On January 24th 2023, the minute hand of the Doomsday Clock – a symbolic timepiece that indicates the likelihood of human-precipitated apocalypse – moved to 90 seconds to midnight. The shift served as an ominous reminder that we are the closest to global catastrophe we have been since the clock’s inauguration in 1945, in the wake of the dropping of two atomic bombs on Japan. “We are living in a time of unprecedented danger, and the Doomsday Clock time reflects that reality,” said Rachel Bronson, president of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, the clock’s custodians, citing increased nuclear threats from Putin’s Russia over the Ukraine war, global carbon emissions hitting record highs, increased biological threats, and an omnipresent climate of political disinformation. “It’s a decision our experts do not take lightly.”

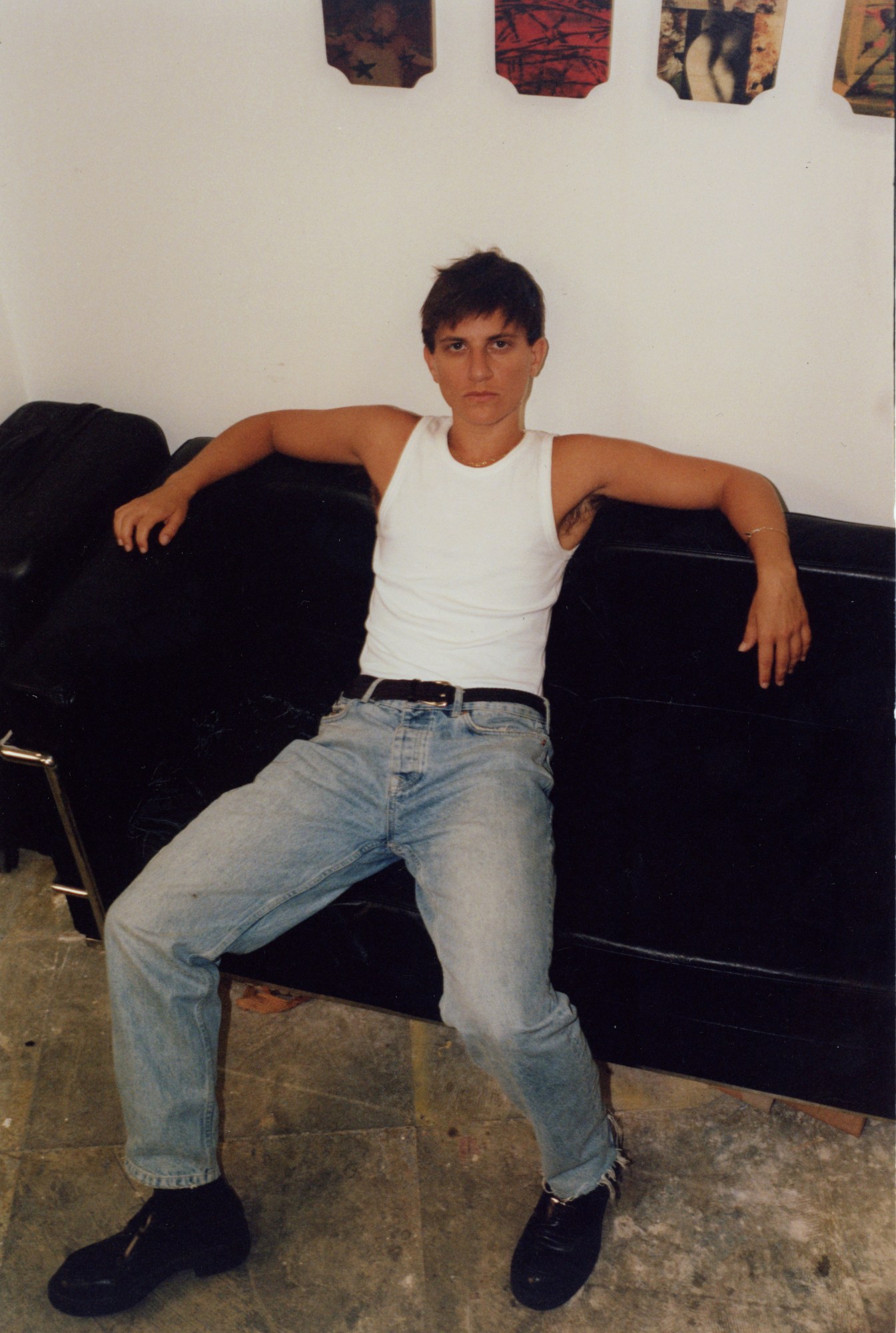

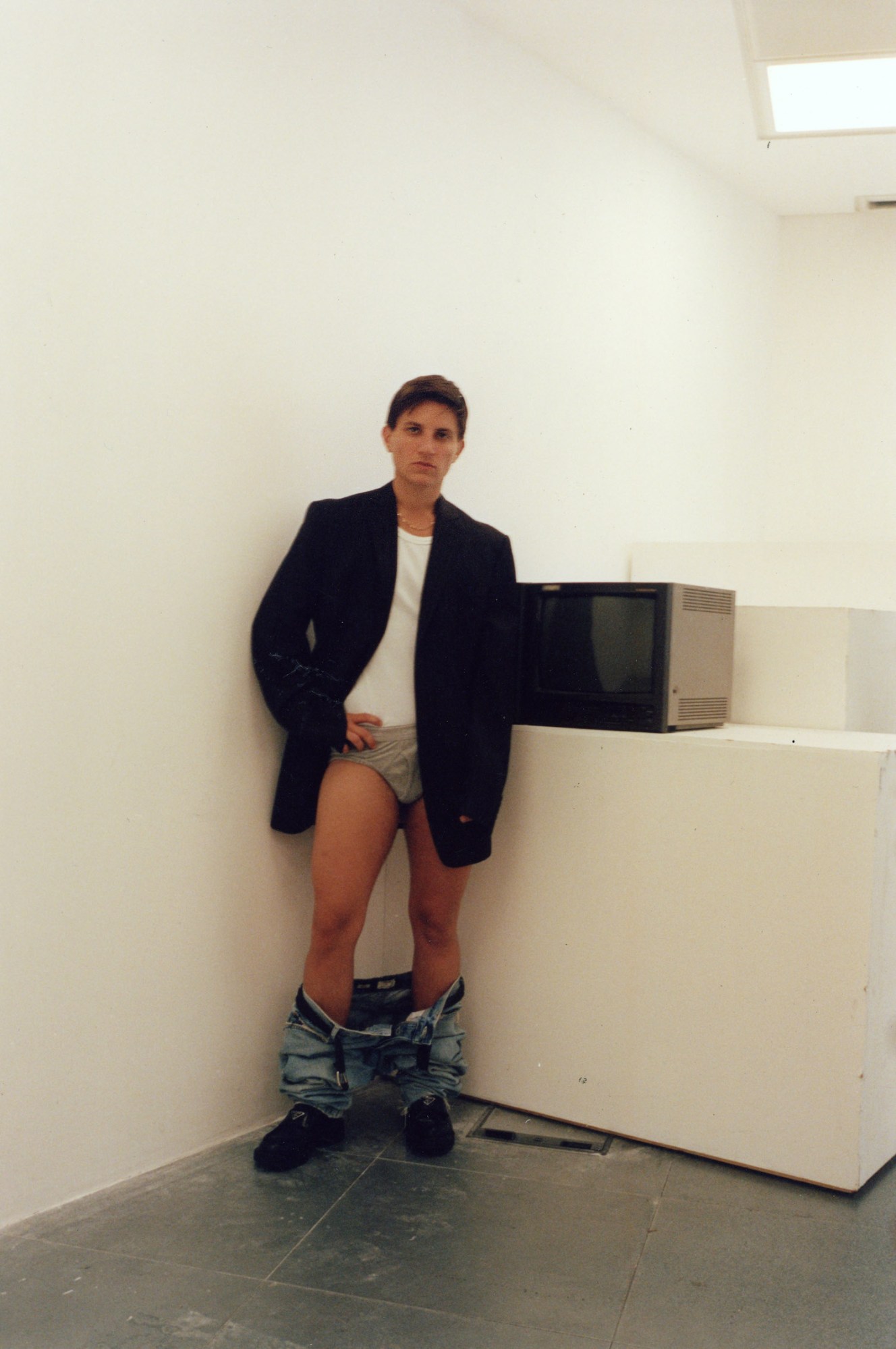

It was around this time that Gray Wielebinski – the LA and London-based artist – began research for his biggest commission to date: a solo exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts; a prestigious London arts institution within touching distance of Buckingham Palace, the royal seat, and Whitehall, the heart of Britain’s political institution. Situated along such a renowned physical axis of power, the ICA’s location became a natural preoccupation for The Red Sun is High, the Blue Low – particularly, the eeriness its immediate context elicits in our current pre-apocalyptic cultural climate; the notion that, metres from where visitors are stood, decisions could be made that could bring about the end of the world.

