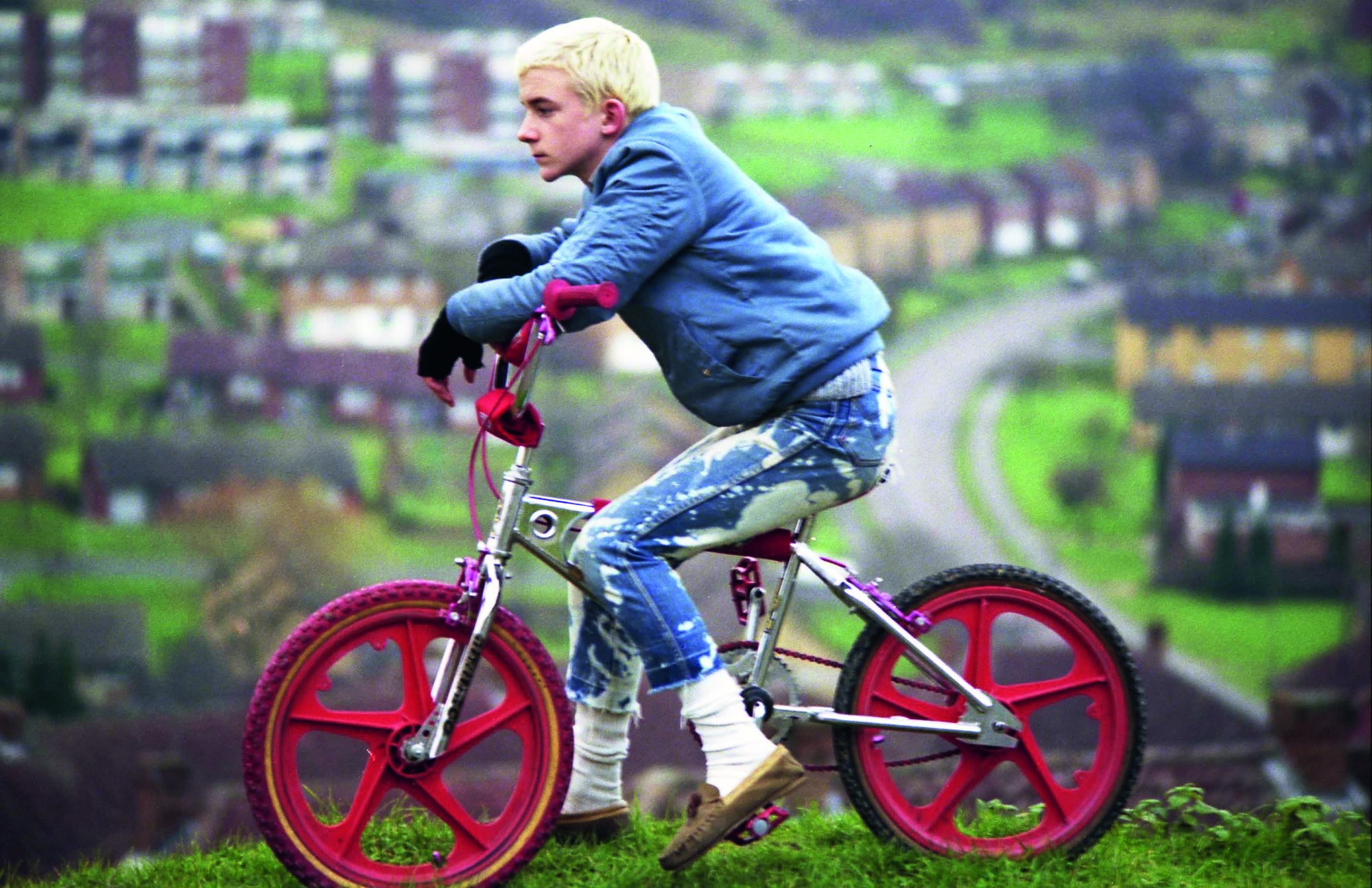

Back in 1994, British photographer Gavin Watson published Skins, an intimate look at life growing up on the council estate of High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire during the late 70s and early 80s — just as the second coming of skinhead culture had taken the nation by storm. Sporting bleached jeans with braces, combat boots, MA-1 flight jackets and buzzcuts, skinheads cut a rugged silhouette rooted in their shared working class roots. First appearing on the streets of London in 1969, skins came of age during the era of slum clearance, and were forcibly relocated from the East End to the then-new Brutalist estates.

