of Peterloo, don’t worry, you’re far from alone and John Alexander Skelton is here for a history refresher. On 16 August 1819, a peaceful crowd assembled in Manchester to demand the reform of Parliament and was attacked by armed soldiers and yeomanry, leading to many deaths and injuries. The events of that day have been the subject of books, prints and poetry, and now menswear. For John Alexander Skelton, a label in which every seam, stitch and textile is considered, research is everything. From the Mass-Observation Project references of his debut, to the cotton trade and colonialism of his second, the research is rooted in the shifting socio-political landscapes of the north of England. Whilst working in his studio on his second collection, the York-born, London-based designer was told to listen to Melvyn Bragg’s Radio 4 show The Matter of the North by a friend, and the idea for his third collection was born.

“One of the episodes talked about Peterloo and I found it fascinating, I was also struck that I knew nothing about it,” he explains from his Haggerston base. “I wanted to know why such shame was associated with it and I wanted to know more about the people involved.” With his interest piqued and joined by his younger brother Ryan, his creative collaborator and confidante, John immersed himself in the history of the massacre and the radical movements that followed it, from the Chartists to the Suffragettes, before drawing comparisons to Brexit. “That bigoted view that certain people shouldn’t have the vote was extremely similar to to what was happening in the build up to Peterloo and what those workers were fought against,” he reflects.