The conclusions are subjective, but Gray’s interest here is to interrogate the Doomsday Clock’s function as a powerful tool in institutional meaning-making. “It’s a very rich and sensitive affect to plug into. I was thinking about paranoia as a lens to look at power, information, truth and history,” he explains, drawing upon Cold War social science theories, and their deployment by Western governments to recalibrate social dogma in line with specific political motives. “After all, the term itself is a loaded way of implying that someone else’s perspective is biased.”

Rather than outright condemnation of paranoia here, there’s a noteworthy focus on its qualities as a necessary tool for self-preservation, so to speak. “What does it mean to be paranoid with good reason?” Gray asks. “I think that’s how a lot of us feel right now. Ultimately, I’m very invested in investigating the power that’s involved in storytelling, which, with closer investigation, can often slip. Who’s paranoid, or what does it mean to be paranoid? Especially in a time that’s kind of crazy-making.”

Walking into the ICA’s cavernous exhibition space, you’re struck by a curious sense of abstraction; given its prolific location, it’s hard to totally forget where you are – and recent exhibitions. have even included concerted efforts to foster a sense of permeability between the space’s interior and its external surround, with high windows giving onto the immediately adjacent St James’ Park. Here, though, Gray takes the opposite tack. Windows are whitewashed, daubed in swirls of caulk, creating an antagonistic delineation between a protected inner sanctum and the potential harms that lie beyond it — a direct reference to the British government’s futile Cold War-era counsel regarding how to prepare for supposedly imminent nuclear war. Their freeform contours