A year or two ago, fashion’s fetish for bootlegging reached such a fever-pitch that large houses took to knocking themselves — and even other bootleggers — off. These achingly meta branding exercises were met with both anger and applause, but, try as they might, the high fashion forays didn’t come close to tapping into the bootleg’s potential as a tool for social discourse. As i-D contributor Anastasiia Fedorova, a London-based writer and curator, explains, bootlegging’s force lies in its ability to “disrupt the social hierarchy of rich and poor, mainstream and underdog. I think a lot of fashion practitioners are attracted to it because it’s playful and subversive — and it has powerful political potential.”

In Seven Sisters, Jon Wright, the man behind Sports Banger, has established himself as the London’s leading contemporary bootlegger. Best known for T-shirts that juxtapose iconic cultural and commercial insignia — a “photo montage of Margaret Thatcher getting clattered ‘round the head at the Battle of Orgreave by police on horseback and the words Ralph Lauren with an upside down Polo logo on the back”, or the NHS logo and a Nike tick below — his work offers open-ended responses to some of the most controversial social situations faced in modern-day Britain. Despite what the actively anti-Conservative leanings that many of his sartorial commentaries might suggest, politics, in an institutional sense, aren’t front-and-centre in his process; instead, you could think of it more as a way of raising two fingers to unjust systems and situations, whatever they may be.

That doesn’t mean that his work can’t be worn to an expressly political end. A version of his recent FUCK BORIS tee was both seen and sold during the recent anti-Brexit protests in London. Most, however, were not the real deal — save for a limited run online, only 300 of the originals were distributed at a Banger-hosted rave during this year’s Glastonbury, along with a single BBC-friendly version that Loyle Carner wore for his performance. And yet, the T-shirt became such a popular rallying call for public ire against the country’s new prime minister that it itself was bootlegged. “You can’t bootleg a bootlegger, people tell me that’s bullshit,” he says when asked for his thoughts on being played at his own game. “I did a run of ‘FUCK BORIS’ T-shirts recently. I was so happy to see the back of them I told people to print their own. I didn’t expect to see people selling them at the Fuck Boris march but someone has to.”

Though his reaction to this low-level copycat behaviour may seem relatively sympathetic, his take on higher-brow brands looking to make a quick buck by bootlegging is less so: “You bootleg because you have to, not because it’s cool,” he says. “Brands have the facilities to make great shit. Make some great shit. I started at the bottom, still at the bottom. Don’t drag yourself down to my level. I’ll crawl in through the cat flap.” It’s this spirit of antipathy towards capitalising institutions, whether governments or Gucci, that underscores Sports Banger’s defiance. It goes some way to explain the reason why, in spite of “five letters from the government identity team, three shut down PayPal accounts, two shut down Big Cartel accounts and one merchant account closed,” he keeps going.