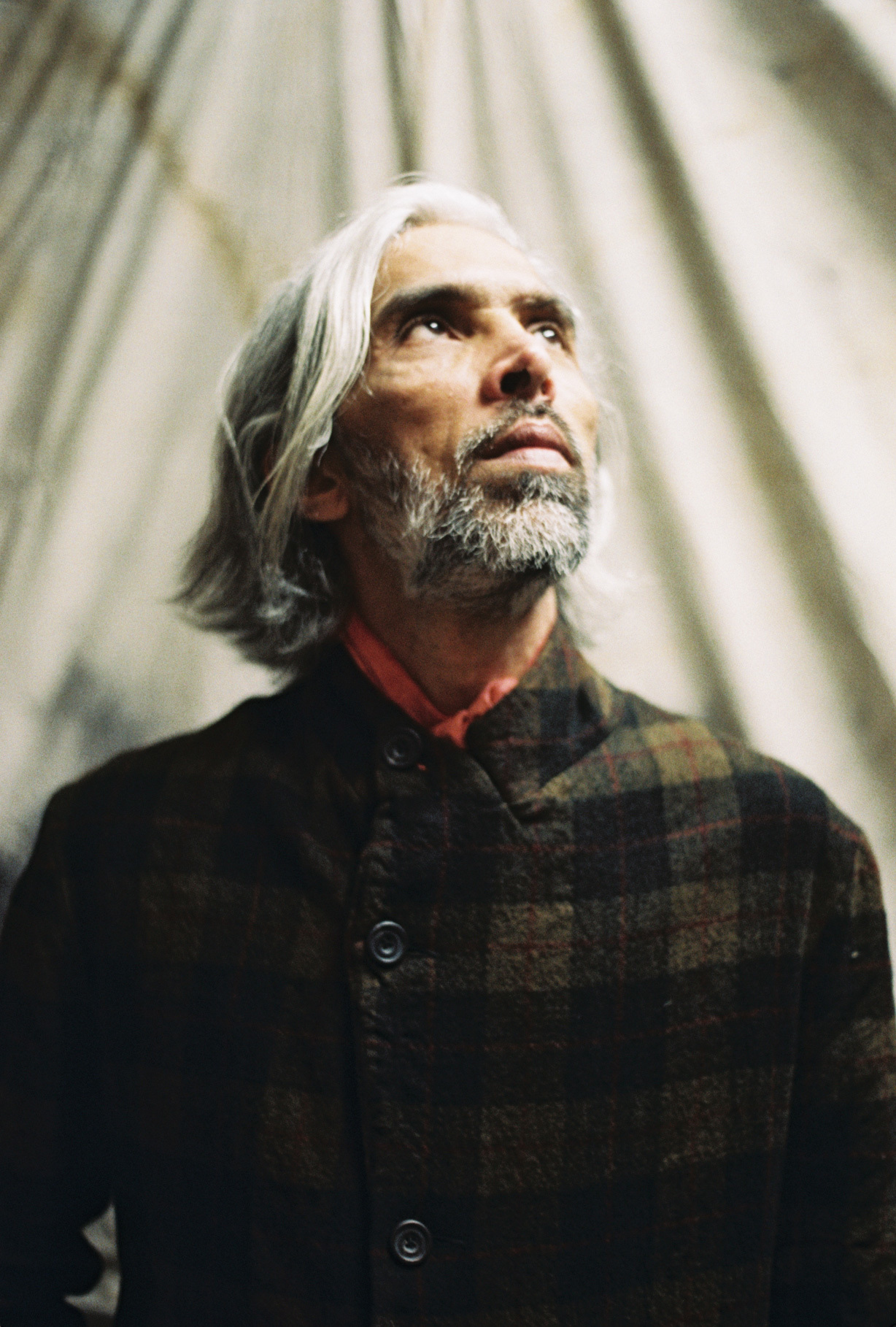

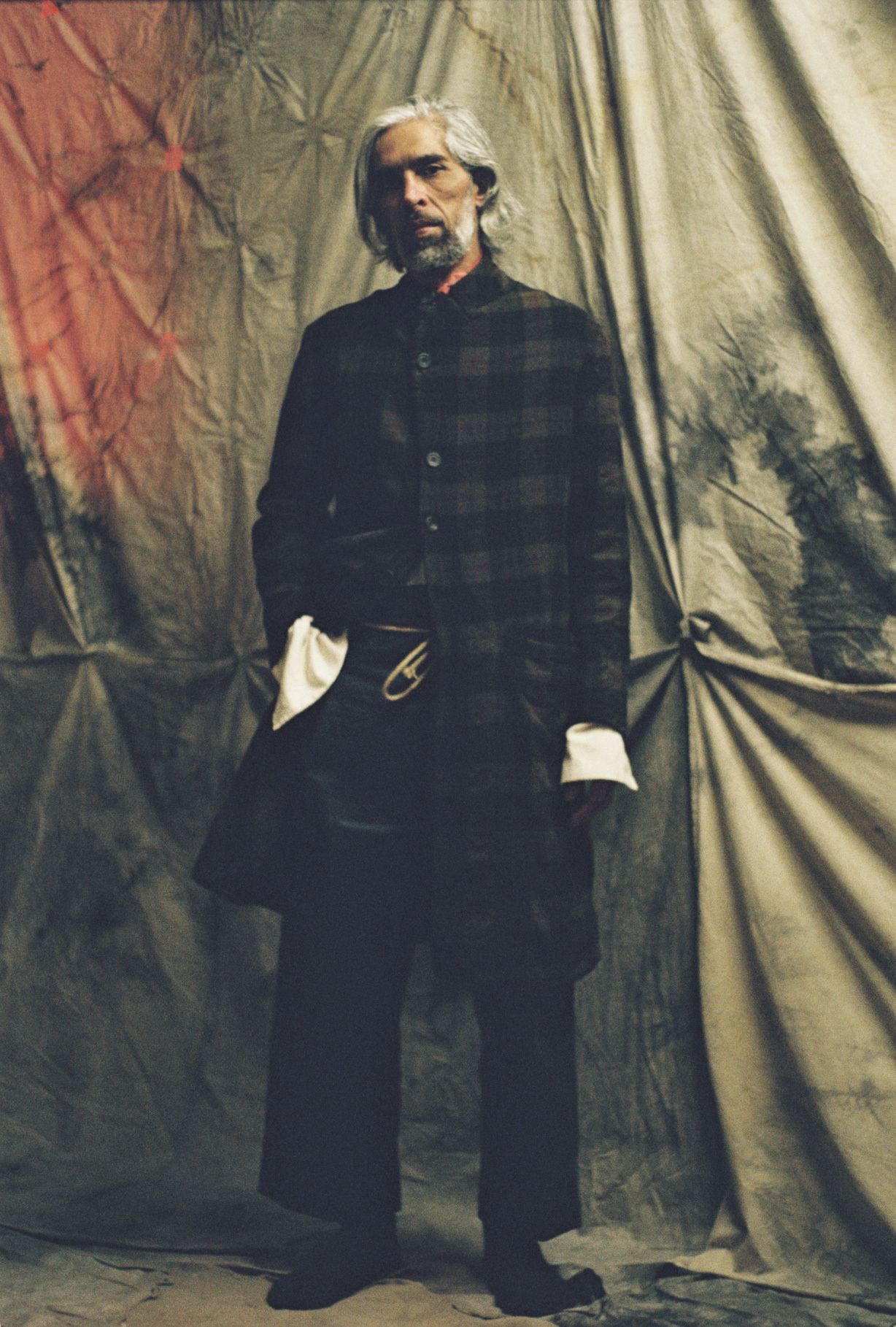

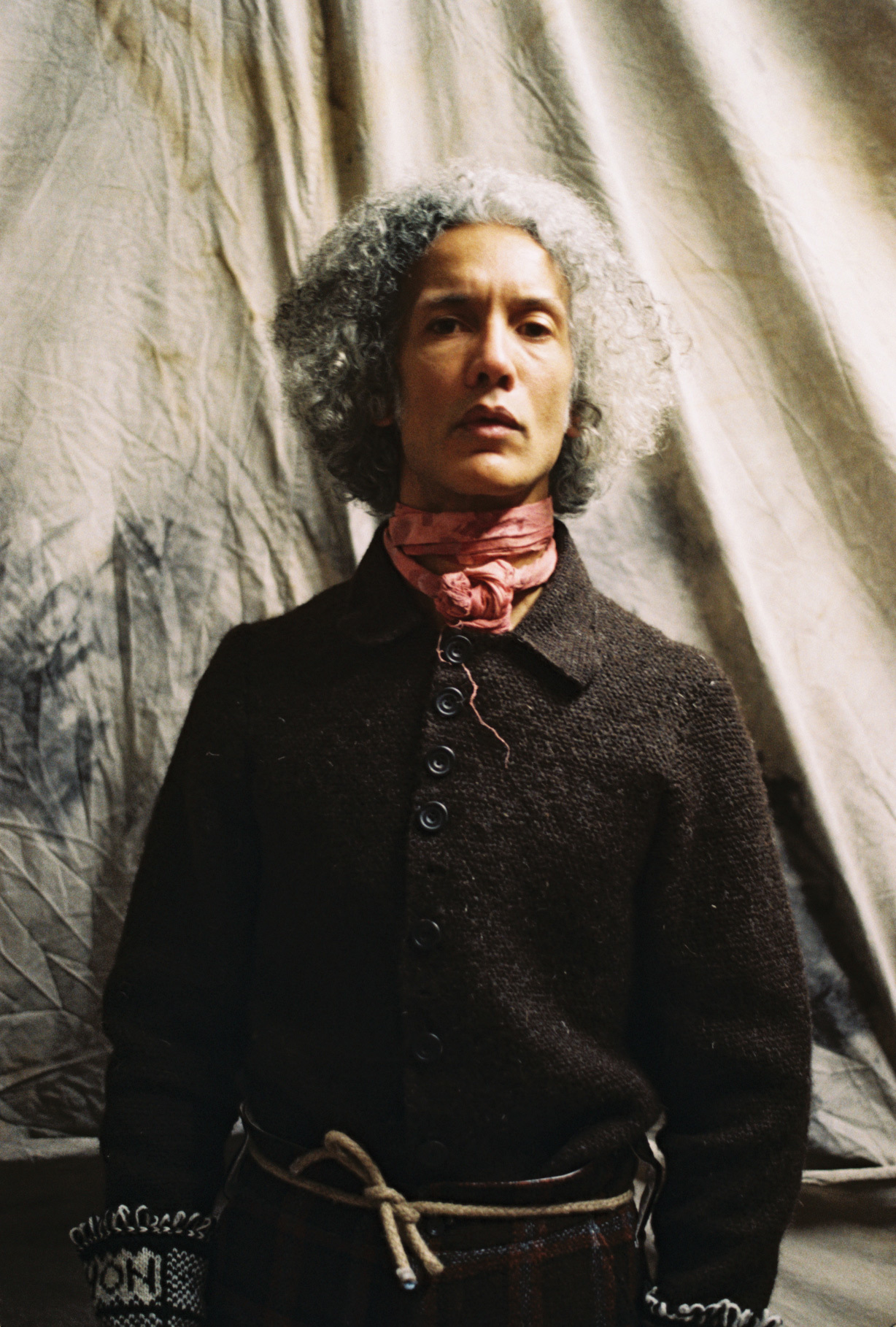

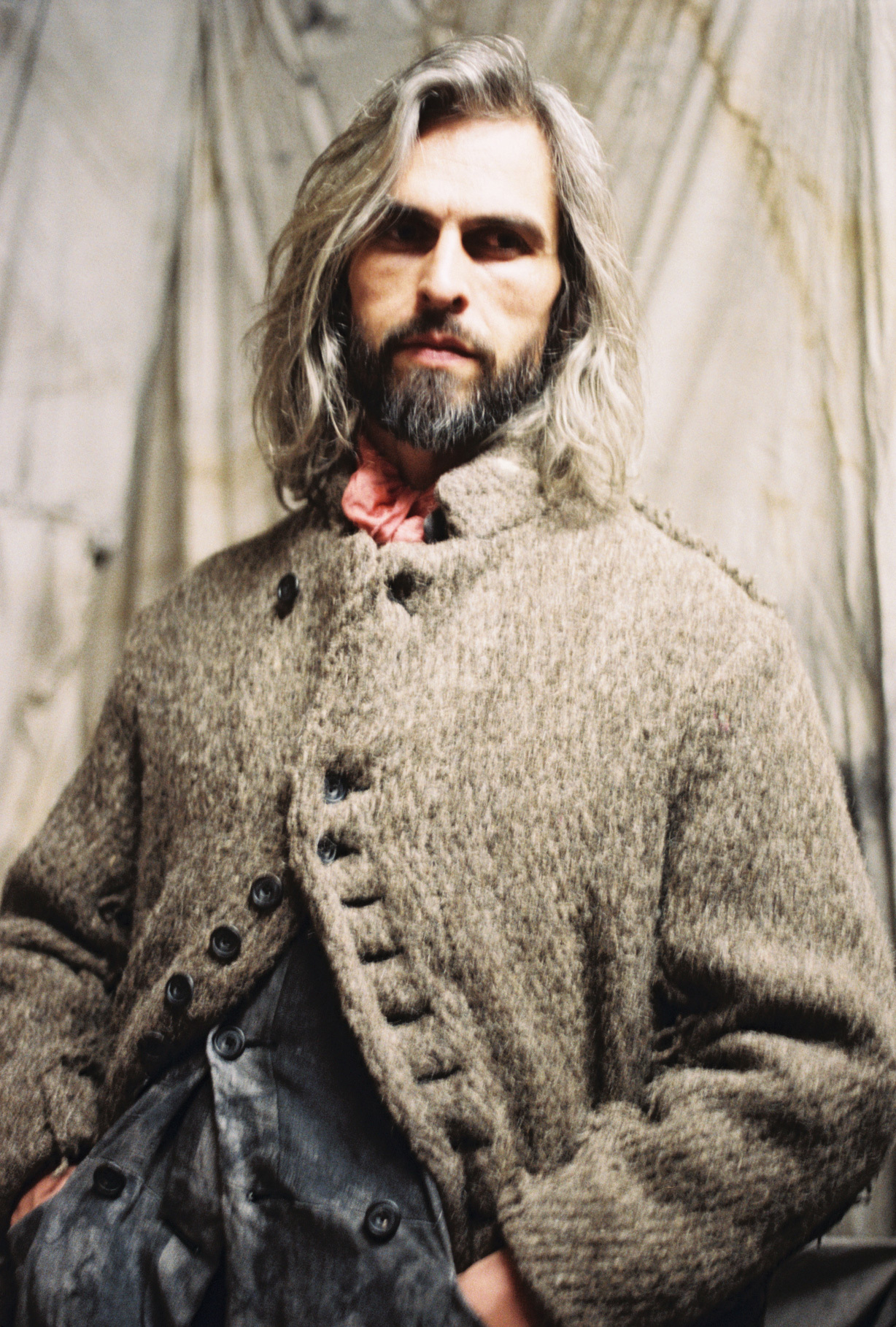

Whilst unpicking the thread linking Peterloo to the political climate of today, it’s really in the tightly stitched existence of the radically political with the often eccentric folkloric practices that captured his imagination here. The result is a particularly rich landscape in which Skelton was able to explore the interactions between everything from the Pace Egg and Mummers plays, to the rebellious acts of Luddites and the secret trade societies that existed before trade unions were legal. As we exclusively follow Ryan’s lens and share the lookbook, John takes us on a tour of the Radical North.

On what drew first him to explore the Peterloo Massacre…

