“While the exclusion of women from positions of power in the film and music industry is not new, it has certainly been in the news a lot lately.” Veteran music journalist Evelyn McDonnell has been a fan and a critic of both music and film since chronicling the local rock scene for The New Paper in Providence, Rhode Island. This weekend she’s staging a festival celebrating “the feminist acts of making sound and vision” in Los Angeles along with Sharon Mooney, a fellow professor and filmmaker reared on punk rock and Riot Grrrl. McDonnell and Mooney have assembled an all-star lineup that includes Floria Sigismondi (The Runaways), Penelope Spheeris (The Decline of Western Civilization, Wayne’s World), Lizzie Borden (Born in Flames), and Abby Moser (Grrrl Love and Revolution: Riot Grrrl NYC.)

“Sharon and I wanted to show that there are alternative routes to making and distributing art besides the major-label and studio systems, and to showcase women who have made great works despite the obstacles,” McDonnell tells us. “We want to show girls that you can seize the means of production yourself.” Riot Grrrl might have exploded in the 90s, but the connection between punk and feminism didn’t die when that decade came to a close. “If women don’t tell the story, then female characters get relegated to smaller roles, fewer lines, and stereotypical portrayals.”

We talked to the festival’s OG queens of DIY film — Penelope Spheeris, Floria Sigismondi, Lizzie Borden, and Abby Moser — about the representation of women on screen and the importance of being both seen and heard.

(1983)

Lizzie Borden

There is such a diversity of female perspectives in your film Born in Flames. Do you think that’s something still lacking in mainstream cinema today?

I do. There’s still so much segregation in society, which has come out so sadly this year. The film Tangerine, which I love — people think that Hollywood is a blue city where transgender women are welcome. In West Hollywood, maybe. In Hollywood there’s a murder or a beating of a transgender person every three months. There is so much racial division — no one is speaking the same language. Most Republicans don’t even know how abortion happens. They don’t even know how birth control works.

What were the difficulties you faced making Born in Flames?

The black lesbians in the movie I had to find in bars or playing basketball at the YMCA. In the art world there were maybe three black women and I didn’t even know them. I couldn’t write dialogue for them, I had to hear what they said and then create scripts from improvization. To put words in their mouths would have reduced them to a language, and I think the same thing is happening now. What you see still is white films with black tokens or hispanic tokens. You don’t see real cultural mixes. You only see that cultural exchange in small urban centers.

With regard to your film Working Girls, which tells a day in the life of high-end NYC escorts, do you think society is still afraid of sexual women even though we’re fine with sexualizing them?

Well I have a goddaughter who just turned 16. So much of her sexualization — at least the performance of it — comes from strippers and pornography. I’m totally pro-pornography but I think that we should be able to control the means of production of it. I know a lot of women in the sex industries now who are trying to guide me through exactly what’s necessary for women to have the most power, because I’m putting together a book of stories about strippers.

What are your thoughts on female representation in the industry today?

It’s very narrow minded to talk about the American Academy Awards. If you look at the small film festivals, women are represented. They’re represented all over the world. It’s just that we don’t get to see those films because theaters don’t play them. They’re not going to be even on Netflix. The films are there, they’re just smaller, and they just need to be pushed into the audience’s consciousness. It’s a perspective change.

Penelope Spheeris

How did you experience women’s roles evolving between making the first and third Decline movies?

Well there was a bit of a slump in the middle there, in terms of the position of women. In the punk rock days, from my perspective anyway, it was very liberating. I went through that women’s liberation thing in the late 60s and early 70s, but in the punk rock movement it was kind of different because it was liberating in that you didn’t have to be girly any more. You didn’t have to wear makeup, you could wear combat boots, you could shave your head, you could put a safety pin in your nose, and you didn’t give a shit what you looked like. Then during the second film there was a huge step backwards. The position of women slipped quite badly. I don’t know what the explanation is other than that’s what the guys wanted, and I hate to say it but it appears that’s what the girls wanted too. It was cool to be a groupie back then, and that’s a diminished position.

How do you compare that slump to the position of women now?

It’s better than it was in the early 80s. I think the way women are portrayed in the third Decline movie says a great deal. But to be honest, I don’t think there has been that much progress over the last 100 years for women. It’s a pretty broad statement but that’s the way I feel.

You’ve said that you don’t want comedies such as Wayne’s World to be what people remember you for. Do you think you would have a different perspective if you were a man, because men are less likely to be pigeonholed as directors?