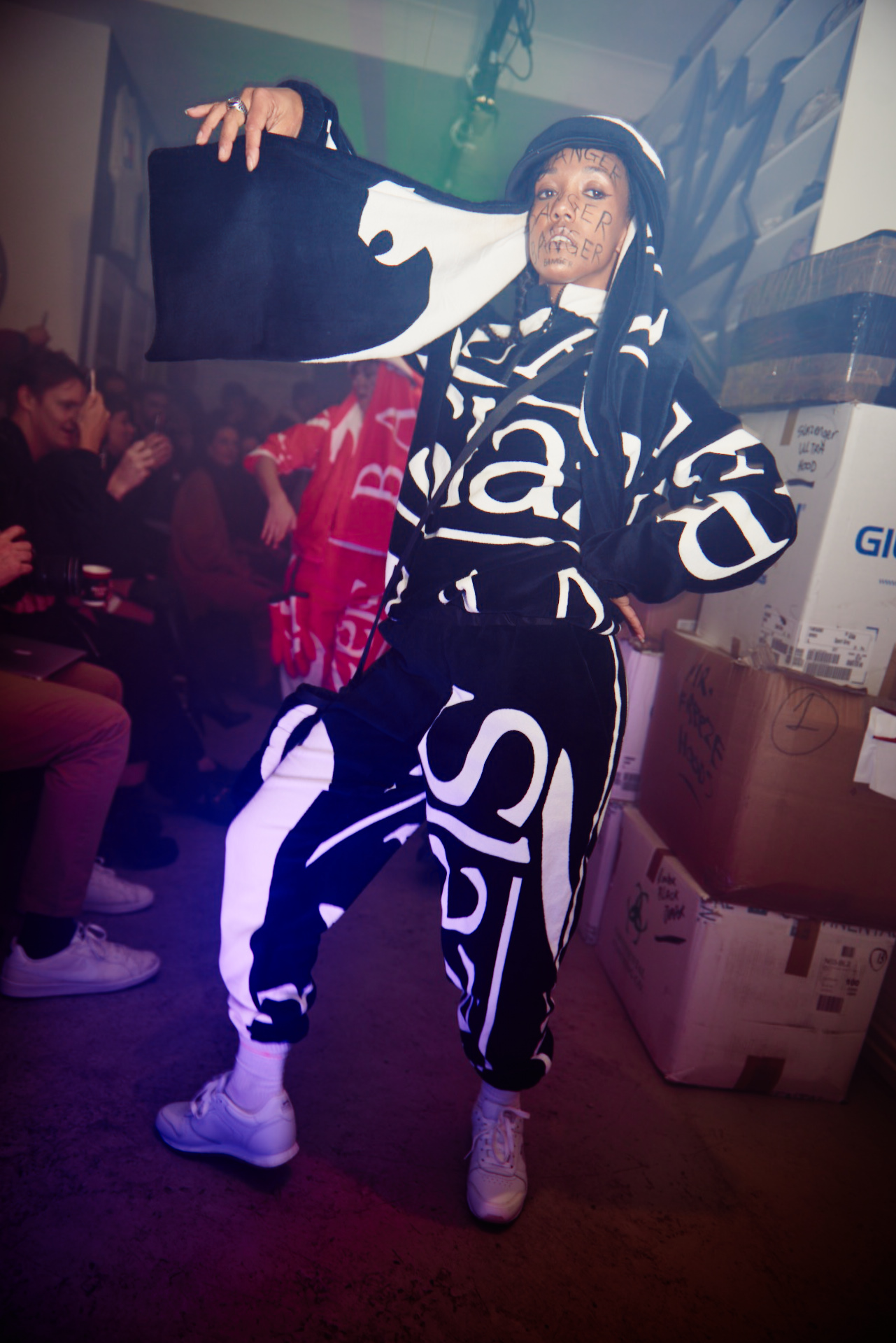

There’s also the fact that Sports Banger’s roots are in rave, something that shines through with Slazenger Banger, a bona fide collaboration with the heritage tennis brand. The line’s extensive product range — it covers printed tees, crop-tops and unisex boxers with an extended front pocket intended to “keep ravers safe”, as well as neon champagne flutes, money pots and lilos — is sold via retailers including sportsdirect.com at prices few would baulk at. While it may seem an unexpected move for a designer with buzz about them, the decision rebuffs the industry standard for jacking up prices for collab products in favour of a ‘for the many, not the few’ approach. There was also his intimate off-schedule autumn/winter 19 show, which saw a load of editors leave Zone 1 for Jon’s Tottenham base and witness a collection that featured giant Mitsubishi logo pingers, bombers repurposed from the aforementioned lilos with the help of Ancuta Sarca, and no shortage of neon. It was a bootleg of a fashion show. Rather than suck up to the fashion system, Sports Banger adopted its vocabulary and translated into its own language.

