Activism, as the cliche goes, is in the air; but mostly it’s on the streets and on our screens. As Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests and virtual Pride parades unfold across the globe, it’s impossible to overlook the roads that were paved before us. Forming in New York in 1969, the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) was the first activist group to form directly after the Stonewall Riots. During their time, the activist group protested the American Psychiatric Association in labelling homosexuality a mental illness and the persecution of the queer community. Now, 51 years later, the LGBT+ community continue to tirelessly fight for political recognition and rights — but none of the outcomes would be possible without the change driven by the activists that came before. As always, history stands as a lesson to all future generations.

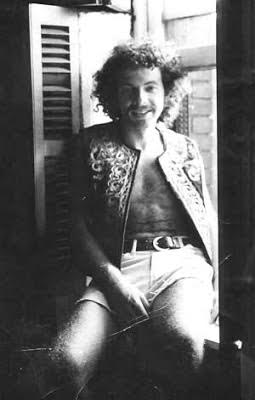

A young Jewish activist, Martha Shelley was instrumental in the creation of the GFL. The Brooklynite grew up listening to stories about her mother’s family being killed in the Holocaust, an experience, she recalls, which laid the foundations to her career; “My challenge became: what could I do to stand up for what was right?”

For Martha, modern activism has to pay homage to what came before it. “I spent a lot of time reading history and it matters that you understand what people have done and how they did it,” she explains. “It doesn’t mean that you have to stop what you’re doing. It just means you use that information to inform what you’re doing.” Now 76, Shelley has taken part in her fair share of protests and marches and has faith in modern movements. When asked about the future of activism, she offers some advice to Gen Z: “The kids know what they’re doing. They don’t need our guidance. Go forth and do what you’re doing and fight for what you believe in and don’t listen to people who tell you to wait. Don’t wait, because the planet is on fire — and anybody who tells you to wait is just too comfortable.”

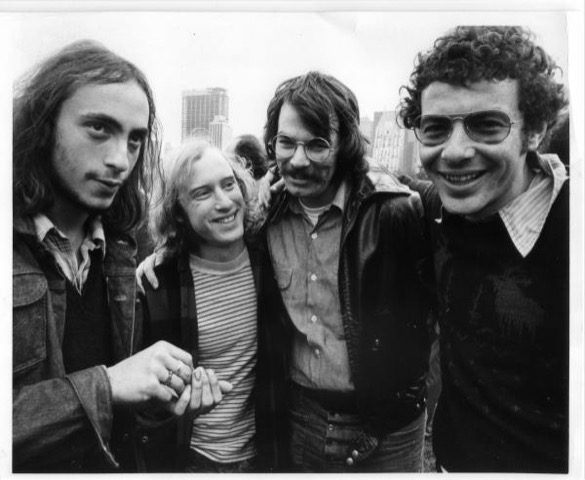

John Knoebel, a fellow GLF member, experienced homophobia throughout his life. He vividly recalls leaving a gay dance in 1970 and being “gay bashed” in Greenwich Village after four men jumped out of cars and beat him and a friend. John was knocked unconscious from the attack and required 14 stitches in hospital. For him, queer activism was necessary in finding his self-worth as a gay man. He explained; “There was a personal rationalisation I was important and my life mattered and that there was a fight that needed to be begun.”

An advocate for civil rights and queer liberation, John met Black Panther co-founder Huey Newton during a press conference at Jane Fonda’s penthouse on the Upper East Side. During that time, Newton had written a statement on gay liberation while in prison. Afeni Shakur, the mother of Tupac Shakur, approached Knoebel in an effort to encourage a dialogue between the Panthers and GLF. Although only a few meetings came out of the conversation, John is certain that this level of inclusivity and intersectionality in the Pride movement is key.

“If there’s a strong belief or struggle behind [an organisation] then it has a really good chance of sticking around and becoming valuable, even if it’s capable of being lost in the clutter of the internet. I think the internet is an amazing tool that can only make things broader and more diverse. We had centrality in 1969, but now there’s so many voices.”

Ellen Broidy was the organiser of New York’s first ever Pride march, held on June 28th, 1970 in honour of Stonewall. “We thought this was going to be part of a great revolutionary upheaval,” she recalls. “We were sure that the revolution was just two blocks away from us and if we can just walk those two blocks, we turn the whole damn thing around.”

Officially titled Christopher Street Liberation Day March, Ellen’s invention quickly became a phenomenon. “I think it’s absolutely amazing,” she says. “We were taking to the streets as people who had had enough, exactly like the BLM protestors today. They didn’t wait around for somebody to make fancy banners and build floats and have parade marshals. It was about grabbing the moment.” Speaking about sustaining the momentum of gay liberation, Ellen is clear about its future direction. “I felt 1969 was our moment, but it’s not our moment now. We need to listen to the other leadership that is coming up. We need to listen to Black and Brown voices. My comrades and I didn’t pay enough attention to reach out to the Black Panthers or the Young Lords (a Puerto Rican group in New York). We didn’t look around the room, our own room and see who was and who was not there, whose voices needed to be heard, or whose voices were missing.”

As a new generation takes to the streets, the pioneering activist leaves a final message: “It’s different with each generation; the challenge is remembering the history and wondering why we haven’t come any further. Our revolution didn’t happen, but maybe it’s happening 50 years after we thought it would. We have to get rid of the Donald Trumps and the Boris Johnsons of this world,” she muses.

