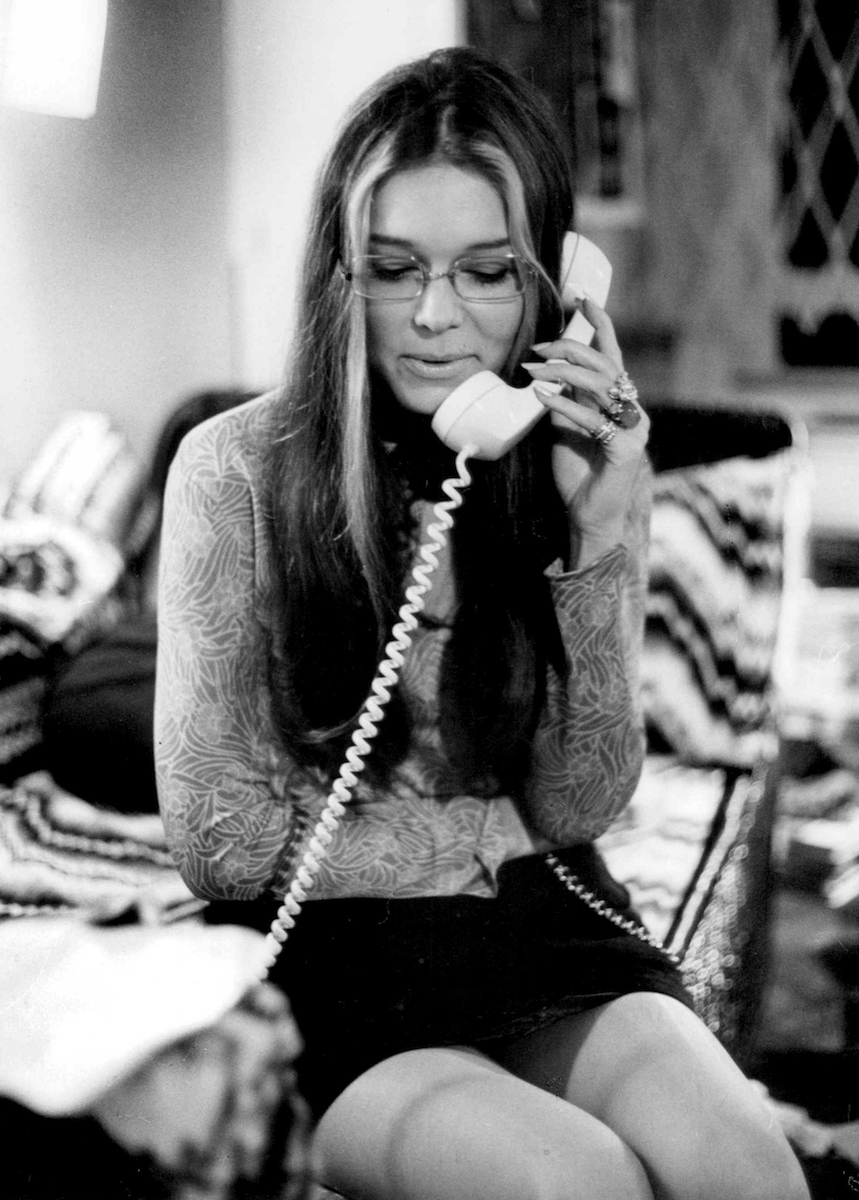

Gloria Steinem’s political life has been very well-documented, to say the least. Since the late 60s, she’s remained one of second-wave feminism’s most recognizable figures, if not its most recognizable face.