Given that our everyday lives are held in the vice-like grip of branded powers, tampering with their logos would seem a natural way to speak of the circumstances they perpetuate. But the bootleg’s potential for commentary isn’t limited to more global situations: it also allows insights into the complexities of personal identity. For Anastasiia, whose relationship to bootlegging stems from her youth “in 90s Russia, which was flooded with counterfeit branded goods sold at markets,” bootlegs fulfil both functions simultaneously. Brands “are so prevalent in our lives these days that it’s important not to take them for granted, to keep critical distance and remember that these symbols can and should be questioned, subverted and appropriated – and that anyone could do so,” she says. In a forthcoming exhibition at London’s Fashion Space Gallery, she explores the work of artists and designers using bootlegs as instruments for active political disruption. “A good example is pioneering work of Dr Noki who addresses brand obsession and addiction of consumption through his beautiful handcrafted pieces – and has been doing so since the 90s,” she explains, “or Palestinian designer Shurki Lawrence whose bootleg designs dismantle stereotypes of the Middle East. Or Hypepeace who use the vehicle of streetwear hype to raise money for refugees.” Still, she recognises the medium’s usefulness as a tool for self-examination, noting the “garish Versace jeans and Gucci belts that were my first memories of fashion,” and “how commercial branding penetrates all the spheres of our lives, including private memories and feelings.”

Tin Nguyen and Daniel Chew, the New York-based designers behind CFGNY — Concept Foreign Garments New York — work in a similar register. In a city with a well known reputation for bootlegging, from Dapper Dan’s Harlem atelier to the ‘LV’ handbag vendors along Canal Street, the pair use the genre to explore the “intersection of fashion, race, identity and sexuality”, continually returning to the self-elaborated concept of ‘Vaguely Asian’. Intentionally tricky to define, it challenges Asian-American stereotypes, and founds a new creative, identitarian territory based on the exploration of the cultural mistranslations of symbols and expectations between East and West.

In their earlier work, the pair take to bootlegging to question notions of originality, newness and authenticity in fashion, as well as the extent to which cultural perceptions of fashion production are affected by race. In April 2018, they presented, New Fashion II, a collection that effectively appropriated the design processes of large houses – specifically revisiting and drawing upon archival material – as a means to produce new work. Garments openly referenced landmark moments of fashion history: for example Comme des Garcons’s spring/summer 97 collection ‘Dress Meets Body, Body Meets Dress’ was nodded to with brightly hued mesh tops and dresses with tumorous lumps, the original padding subbed out for plush Pokemon toys.

“We were interested in blurring the line between what it means to engage in ‘authentic’ fashion production and what it means to bootleg,” the pair tells i-D. “The fashion world works on copying and appropriating, it just depends on who is doing the copying that renders something as being authentic or a bootleg. In the past, the role of the original artistic voice is almost always associated with the West, while anything coming out of anywhere else is always suspiciously looked at as somehow trying to emulate what is coming out of the West.”

In effect, this bootlegging practice exposes the hypocrisy of an industry that has long relied on the clandestine ‘borrowing‘ of others’ cultural signifiers, while remaining able to pass itself off as certifiably ‘real‘. At the same time, it doesn’t chastise this process: it celebrates it as a way to push creativity beyond the dictatorial guidelines of what is real or fake: “Instead of considering bootlegging as something as being misused, we like to think of it as a new use and the result of a creative gesture,” says the pair.

CFGNY’s most recent collection, Surface Trend, presented in a park at the edge of Manhattan’s Chinatown, refines their investigation of the nuances of identity: “After doing the project specifically about bootlegs we have explored other ideas, but that is not to say that the language and ideas about bootlegs are not still embedded in our practice, albeit more as a sensibility.” This has seen them move away from the replication of previous design processes, opting instead to work with ‘bootleg parts rather than names’—fabrics from deconstructed knock-off North Face jackets, or panels of laminated Pokémon cards, for example. The result further complicates and pluralises ‘Vaguely Asian’ identity, presenting a bricolage of motifs that feels familiar, but is ultimately impossible to place.

While Sports Banger and CFGNY may adopt different approaches to bootlegging for different purposes, they share common ground in their ability to find a sense of “beauty in the illicit” and “the mistranslation of an imagined aspirational object and the unexpected product that comes from it,” as Tin and Daniel put it. In refusing and subverting traditional ideas of ‘authenticity’, they end up much closer to it than any ‘legit’ brand could hope for.