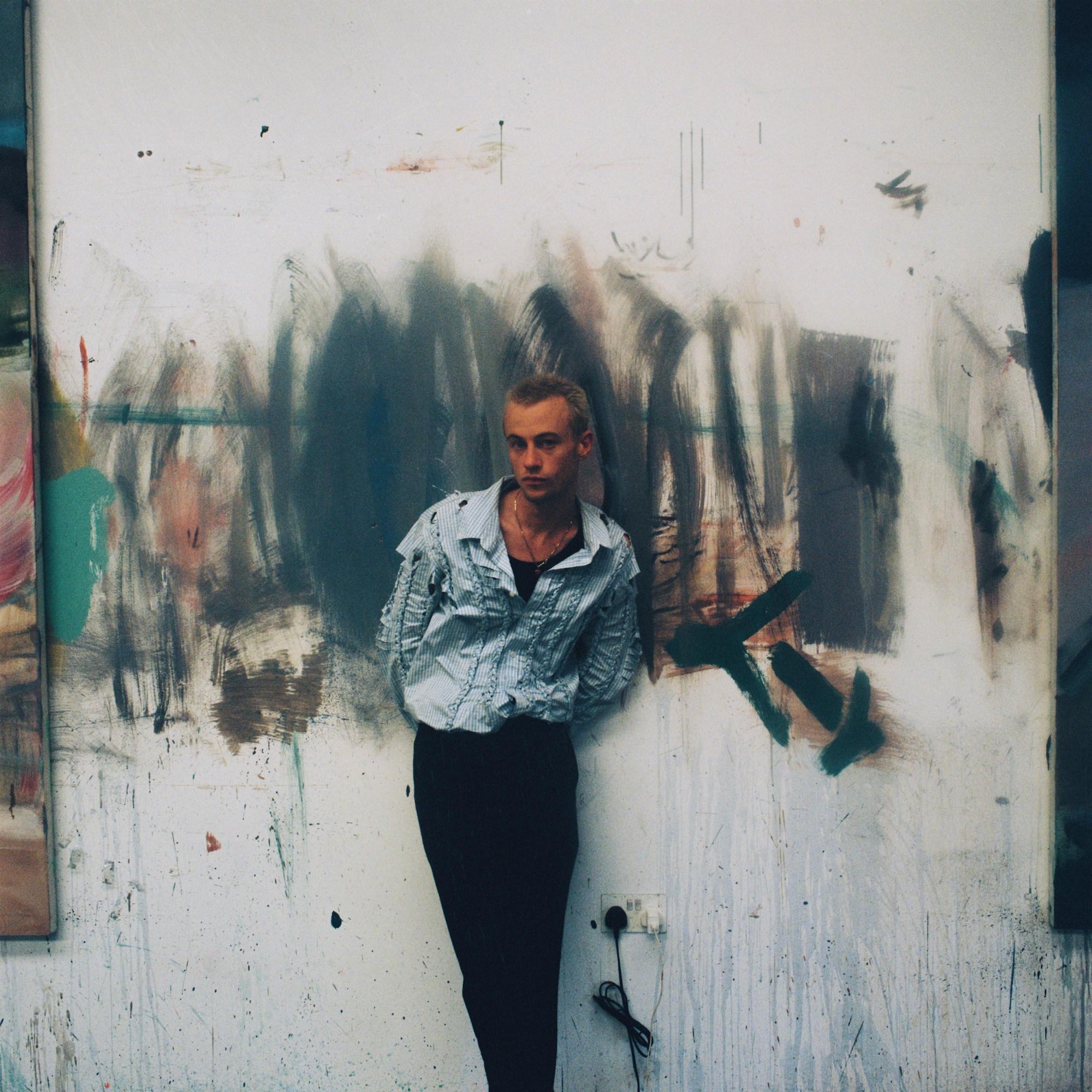

Not too long ago, George Rouy traded in London for a slower pace of life in the sleepy town of Faversham in Kent. He moved into a 19th-century evangelical church, where he now sleeps below a stained glass window and tends to his sprawling garden, and rented a studio space in a business park a short walk away. The artist could be found there, labouring away on a series of giant figurative paintings rendered abstract by his energetic brushstrokes and a fleshy palette of browns, pinks and taupes. They captured human essence with all of its complexities and frictions rather than people in their truest form.