also echo the hectic swirls of Pollock paintings, implicating the notorious tale that “unbeknownst to the artists, during the cold war, the CIA was actually involved in bolstering Abstract Expressionism,” Gray shares, “because it was so starkly in opposition to Socialist Realism from the Soviet Union.”

“It was the pinnacle of American capitalist freedom of expression, and really taps into this idea of the soft power these types of regimes have, and the ways in which beauty can be deployed as a tool of power”, he says.

This playful ambivalence between innocuous surfaces and the sinister meaning they may (or may not) conceal shimmers throughout the show. Throughout the space rings the sound of what could either be cicadas nestled in neighbouring trees or urgent alarm drones. At one end hangs a retro basketball scoreboard, the periodic flicker of its display implying your participation in a game where the rules are unclear, a sense buttressed by the series of shooting target-like prints of concentric circles suspended at the court’s opposite end.

At the show’s centre, you’ll find a conversation-pit-like huddle of chairs, while at the rear, a metal grille door gives way to a dark bunker lined with numerical lockboxes, and outfitted with a peephole that offers a vantage point on the comings and goings of the exhibition’s main space. Through its sequestration, it naturally invites you to contemplate the practices of doomsday preppers – billionaires with nuclear proof safe-rooms and the like – not to mention the widespread rumours of tunnels that run beneath the ICA itself. Reinforced by the presence of the nearby Admirality Citadel, these are designed to safeguard and evacuate the royal family in the event of the outbreak of war.