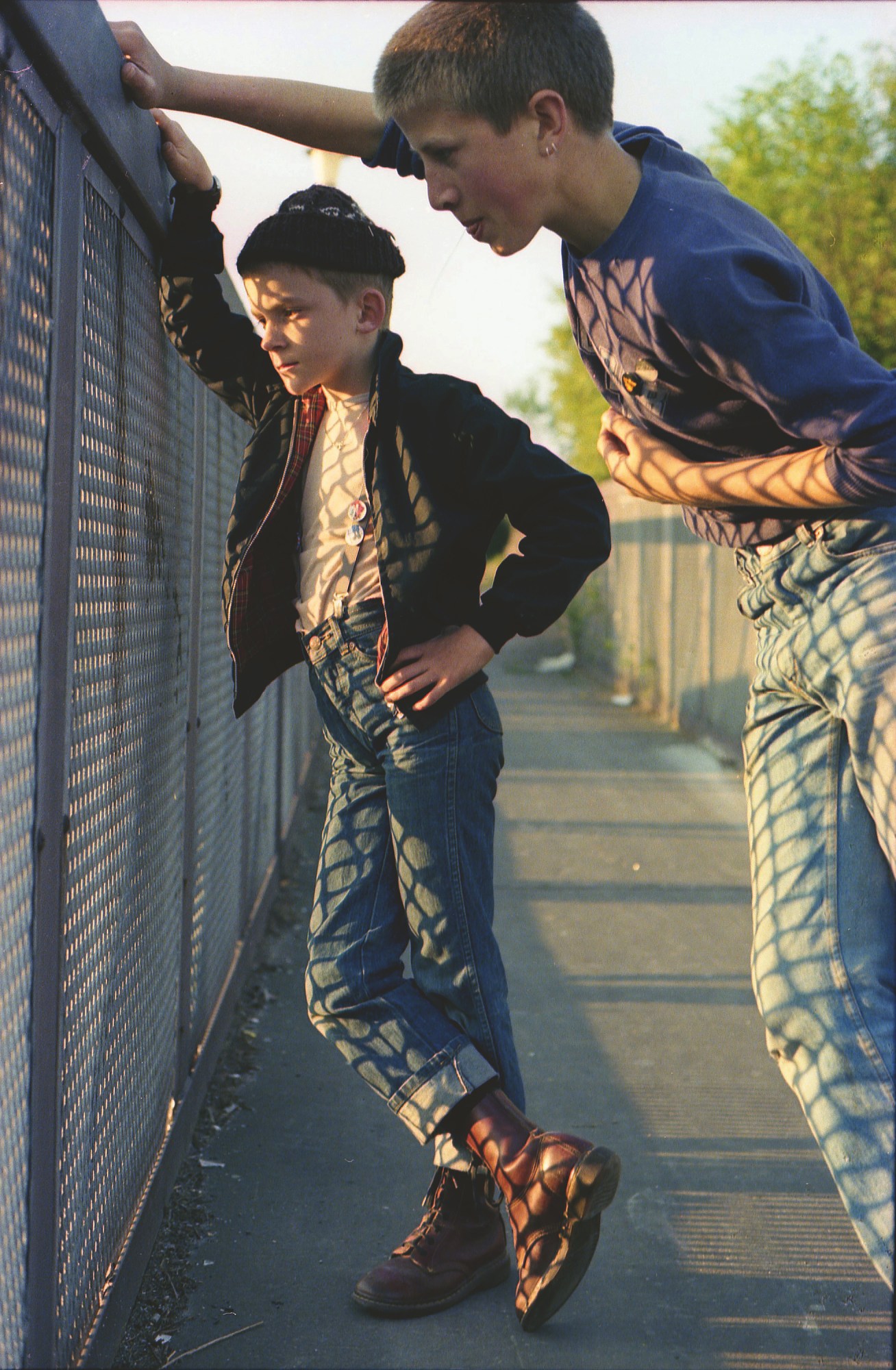

With their communities crushed and scattered, skins built a culture from the rubble and embraced their place on the jagged edge of society. They embraced the natty style and hypnotic sounds of the newly arriving Windrush Generation, which brought rocksteady, reggae and dub to record stores, nightclubs and pirate radio. The music preached rebellion and knowledge of self, its message appealing widely to disaffected youth and inspiring TwoTone, which fused ska, punk and new wave; reflecting the landscape of Gavin’s childhood where kids of different racial and ethnic backgrounds freely mixed.

