We meet uptown, on 125th and Martin Luther King Drive. Hak’s “uptown” is way uptown, Harlem. Or “Hahr-lum,” as the rising producer and lyricist says, dawdling over the syllables. “It even sounds elegant, right? Uptown is about elegance.” Hak looks elegant himself, in an olive jacket over a black T-shirt, his leonine features scattered with freckles and framed by wild curls.

Hak, formerly of the obsessively followed hip-hop trio Ratking, compliments me on my Converse, so holey and beat up that he thinks they looked like art. This is Hak. He cherishes the random encounters with beauty that help us understand our world. “Check that out,” he says, pointing to a silver-haired man in velour track pants, and later, the kicks on someone’s dad.

His debut album June, which drops today (in June, appropriately), is a long step from the poetic grime of Ratking. Both as a solo artist and as part of Ratking, Hak’s music boxes up boyhood for broader consumption. But if Ratking was like the Q train from Queens to Brooklyn, gritty and set to the cacophony of survival — shouts, sirens, and sucker punches — then June draws on uptown, on memories of benders in Copenhagen, his mother’s arms, sledding in Central Park, the girls he knew. Hak’s album is uptown because he is uptown.

No one knows exactly why Hak left Ratking, and the internet is buzzing with questions. So I ask what happened. Hak avoids a clear answer: “Too many cooks in the kitchen and too many men. I need balance.” Hak admits he’s a “rowdy boy,” a troublemaker. But that explanation doesn’t make sense to me. Hak’s a poet. And he was moving in a different direction than his bandmates. A year after 700fill, Ratking’s most recent EP, Hak is a coveted image of cool. Multiple brands have asked him to star in, style, and shoot their campaigns. (Under Ratking’s Youtube videos, amid all the praise for Ratking’s musical stylings, is the occasional comment “Hak’s hot.”)

Leaving Ratking meant a change in lifestyle, which Hak welcomed. But it was hard. For years these guys were his days and they experienced the world together. While Hak says, “fame is illusory” and “dollars burn but dreams don’t,” he still walked out on most boys’ fantasies: New York magazine called him “the future of New York hip-hop.”

It boils down to “it didn’t feel right.” After rolling around the world with his clique of rabble-rousers, Hak needed air and space. “It’s all love that I project towards them, but I just felt like I wasn’t being treated nicely to keep it in a hunnid, they didn’t see me for me.” Hak’s dreams are different from theirs. During our day uptown, he vibrates while picking out his favorite scene in Beyoncé’s Lemonade, “where the bedroom is submerged in water.” He loves the beauty of it, the blend of two seemingly separate mediums, art and music.