Oh hell yeah, for sure. They don’t give a shit if you’re Steven Spielberg or Oliver Stone or Michael Bay or whoever. Guys can cross genres as much as they want. It’s not that I don’t want to be remembered for Wayne’s World, it’s just that I would prefer to be remembered for the Decline movies. I think they say more. But what the hell difference does it make if you’re remembered for something? You’re dead at that point, so who gives a shit? I’m very gratified that during my alive time people are starting to appreciate my earlier work.

How can the film industry be more welcoming to women?

They’re not going to do it unless they have a gun to their head. So the answer is a gun to their head. And I’m not a violent person. That’s the only way things are going to get pushed even slightly in our direction, is if there’s some legal action. They’re not going to do it out of the kindness of their hearts — whenever you talk about mega-money, mega-glory, mega-fame, mega-ego — the guys just don’t let the women in. But here’s the thing — who wants to do a job because someone was forced to hire you? That’s kind of shitty isn’t it? You want to be hired for your talent and for your resources. You don’t want to be hired because somebody’s going to get sued.

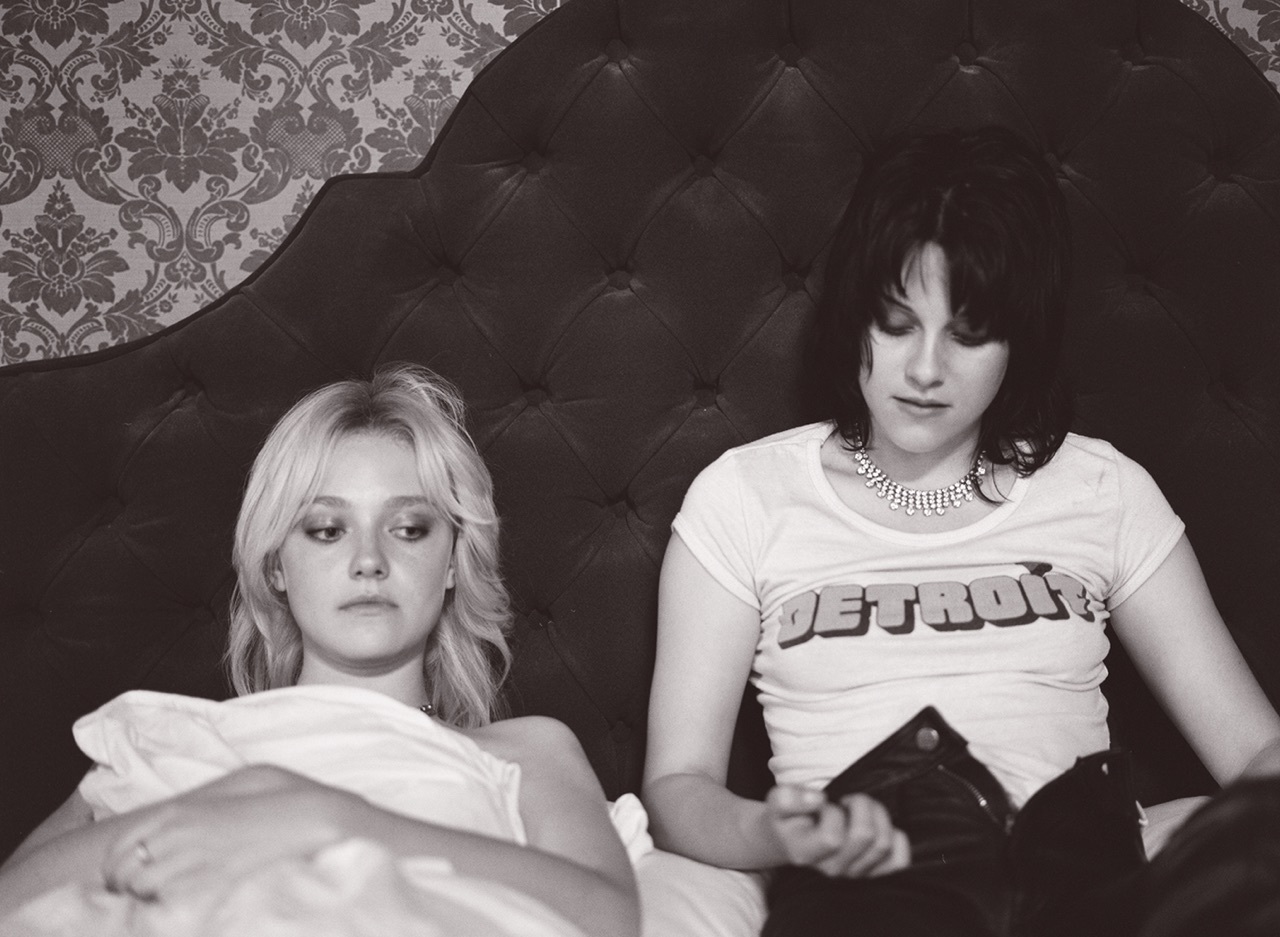

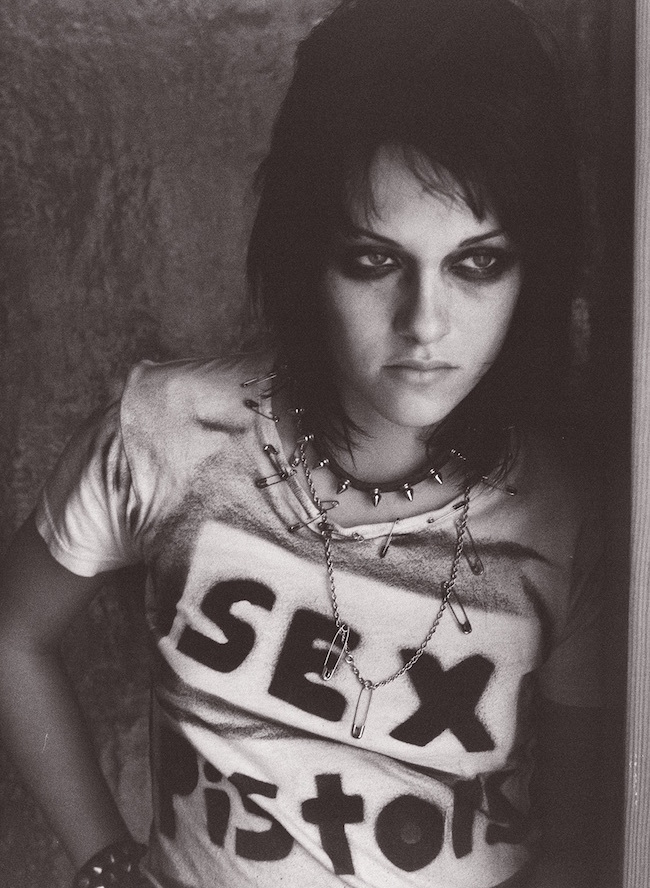

(2010)

Floria Sigismondi

How did fashion photography influence your work as a director?

In the past I was pulling inspiration from designers like McQueen and Westwood. I love their nod to the past infused with a chaotic punk aesthetic. I spent many a late night watching my mother sew garments for her and clients. Both my parents are opera singers so extravagant costumes were always around. Fashion is big part of what I do and is as important as lighting, camera, and music. They are all important parts that make the image whole and inform the mood and tone.

Which films and music videos were crucial to your development as a filmmaker and as a person?

My favorite films were the films of Stanley Kubrick (Clockwork Orange), Roman Polanski (Repulsion, The Tenant), Pasolini (Mamma Roma, Salo), and of course the films of Fellini. These filmmakers created a world so unique that I never wanted the films to end. They transported me and blew my mind.

You worked extensively with David Bowie. In your work as a music video director, what do you look for in an artistic collaborator?

I always want to try new things so I think the best collaborations come from a place of trust and experimentation. The most fruitful collaborations come from a place of mutual respect but also a respect of the creative process.

Why is filmmaking a feminist act?

I think it can be regarded as a feminist act because there is such a small number of women making films. One day when the pendulum lands in a much more balanced place and generations are watching films from both men and women, it won’t seem so rebellious. The biggest challenge as a culture is that all our memories in cinema, the ones that shape our youth, have been made from a male perspective, and that includes women’s memories. The stories need to be more balanced.

What can the filmmaking industry do to upend the male-driven status quo?

The attitude has to change from the men and women funding and green-lighting film projects. Even talking about this seems such an antiquated subject, but sadly we are still here.

