This article originally appeared in i-D’s The Acting Up Issue, no. 349, Fall 2017.

Two boys come home after labouring on the farm, cook tea and settle in for a boxset evening in front of the telly. They watch some episodes of HBO’s Vinyl, a few movies from the queer canon (Moonlight, Brokeback, Weekend) and a little Summer Heights High for comic relief. Then they spend the rest of the evening working out how they’ll have sex in the countryside tomorrow night.

Before your imagination runs wild with ideas about an X-rated episode of Countryfile, these are two actors planning a pivotal scene for God’s Own Country, writer and director Francis Lee’s debut about a romance between two young farmhands, Johnny and Gheorghe, in rural working-class Yorkshire. The cosy cottage times are those of the actors Josh O’Connor and Alec Secareanu, who in preparation for their on-screen love affair lived together on a farm in Keighley. And it’s from here, after dinner, that they’d settle down to work out how best to tackle a roll in the mud the next day.

“I remember being in our cottage with the choreographed points of the sex scene on the wall,” says 27-year-old Josh, who plays the brusque young farmer Johnny Saxby opposite Alec’s mild mannered migrant worker Gheorghe. “We had two pages. It was like a dance. Johnny grabs Gheorghe. Gheorghe’s left hand grabs Johnny’s hand. They fall to the ground; they punch each other in the chest. We choreographed it in minute detail.”

But we are a few steps ahead in the lovers’ dance. God’s Own Country begins in bleaker fashion as a reluctant Johnny takes over the family farm after his dad has a stroke. His management skills, however, are pretty special. “Johnny’s experiences are waking up, farming, getting pissed, vomiting, casual sex, vomiting, going back to bed and waking up and farming again,” Josh explains, in a photo studio on a hot summer’s day in London. “Johnny is someone who has no love. He doesn’t receive love, is unable to give love or be vulnerable. He’s just working, binge drinking and having casual sex.”

A graduate of the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School, Cheltenham-born Josh is no stranger to playing binge drinking youth, getting an early break in Bullingdon Club satire The Riot Club. In fact he’s adept at traversing class lines, from work on Bridgend, a teen suicide drama set in working-class Wales, to the quainter environs of lighthearted Sunday night period comedy The Durrells. God’s Own Country is a bracing departure from the latter; the opening scene sees Johnny have his way with a young auctioneer at the cattle mart in the back of his trailer.