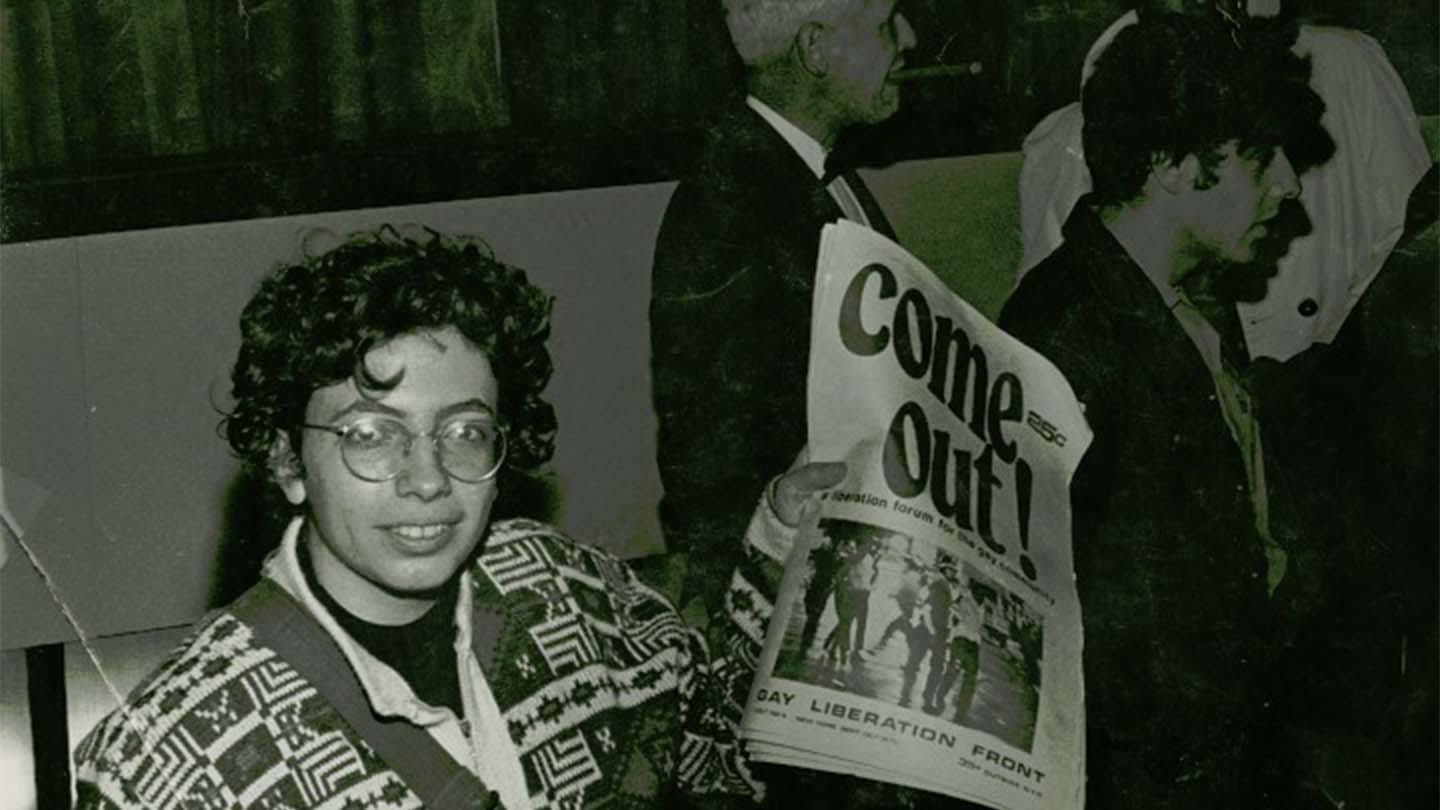

Author and activist Perry Brass stood as an editor for the GLF’s radical paper Come Out! Growing up in the deep South, Perry was exposed to conservative politics early on, which later revolutionised his attitude towards activism. For him, dismantling performative activism, in any era, is vital. “Understanding the vulnerability of Black people, gay people, or lesbians is powerful,” Perry says. “It says ‘there’s a piece of me that connects with that vulnerability’. You can have all the activism you want, but until you go to that level, it’s just something you can put on. I can’t stand the idea that some people think okay to just wear a BLM t-shirt — it’s much deeper than that.”

When it comes to the age of new generational change, though, Perry has his concerns over technological activism. “Now people are having digital demonstrations and digital get-togethers. It’s very hard to have that visceral reaction digitally; the reaction that says this is something within my heart and my guts.”

While the methods of activism continue to evolve, past generations seem to agree that diversity and a wider scope of voices are the future of any movement. As we continue to push for progress, it’s time we acknowledge the Sylvia Rivera’s and Marsha P. Johnsons of our time, threading diversity into the heart of our activism. Ellen perhaps puts it best: “However we articulate our goal, we must reach it together in a world of equality. We leave it in your hands. You’re building the world now, not us, but acknowledge the bricks we laid.”

Credits

Imagery courtesy of Gay Liberation Front activists and the New York Public Library