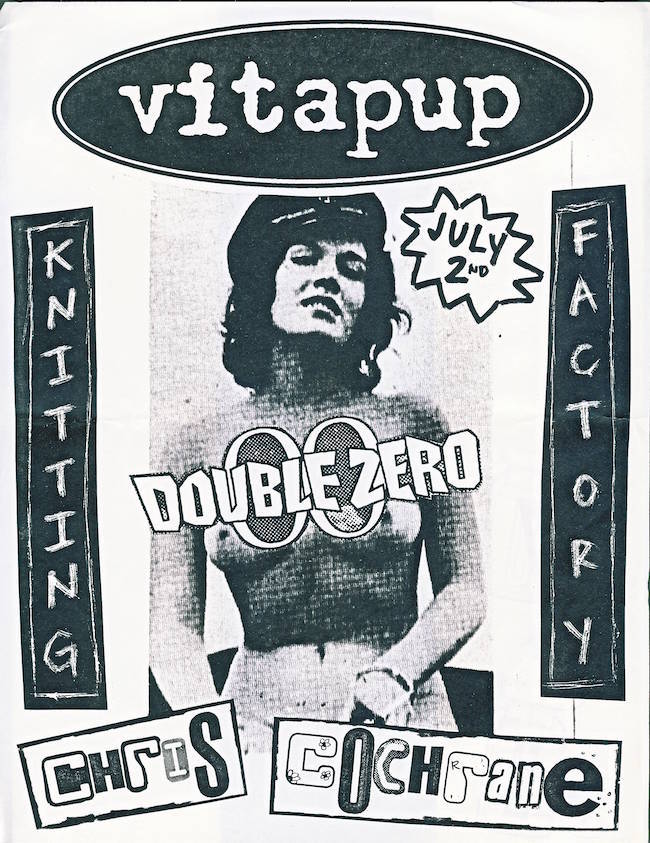

Abby Moser

What similarities do you see between punk music and filmmaking?

I would say there are similarities between the DIY approach to filmmaking and punk rock. I wasn’t intentionally doing DIY to create a punk rock aesthetic, though. I didn’t have a crew or funding so [Grrrl Love and Revolution: Riot Grrrl NYC] was DIY. But in retrospect I can’t imagine going into Riot Grrrl meetings with a crew. It would feel like an invasion of a private space. Jill Reiter from Riot Grrrl NYC told me that girls at the first RG NYC meeting were so shy and lacking in confidence that they were whispering. They literally were finding their voice and a large film crew wouldn’t have helped. Women in Riot Grrrl were both crew members and subjects of the film. Lucy Thane, another filmmaker and I, swapped footage, which is very punk rock. It’s like swapping instruments. Filmmakers don’t generally share their footage this way and are more likely to compete for access to a story. Ours was a punk and feminist/Riot Grrrl inspired approach — collaborating, working with each other.

How important do you think it is that women’s stories be told by other women?

I think it’s important that women make movies, period. By any means necessary. The odds are not in their favor, as Hollywood and indie filmmaking remains a boys club, and a white one at that. I am concerned about young women who feel that they don’t face discrimination. The silver lining for me is that art is an area that can’t be circumscribed and original voices eventually bubble up to the service. But there are also many voices lost in the process, which is why a movement like Riot Grrrl is so important because it provides support and structure that otherwise doesn’t exist. Riot Grrrls made that happen through weekly meetings, putting on shows, creating fanzines. You need to create an environment in which girls and women network with each other. This supportive community comes back to my own film. It was only through the encouragement of a Riot Grrrl member that I learned about and applied for the Sarah Jacobson Film Grant, which allowed me to complete my film. We need to actively create our own networks.

What are your thoughts on the way that women are represented in underground vs. mainstream media?

I think it’s important for women to make their own media — whether it’s underground or mainstream. There are more limits placed on what anyone can do in the mainstream media, which is why underground culture exists. But girls, while doing a lot of work behind the scenes, were marginalized in the underground punk scene as well — being “coat hangers” for their boyfriends’ jackets at shows, to cite just one example, and generally doing much work for little glory. So creating their own girl-centric culture by forming bands, putting on shows, making zines, and doing grassroots political organizing that addressed issues relevant to their lives was a lifeline out of this alienation from the punk scene as well as mainstream society. You don’t realize how starved you are for music that addresses your experience until you hear it. Just listen to Bikini Kill’s “It Feels Blind” (“‘As a woman I was taught to be hungry / Yeah, we could eat just about anything / We’d even eat your hate up like love.’) It captures that feeling of starvation and rage perfectly.

Credits

Text Hannah Ongley