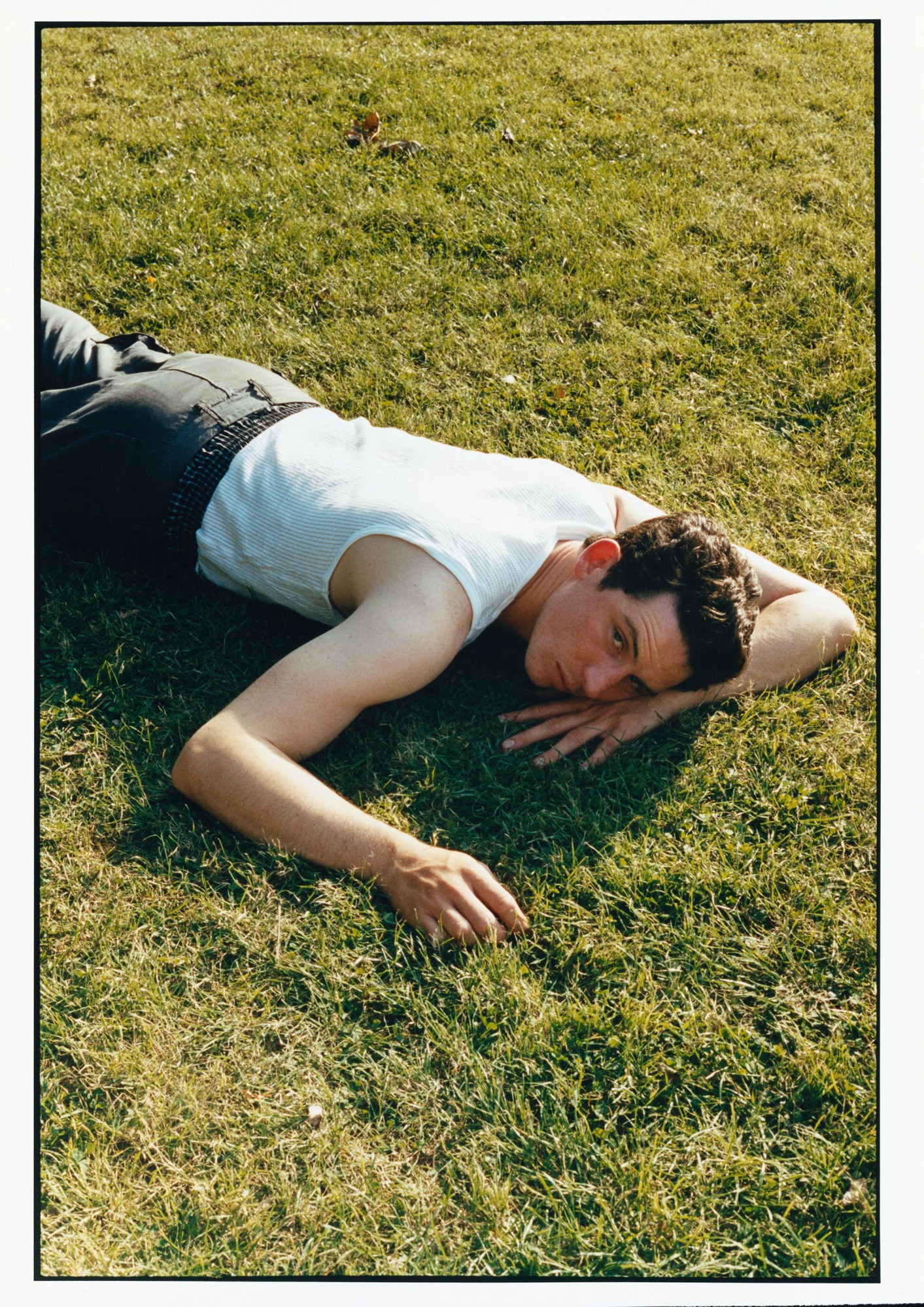

Josh wears vest stylist’s own. Trousers Stone Island. Briefs model’s own.

Johnny’s emotions seemingly run cold, but the arrival of the handsome hired help throws him. The sole respondent to the family’s advert for a temporary farmhand, Gheorghe encounters deep resentment from his new boss when he starts work. It was a reaction the filmmaker Lee nurtured by keeping the leads separate for the first weeks of filming. As on-screen romance blossomed, the actors moved in together, hence all those cosy nights in watching box sets. This quest for authenticity stretched throughout the shoot: everything was done chronologically; all the scenes of animal husbandry were real.

“We learned to give injections and skin rabbits and birth lambs and even make cheese. It was pretty intense,” Alec says with a laugh. He arrived on set from the warm spring of his native Bucharest to begin work on the film in the sharp Yorkshire cold. “The first two weeks were pretty hard. I had to go straight to working on the farm, which I really wasn’t into,” he says, with the same soft intensity that makes his character such a charmer. “But that helped build the character because Gheorghe may have had the same experience when he came to England, the same depression and isolation.”