“The collection’s title is a nod to Melvyn Bragg’s Radio 4 show The Matter of the North, The Radical North. One of my friend’s recommended it to me because at the time I was listening to another show of Melvyn’s. One of the episodes talked about the Peterloo Massacre and I found it fascinating. It was the first mass demonstration of workers for workers and voting rights, and it was the first act of police brutality, before the police existed because it was the Yeomanry. The shocking thing was the protesters didn’t expect such a reaction but they did. It was the first time the police, as they were then, went from being guardians to oppressors. It was interesting to reflect on how that shift exists today, how the police can be seen as largely oppressive.

I was particularly struck that I knew very little about it, despite my interest in history. It only touches on Peterloo but it piqued my interest. I wanted to know why such shame was associated with it and I wanted to know more about the people involved. At that time only two percent of the population had the right to vote and there was massive borough mongering element, there would either be two representative to one borough or none, in many of the industrial towns of the North those places had the most wealth and power but the industrialists were the oppressors of the time. It was the first time workers had gathered en-masse to protest and it led to so many different movements, from the Abolition of Slavery to the Suffragettes, the Chartists, even the Labour Party. It’s a massive event that isn’t talked about, it’s not taught in schools and it should be. I wanted to shed some light on it.”

On how this event lead to a plethora of radical movements, from the Chartists to the Suffragettes…

“Peterloo was hugely influential in ordinary people winning the right the vote, led to the rise of the Chartist Movement which led to trade unions, and also resulted in the establishment of the Manchester Guardian newspaper. In the immediate years following the massacre, the general public were quite frightened. It took some time for movements to gain momentum again and the first was the Chartists.”

On the role of folklore and tradition…

“When mass meetings were banned after Peterloo people would only be able to gather during national holidays which were all heavily infused with folkloric tradition, especially for the workers, and led to clothing being significantly political with the use of small items like sashes and ribbons and also the presence of the fustian jacket which was the symbol of the worker at that time. The popular orators of the time, who were not all working class, would wear a fustian jacket to speak specifically. I thought it was interesting how quite insignificant items could become very politically charged and powerful, especially en masse and how they have been adopted by political figures to align themselves with the working classes.