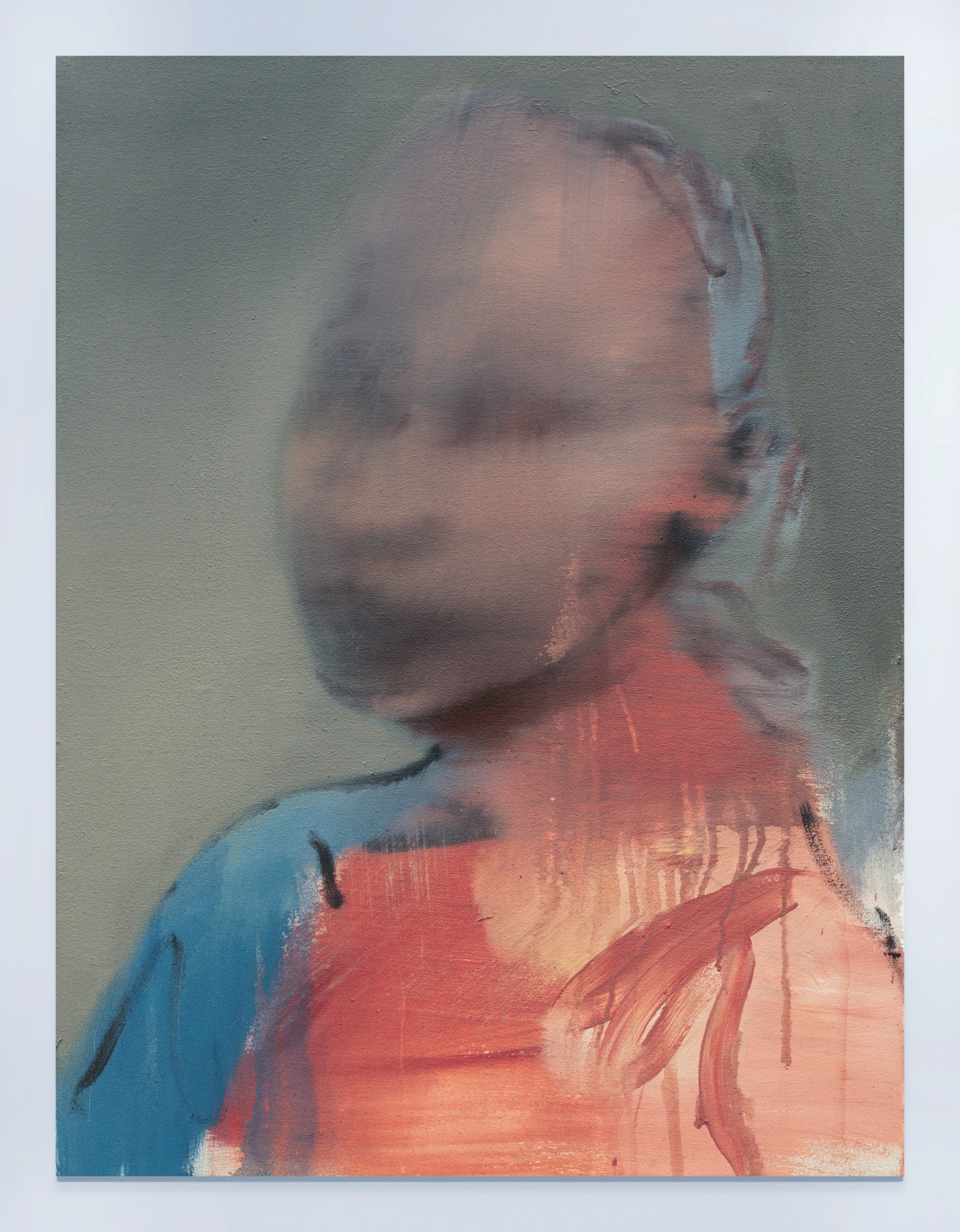

On the summer’s evening I visit, he bounds between the two paintings that remain. The paintings are full of ruptures and tension, breakage points where the stomach would be and a swirl for a face. “Without sounding too spiritual, there’s this other that surrounds us,” George says with a cheeky flash of his grills. “I’m interested in when we shut our eyes, and we feel our own bodies, our own weight and anatomy, how we link to our surroundings and the external, and how you think about that in relation to painting.” For the artist, the space around people is as much a part of the image in the way that those interactions can “distort, blur and bleed.”