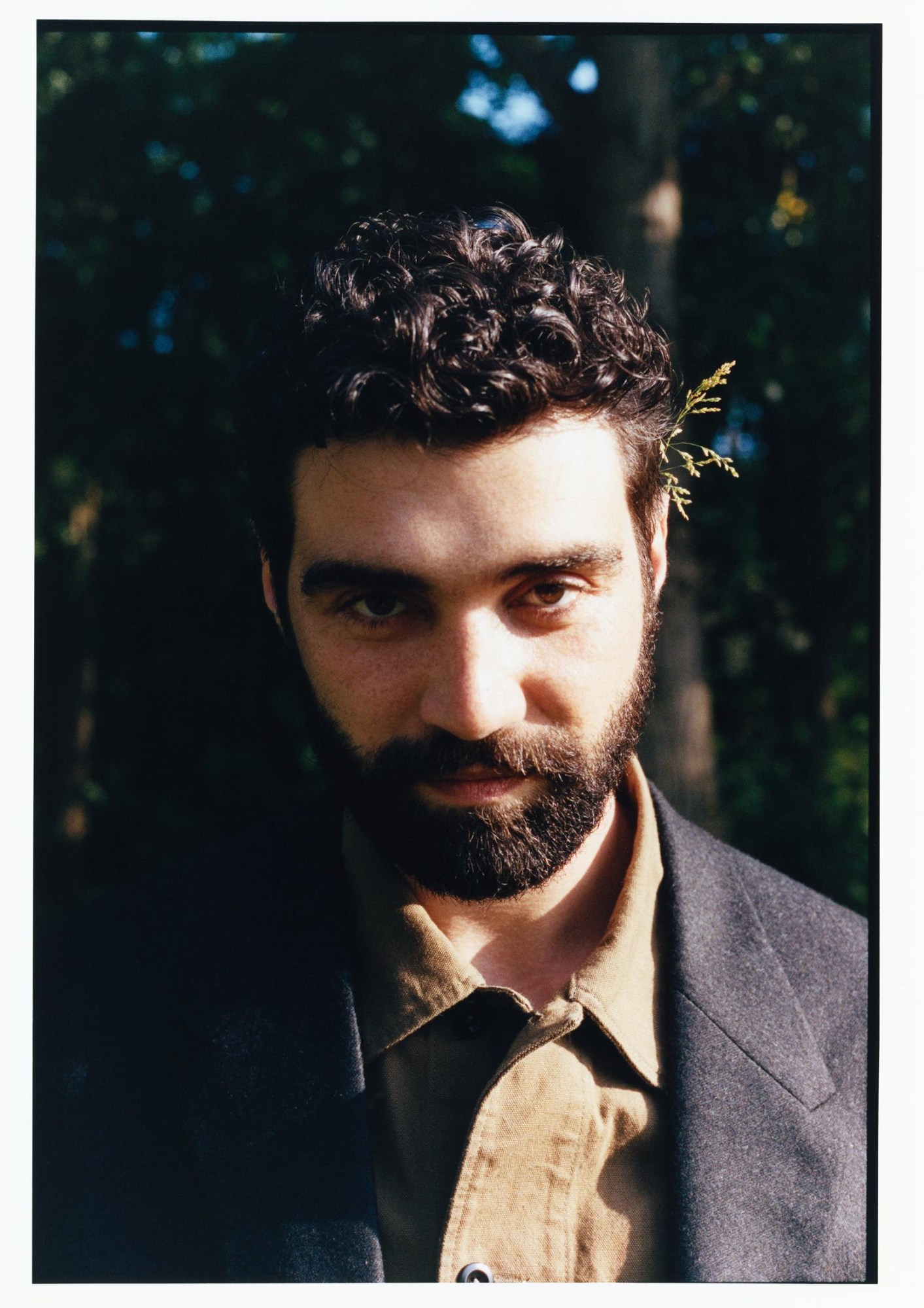

Alec wears jacket and shirt Belstaff. T-shirt stylist’s own.

In God’s Own Country, Gheorghe’s story plays second fiddle to Johnny’s, an apt reflection of the migrant experience. No one asks Gheorghe how he got here or where he’s come from. Yet Alec imbues his performance with a sense of his past, undiscovered. “Gheorghe has developed some survival skills over time because he just wants to work and to be able to survive,” he explains. “That’s why he keeps his head down. Until a point…”

That point being when the two young men are sent to work together during lambing season. Until then, Johnny resents the seasonal worker but an enforced camp out on the hillside with only instant noodles and each other for warmth sees things get a little Brokeback Mountain.They have sex, but not in the self-serving manner Johnny is accustomed to, and their dynamic dramatically changes.

Brokeback comparisons have stuck to God’s Own Country, despite Francis Lee’s film winning awards in its own right at Sundance, Berlin and Edinburgh film festivals this year. But then the film actively invites the observation, since it pays homage to Ang Lee’s gay cowboy romance from 2005 in two key scenes. But, after acknowledging the debt, God’s Own Country moves into different territory. Unlike Brokeback, the young men are not curtailed by homophobia, but other forces. “What’s standing in the way of romance and a relationship for Johnny isn’t necessarily sexuality,” Josh says of his character, “it’s the emotional intelligence to make that work and to allow himself to be vulnerable.”

That distinction does not preclude God’s Own Country from becoming its own addition to the queer canon. On the film festival circuit, the actors have been able to gauge audience reaction to the resolution of Johnny and Gheorghe’s romance. “LGBT people told us that they needed a film like this because it is about hope,” Alec says, mindful of spoiling the film’s conclusion. “Most LGBT films don’t have happy endings, they end tragically, with murder, or death, or AIDS. This gives a sense that things could end up alright.”

Credits

Text Colin Crummy

Photography Clare Shilland

Styling Hanna Kelifa

Grooming Hiroshi Matsushita using Oribe Hair Care. Photography assistance Andy Moores. Styling assistance Pippa Atkinson.