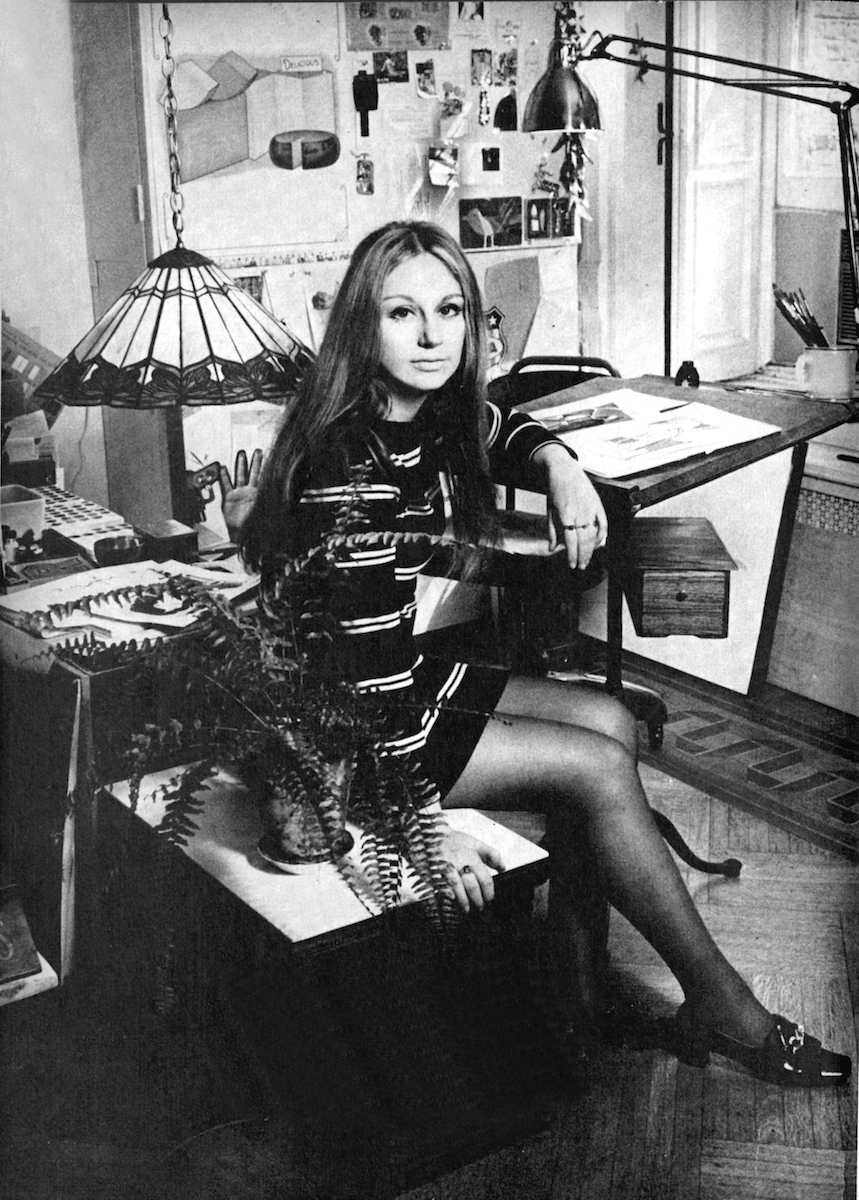

It’s said that behind every great man is a great woman — likewise, behind every great woman are great female friends. Here we offer a personal look at one of Steinem’s closest and most long-lasting friendships, with the visual artist Barbara Nessim. Nessim was one of the magazine industry’s first female illustrators — her drawings have graced the covers of TIME, Rolling Stone, and the New York Times Magazine, among others — as well as a pioneer of computer art. Indeed, her work is so influential that in 2013 the Victoria and Albert Museum honored her with a career retrospective, Barbara Nessim: An Artful Life.

When the pair met in 1961, they were a 26-year-old freelance writer and a 21-year-old freelance illustrator trying to make it in New York City. The following year, when Steinem moved her few belongings into Nessim’s sparsely furnished one-room studio on West 71st Street, their joint domestic life proved so successful — fun, uncomplicated, mutually inspiring — that they stayed together for six years.

On a recent May afternoon, we gathered in the living room of Steinem’s apartment in Manhattan — the last address the two women shared, and where Steinem has stayed ever since — to discuss their many-decades-long connection.

Kate Bolick: Could you tell me your origin story, how you met? I read somewhere that it was a double date.

Barbara Nessim: I was dating Henry Wolf, one of the better art directors, who really changed the graphics of the fifties and sixties and seventies. Gloria was going out with Robert Benton, who was Henry’s assistant at Esquire magazine. So we would all go out to dinner and one evening I told Gloria I was looking for a roommate.

When you were talking on those dates, what were you drawn to in one another?

Gloria Steinem: Well, first of all, Barbara could do all these things I can’t do. She could just do all these magical things. She was always, as now, authentic. Utterly, totally herself. No deception. She’s just great, which allows me and others around her to be that way. We were both freelancers, so we were both in the position of trying to have an idea for a specific theme — I mean, I would do the writing, and she would do the illustrations, but the problem with the freelance life is, well, it’s a very distinctive life! That was part of the job, though. To this day I’ve never been able to have a job in an office.

Did you influence each other’s work during those years?

GS: Yes, absolutely. I learned from Barbara how to look at form rather than function. She’s so visual.