Since finishing his studies at Camberwell College of Arts in 2015, the 29-year-old artist has grown more confident in his work: moving from a static, sculptural style to the breathy, tumultuous scenes he will reveal at his solo show at Nicola Vassell Gallery in New York on 7 September. Today, it’s less about the physical and more psychological, he says. Although all his shows are named after some kind of anatomy: Body Suit was the most recent, and before that Clot and Shit Mirror. For Endless Song, he was interested in the transference of culture through time, how a human exchange can precede us and influence generations to come.

“I’ve always really wanted to explore the idea of a mass,” he says, “the interactions between multiple figures, and the conflicts and contradictions of the metaphysical part of being rather than the actual physical part.” It’s most obvious in two of his paintings in his series of almost a dozen, which all complement each other in subject and tone. The first depicts figures being crushed by several bodies in a way that could appear sexual, violent or suppressive. “There’s the feeling of suffocation,” he says, that’s counteracted by a sense of transcendence in another image where three abstract figures lift someone who appears almost weightless or dead.

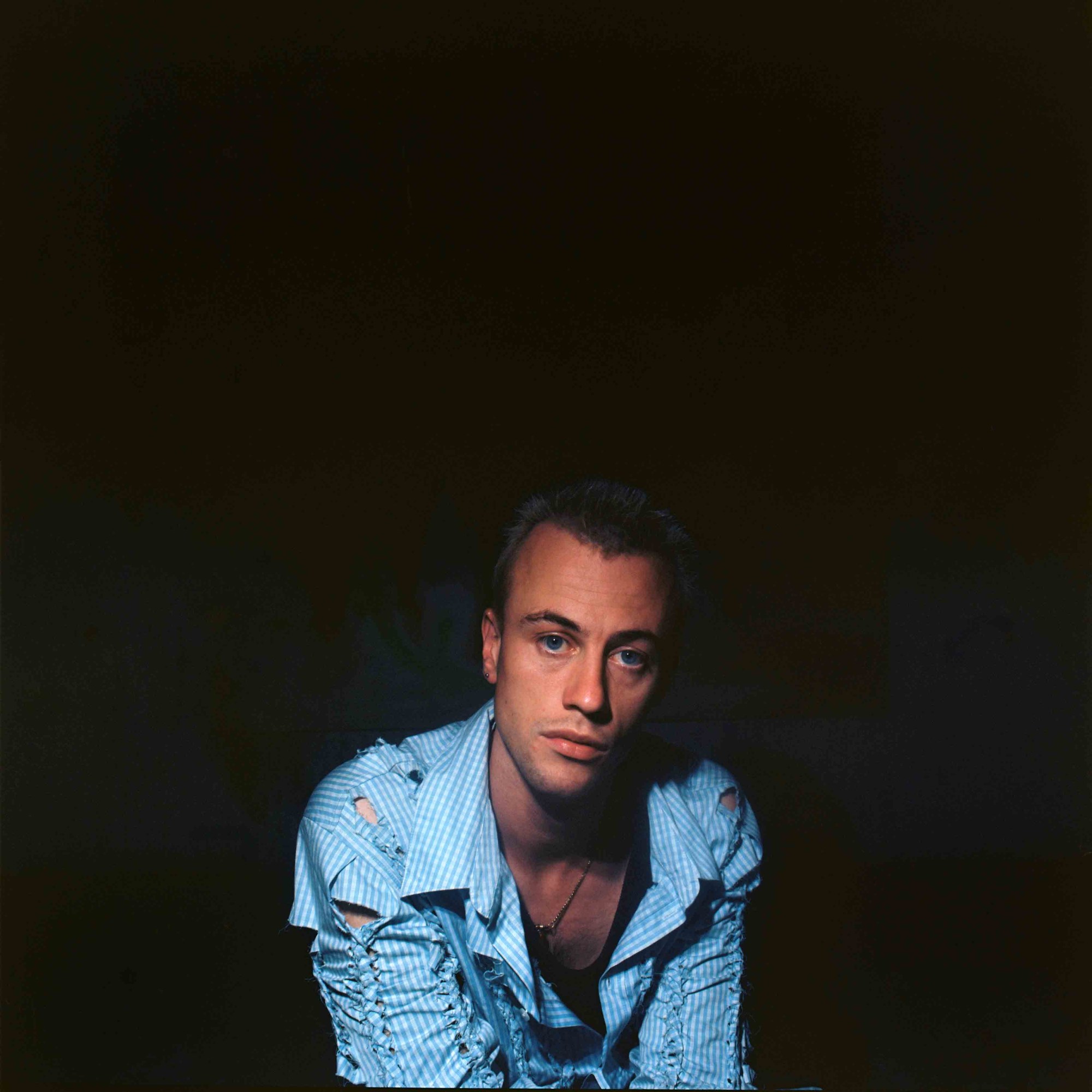

For the artist, it’s important that the work isn’t always “beautiful or easy, or even safe,” he says, “there can be tension that’s uneasy.” Often, his figures will break the fourth wall and confront the viewer in a way that can be haunting, their eyes piercing into your soul while the rest of the painting is a sea of abstraction. “I don’t like the idea that there is a space beyond you, the viewer, and the figures in the piece that’s depicted,” he says. “They’re almost like mirrors to something rather than a scene that could be going on over here; you’re part of that interaction.”

The nudes come from his imagination, although he does use reference images found on the internet for collages he creates in Photoshop to plan the scenes. George says he likes how paintings can be informed by photography and the flatness of scenarios that happen within images that you didn’t create yourself. “There’s a real shift in how these transfer in the painting when you’re looking at them in an abstract point of view, in terms of how you’re dismantling an image and the body,” he says. Cecily Brown and Jenny Saville were good at that, he says, calling them “the elders of figurative painting.”

George’s work is often eroticised, although the artist doesn’t see his figures that way. “I’ve done paintings with clothes on, and they’re more sexual,” he says, believing there is a suggestiveness that comes from choosing which parts of the body to drape. What he does enjoy, though, is when his work is uncomfortable and “you feel like you almost shouldn’t be looking in a way, something is off about it, and it’s not enjoyable.” He believes art should hit those pressure points where the viewer is being seduced even though the subjects aren’t that seductive.