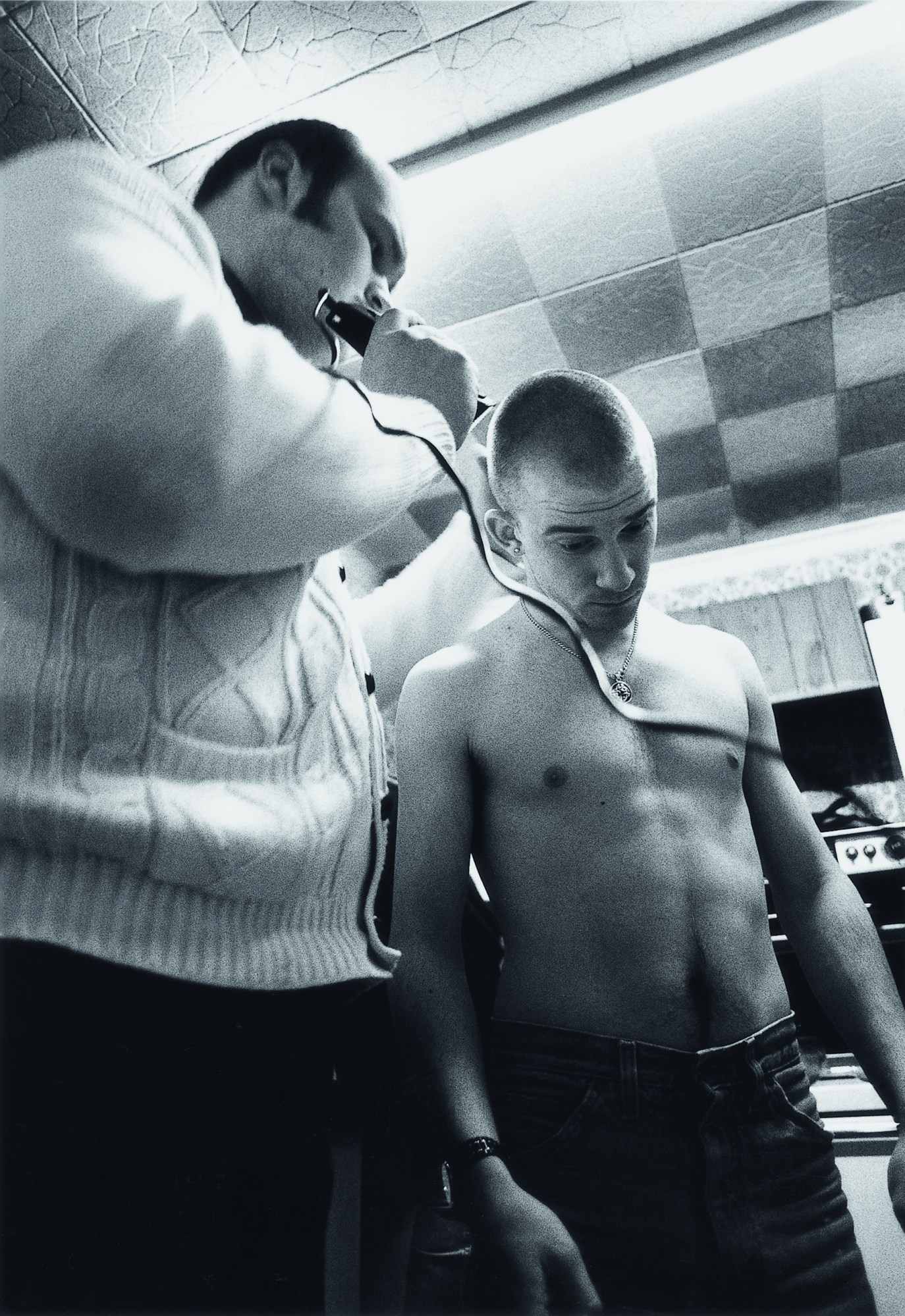

Feeling a kinship to the community, Gavin became a skinhead at age 12. On the precipice of adolescence, he put aside his love of disco and Gary Numan for an edgier vibe, sheering off his long locks to complete the transformation, which began just as he was discovering girls. The following year he bought a camera with some Christmas money and fell in love with photography the instant he saw the prints from his very first roll.

Gavin took his camera everywhere and nobody batted an eye. By the time he was 16, Gavin had amassed some 10,000 images that formed a visual diary of the Wycombe Skins, crafting a masterful coming of age story filled with romance, rebellion, innocence, camaraderie and kinship. On 17 April, ACC Art Books brings Skins back into print.

“I’m just lucky enough to be alive to talk about it, because was dangerous. I lost so many of my friends and lived in such a brutal environment,” Gavin says. “I’m a romantic, always was as a kid. I want everything to be rose-coloured glasses, so that’s why you don’t see any of that shit in my pictures. Scratch every one of those characters, myself included, and there’s this level of dysfunction and abuse coming from poverty but my photographs don’t show that. They show the joy of being 15. There’s a bright future ahead of you before you get chipped away.”

Continuing in the tradition of Bruce Davidson’s Brooklyn Gang, Gavin’s image ran counter to the mainstream media narratives of the time. Far-right extremists from the National Front appropriated the skinhead aesthetic, refashioning it as a neo-Nazi uniform designed to assert dominance and provoke fear as they organised marches and local political campaigns nationwide. The look quickly spread to homegrown fascist groups throughout Europe and the United States as portrayed in the 1998 film, American History X.

“That kept me a skinhead for longer because they were lying about us,” says Gavin. “I come from very multicultural community that had their struggles but the music united us. I think the right-wing narrative was forced on us because it made certain people panic. I’ve watched people get off-balance at my shows; they come expecting to see a load of tattooed monsters with great big pit bulls and there’s a little kid that looks like their brother.”