Beyond that, though, there’s also a broader contemplation of the blurred distinctions between public and private spaces, and how our perceptions of them mediate our behaviour around and within them. It’s a theme that has long figured as a pillar of Gray’s work, notably in a recent installation at Selfridges, Exhibition (2022), an edifice-like sculpture of a public bathroom that invokes their history as cottaging sites – with parallel notions also invoked by the ICA bunker’s status as a literal dark room, and nearby St James’ Park’s former status as a busy cruising ground – and their contemporary status as sites engulfed by culture wars in the wake of propagandised anti-trans bathroom panics.

The exhibition’s broader themes – particularly the notion of phallocentric power structures and their interrogation and subversion – are also recurring themes in Gray’s practice. Among the many notable recent works of his, his cross-shaped frames containing collages of Abercrombie & Fitch shopping bags are standout, while work he’s preparing for upcoming exhibitions at Gió Marconi in Milan and Anat Ebgi in LA include a series of disciplinary paddles that explore notions of parental discipline and “the notion of how desire can subvert power”.

Subscribe to i-D NEWSFLASH. A weekly newsletter delivered to your inbox on Fridays.

“If you like being dominated or punished — or paddled — there’s still a connotation of violence, but there’s a different relationship to it,” he says, as well as psychosexually charged collages that draw their source material from vintage gay porn and frat magazines.

What makes The Red Sun is High, The Blue Low feel more expansive in scope, though, is less its physical scale, and more the zoomed-out abstraction of the power structures in question. This is perhaps most poignantly achieved by the six blurred images of rising suns along the main space’s back wall, each a still from Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 1982 masterpiece Querelle. Just as the film itself conjures a sense of suspended time – of lacking consequence, of life as a desire-driven dérive towards a tomorrow that may never come – the recurring suns introduce an ambivalence around how the exhibition, and the experience of it, is to be contextualised and understood. Are these suns to be interpreted as a film-strip-like series a single setting sun? Or are we in a world with six of them, a reality that would upend our understanding of the world on a fundamental level, physical level?

Of course thoughts themselves are hardly enough to counter gravity, but the intentional act of eliciting them echoes Gray’s readings of the works of Samuel R. Delany – the American science-fiction novelist and essayist, whose work informed the exhibition’s title. “There’s one passage which describes this idea of misperceiving the sun rising and coming through the window as the apocalypse,” Gray says, “and, for those four seconds, there’s a shift between thinking that the world is about to end to being like, ‘Oh, it’s just the sun hitting this way.’.”

In that moment of abstraction, the sun’s status as a cipher for the mundane, predictable continuity of our existence – the thing in the sky that will, inevitably always rise again – is distorted; you almost can’t help but ponder the widely-accepted scientific theories that, if we don’t achieve it by our own hands first, the sun’s rapid expansion is what will ultimately end us – and everything we’ve built. “It’s an incredibly extreme, physically affective way of experiencing, fearing and relating to the world around you,” says Gray. “But also, at the same time, you have to abstract things in the everyday to not constantly be thinking about the fact that we’re always facing our own demise.”

It’s tempting to read that scoreboard, then, as an emblem of a cynical, nihilistic worldview. Sure, there may be rules at hand here, but what do they matter? What point is there in being scared into abiding by them if the structures propping them up are ultimately doomed to disintegrate? Ultimately, The Red Sun is High, the Blue Low neither confirms nor counters such conclusions. It leaves us with a lingering sense of ambivalence that is, arguably, the defining emotional condition of life in our pre-apocalyptic times.

Within that ambivalence, though, as much as there is fear and pessimism, there’s also cause for continued living – if perhaps not hope. “Working on this show has been quite heavy — I’ve definitely been haunting myself and really confronting my thoughts on a lot of the biggest subjects,” Gray says. “I now know that when the apocalypse comes, I’m going down with the ship. But that also makes me feel more alive and connected, too. The act of confronting it has made me realise that what is most important is our relationships and each other. It’s reinvigorated a sense of connectedness.” After all, if we’re going down, better together than alone.

The Red Sun is High, the Blue Low at ICA London until 23 December 2023.