In some ways, there’s an androgyny to the people he depicts, his work a heady mix of movement and commotion rather than the clarity of human forms. But there’s clearly diversity in the ethnicities he paints. “I think over the years, I’ve become more self-assured knowing that I’m doing things with the right intent and sensitivities.” Now, “it feels connected to the viewer, rather than a voyeuristic, almost separate thing.” He says, “Everyone seems to be able to have a way of entering, and it doesn’t feel like it has pushed people away.”

But this hasn’t always been the case for George. At the opening of his first show at Hannah Barry Gallery in Peckham in 2017, he found himself confronted by a videographer who challenged the depiction of Black figures. “It went on for quite a long time, and it was a really interesting experience,” he says. “It wasn’t a nice experience, but what it did do is — well, first it made me scared — but then it put me on this journey of wider perspective and really getting to know your position as an artist, and trying to do good.” Now, he knows the work is about human essence, which he thinks is what makes it comfortable or palatable for people.

George comes from a family of artists: his sister Elsa is a painter whose work explores female sexual expression, hedonism and the imperfect self, while his younger brother Alfie creates eerie, otherworldly paintings. Growing up in Sittingbourne, one town over from the one George now lives in, their parents were very pro art, although their dad was a hairdresser and mum worked in an office. It was a lovely upbringing, he says, which made me wonder where the darkness that seems to lurk in all three children’s work comes from.

George says for him it’s his OCD, which presents itself in the form of intrusive thoughts of guilt and shame. “Everyone has these tendencies and thoughts, but once you become more accepting of what kind of state or allowing these conflicts within one’s self, they come out in other ways,” George says. “OCD can traumatise in a certain way, and I think you know the darkness. It’s not a bad thing if you can eventually get over it.” His mental health informs his work, he says, but it’s not about that. Art has always been there as a constant, an escape from those feelings, “which I think is a testament to the notion of making work and being creative,” he says.

“Playing is a really important thing and should have more of a part of society,” he says. “That’s half of what I do; I test and experiment.” From his almost vampiric aesthetic: gold grills for canines, bleached hair and vintage-inspired dress to his home in a Grade II-listed church, George has fun in the way he presents himself. The artist straddles the line between deep thinker and loveable rogue but isn’t all that pretentious: he’s quick to laugh about the fact he’s not able to drive the old BMW that sits on the ground floor of his studio because he’s failed all three of his driving tests so far. In many ways, much like his work, he’s full of energy, life and motion, captivating but also, as he might want it, not all that easy to read.

George Rouy’s ‘Endless Song’ opens at Nicola Vassell Gallery in New York on 7 September through to 21 October

Credits

Photography Alfie White