Rather than fan the flames of the cultural divide with images of poverty, violence and despair, Gavin sows seeds of love. His photographs are shared moments of trust, care and intimacy that remind us to hold what is good close to our heart, and that we hold the power to tell our stories on our own terms.

The first edition was rough and ready, giving it another layer of authenticity that added to its allure, while the 2023 edition is exquisitely produced, showcasing his photographs in their best light. But for Gavin, the fact that either — let alone both — editions exist is a testament to something greater at play. “It feels almost surreal,” he says looking back at how his personal, diaristic work became Skins. “It all feels outside of me; all of those tiny threads that got me to where I am today were so easily broken. These photographs have a life of their own — I believe that I was a vessel.”

In retrospect though, it seems inevitable. Original skinhead culture united the working class across racial lines, building a bond between natives and immigrants at a time when Enoch Powell was delivering his notorious 1968 “Rivers of Blood” speech. By stealing the skinhead look, the National Front sowed distrust, discord, and strife, while pushing the image of skins as violent and dangerous. That skins were both highly visible and wholly inaccessible only added to the intrigue and allure.

And so it remains today, four decades after Gavin photographed his mates on a rough and tumble journey from boys to men as they sought to create an identity and community all their own. “It’s full circle,” Gavin says, now 58. “Skins came out nearly 30 years ago, when I was going through my first Saturn Return when everything changes for everybody. It was published underground, printed with the cheapest possible materials, and wasn’t meant for anybody except a few skinheads still left in England. Then life went on — I got married, got divorced, published other books. I’m in my second Saturn Return and now I can put it to bed. It’s my streets of London song and I’ve got utter respect for where it comes from.”

‘Skins’ by Gavin Watson is published by ACC Art Books

Credits

All photography ©Gavin Watson