BN: I worked by the window and Gloria worked at the other end. It was like we had our own apartments. We were quiet, we did our own things, and then we would talk, and I would read Gloria’s stories or show her my illustrations. We were in our own worlds. The way we lived together — which was I think very interesting and very natural — was that we never had our own beds. We had a bed in the sleeping balcony and a daybed in the other room. Whoever got tired first went up to the sleeping balcony.

GS: And whoever came in last if we were out.

BN: It never occurred to me that we would have our own beds or our own anything; we just shared it all.

Did you ever have conflicts? And if you did, how did you go about resolving them?

GS: It would be very hard to ever have conflict with Barbara.

BN: Right, I don’t remember any.

GS: The truth of the matter is that in addition to living together there we were also semi-living with the men we were with. We weren’t home all the time. But we always had a place of our own. I don’t think ever in my life I have transferred all of my books and things to a man’s place. This was our nest.

BN: That was the most important thing.

So you enhanced each other with different ways of seeing the world?

BN: Gloria was interested in politics and I couldn’t have cared less. Being five years younger was a lot then. I was interested in going dancing, doing work, having fun, having my friends, but not politics. I’d always tell Gloria, “Why would I be interested in politics when everybody lies? It’s all one big lie! I’ll just vote Democrat. Who are you voting for? Whoever you’re voting for will be the best person!”

Did it change your friendship when you finally lived apart?

GS: Not at all. It’s like if you move out of your family’s house, you’re still family.

BN: It’s like sisters. You can’t live in one room with someone without feeling like they’re your sister. But with the five years between us, and having different friends, different interests, and somewhat working in different worlds — you respect each other. I’m so glad she’s here!

You laugh easily together. You share the same sense of humor, which seems a very important glue in friendship.

GS: Don’t trust anybody who doesn’t have a sense of humor!

How did getting involved in the women’s movement change your relationship to friendship more generally?

GS: Women’s friendships had always been crucial to our lives. For instance, when other female freelancers arrived in New York, we all shared our lists of good editors who didn’t always ask you to go to bed with them afterwards. We all tried to help each other. But with the women’s movement came the realization that this support was crucial; that unless you had a group of people who share your values, and support each other, you probably can’t do it by yourself. It was a political necessity.

BN: In my case, with art directors and doing illustration, I didn’t even realize that I was one of four major illustrators of the female persuasion.

I’m curious to know how both of you would define friendship. What would you say it means to you, and has that definition changed over time, or remained consistent?

BN: Trust.

GS: I think of romance as the most intense version of curiosity. Part of the reason it’s so intense is because we have these masculine and feminine roles, which we made up, so we’re looking for the rest of ourselves, if you know what I mean. But nobody can be the rest of yourself. So it’s intense, but it doesn’t last necessarily. In romance you want the other person; in love you want what’s best for the other person. So I would say in friendship you also want what’s best for the other person. You identify with them or empathize with them and just care about them so much that when something good happens to them it’s like it’s happening to you.

BN: Love is big, it’s universal, there’s no end to it, it just grows, and I wish everybody thought that way.

What about the early days of the women’s movement? Friendship was essential to the collaborative work that needed to be done, but there must have been differences. I’m thinking in particular of Betty Friedan being unfriendly, basically.

GS: Well, I didn’t really know her. She was a decade ahead of me and the book that she’d written — which is very valuable — is about women being in the suburbs, and college-educated women being like: “There must be more to life than this.” I thought, “Great, that’s true, but that doesn’t mean me. I’ve always been working and still I’m having a hard time.” It was just two separate things. I don’t think I’ve seen her a dozen times in my whole life.

BN: A different generation. A different lifestyle.

GS: It was also a different focus. The part that got to me mostly were women who were a bit younger than I who had been in the Vietnam movement and the civil rights movement. Even in those movements we loved, women still were supposed to get the coffee, which made them say, ‘OK, enough, we need an autonomous women’s movement.’ And that related more to my experience.

Do you have any secrets to long-term friendship?

BN: No jealousy. I think that’s a good secret. Be who you are. Appreciating the other person and who they are. There’s only one of you! We are who we are, and I’m never going to be you, and you’re never going to be me, so appreciate each other and the friendship that you’ve built.

GS: Trust. Authenticity. I think some folks worry too much about regularity. It’s not about how often, necessarily. It shouldn’t become a duty that you do whatever once a month. It’s just that the person is always there in moments of celebration and sorrow.

One of the rewards of long friendship — I’d even say surprises — is that you wouldn’t have predicted your life, and you wouldn’t have predicted mine. Once it happens, you think it’s so great because we’re on our own journey, but through friendship you experience someone else’s journey too.

Credits

Text Kate Bolick