London College of Fashion graduate, Shakaila Forbes-Bell, says positive changes towards race and diversity need to start from within the industry.

Like Snow White’s stepmother — but less sadistic — the fashion industry wields influence and power. We all long to hold up a magazine or look down a runway and see some reflection of ourselves. We’re not trying to be the ‘fairest of them all’ but just see some confirmation that our type of beauty is not only celebrated but valued.

In the case of Black and Minority Ethnic women (BAME), their images are often absorbed rather than reflected leading to instances of cultural appropriation — the universal sign for ‘Yes, we like this about you but no, you can’t sit with us.’

Fashion marketers often overlook cries for racial inclusion, claiming that it is not their job to sell accurate representations but simply garments. What they fail to realize is that this monolithic and whitewashed idea of beauty is financially damaging. Social Identity Theory states that our race is a pivotal factor in shaping our identity and (Klemm, 2014) argues that self-identification is a key factor in shaping how we respond to advertising. For example, in Deshpandé and Stayman’s 1994 study, participants found same-race spokespersons to be more trustworthy and subsequently held positive attitudes towards the advertised brand.

A similar study found that Black consumers rate ads featuring Black persons as more favorable than those exclusively featuring Whites (Appiah, 2001). More recently, research I have conducted at London College of Fashion found that Black women are actually more likely to purchase products advertised by same-race models.

It appears that the so-called ‘brown pound’ will be remaining in brown pockets until fashion whole-heartedly embraces diversity. Until then we’ll be filling our “Black Models Matter,” bags with love notes written to Nykhor Paul, Leomie Anderson, and Zac Posen complete with a compact mirror — to witness the beauty they chose to ignore.

Instagram posts are becoming more and more homogenized. London College of Fashion graduate Lisa Strunz says it’s time to be brave and post something new.

Since Instagram was in launched in 2010, its users have been sharing 80 million photos on average per day (Instagram Stats, 2016). That’s more than 3 million an hour, more than 55 thousand a minute, and more than 900 every second.

Theoretically, that should lead to an enormous variety of pictures. However, users might notice that Instagram posts are looking more and more homogenized: The travel essentials, the morning macchiato, the naked legs on white bed sheets. Why has diversity become so rare in the world of Instagram?

It can be best explained by the chameleon effect (Chartrand & Bargh, 1999), which describes the human tendency to subconsciously mimic other peoples’ gestures, postures, moods, speech patterns, facial expressions and mannerisms.

To mimic someone increases the chances to be liked by him or her, and serves as a social glue. This, in turn, is satisfying one of our fundamental human needs, to affiliate and belong (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Similar looking Instagram pictures are therefore nothing else than the attempt to socially fit in and be accepted.

On the other hand, seeing repetition over and over again can lead to boredom (Jiang et al., 2009) and eventually to disliking the subject matter (Markman, 2012). Too much homogeneity on Instagram could hence have the opposite effect: no likes, no acceptance, FAIL.

So be brave. Post something new. Or at least shake up the items in the travel essentials.

J.W. Anderson, Rick Owens, and Ann Demeulemeester have all shown gender neutral collections on their catwalks. Joel Masson looks into what else we need to do to prove that unisex and androgynous clothing provides a new space of freedom for men and women.

Despite the success of Gaultier’s 80s Man Skirt, clothing design is still mostly gender polarized. In recent years, though, a shift towards either unisex, or gender diverse clothing has surfaced.

There are several factors, which compose an individual’s sexual identity. Traditionally a combination of gender identity, sexual orientation, and other such factors that ultimately form what our sexual identity is, suggests perhaps more fashion types could read Geng Cui & Pravat Choudhury, (2002) for insight into diversity marketing. Here authors showed that a more diverse target market, usually equated to a more successful campaign and ultimately brand image.

J.W. Anderson, Rick Owens, Rad Hourani, and Ann Demeulemeester, already know this perhaps and have presented either partially gender-neutral collections or, collections in which the models are mixed up! It’s a “Who wears what? Who cares!” stance that has below the radar intelligence.

High-profile brands have begun to notice too. And to use some old- school Zoolander rhetoric, diverse models who don’t conform to traditional gender identities are “so hot right now.”

This observable shift in how gender is portrayed in shows and campaigns capitalizes on the space occupied by transgender individuals or those who don’t formally identify fully with either sex. And if it paves the way for both designers, and consumers to have less rigid guidelines when producing and purchasing clothing… what’s not to like?