In terms of the Folkloric influence there was a large emphasis on symbolism and dressing in abstract, homemade costumes. Many of the symbols are either related to types of work or spirit like figures and representations of the devil which I suppose links back to the warding off of evils spirits and druidic practices of sacrifice which were highly elaborated on within folklore, most likely just made up!”

On having the cast read Percy Bysshe Shelley’s The Masque of Anarchy…

“Shelley’s poem was one of the first things we encountered whilst researching Peterloo. He wrote it in response to it and it was highly controversial, he was a radical for speaking out. It was left unpublished for thirteen years, after his death actually.”

On the casting…

“None of them are models this time. It was a completely different experience to what all of them do. One of the guys couldn’t make it because he has a stall on Portobello Market and he just couldn’t pack up and reach us in time. Thankfully, we had back ups. If I see someone on the street, I might ask them but it’s Ryan who works on the cast predominantly. This time we wanted as many different accents as possible, all around the UK. That played a big part of it. We wanted even more diversity in terms of age, there are more older guys. That’s interesting for me, I always think for the most part, that they’re the ones who would buy my stuff and I like they look great too. I enjoy putting things on older people. I personally think it looks better, rather than on a super young person.”

On the inspiration behind this season’s tartan…

“Fergus O’Connor was an Irish Chartist. He toured the country campaigning for political reform, universal male suffrage and better working conditions, particularly in northern England and Scotland. He crossed prejudices of the time. At that time, the relationship between Scotland and Ireland was thorny, but he was so popular that a group of hand loom weavers created a tartan for him. That set me off on a tangent to find the tartan, which I couldn’t find. I became so obsessed that there was no turning but it was an excuse to work with tartan. I spoke to the original mills and they had tartan scraps dating back to the Battle of Culloden which was beautiful. Learning about those two mills was a real highlight of this process. We worked with them, washing and dying their fabrics in the ways in which I wanted. I wanted something that is far more subtle that the tartan of today.”

On the role of hand weaving in the collection…

“It’s partly out of necessity. The only place in the world that is prolific in handweaving is India and they generally only take carding commissions. The only other option is working with commissioned handweavers here but they rarely work in fashion, they predominantly work on special commissions and the price is too high to justify. I wanted to find a more practical way and that was to do it in house and to get a loom.

Making the fabric takes some doing. There really aren’t that many people who weave either. Finding them was a process in itself. Thankfully, there’s a course at Central Saint Martins that specialises in it and I met a few people from the course. Each different weaver has their own specialisation so it was great to be able to collaborate with them, we designed the fabric together. It enriches the creative process and makes for a better fabric. Also, it allows them to create something that will actually be made into a garment. None of them had ever made anything but samples. When we go into production, it will be great to be able to commission them.”

On drawing comparisons with his research into the Radical North and Brexit…

“It’s interesting to draw comparisons with ideas of the Radical North and what’s happening now, I guess in two ways. Firstly, in the sense that there’s a lot of talk about people not being allowed a democratic say, they shouldn’t have the vote. For some, the consequences of Brexit was that the people were allowed to vote and what subsequently happened. There was certainly naivety, so many people thought it impossible that Vote Leave would win. That bigoted view that people shouldn’t have the vote was extremely similar to to what was happening in the build up to Peterloo and what those workers were fought against. It goes against everything that people have fought for. Secondly, Brexit is a radical change and it’s interesting to see the role similar parts of the north, and south of England too, play. The towns and villages beyond our largest cities. The Brexit vote has shown that a section of the population, the majority, feel that they’ve been ignored. We need an informed society and a democracy that represents everyone. There’s still not enough focus and investigation on the causes of the vote. Much of the dialogue here in London revolves around remaining close to the EU, rather listening to the reasons behind why people voted leave and looking to resolve them. Hopefully it leads to more engagement.”

Credits

Text Steve Salter

Photography Ryan Skelton