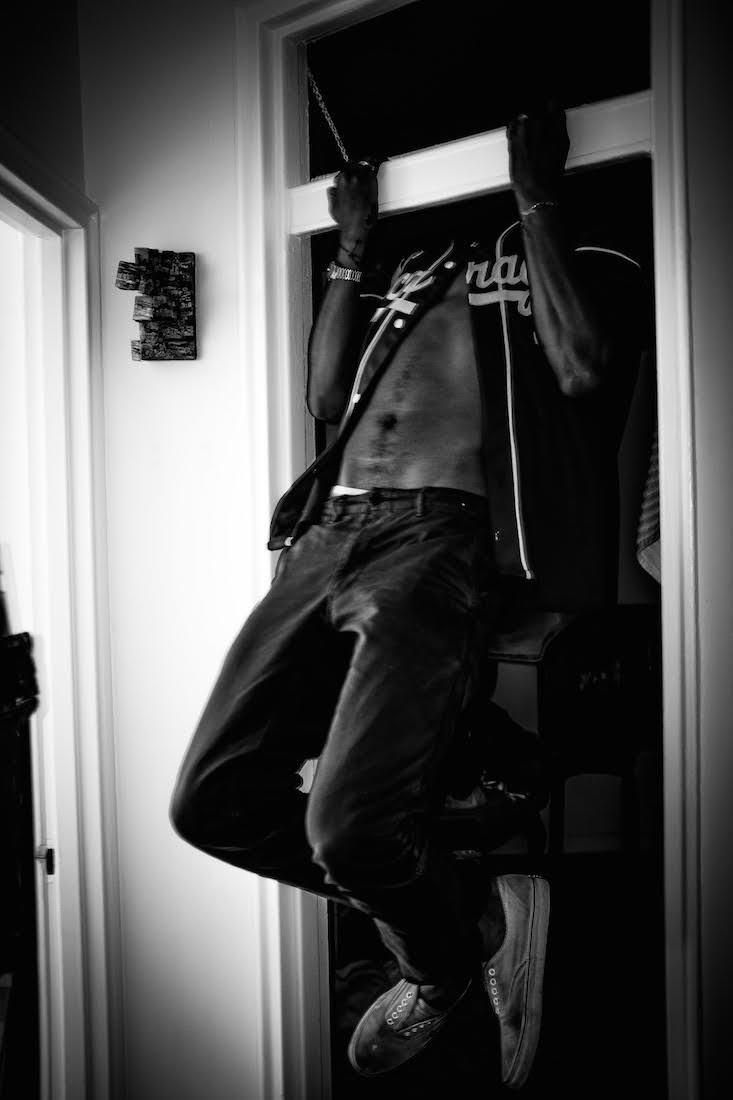

Hak lives in Harlem, on 125th and Lenox, with his parents. For a while after school he bounced around, looking for “strategically frugal” rents in communities of rising artists in Brooklyn. But now, he’s back home. “I always make a point of eating something a little after I wake up, after I’ve moved around, anything involving açaí,” he says. His new life with his family steadies him and gives him the ability to explore as an artist. June is a “summer album,” according to Hak. “You know that feeling of your foot in a sweaty shoe with the moistness rolling around? That’s it.” “Aura,” his first video for the new album, illustrates with a faded palette the point in each summer when the heat begins to suffocate. Hak’s place has no air conditioning, he says. Living under this heat was his metaphor for the obstacles he has to confront as an artist. “This album’s about solitude… self worth. It’s about an artist’s endurance.”

Hak proudly tells me more than once that he’s black and Italian, the biological blend of two communities locked in a fight over few resources: mostly, blue-collar jobs. “Is it common,” I ask, “to be black and Italian?” Hak’s eyes widen, “NO! They hate each other.”

If his parents were able to bridge the gap between rival communities, then there’s a way to connect the awesomeness of the Mona Lisa and Prince. “Sometimes I start with the visual.” For each track on June, Hak asked a friend to submit a work of art which he tapped into while making the music. This sort of intimacy wasn’t possible as part of a band. He made the album sitting cross-legged in his childhood home, clutching his friends’ photos and connecting them to the sounds that surrounded him: the bleeps of Pacman dying, jangling coins, school bells, skate decks riding rails. All this city noise is layered into the music, responding to the call of the vocals, provided mostly by Hak himself. The positioning of sounds harks back to the gospel music and hymns Hak sang as a kid in church. It makes sense; June chronicles his spiritual journey.

Later in the afternoon, Hak points to the Studio Museum. “I’m getting a residency there,” he says. “There” is the epicenter of African-American art, and its residency is where the next Kehinde Wileys and Kara Walkers study the greatness of Jacob Lawrence and Matisse while learning their own forms, readying to launch themselves in the art world. Besides being a lyricist and producer, Hak is a stellar draftsman and painter who’s studied visual art for most of his life. At the Studio, Hak will fit in perfectly.

Hak fits in most places. He’s a pair of fists ready to tackle all sorts of creative endeavors, from lit spits and ad campaigns to capturing the hustle and grace of hood-life with oil paint. And more, probably a lot more.

Credits

Text Kristin Huggins

Photography Anthony Deeing