Valerie Steele highlighted the fact that unisex and androgynous clothing provided a new space for freedom for both men and women. Can we say that this may very well be the new normal for both luxury and mainstream fashion brands in years to come?

We’d like to.

READ Cool Psychology: A Look Into Fashion From A Psychological Perspective

READ Messy Concepts: The Challenge Of Diversity

Credits

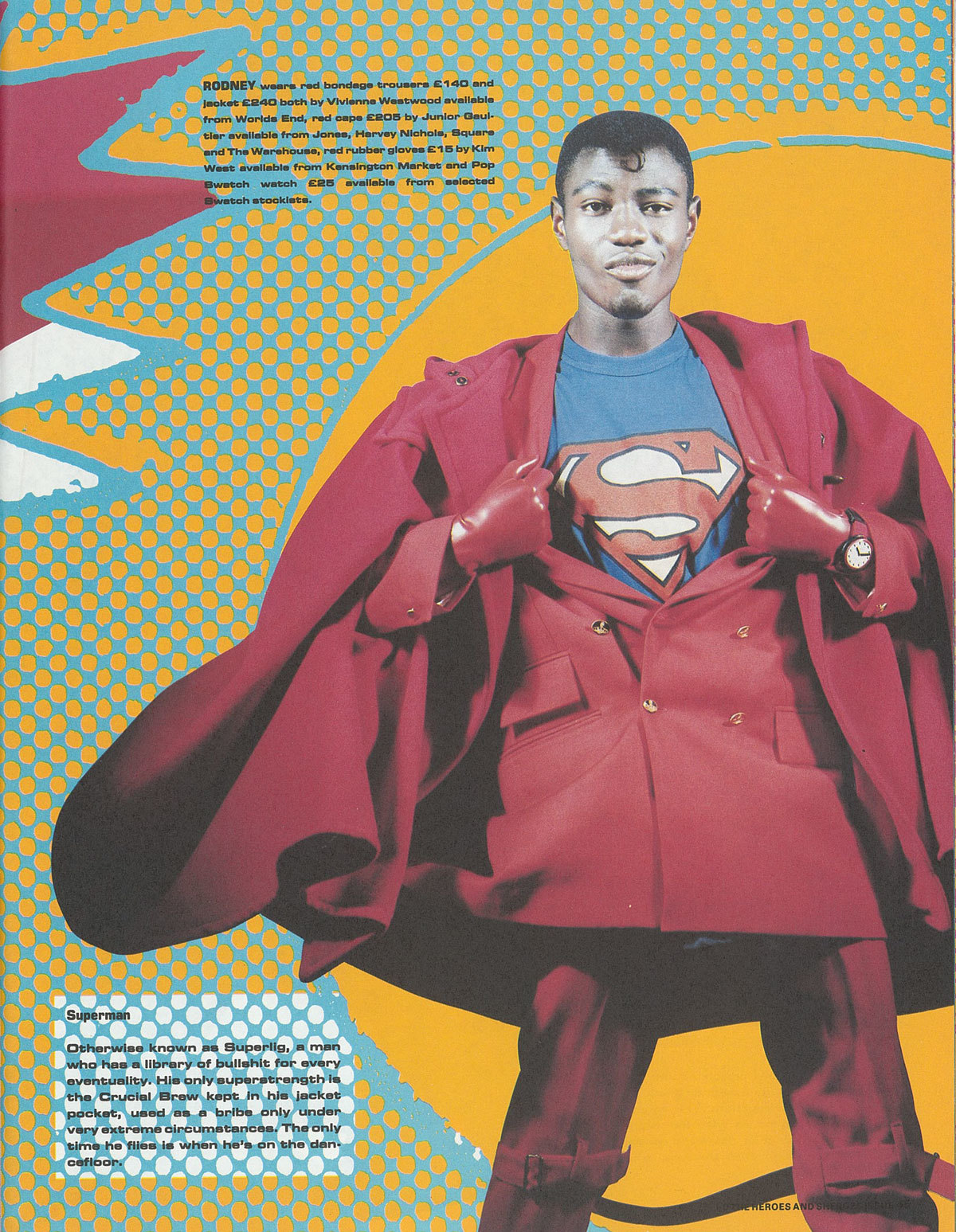

Photography Kevin Davies

Styling Caryn Franklin

From i-D No. 63, The Heroes and Sheroes Issue, October 1998